- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

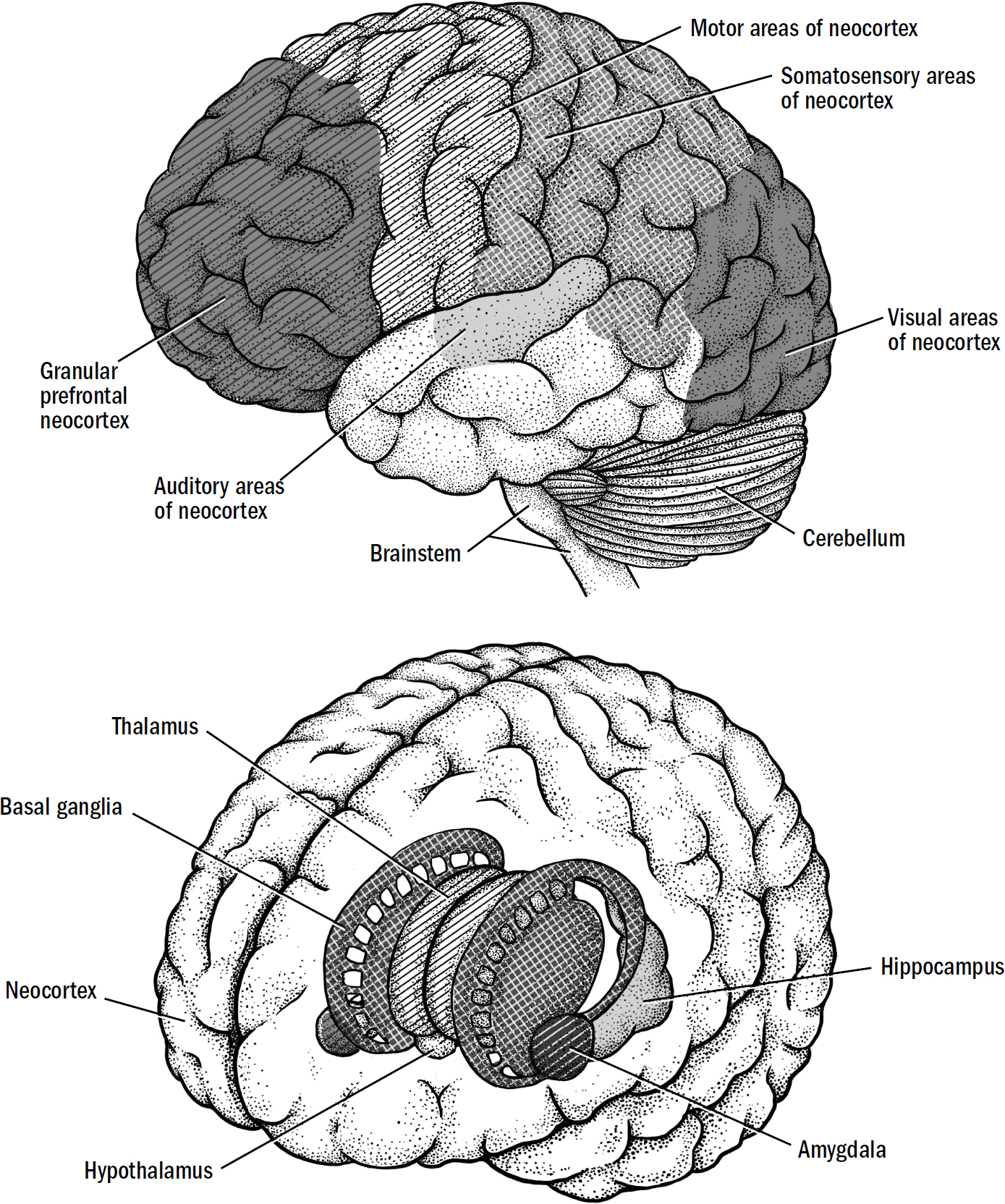

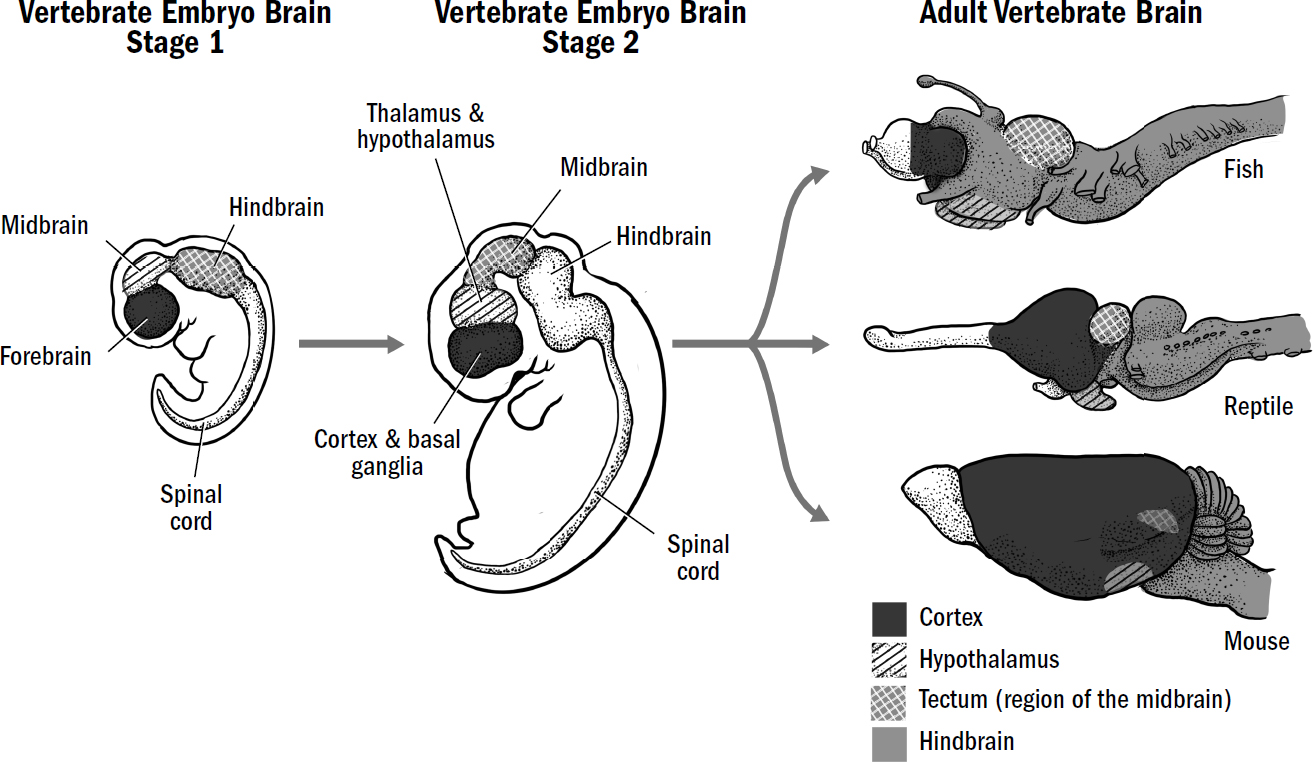

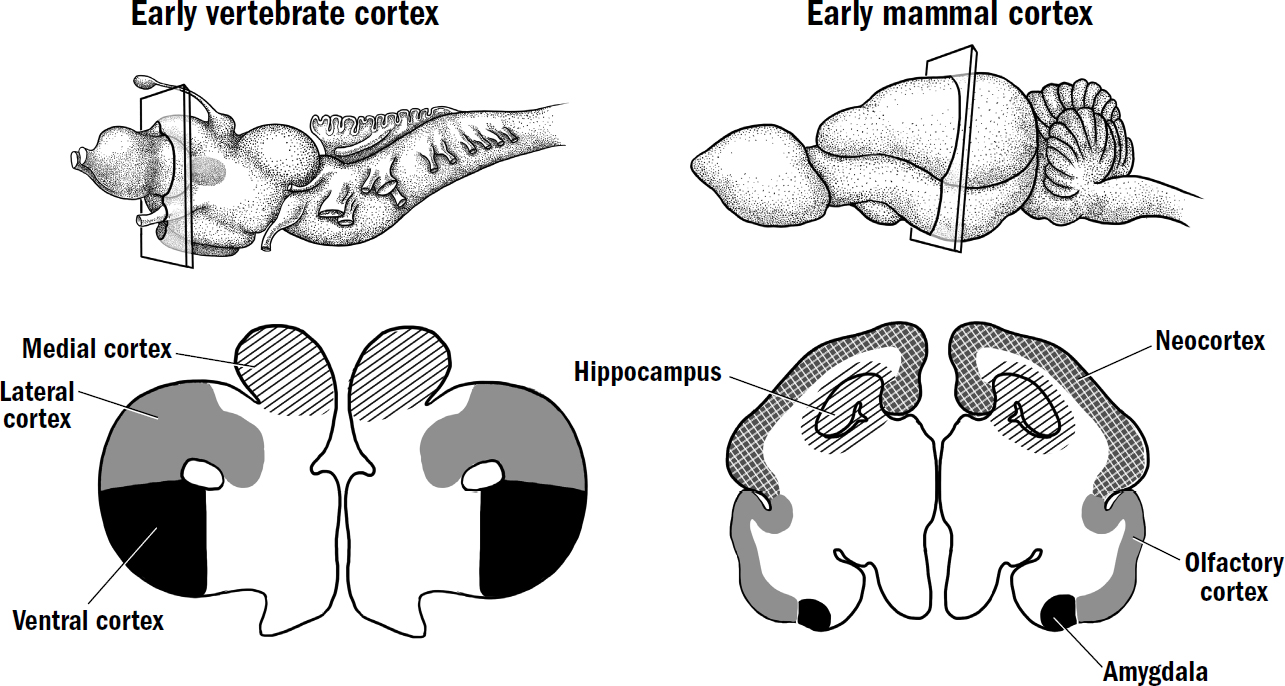

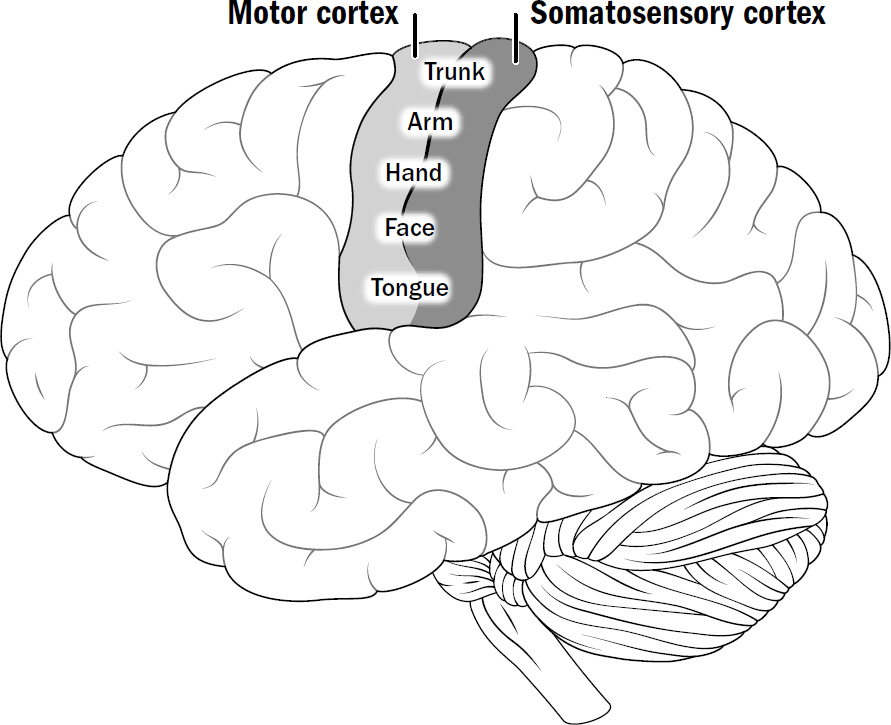

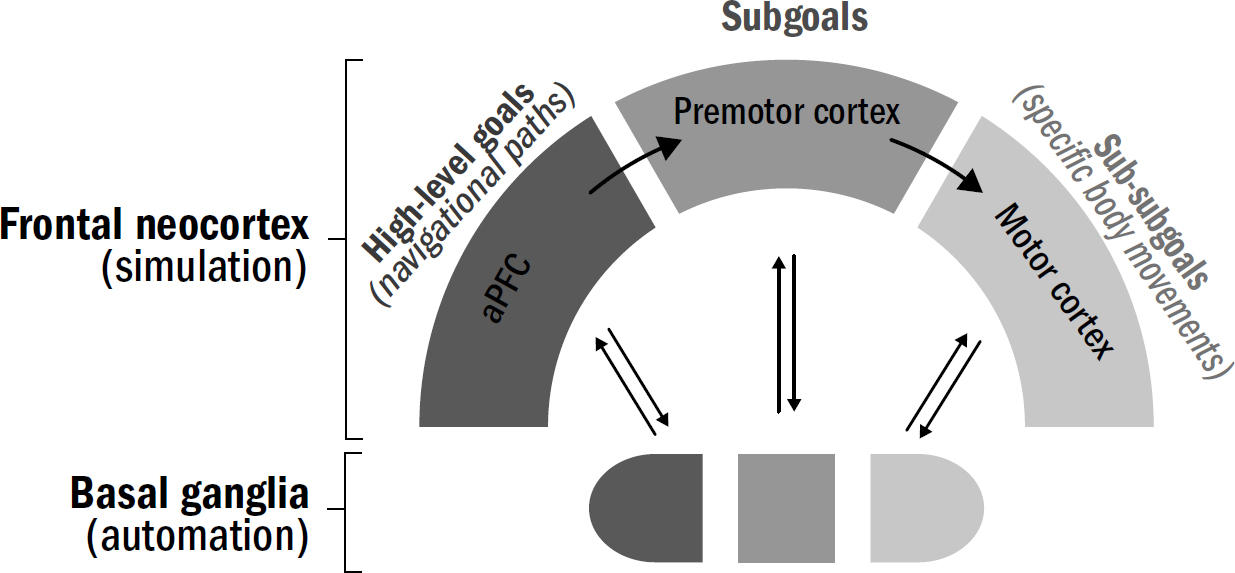

- The Basics of Human Brain Anatomy

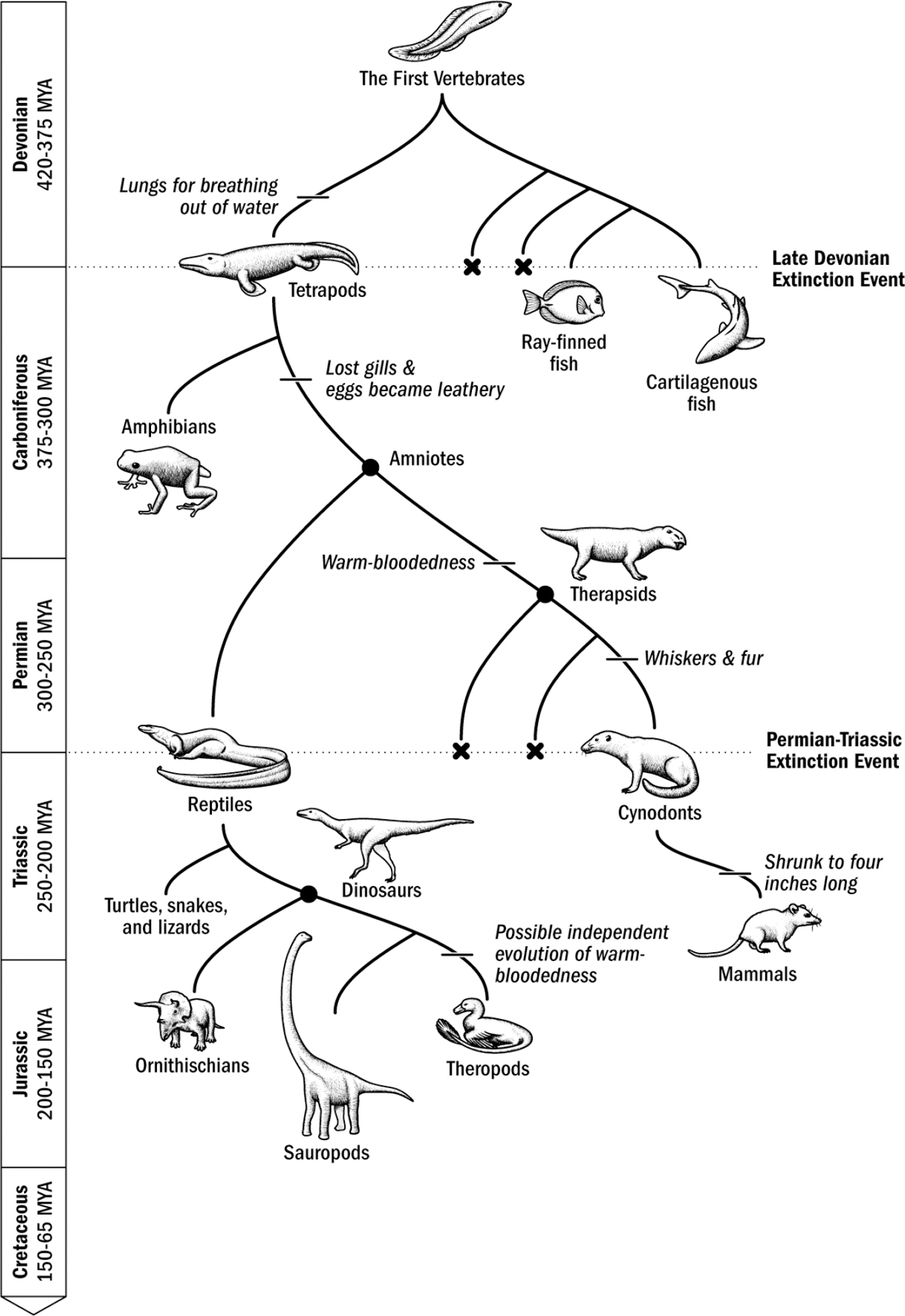

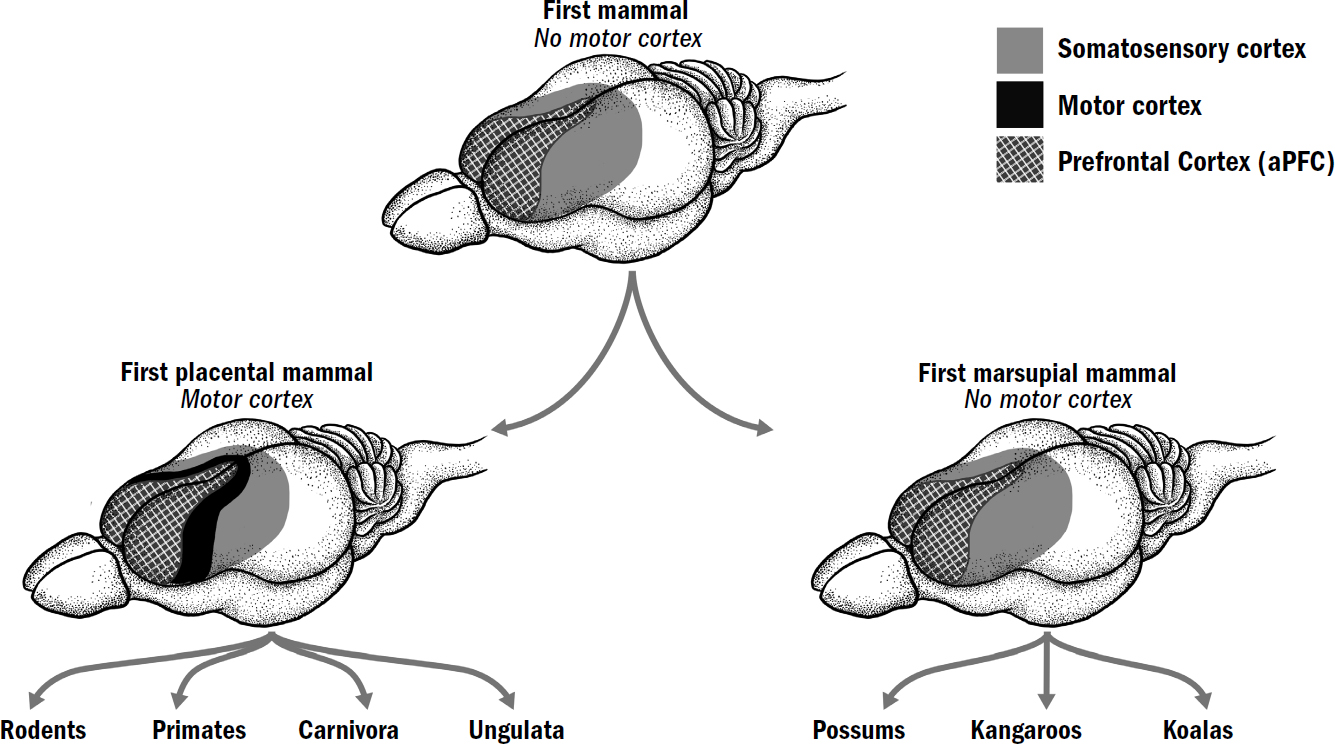

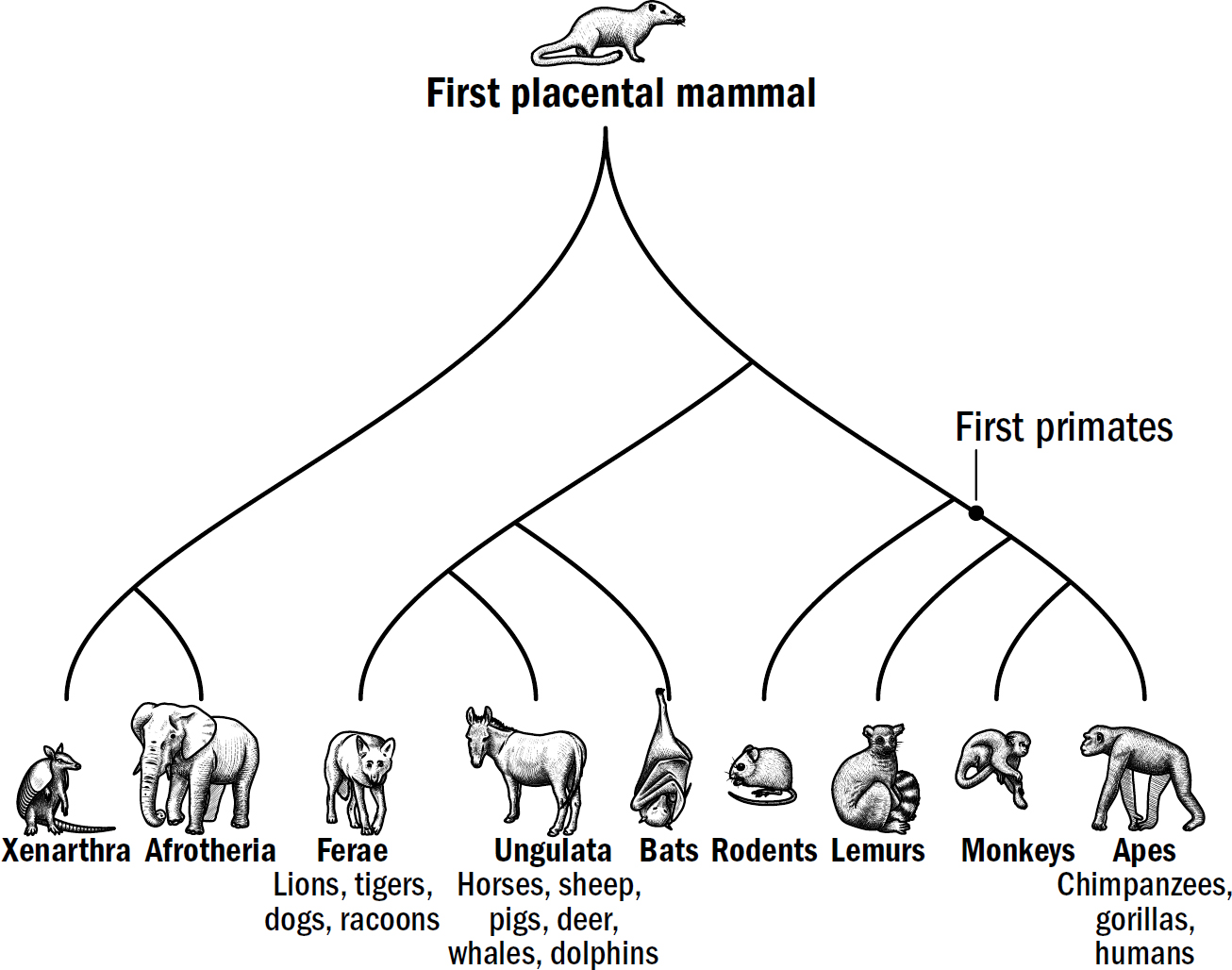

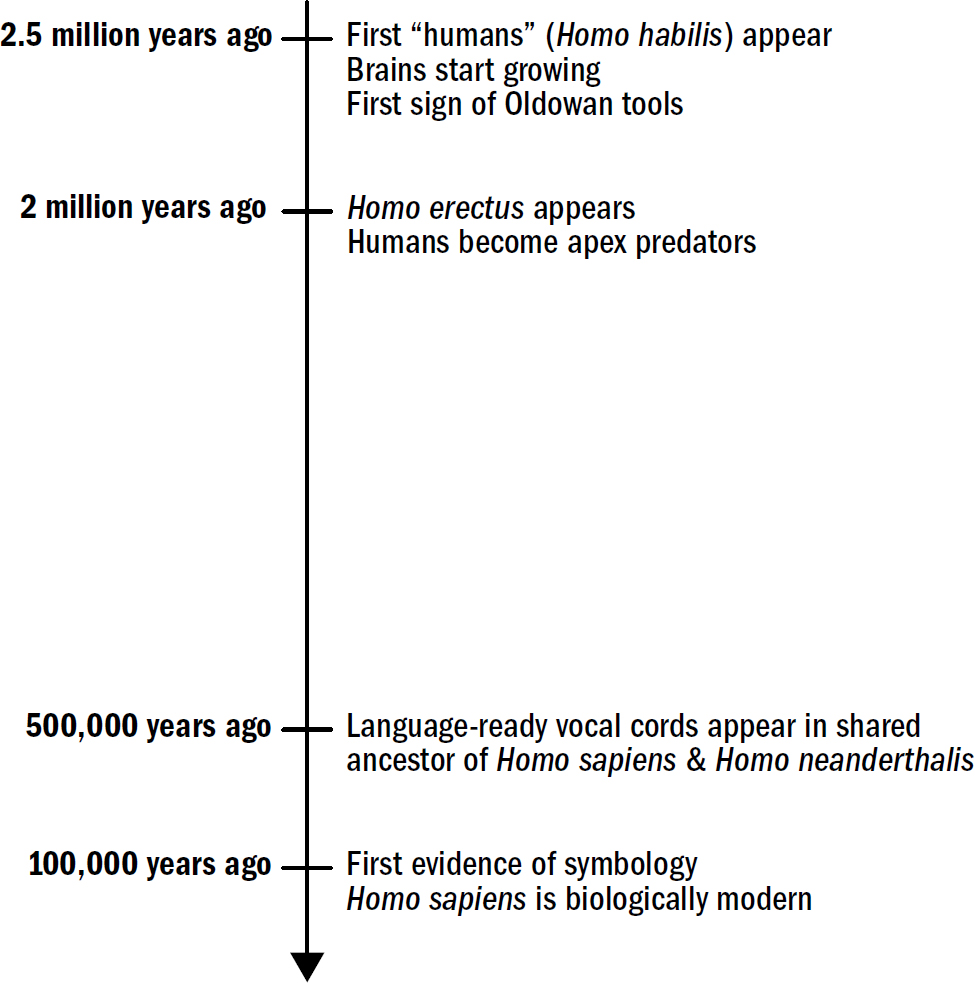

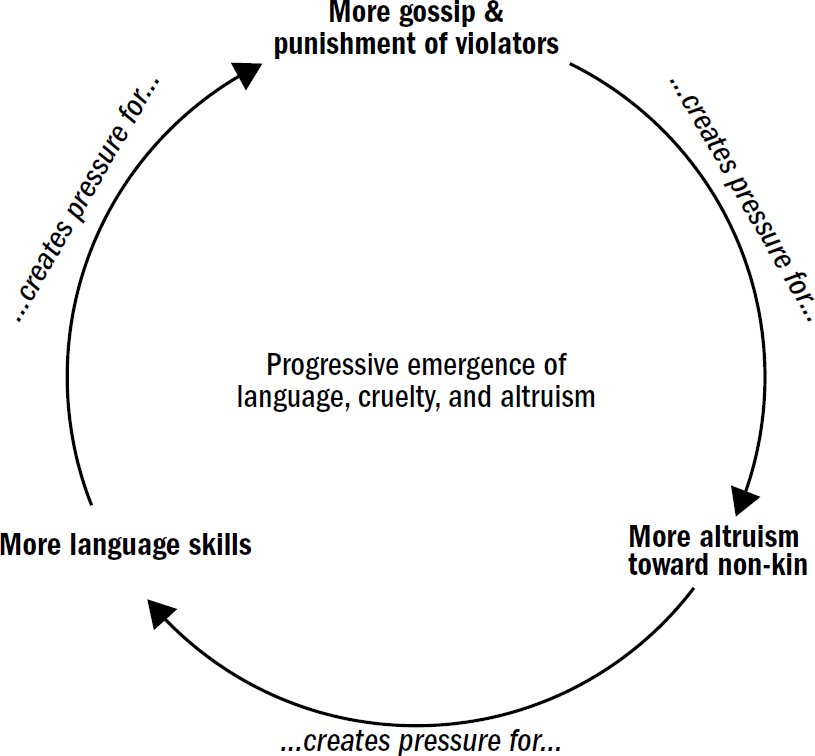

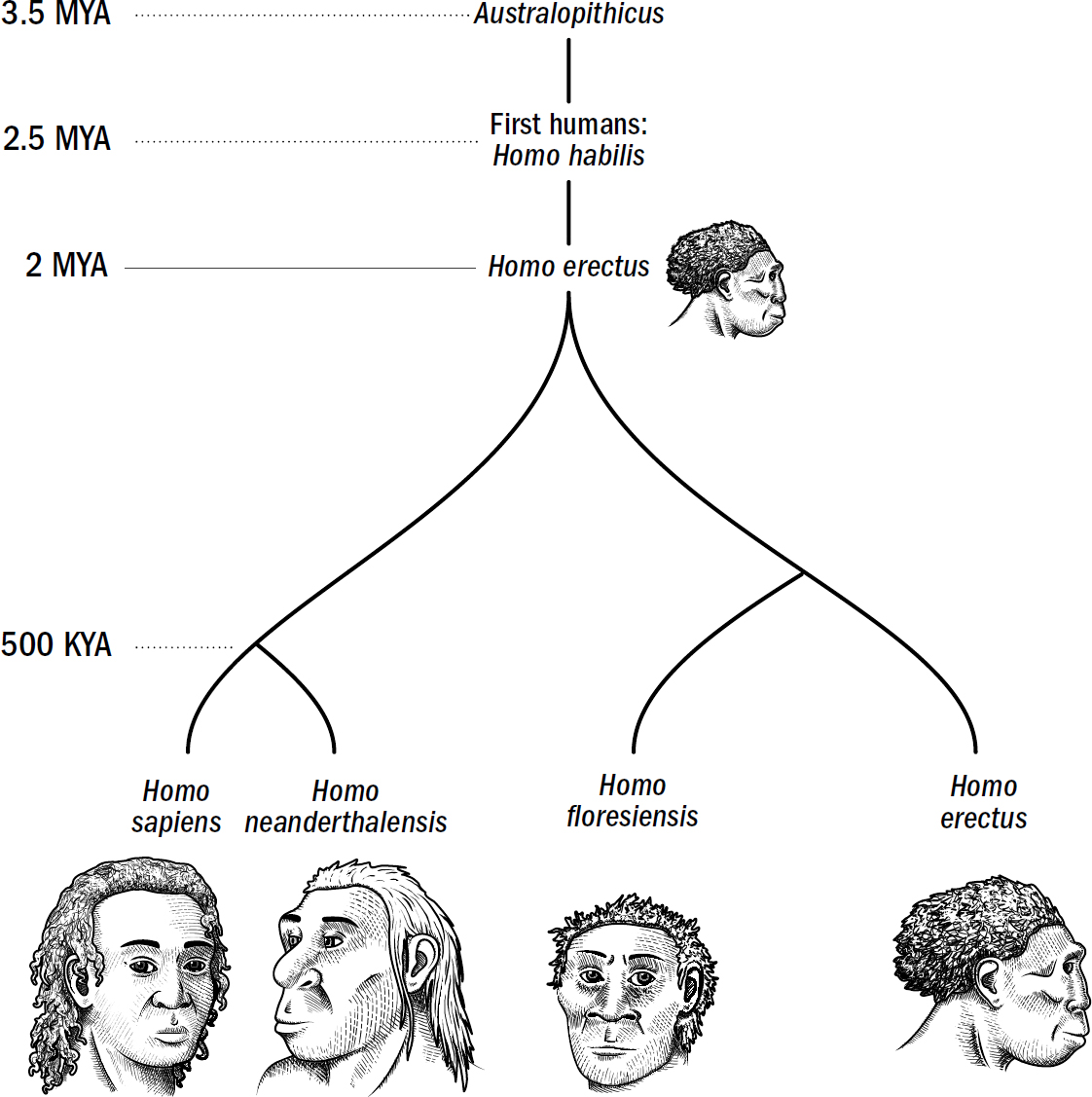

- Our Evolutionary Lineage

- Introduction

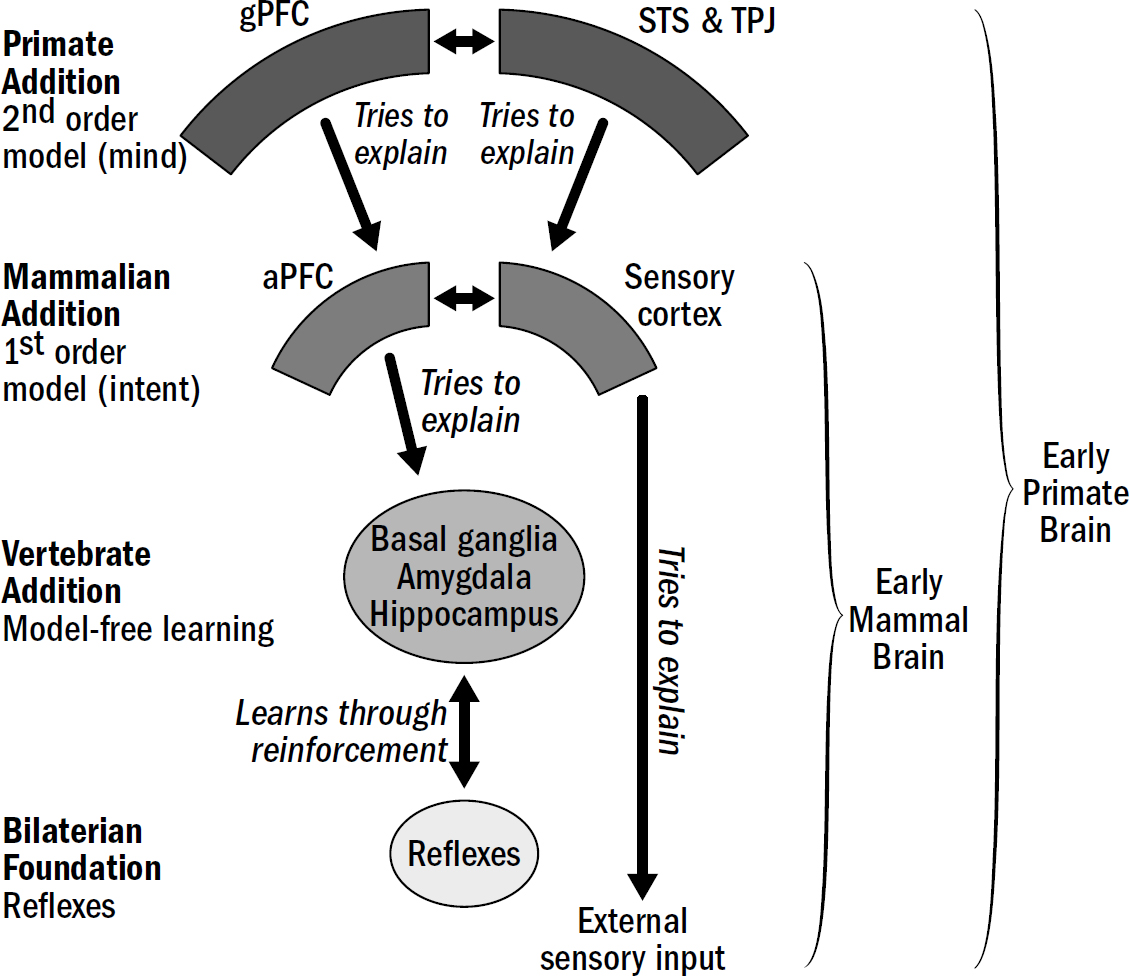

- 1: The World Before Brains

- Breakthrough #1: Steering and the First Bilaterians

- Breakthrough #2: Reinforcing and the First Vertebrates

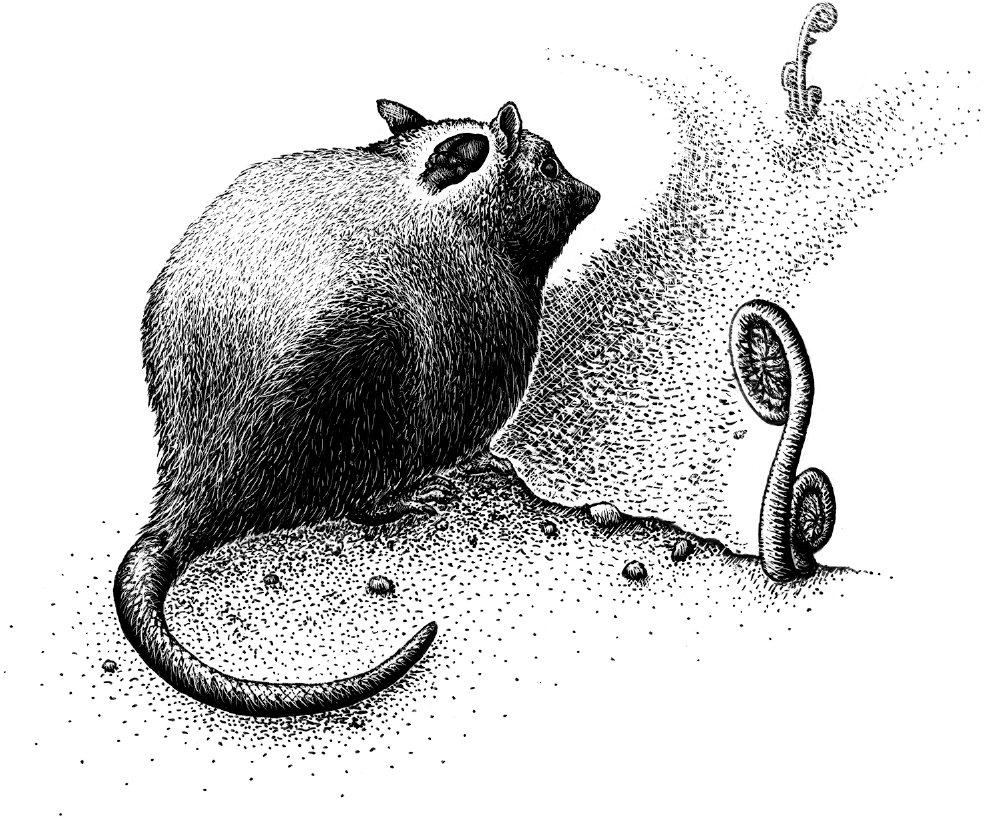

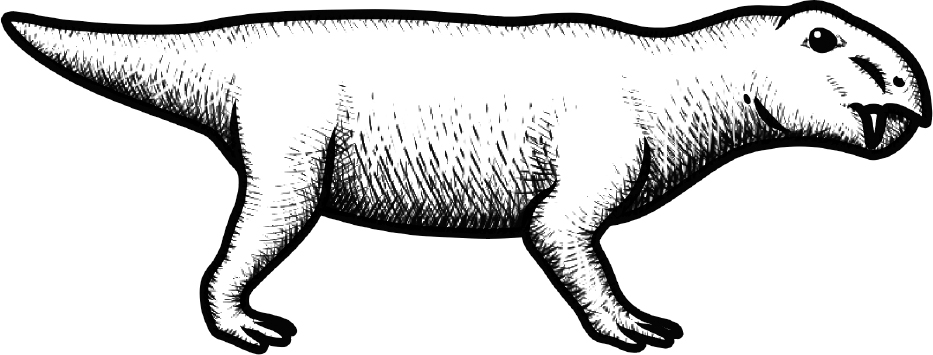

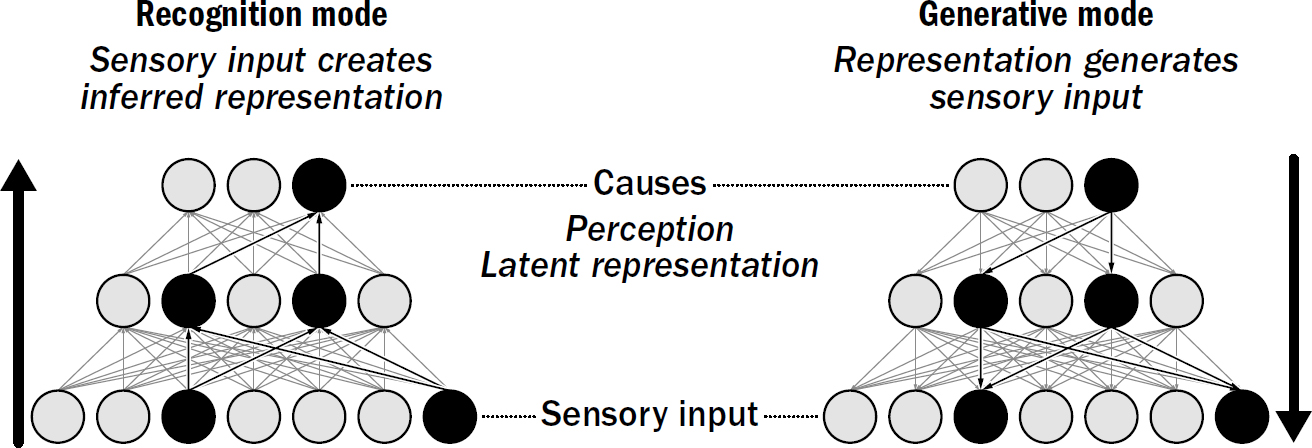

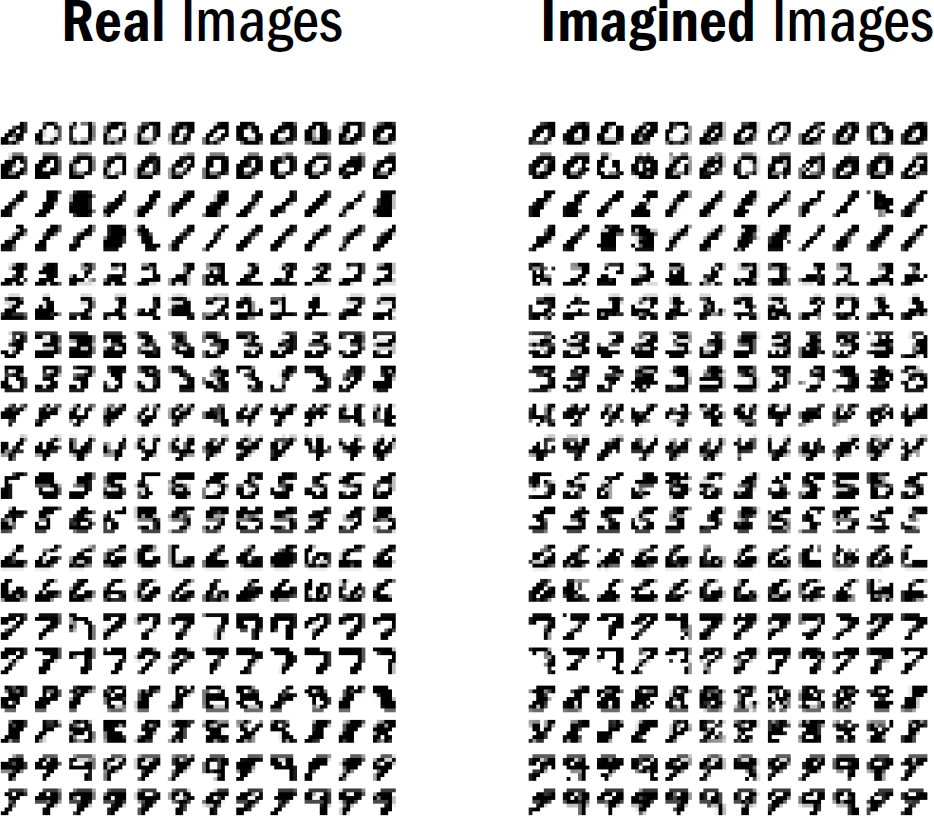

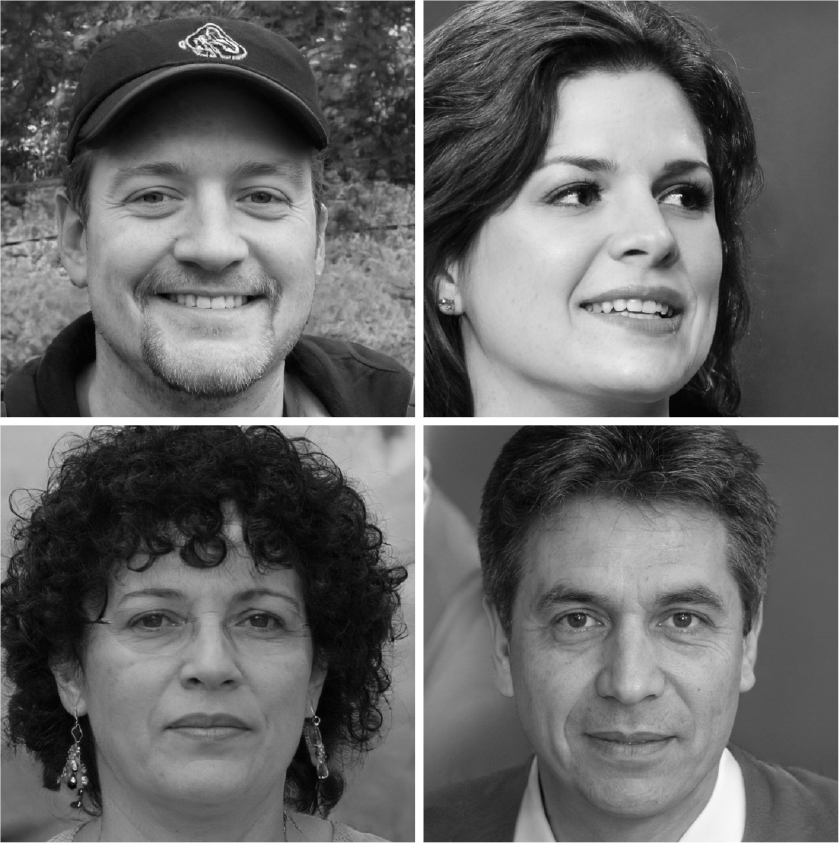

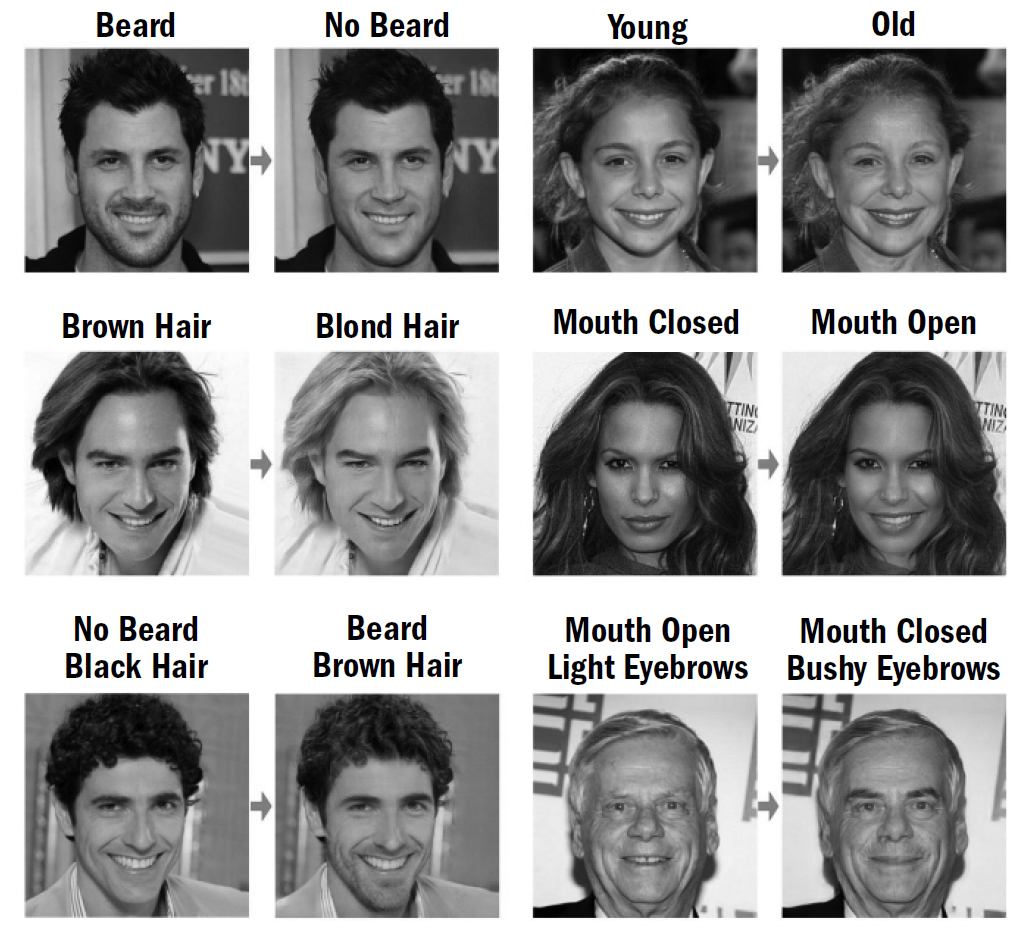

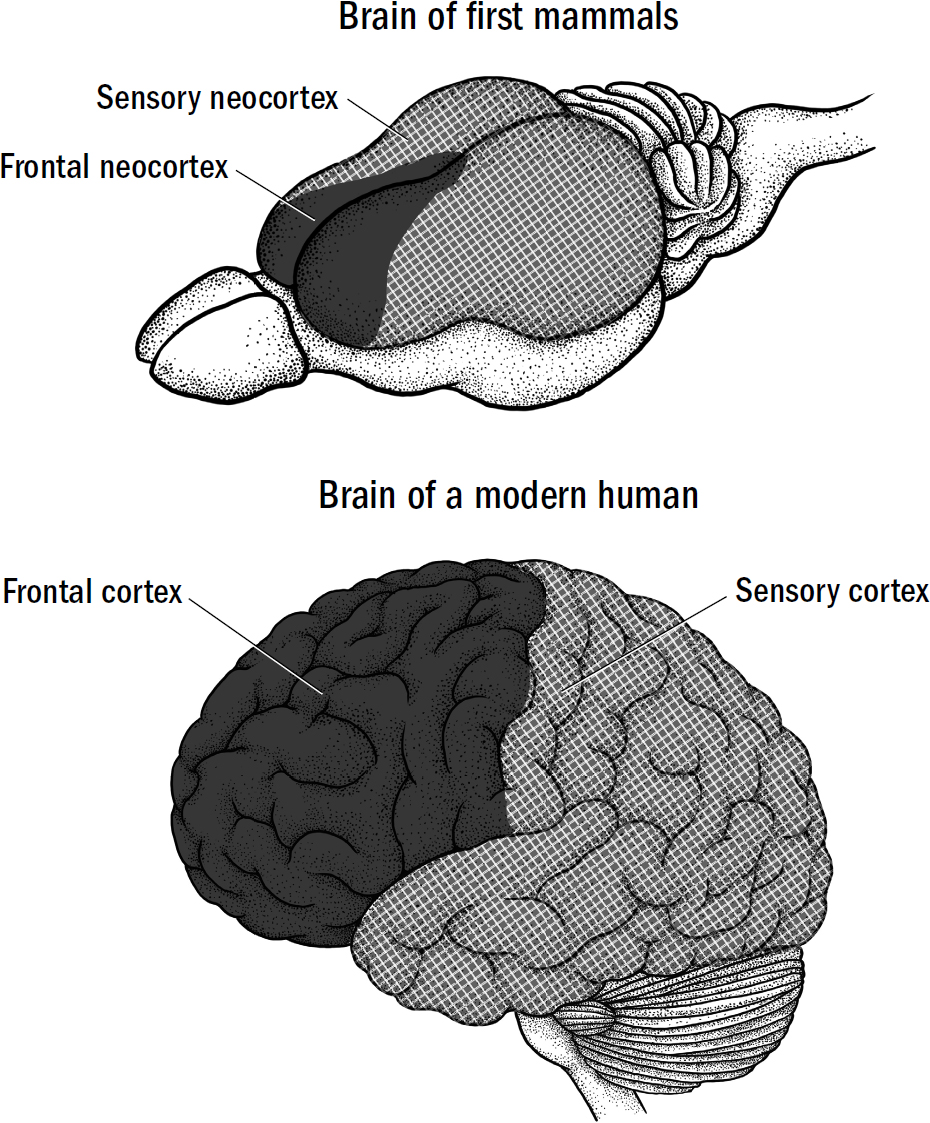

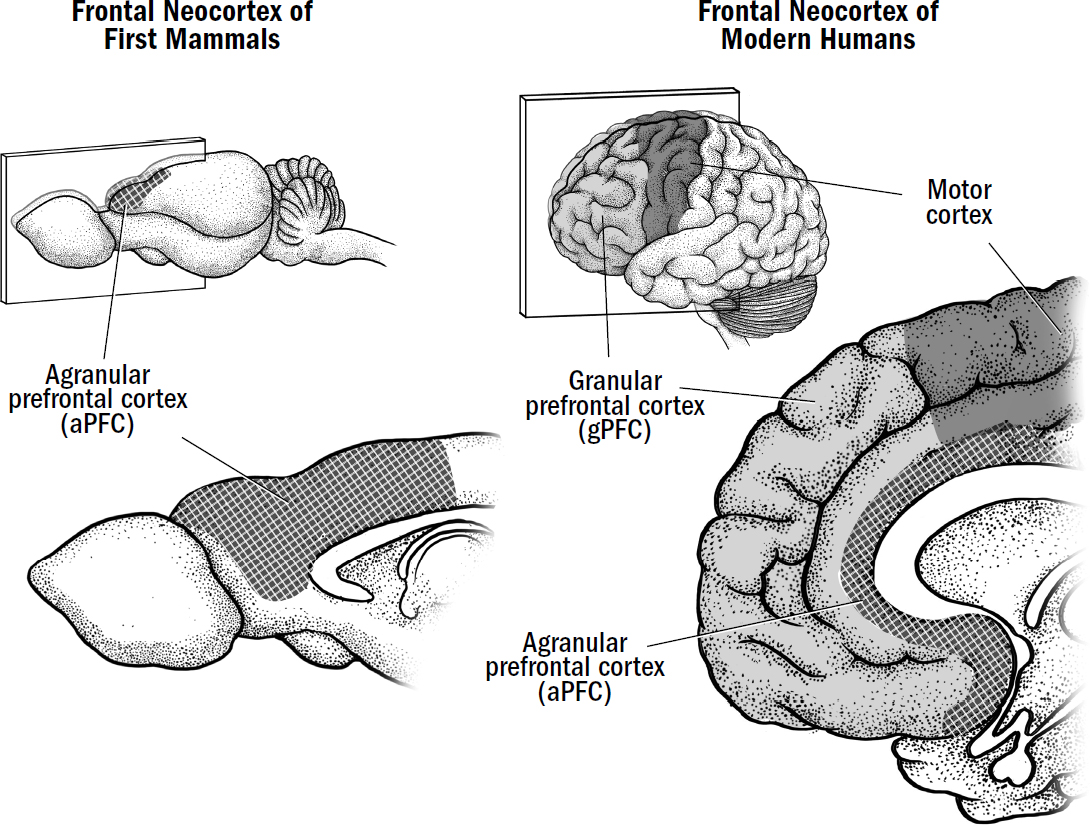

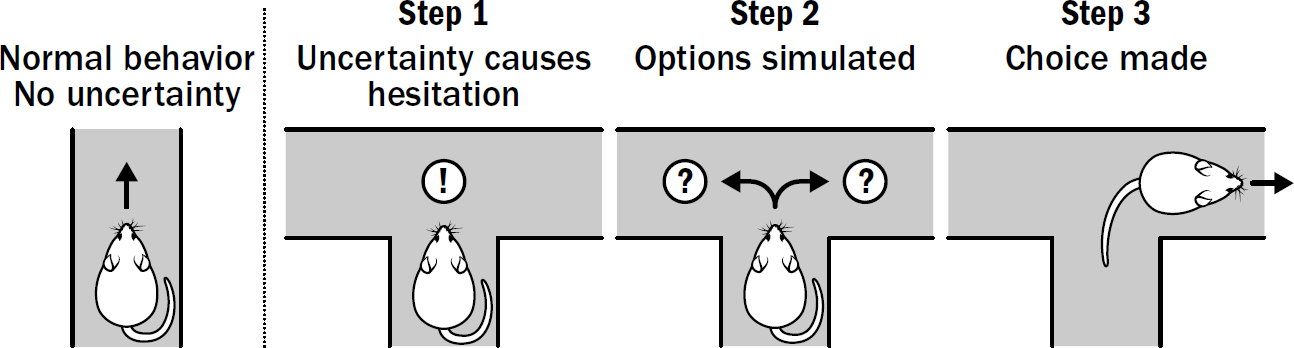

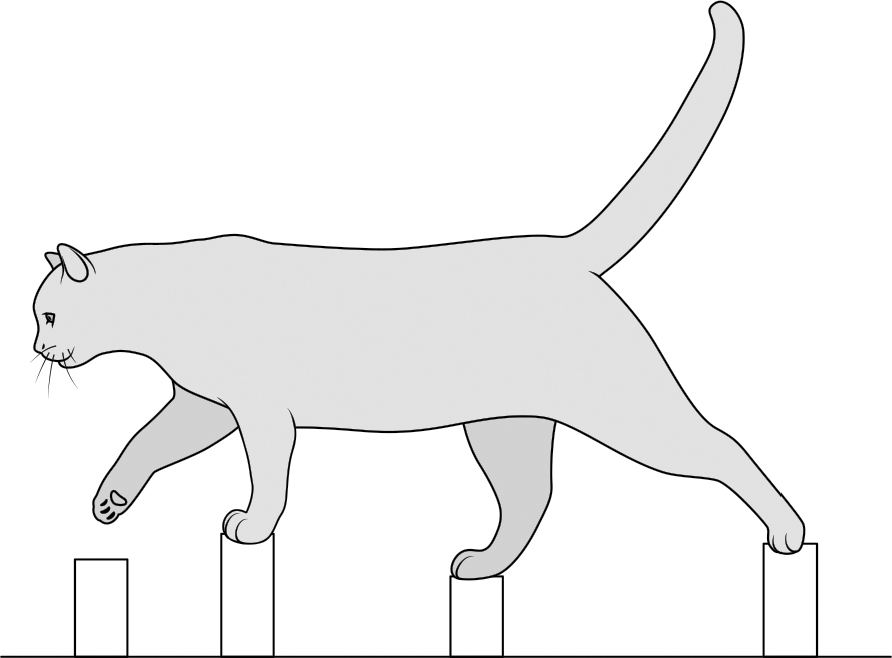

- Breakthrough #3: Simulating and the First Mammals

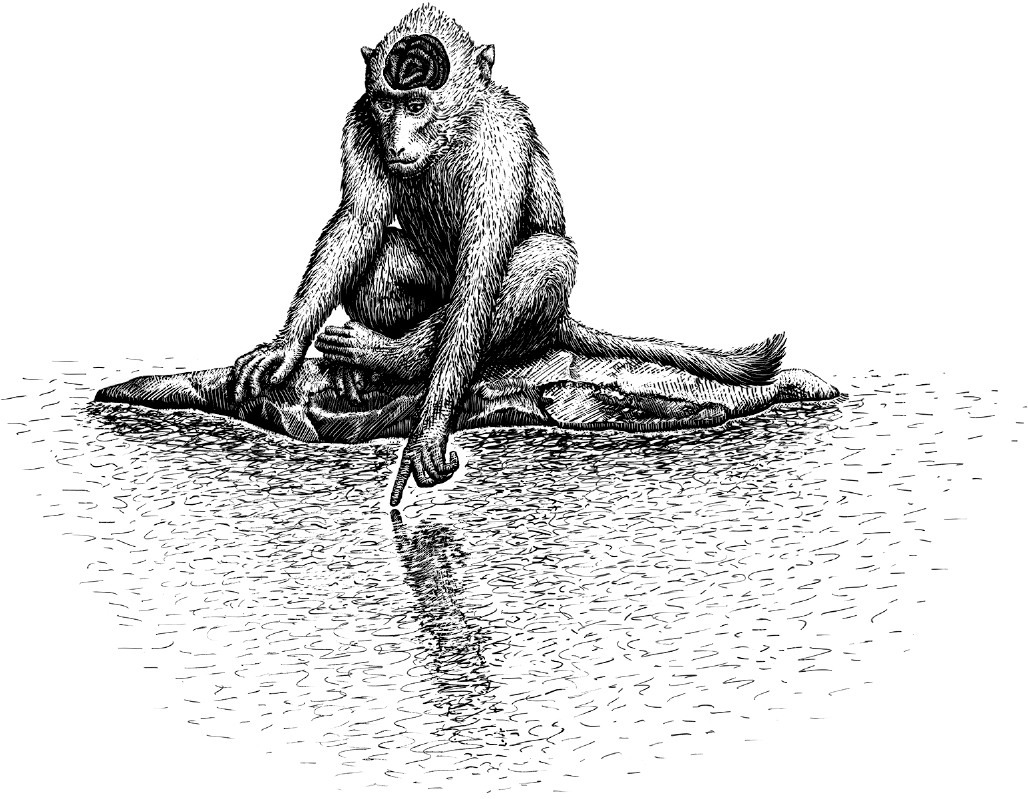

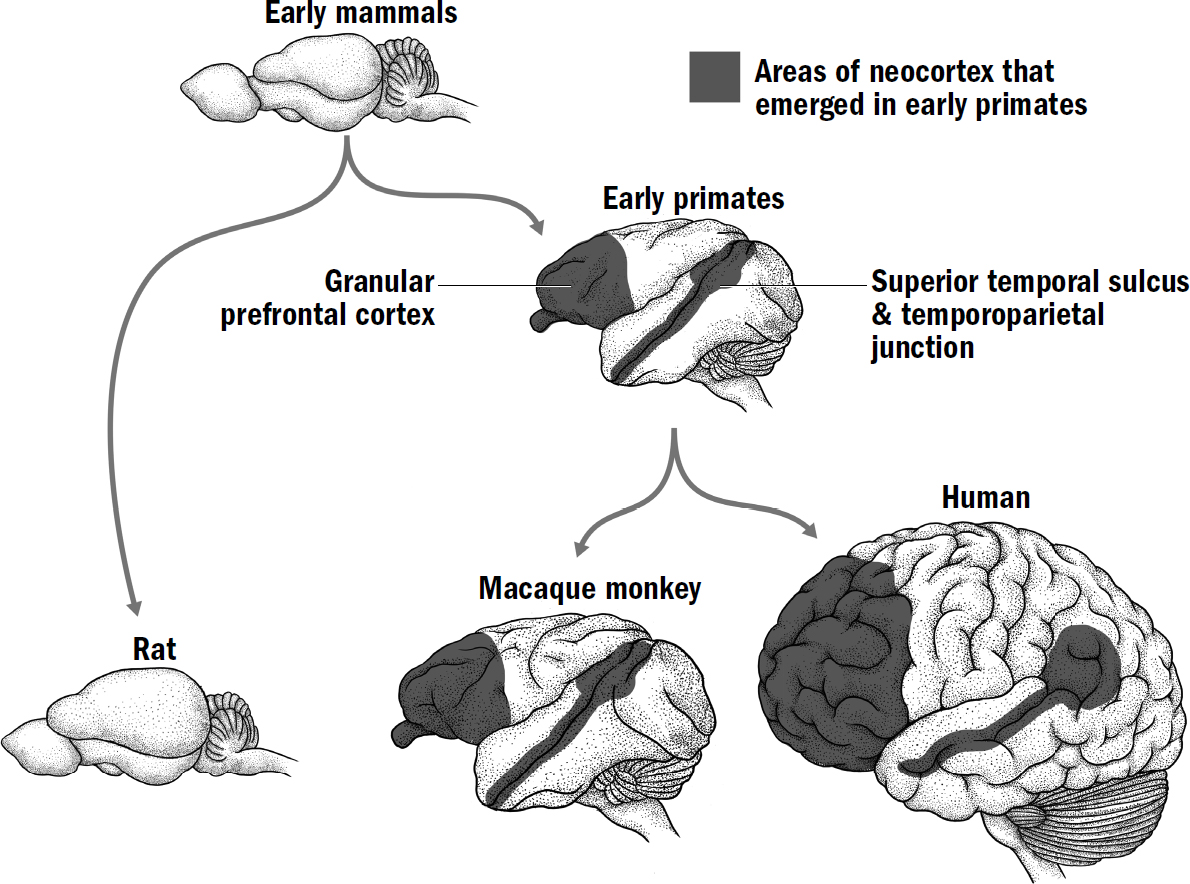

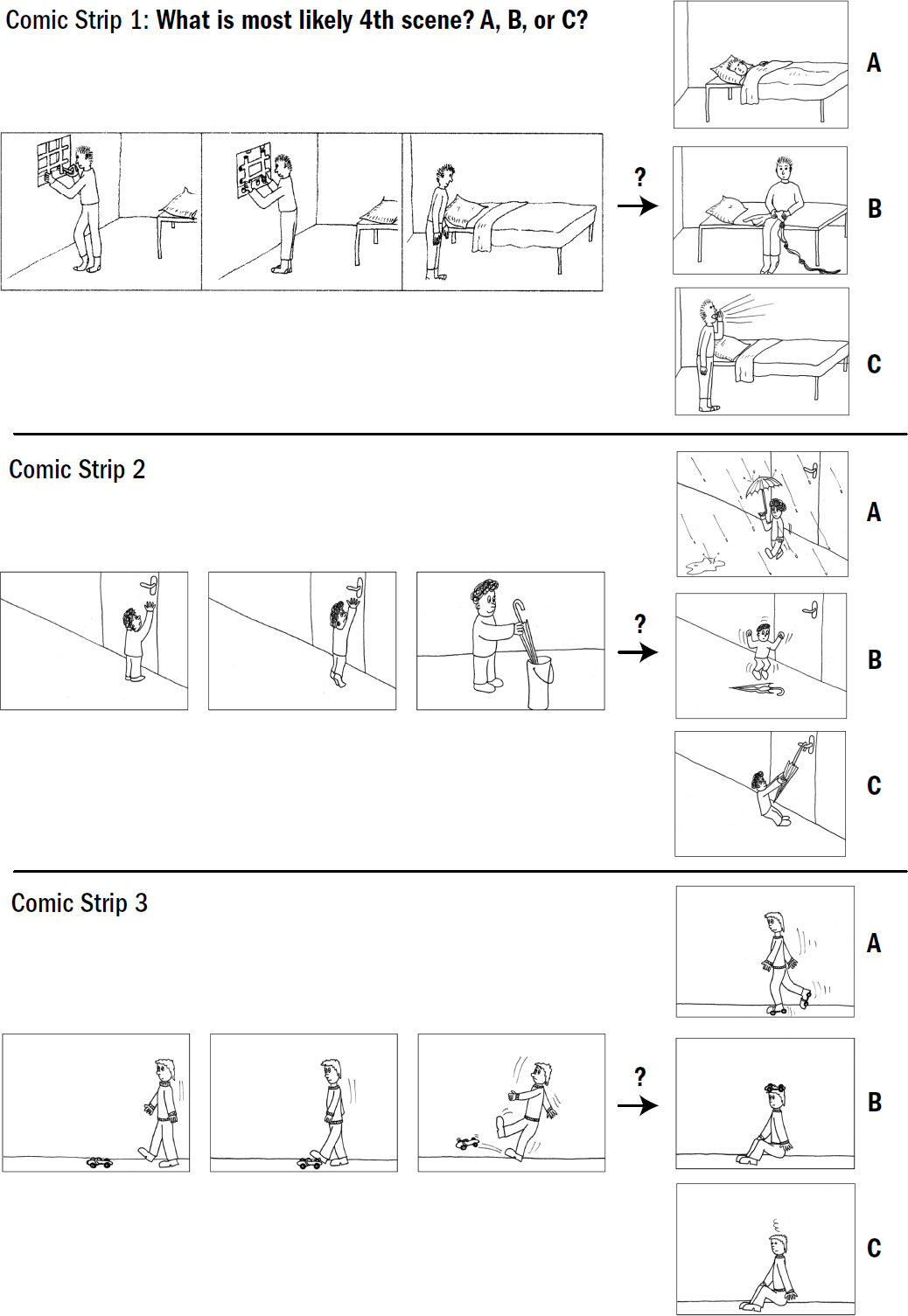

- Breakthrough #4: Mentalizing and the First Primates

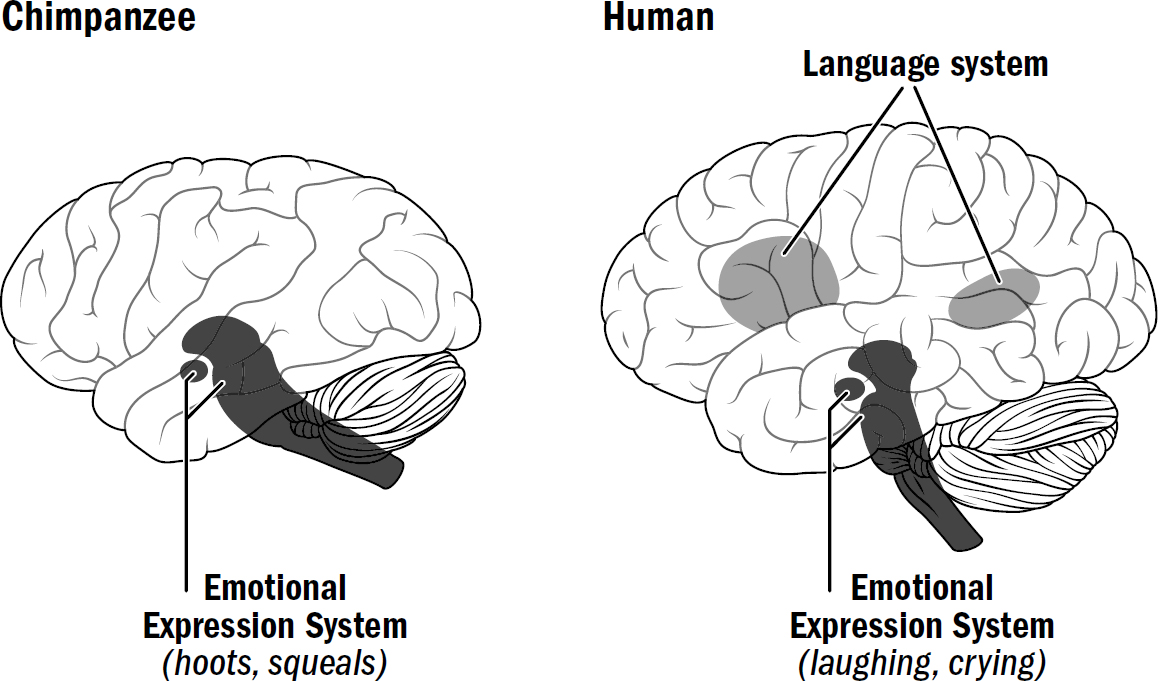

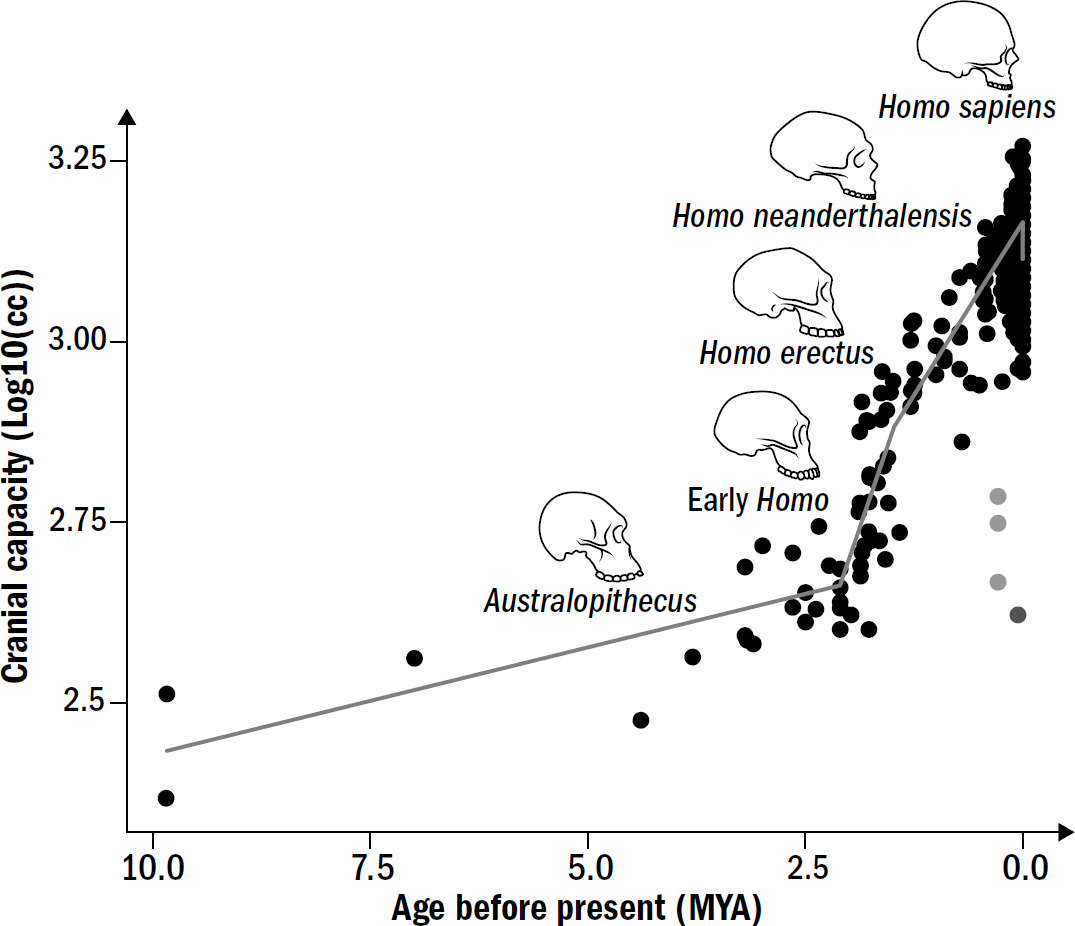

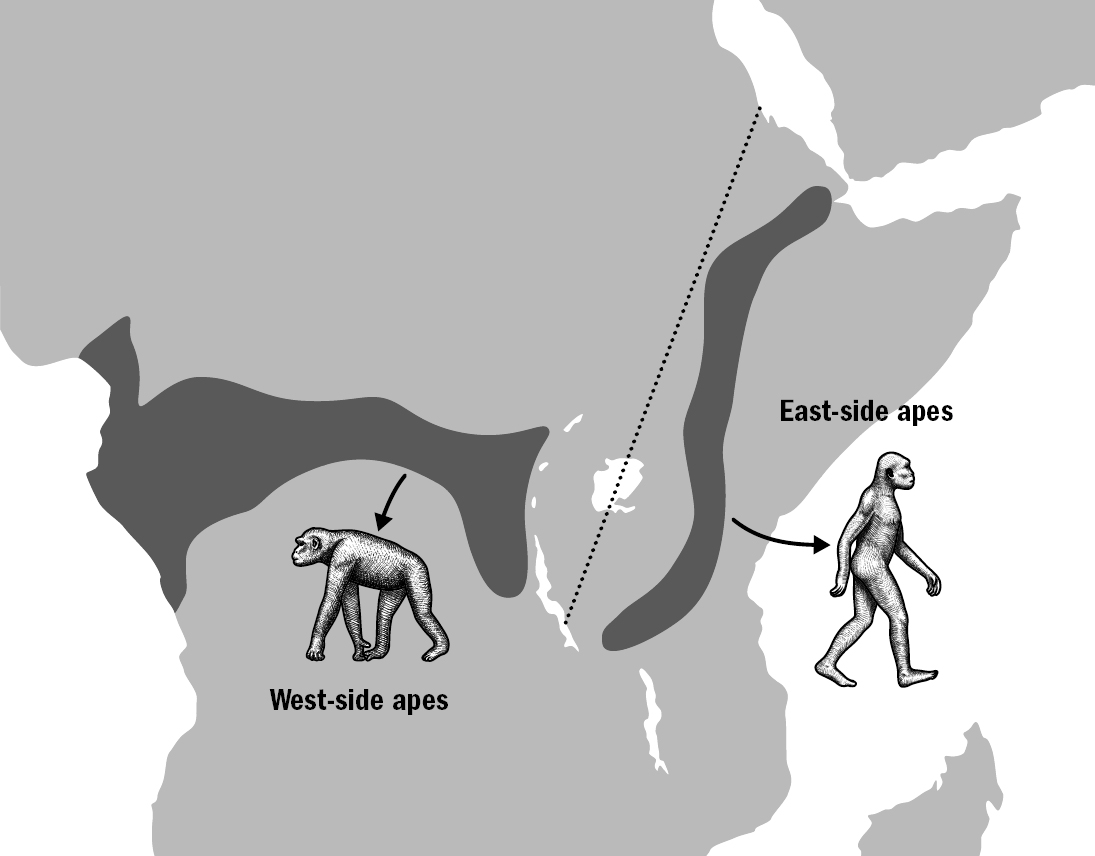

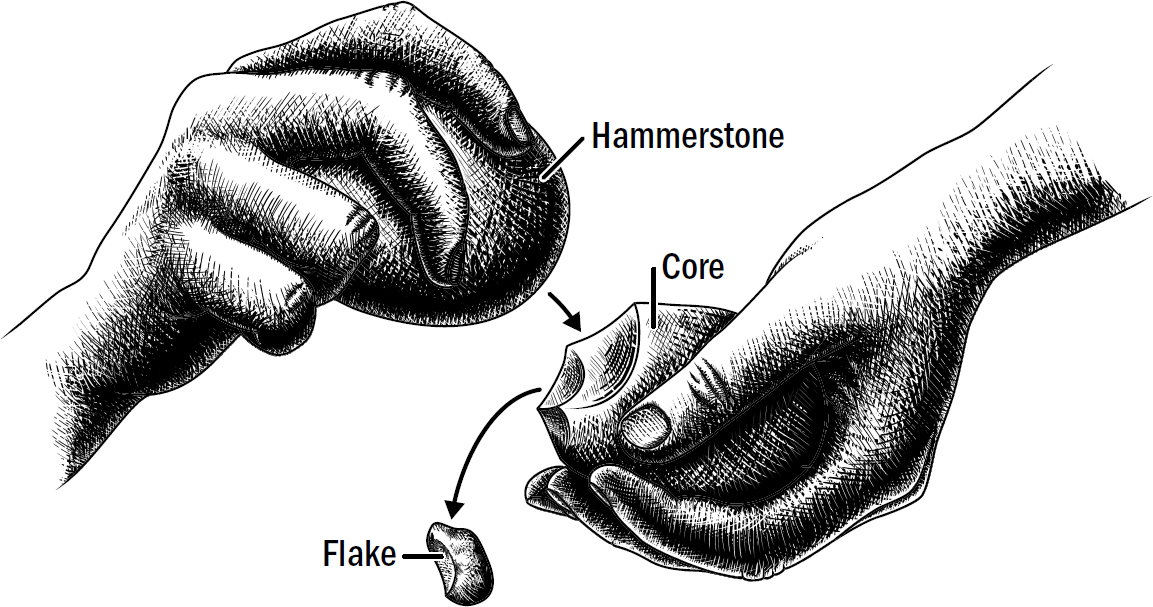

- Breakthrough #5: Speaking and the First Humans

- Conclusion: The Sixth Breakthrough

- Acknowledgments

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Notes

- Index

- About the Author

- Praise for A Brief History of Intelligence

- Copyright

- About the Publisher

Dedication

To my wife, Sydney

Epigraph

In the distant future I see open fields for far more important researches. Psychology will be based on a new foundation, that of the necessary acquirement of each mental power and capacity by gradation. Light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history.

—CHARLES DARWIN IN 1859

Contents

The Basics of Human Brain Anatomy

Breakthrough #1: Steering and the First Bilaterians

4: Associating, Predicting, and the Dawn of Learning

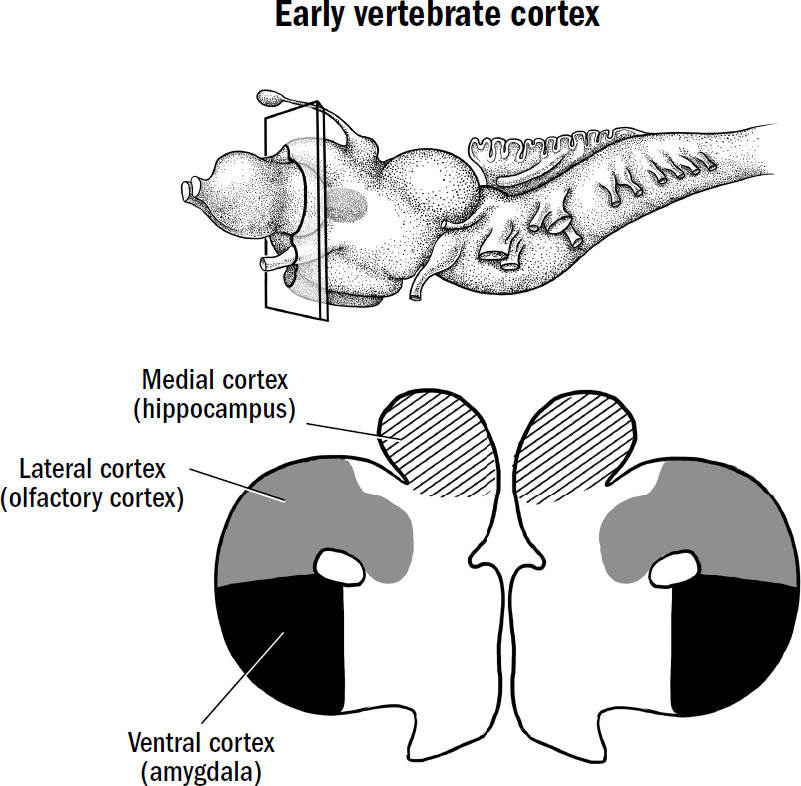

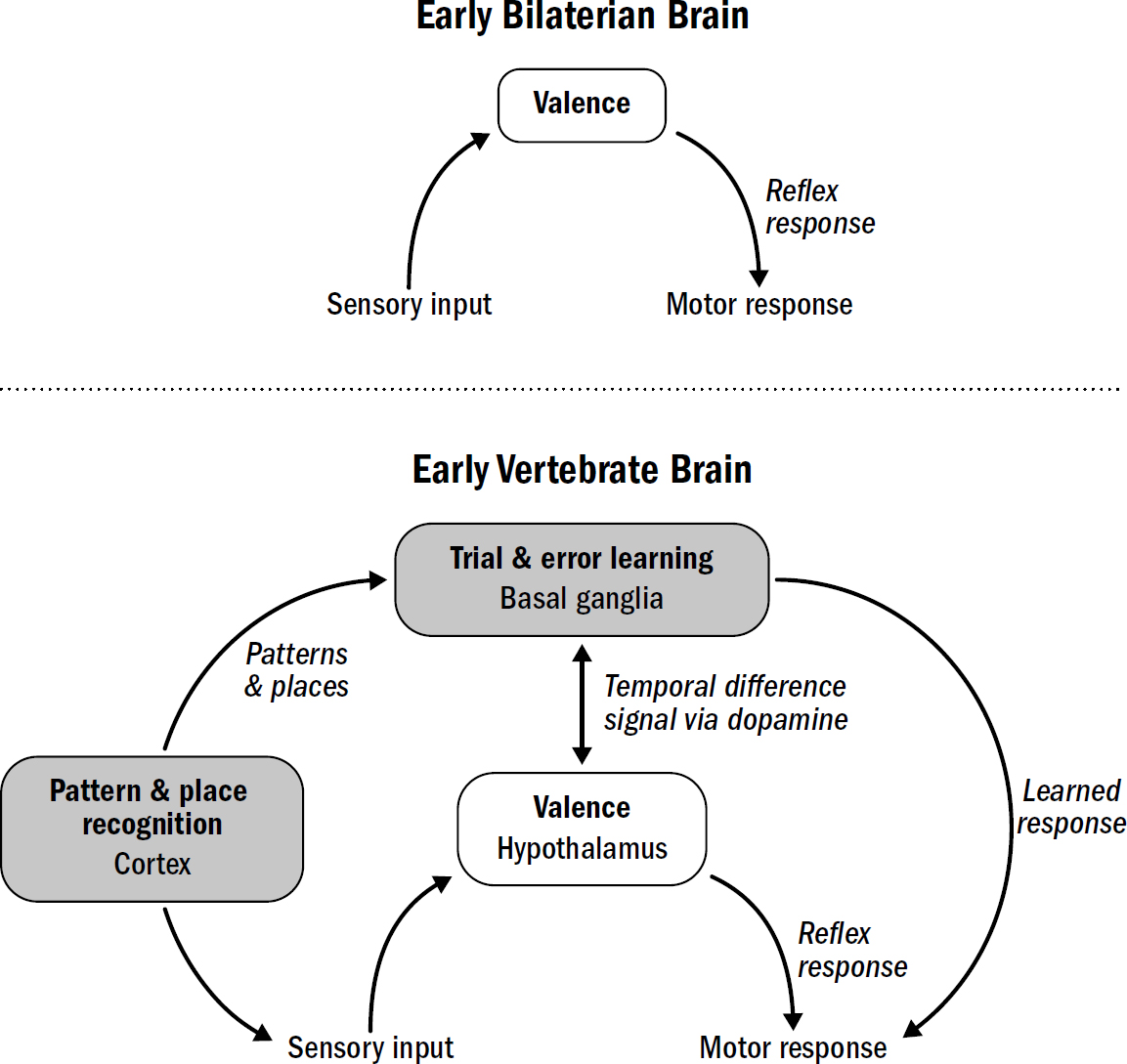

Breakthrough #2: Reinforcing and the First Vertebrates

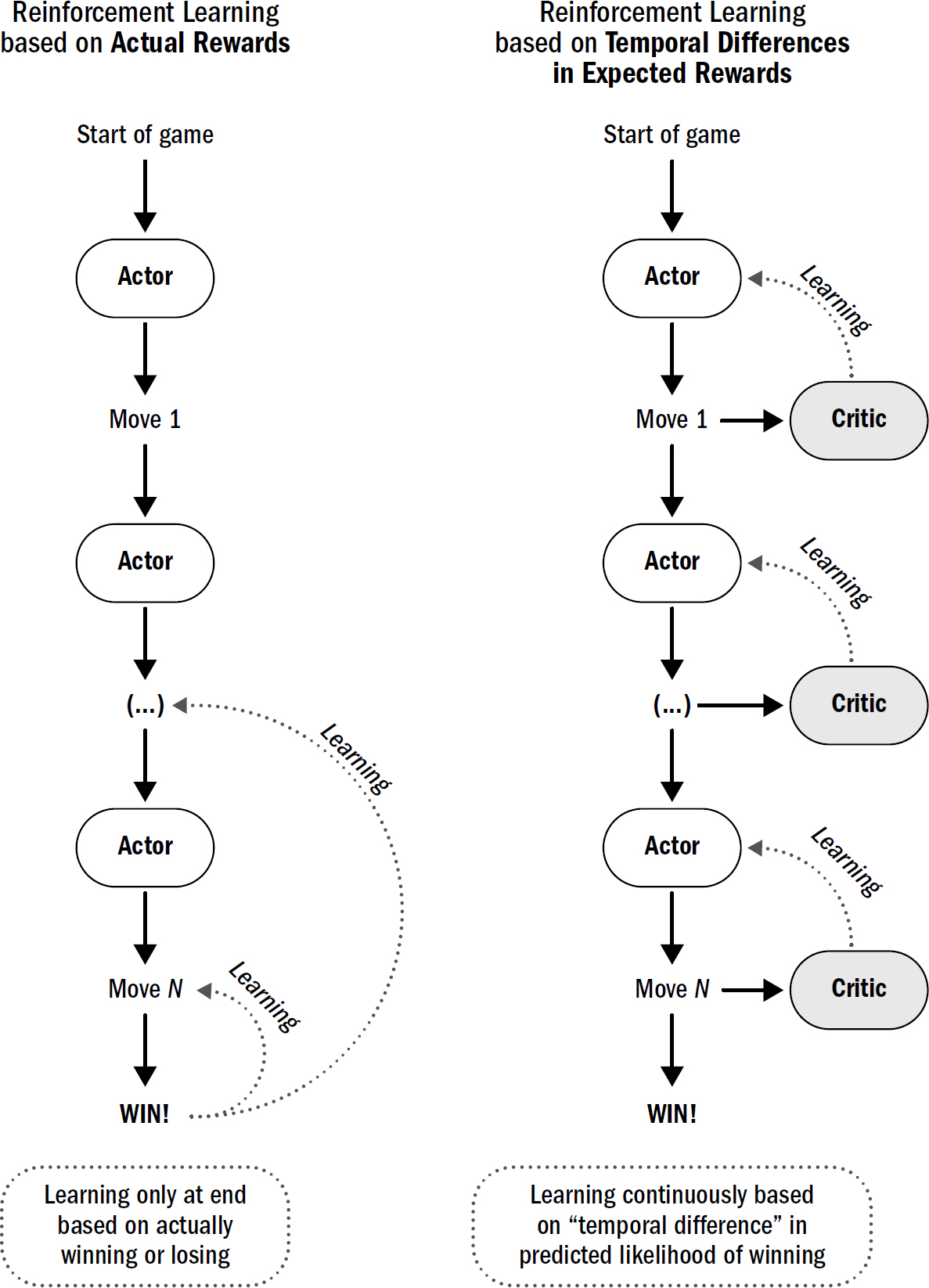

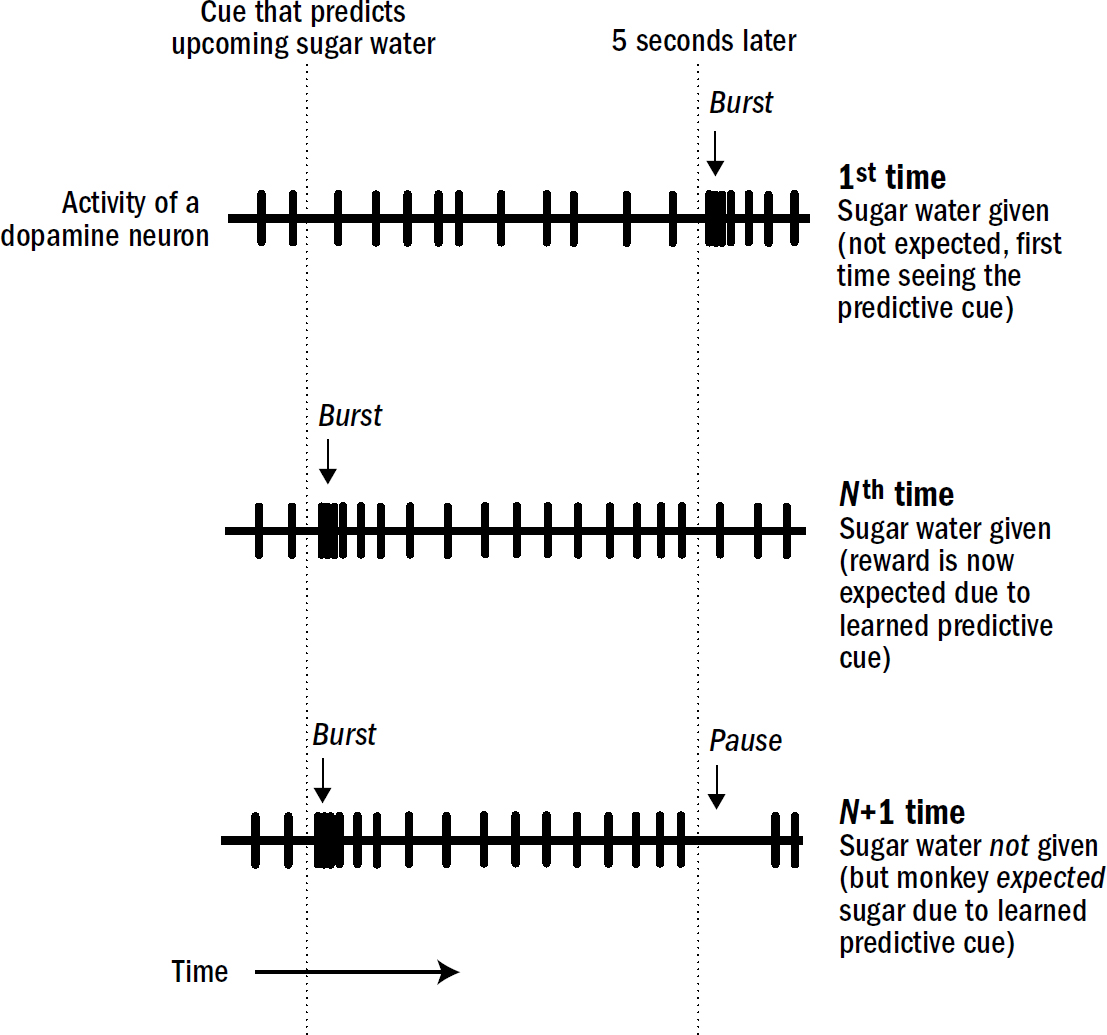

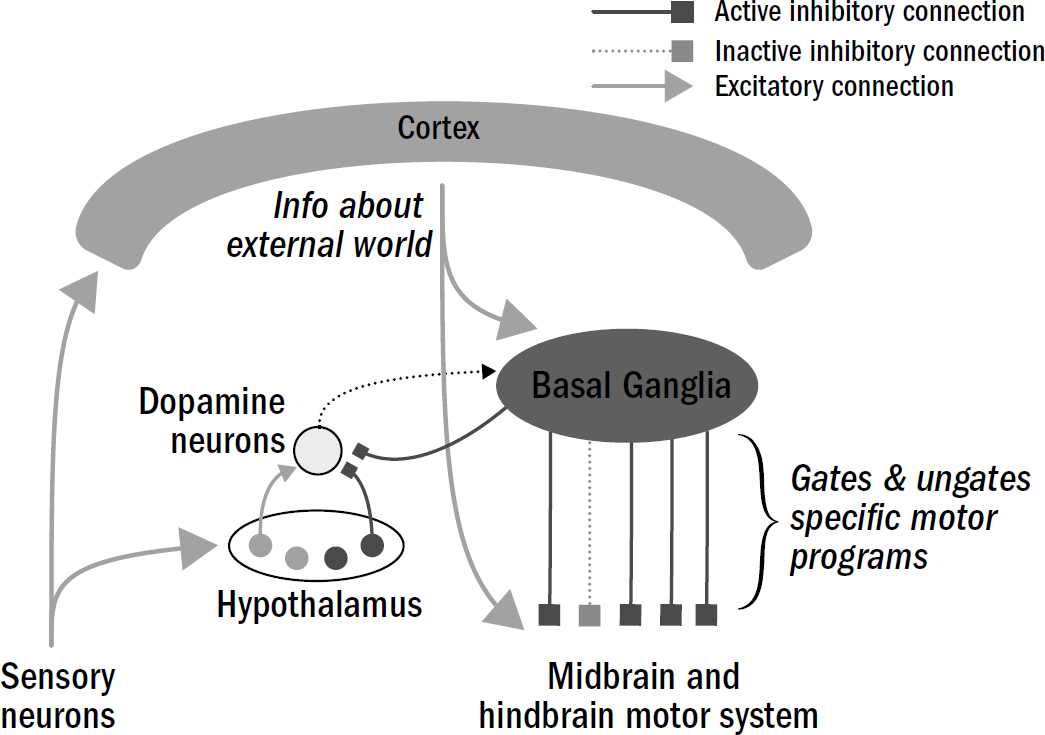

6: The Evolution of Temporal Difference Learning

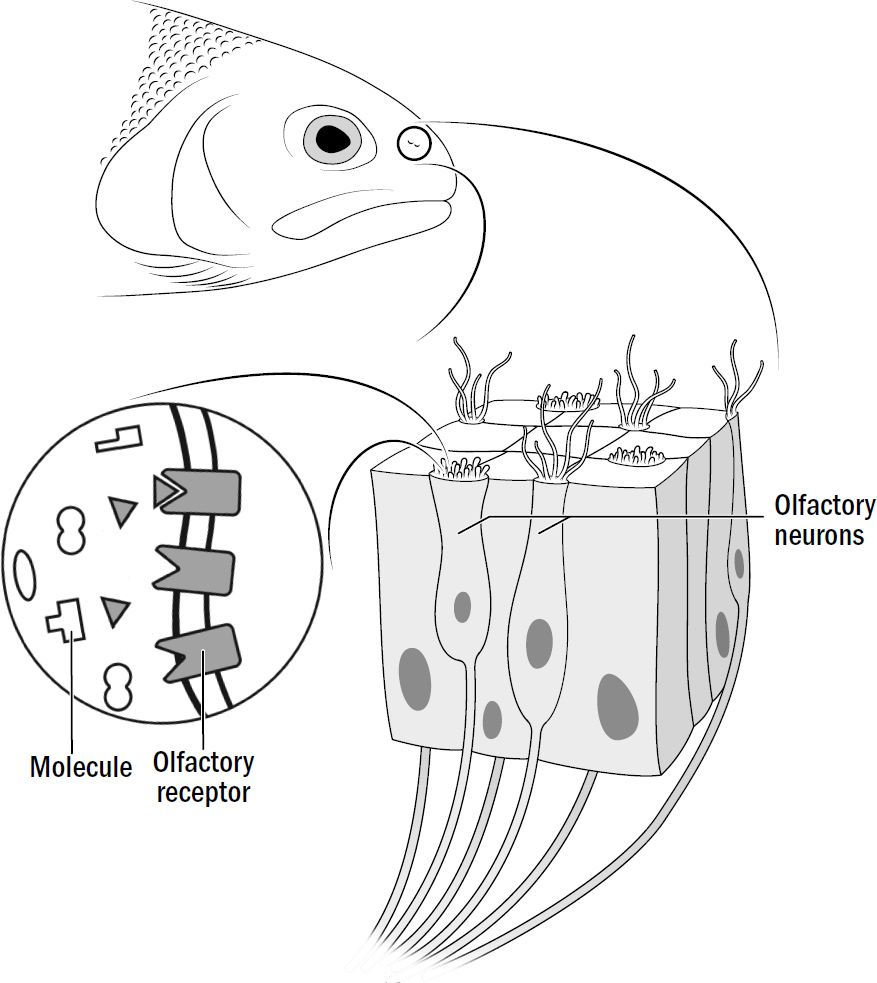

7: The Problems of Pattern Recognition

9: The First Model of the World

Breakthrough #3: Simulating and the First Mammals

11: Generative Models and the Neocortical Mystery

13: Model-Based Reinforcement Learning

14: The Secret to Dishwashing Robots

Breakthrough #4: Mentalizing and the First Primates

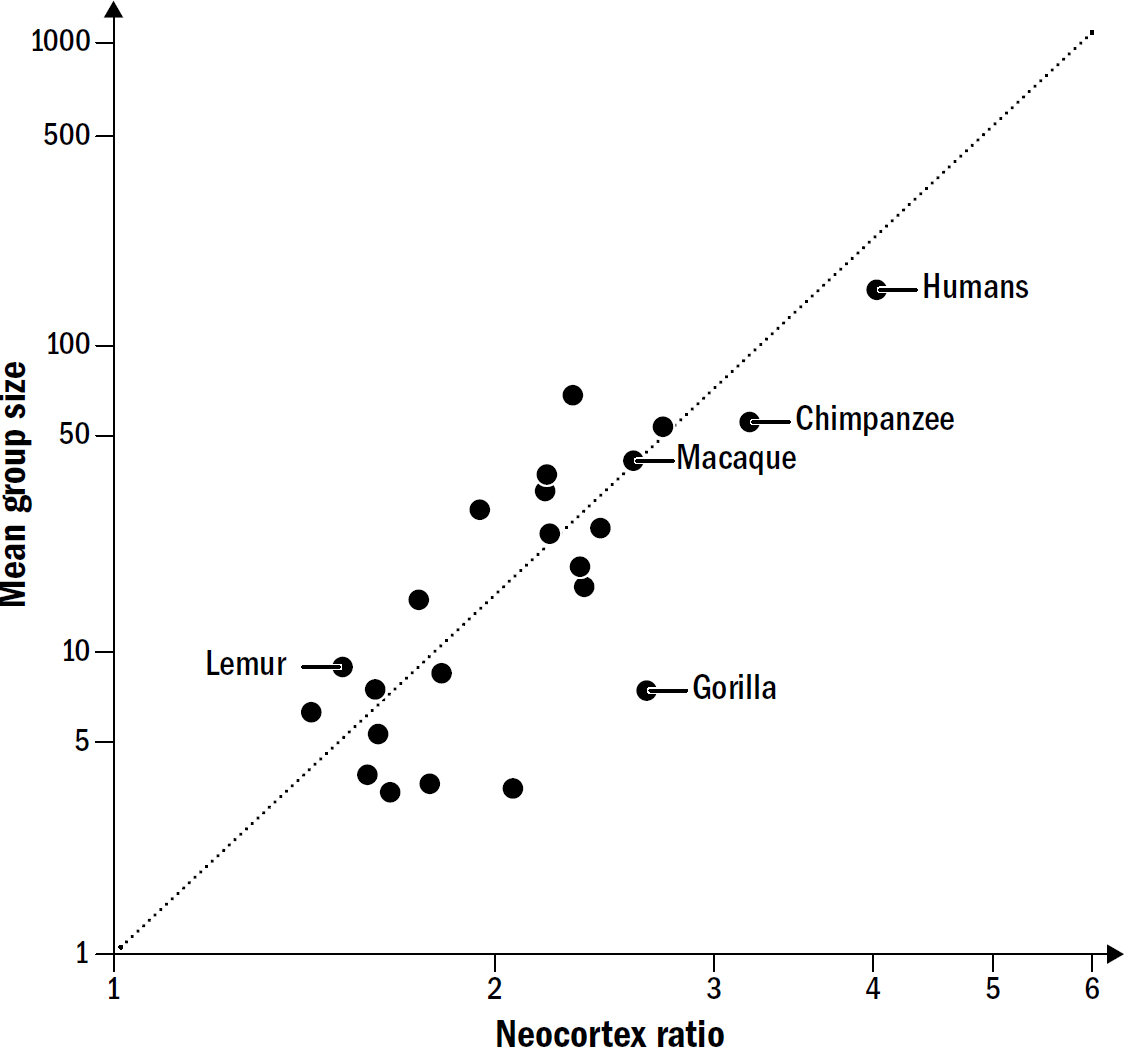

15: The Arms Race for Political Savvy

17: Monkey Hammers and Self-Driving Cars

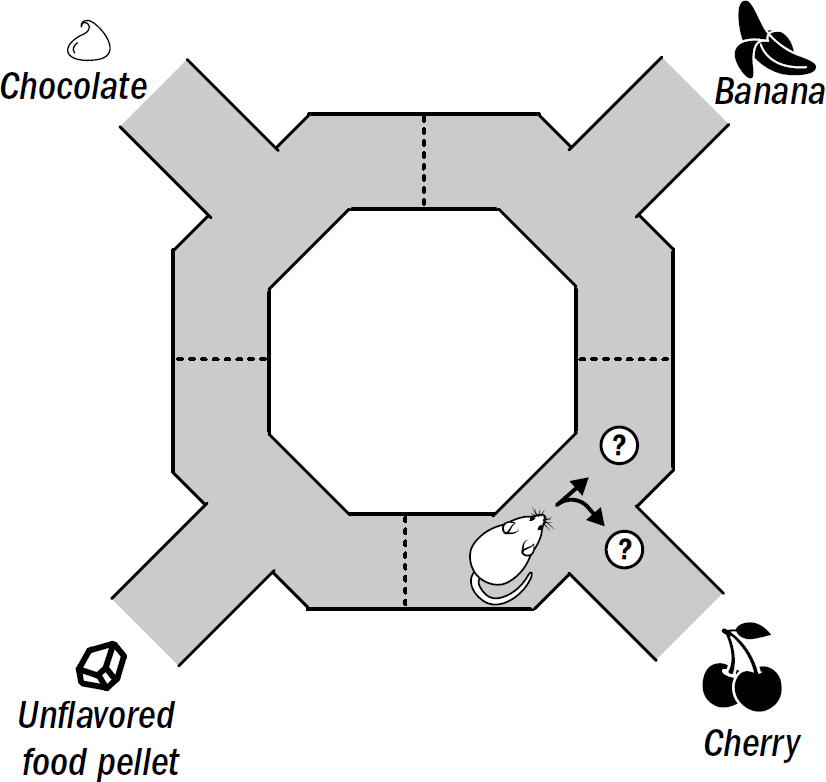

18: Why Rats Can’t Go Grocery Shopping

Breakthrough #5: Speaking and the First Humans

19: The Search for Human Uniqueness

22: ChatGPT and the Window into the Mind

Conclusion: The Sixth Breakthrough

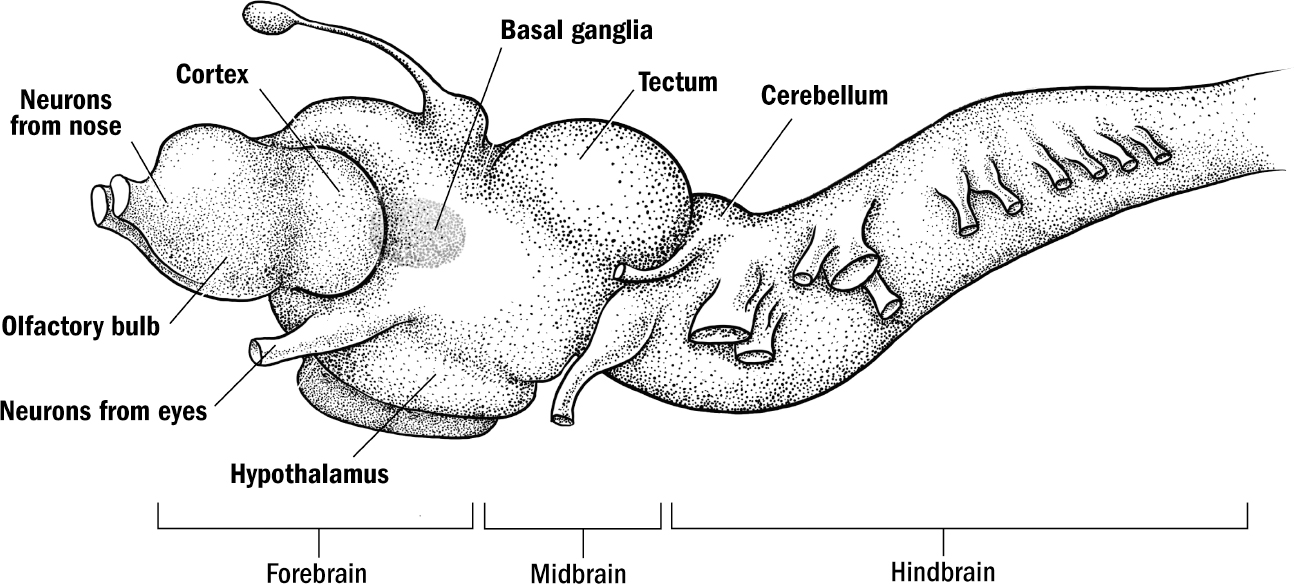

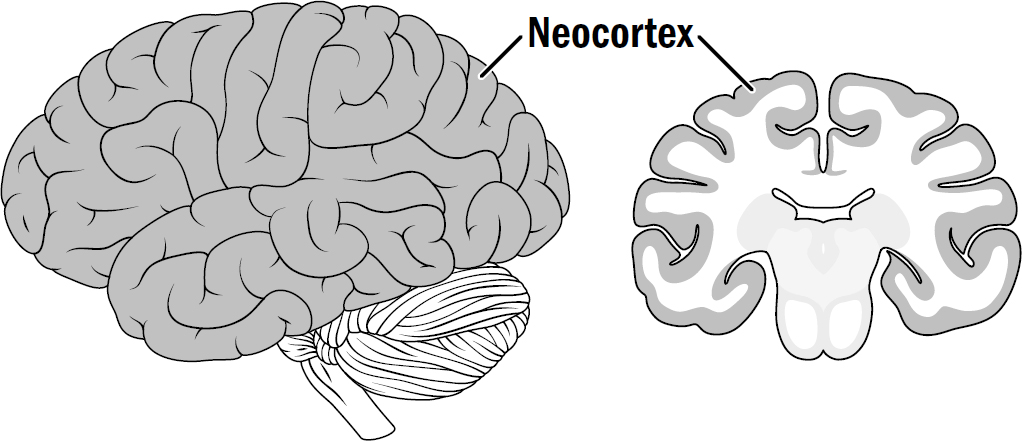

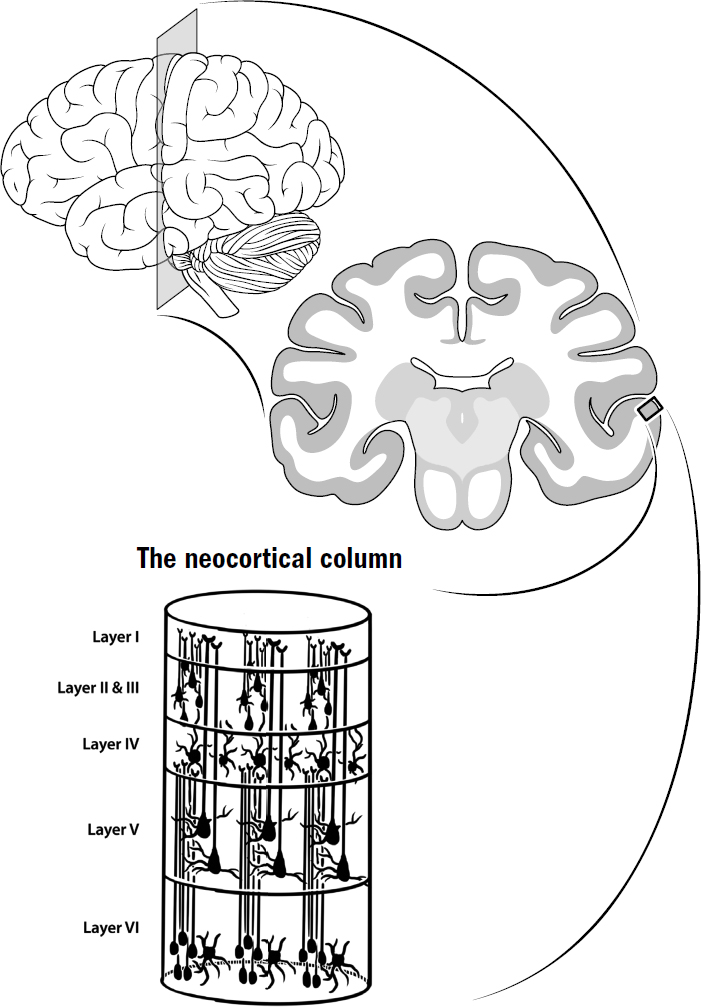

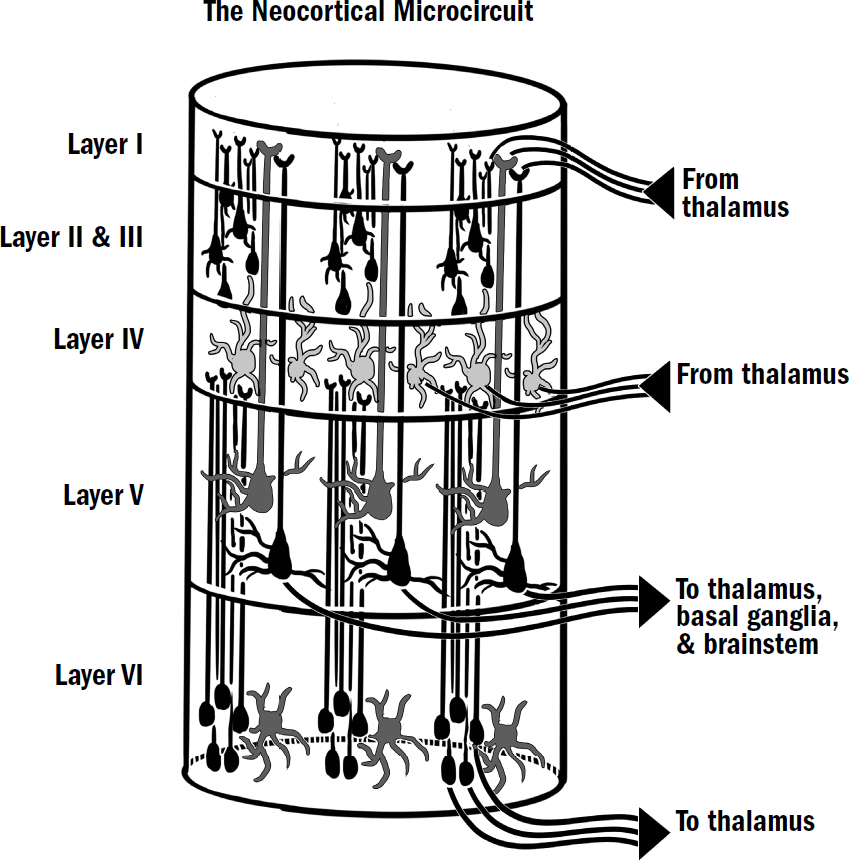

The Basics of Human Brain Anatomy

Original art by Mesa Schumacher

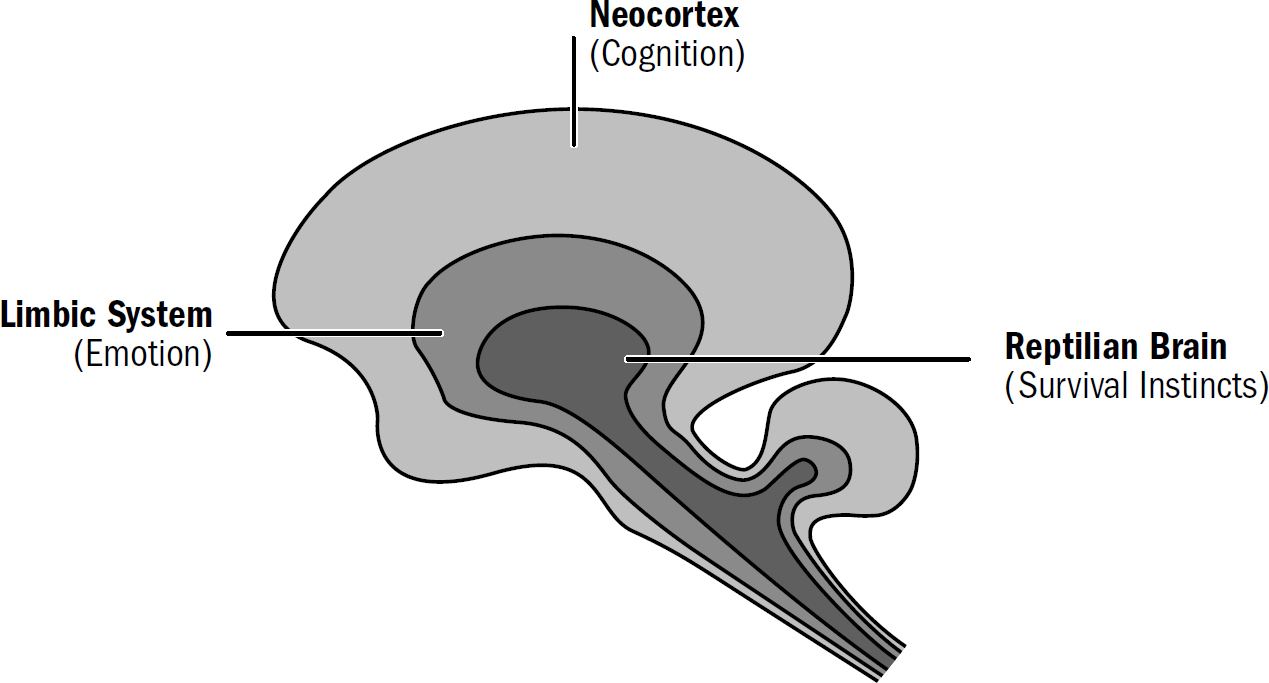

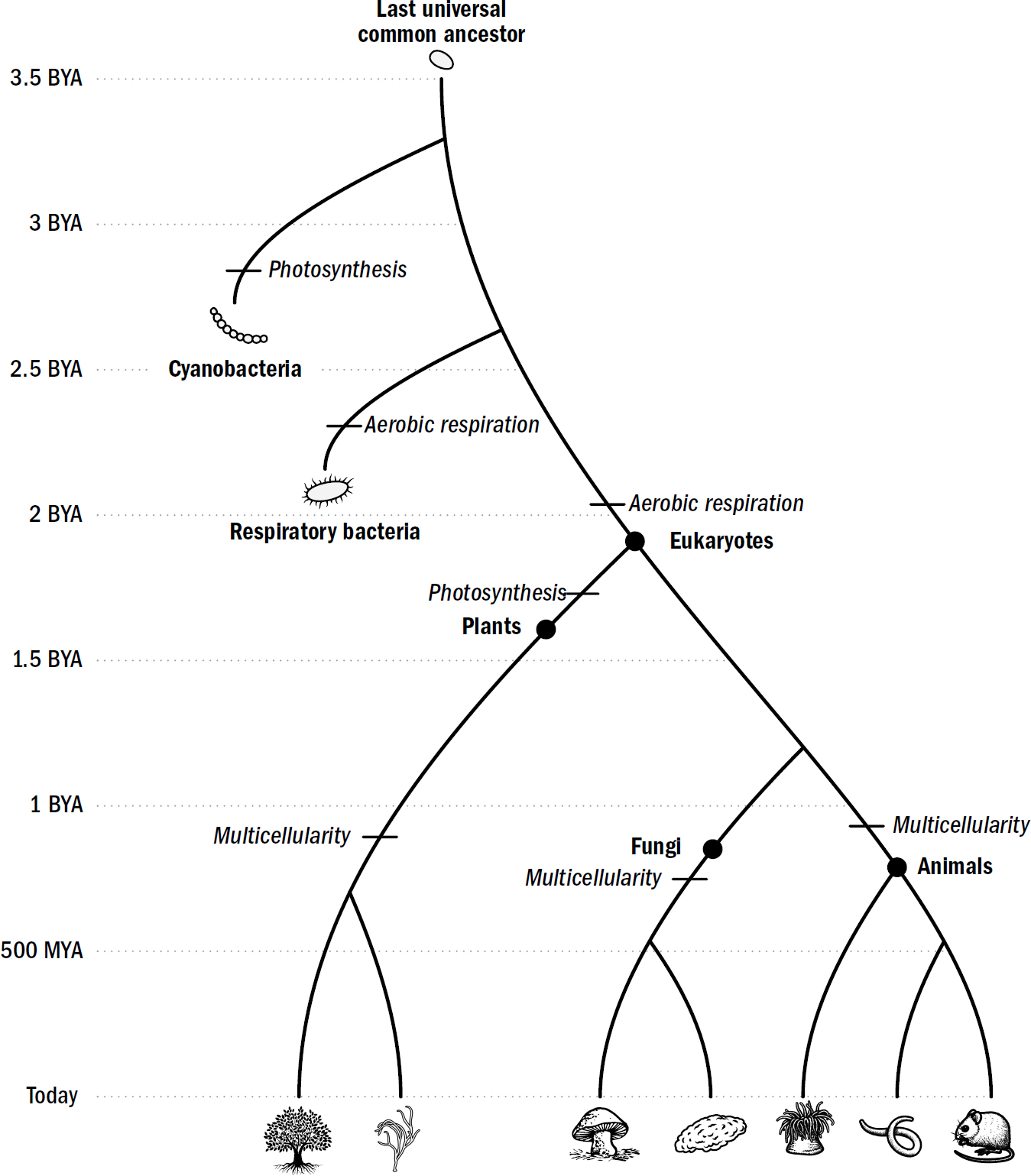

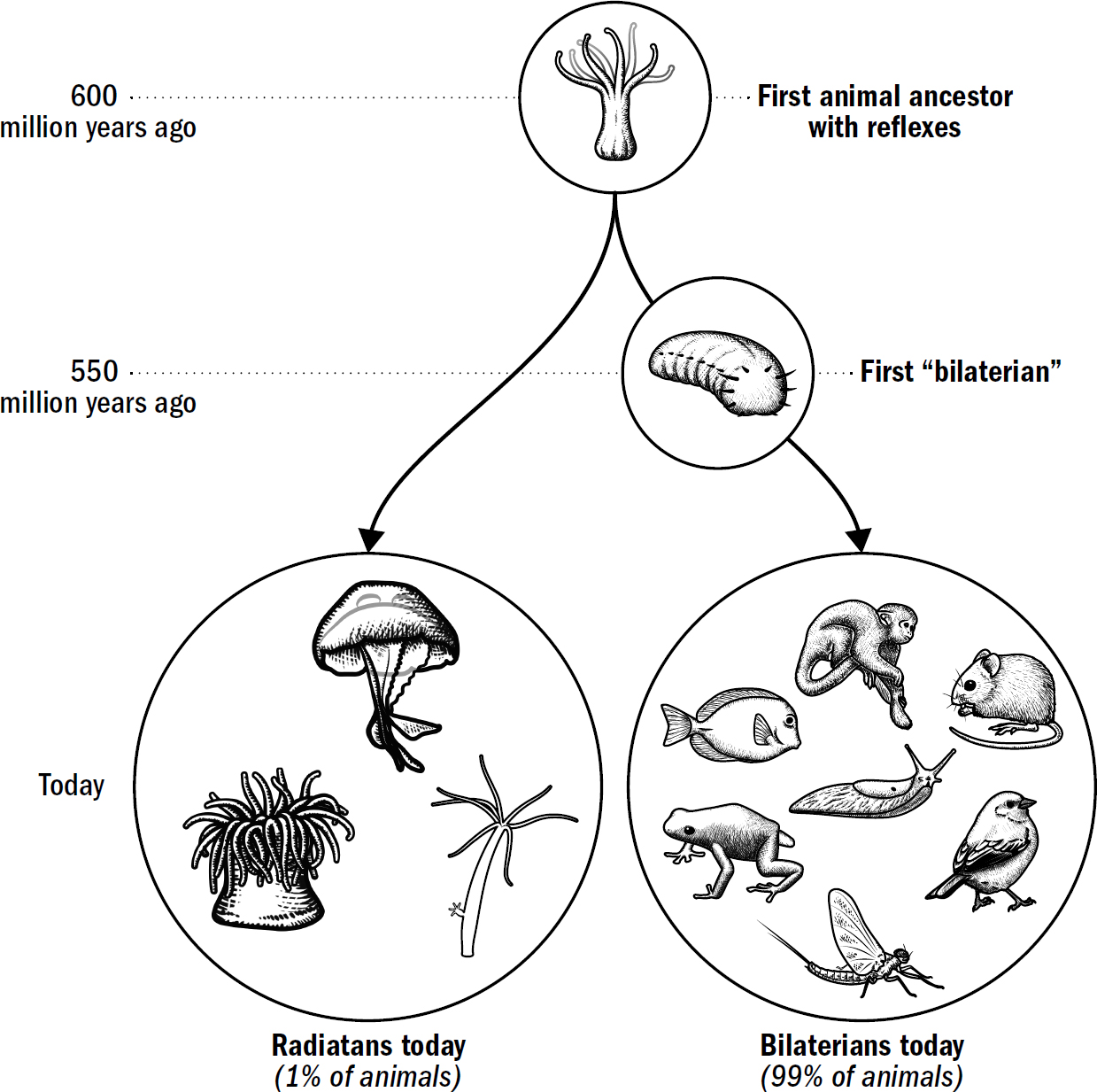

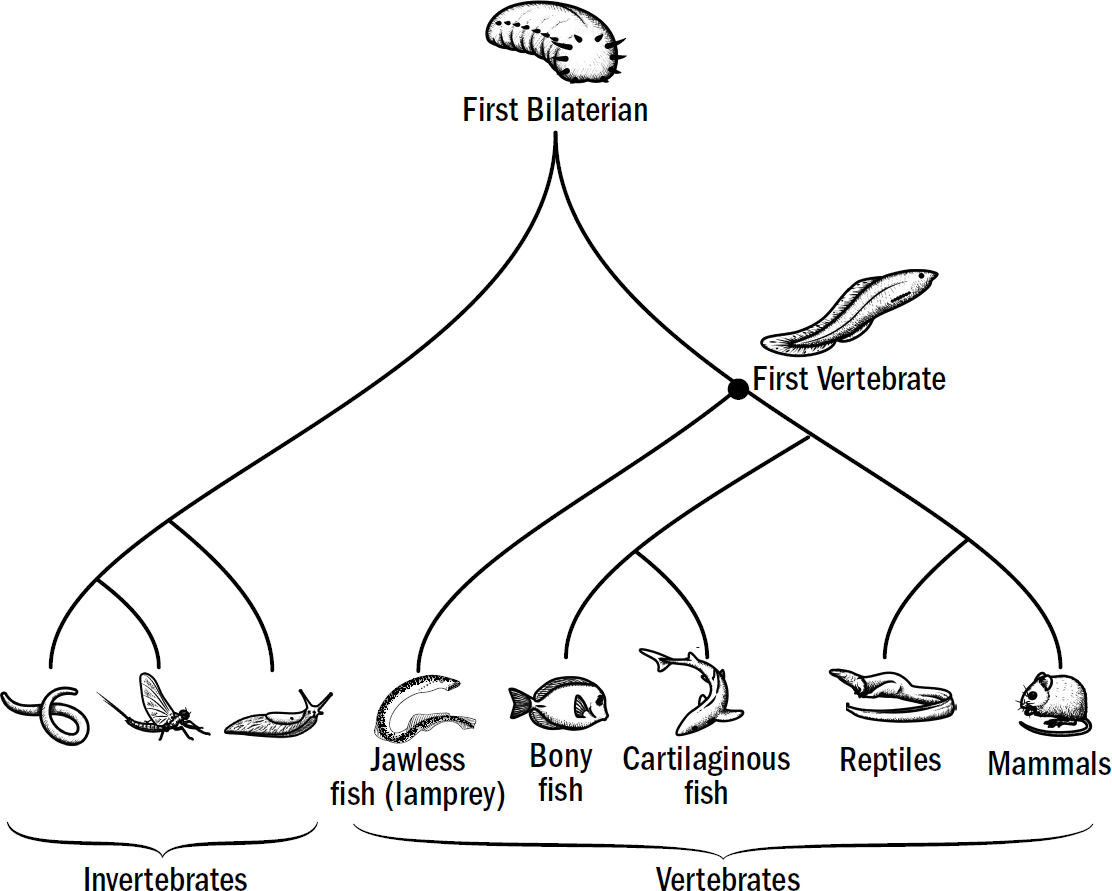

Our Evolutionary Lineage

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

Special thanks to Rebecca Gelernter for creating the incredible original art in this book; Rebecca created the art at the beginning of each Breakthrough section and designed the majority of the figures. Also, a special thanks to Mesa Schumacher for her wonderful original anatomical art of the human, lamprey, monkey, and rat brain that she made specifically for this book.

Introduction

IN SEPTEMBER 1962, during the global tumult of the space race, the Cuban missile crisis, and the recently upgraded polio vaccine, there was a less reported—but perhaps equally critical—milestone in human history: It was in the fall of ’62 that we predicted the future.

Cast onto the newly colorful screens of American televisions was the debut of The Jetsons, a cartoon about a family living one hundred years in the future. In the guise of a sitcom, the show was, in fact, a prediction of how future humans would live, of what technologies would fill their pockets and furnish their homes.

The Jetsons correctly predicted video calls, flat-screen TVs, cell phones, 3D printing, and smartwatches; all technologies that were unbelievable in 1962 and yet were ubiquitous by 2022. However, there is one technology that we have entirely failed to create, one futurist feat that has not yet come to fruition: the autonomous robot named Rosey.

Rosey was a caretaker for the Jetson family, watching after the children and tending to the home. When Elroy—then six years old—was struggling in school, it was Rosey who helped him with his homework. When their fifteen-year-old daughter, Judy, needed help learning how to drive, it was Rosey who gave her lessons. Rosey cooked meals, set the table, and did the dishes. Rosey was loyal, sensitive, and quick with a joke. She identified brewing family tiffs and misunderstandings, intervening to help individuals see one another’s perspective. At one time, she was moved to tears by a poem Elroy wrote for his mother. Rosey herself, in one episode, even fell in love.

In other words, Rosey had the intelligence of a human. Not just the reasoning, common sense, and motor skills needed to perform complex tasks in the physical world, but also the empathizing, perspective taking, and social finesse needed to successfully navigate our social world. In the words of Jane Jetson, Rosey was

Although the The Jetsons correctly predicted cell phones and smartwatches, we still don’t have anything like Rosey. As of this book going to print, even Rosey’s most basic behaviors are still out of reach. It is no secret that the first company to build a robot that can simply load a dishwasher will immediately have a bestselling product. All attempts to do this have failed. It isn’t fundamentally a mechanical problem; it’s an intellectual one—the ability to identify objects in a sink, pick them up appropriately, and load them without breaking anything has proven far more difficult than previously thought.

Of course, even though we do not yet have Rosey, the progress in the field of artificial intelligence (AI) since 1962 has been remarkable. AI can now beat the best humans in the world at numerous games of skill, including chess and Go. AI can recognize tumors in radiology images as well as human radiologists. AI is on the cusp of autonomously driving cars. And as of the last few years, new advancements in large language models are enabling products like ChatGPT, which launched in fall 2022, to compose poetry, translate between languages at will, and even write code. To the chagrin of every high school teacher on planet Earth, ChatGPT can instantly compose a remarkably well written and original essay on almost any topic that an intrepid student might ask of it. ChatGPT can even pass the bar exam, scoring better than 90 percent of lawyers.

Along this journey, as AI keeps getting smarter, it is becoming harder to measure our progress toward this goal. If an AI system outperforms humans on a task, does it mean that the AI system has captured how humans solve the task? Does a calculator—capable of crunching numbers faster than a human—actually understand math? Does ChatGPT—scoring better on the bar exam than most lawyers—actually understand the law? How can we tell the difference, and in what circumstances, if any, does the difference even matter?

In 2021, over a year before the release of ChatGPT—the chatbot that is now rapidly proliferating throughout every nook and cranny of society—I was using its precursor, a large language model called GPT-3. GPT-3 was trained on large quantities of text (large as in the entire internet), and then used this corpus to try to pattern match the most likely response to a prompt. When asked, “What are two reasons that a dog might be in a bad mood?” it responded, “Two reasons a dog might be in a bad mood are if it is hungry or if it is hot.” Something about the new architecture of these systems enabled them to answer questions with what at least seemed like a remarkable degree of intelligence. These models were able to generalize facts they had read about (like the Wikipedia pages about dogs and other pages about causes of bad moods) to new questions they had never seen. In 2021, I was exploring possible applications of these new language models—could they be used to provide new support systems for mental health, or more seamless customer service, or more democratized access to medical information?

Indeed, the discrepancies between artificial intelligence and human intelligence are nothing short of perplexing. Why is it that AI can crush any human on earth in a game of chess but can’t load a dishwasher better than a six-year-old?

We struggle to answer these questions because we don’t yet understand the thing we are trying to re-create. All of these questions are, in essence, not questions about AI, but about the nature of human intelligence itself—how it works, why it works the way it does, and as we will soon see, most importantly, how it came to be.

Nature’s Hint

When humanity wanted to understand flight, we garnered our first inspiration from birds; when George de Mestral invented Velcro, he got the idea from burdock fruits; when Benjamin Franklin sought to explore electricity, his first sparks of understanding came from lightning. Nature has, throughout the history of human innovation, long been a wondrous guide.

Nature also offers us clues as to how intelligence works—the clearest locus of which is, of course, the human brain. But in this way, AI is unlike these other technological innovations; the brain has proven to be more unwieldy and harder to decipher than either wings or lightning. Scientists have been investigating how the brain works for millennia, and while we have made progress, we do not yet have satisfying answers.

The problem is complexity.

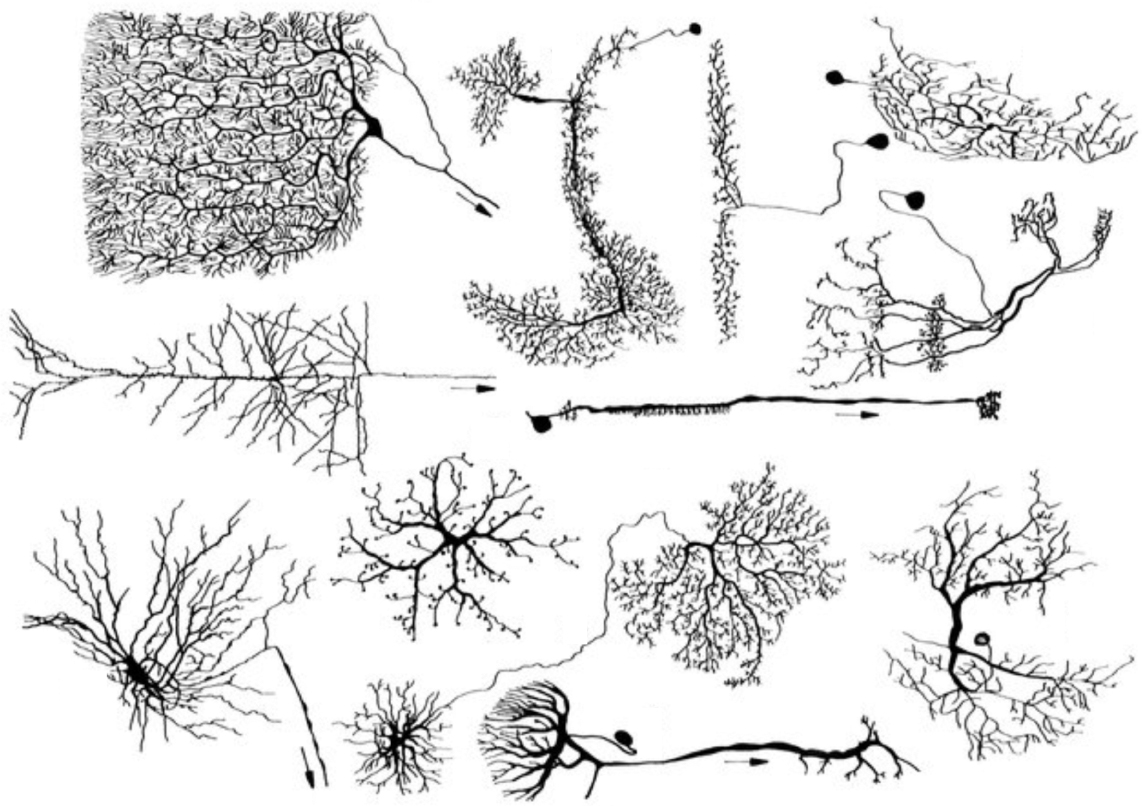

The human brain contains eighty-six billion neurons and over a hundred trillion connections. Each of those connections is so minuscule—less than thirty nanometers wide—that they can barely be seen under even the most powerful microscopes. These connections are bunched together in a tangled mess—within a single cubic millimeter (the width of a single letter on a penny), there are

But the sheer number of connections is only one aspect of what makes the brain complex; even if we mapped the wiring of each neuron we would still be far from understanding how the brain works. Unlike the electrical connections in your computer, where wires all communicate using the same signal—electrons—across each of these neural connections, hundreds of different chemicals are passed, each with completely different effects. The simple fact that two neurons connect to each other tells us little about what they are communicating. And worst of all, these connections themselves are in a constant state of change, with some neurons branching out and forming new connections, while others are retracting and removing old ones. Altogether, this makes reverse engineering how the brain works an ungodly task.

Studying the brain is both tantalizing and infuriating. One inch behind your eyes is the most awe-inspiring marvel of the universe. It houses the secrets to the nature of intelligence, to building humanlike artificial intelligence, to why we humans think and behave the way we do. It is right there, reconstructed millions of times per year with every newly born human. We can touch it, hold it, dissect it, we are literally made of it, and yet its secrets remain out of reach, hidden in plain sight.

If we want to reverse-engineer how the brain works, if we want to build Rosey, if we want to uncover the hidden nature of human intelligence, perhaps the human brain is not nature’s best clue. While the most intuitive place to look to understand the human brain is, naturally, inside the human brain itself, counterintuitively, this may be the last place to look. The best place to start may be in dusty fossils deep in the Earth’s crust, in microscopic genes tucked away inside cells throughout the animal kingdom, and in the brains of the many other animals that populate our planet.

In other words, the answer might not be in the present, but in the hidden remnants of a long time past.

The Missing Museum of Brains

—GEOFFREY HINTON (PROFESSOR AT UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO, CONSIDERED ONE OF THE “GODFATHERS OF AI”)

Humans fly spaceships, split atoms, and edit genes. No other animal has even invented the wheel.

Because of humanity’s larger résumé of inventions, you might think that we would have little to learn from the brains of other animals. You might think that the human brain would be entirely unique and nothing like the brains of other animals, that some special brain structure would be the secret to our cleverness. But this is not what we see.

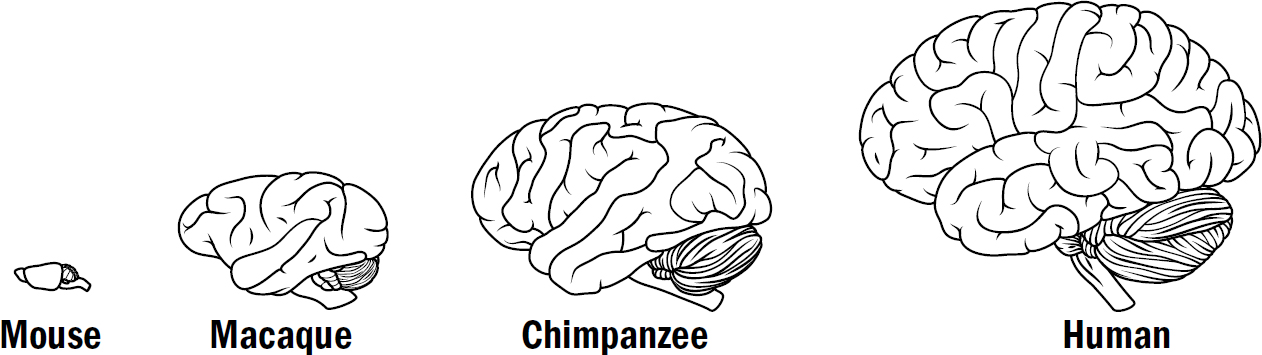

What is most striking when we examine the brains of other animals is how remarkably similar their brains are to our own. The difference between our brain and a chimpanzee’s brain, besides size, is barely anything. The difference between our brain and a rat’s brain is only a handful of brain modifications. The brain of a fish has almost all the same structures as our brain.

These similarities in brains across the animal kingdom mean something important. They are clues. Clues about the nature of intelligence. Clues about ourselves. Clues about our past.

Although today brains are complex, they were not always so. The brain emerged from the unthinking chaotic process of evolution; small random variations in traits were selected for or pruned away depending on whether they supported the further reproduction of the life-form.

If only we could go back in time and examine this first brain to understand how it worked and what tricks it enabled. If only we could then track the complexification forward in the lineage that led to the human brain, observing each physical modification that occurred and the intellectual abilities it afforded. If we could do this, we might be able to grasp the complexity that eventually emerged. Indeed, as the biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky famously said, “Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution.”

Even Darwin fantasized about reconstructing such a story. He ends his Origin of Species fantasizing about a future when “psychology will be based on a new foundation, that of the necessary acquirement of each mental power and capacity by gradation.” One hundred fifty years after Darwin, this may finally be possible.

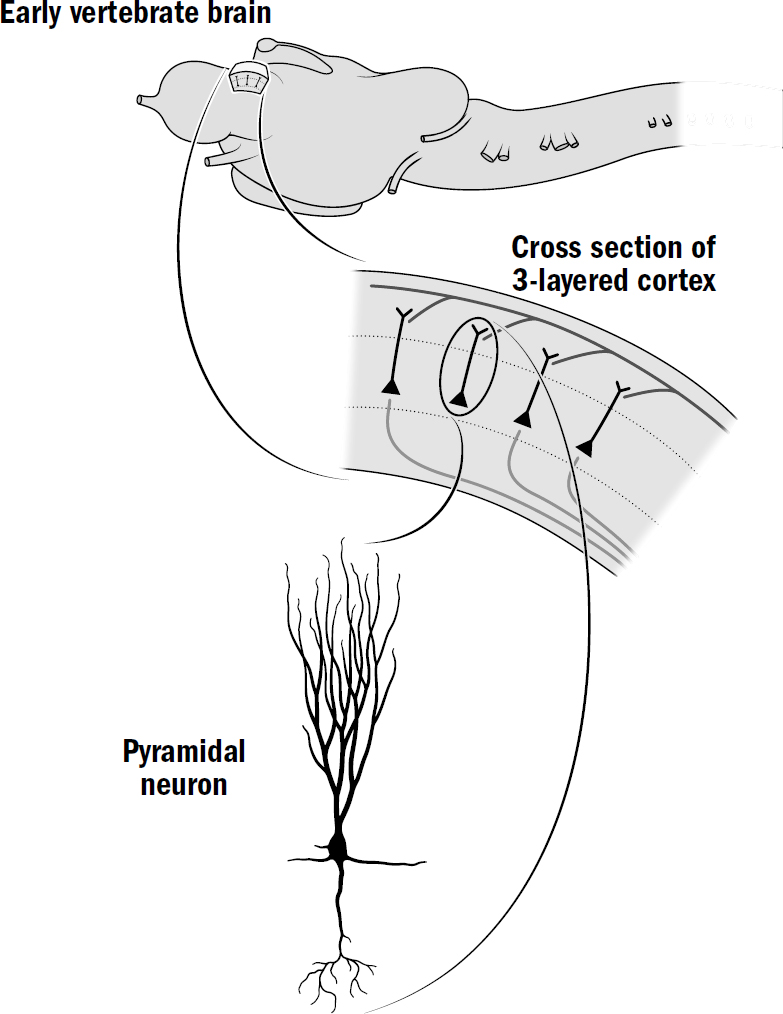

Although we have no time machines, we can, in principle, engage in time travel. In just the past decade, evolutionary neuroscientists have made incredible progress in reconstructing the brains of our ancestors. One way they do this is through the fossil record—scientists can use the fossilized skulls of ancient creatures to reverse-engineer the structure of their brains. Another way to reconstruct the brains of our ancestors is by examining the brains of other animals in the animal kingdom.

The reason why brains across the animal kingdom are so similar is that they all derive from common roots in shared ancestors. Every brain in the animal kingdom is a little clue as to what the brains of our ancestors looked like; each brain is not only a machine but a time capsule filled with hidden hints of the trillions of minds that came before. And by examining the intellectual feats these other animals share and those they do not, we can begin to not only reconstruct the brains of our ancestors, but also determine what intellectual abilities these ancient brains afforded them. Together, we can begin to trace acquirement of each mental power by gradation.

It is all, of course, still a work in progress, but the story is becoming tantalizingly clear.

The Myth of Layers

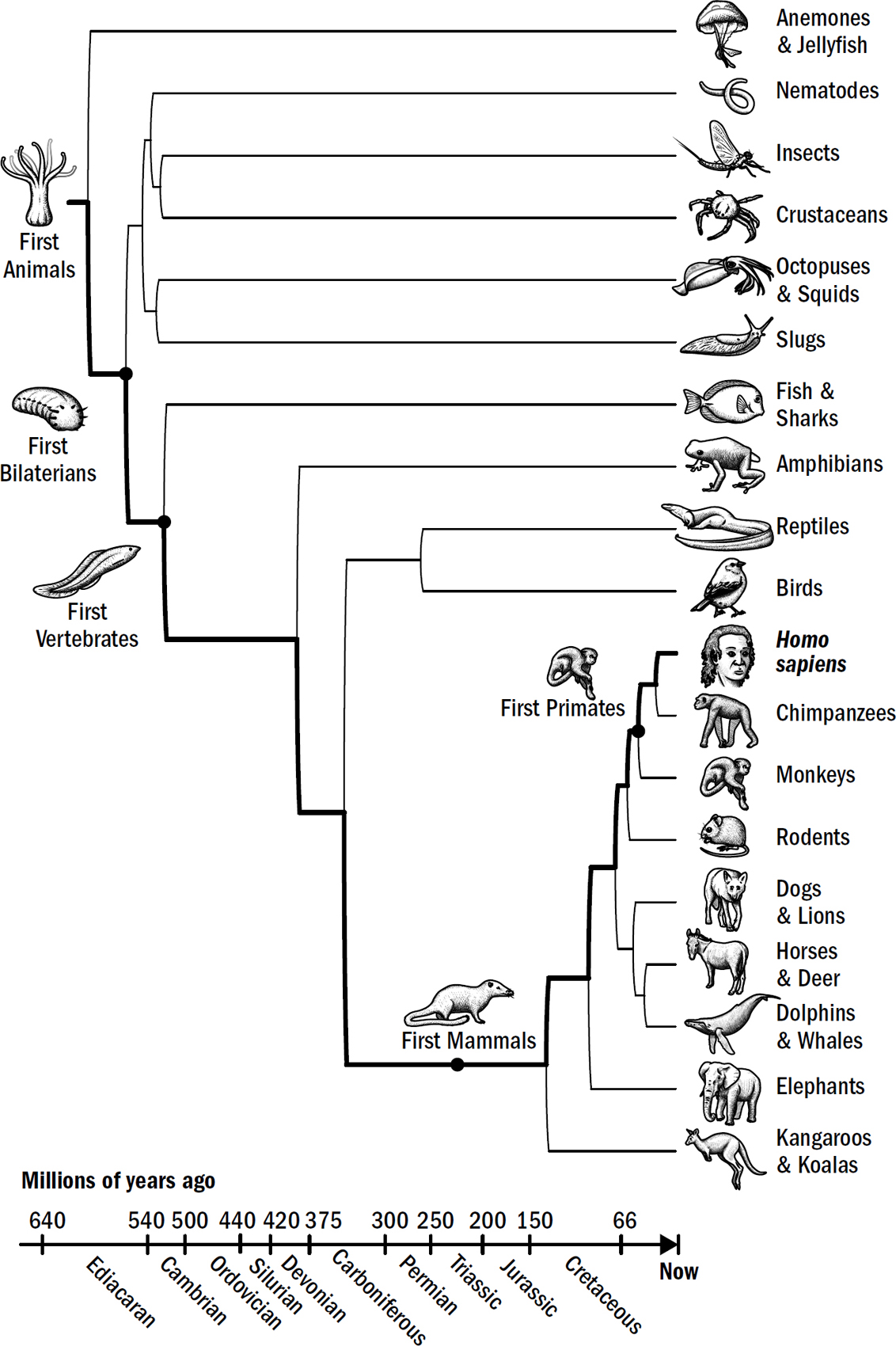

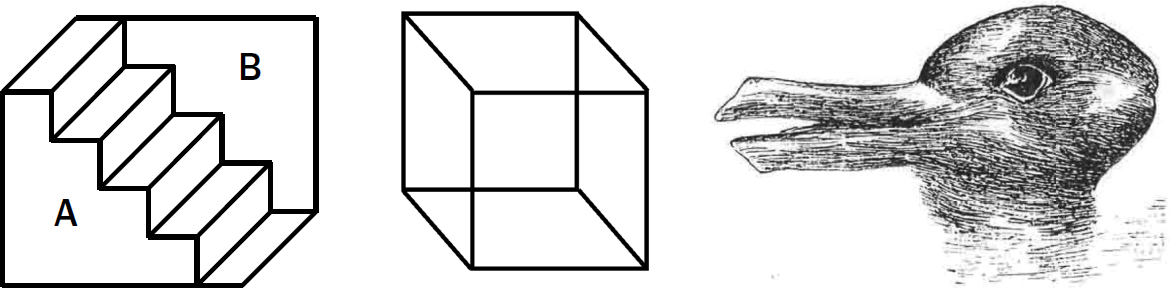

I am hardly the first to propose an evolutionary framework for understanding the human brain. There is a long tradition of such frameworks. The most famous was formulated in the 1960s by the neuroscientist Paul MacLean. MacLean hypothesized that the human brain was made of three layers (hence triune), each built on top of another: the neocortex, which evolved most recently, on top of the limbic system, which evolved earlier, on top of the reptile brain, which evolved first.

MacLean argued that the reptile brain was the center of our basic survival instincts, such as aggression and territoriality. The limbic system was supposedly the center of emotions, such as fear, parental attachment, sexual desire, and hunger. And the neocortex was supposedly the center of cognition, gifting us with language, abstraction, planning, and perception. MacLean’s framework suggested that reptiles had only a reptile brain, mammals like rats and rabbits had a reptile brain and a limbic system, and we humans had all three systems. Indeed, to him, these “three evolutionary formations might be imagined as three interconnected biological computers, with each having its own special intelligence, its own subjectivity, its own sense of time and space, and its own memory,

Figure 1: MacLean’s triune brain

Figure by Max Bennett (inspired by similar figures found in MacLean’s work)

But even if MacLean’s triune brain had turned out to be closer to the truth, its biggest problem is that its functional divisions aren’t particularly useful for our purposes. If our goal is to reverse-engineer the human brain to understand the nature of intelligence, MacLean’s three systems are too broad and the functions attributed to them too vague to provide us with even a point at which to start.

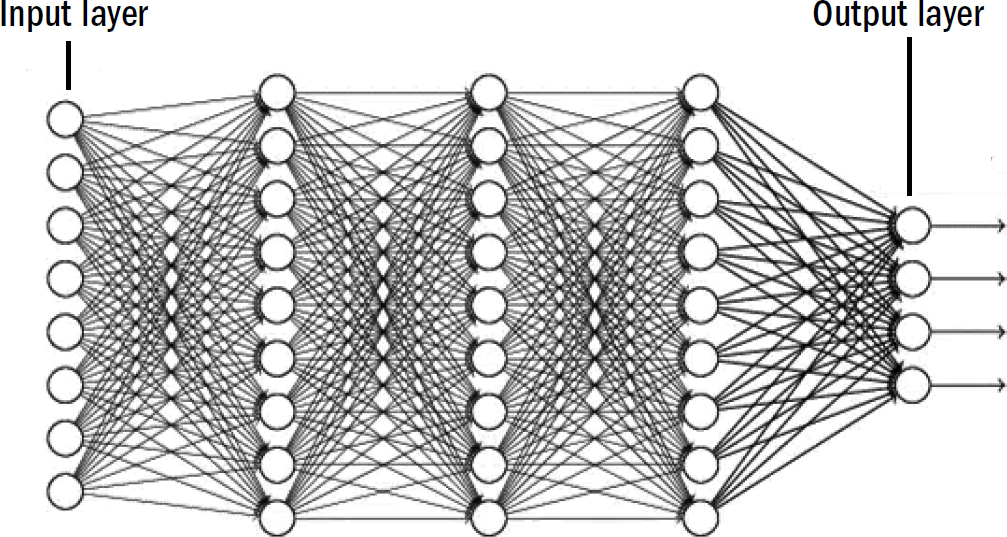

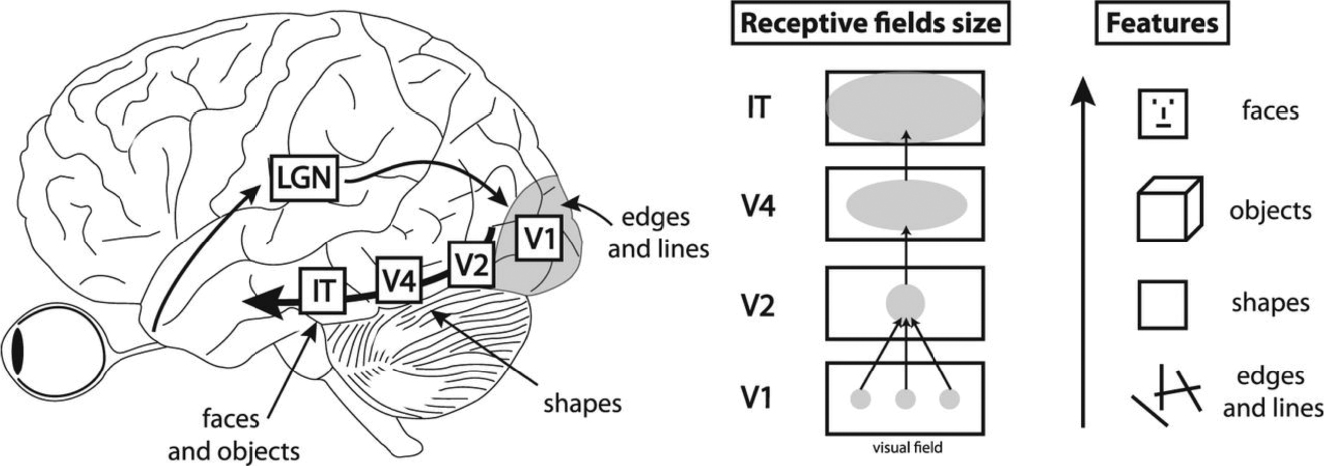

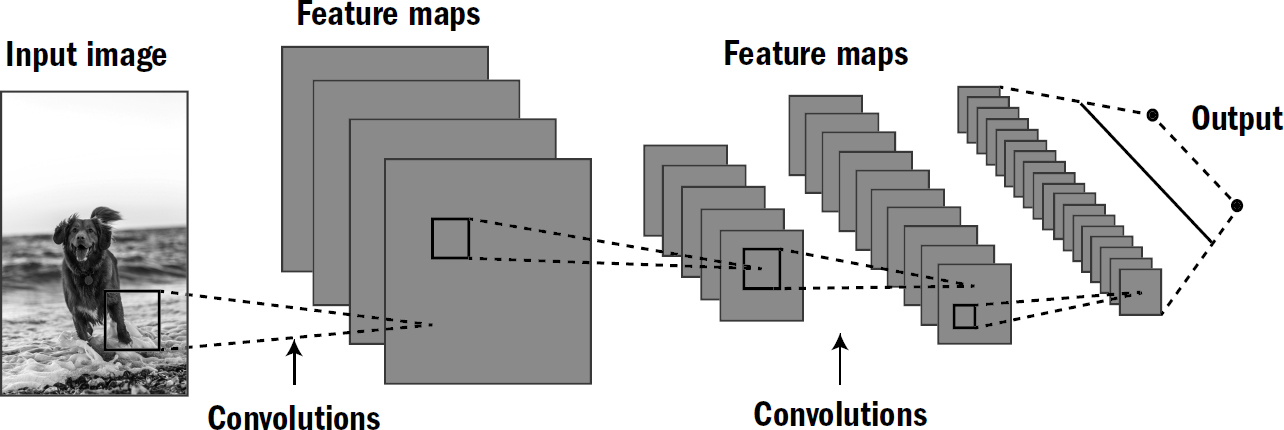

We need to ground our understanding of how the brain works and how it evolved in our understanding of how intelligence works—for which we must look to the field of artificial intelligence. The relationship between AI and the brain goes both ways; while the brain can surely teach us much about how to create artificial humanlike intelligence, AI can also teach us about the brain. If we think some part of the brain uses some specific algorithm but that algorithm doesn’t work when we implement it in machines, this gives us evidence that the brain might not work this way. Conversely, if we find an algorithm that works well in AI systems, and we find parallels between the properties of these algorithms and properties of animal brains, this gives us some evidence that the brain might indeed work this way.

The physicist Richard Feynman left the following on a blackboard shortly before his death: “What I cannot create, I do not understand.” The brain is our guiding inspiration for how to build AI, and AI is our litmus test for how well we understand the brain.

We need a new evolutionary story of the brain, one grounded not only in a modern understanding of how brain anatomy changed over time, but also in a modern understanding of intelligence itself.

The Five Breakthroughs

—YANN LECUN, HEAD OF AI AT META

We have a lot of evolutionary history to cover—four billion years. Instead of chronicling each minor adjustment, we will be chronicling the major evolutionary breakthroughs. In fact, as an initial approximation—a first template of this story—the entirety of the human brain’s evolution can be reasonably summarized as the culmination of only five breakthroughs, starting from the very first brains and going all the way to human brains.

These five breakthroughs are the organizing map to our book, and they make up our itinerary for our adventure back in time. Each breakthrough emerged from new sets of brain modifications and equipped animals with a new portfolio of intellectual abilities. This book is divided into five parts, one for each breakthrough. In each section, I will describe why these abilities evolved, how they worked, and how they still manifest in human brains today.

Each subsequent breakthrough was built on the foundation of those that came before and provided the foundation for those that would follow. Past innovations enabled future innovations. It is through this ordered set of modifications that the evolutionary story of the brain helps us make sense of the complexity that eventually emerged.

But this story cannot be faithfully retold by considering only the biology of our ancestors’ brains. These breakthroughs always emerged from periods when our ancestors faced extreme situations or got caught in powerful feedback loops. It was these pressures that led to rapid reconfigurations of brains. We cannot understand the breakthroughs in brain evolution without also understanding the trials and triumphs of our ancestors: the predators they outwitted, the environmental calamities they endured, and the desperate niches they turned to for survival.

And crucially, we will ground these breakthroughs in what is currently known in the field of AI, for many of these breakthroughs in biological intelligence have parallels to what we have learned in artificial intelligence. Some of these breakthroughs represent intellectual tricks we understand well in AI, while other tricks still lay beyond our understanding. And in this way, perhaps the evolutionary story of the brain can shed light on what breakthroughs we may have missed in the development of artificial humanlike intelligence. Perhaps it will reveal some of nature’s hidden clues.

Me

I wish I could tell you that I wrote this book because I have spent my whole life pondering the evolution of the brain and trying to build intelligent robots. But I am not a neuroscientist or a roboticist or even a scientist. I wrote this book because I wanted to read this book.

I came to the perplexing discrepancy between human and artificial intelligence by trying to apply AI systems to real-world problems. I spent the bulk of my career at a company I cofounded named Bluecore; we built software and AI systems to help some of the largest brands in the world personalize their marketing. Our software helped predict what consumers would buy before they knew what they wanted. We were merely one tiny part in a sea of countless companies beginning to use the new advances in AI systems. But all these many projects, both big and small, were shaped by the same perplexing questions.

When commercializing AI systems, there is eventually a series of meetings between business teams and machine learning teams. The business teams look for applications of new AI systems that would be valuable, while only the machine learning teams understand what applications would be feasible. These meetings often reveal our mistaken intuitions about how much we understand about intelligence. Businesspeople probe for applications of AI systems that seem straightforward to them. But frequently, these tasks seem straightforward only because they are straightforward for our brains. Machine learning people then patiently explain to the business team why the idea that seems simple is, in fact, astronomically difficult. And these debates go back and forth with every new project. It was from these explorations into how far we could stretch modern AI systems and the surprising places where they fall short that I developed my original curiosity about the brain.

Of course, I am also a human and I, like you, have a human brain. So it was easy for me to become fascinated with the organ that defines so much of the human experience. The brain offers answers not only about the nature of intelligence, but also why we behave the way we do. Why do we frequently make irrational and self-defeating choices? Why does our species have such a long recurring history of both inspiring selflessness and unfathomable cruelty?

My personal project began with merely trying to read books to answer my own questions. This eventually escalated to lengthy email correspondences with neuroscientists who were generous enough to indulge the curiosities of an outsider. This research and these correspondences eventually led me to publish several research papers, which all culminated in the decision to take time off work to turn these brewing ideas into a book.

Throughout this process, the deeper I went, the more I became convinced that there was a worthwhile synthesis to be contributed, one that could provide an accessible introduction to how the brain works, why it works the way it does, and how it overlaps and differs from modern AI systems; one that could bring various ideas across neuroscience and AI together under an umbrella of a single story.

A Brief History of Intelligence is a synthesis of the work of many others. At its heart, it is merely an attempt to put together the pieces that were already there. I have done my best to give due credit throughout the book, always aiming to celebrate those scientists who did the actual research. Anywhere I have failed to do so is unintentional. Admittedly, I couldn’t resist sprinkling in a few speculations of my own, but I will aim to be clear when I step into such territory.

It is perhaps fitting that the origin of this book, like the origin of the brain itself, came not from prior planning but from a chaotic process of false starts and wrong turns, from chance, iteration, and lucky circumstance.

A Final Point (About Ladders and Chauvinism)

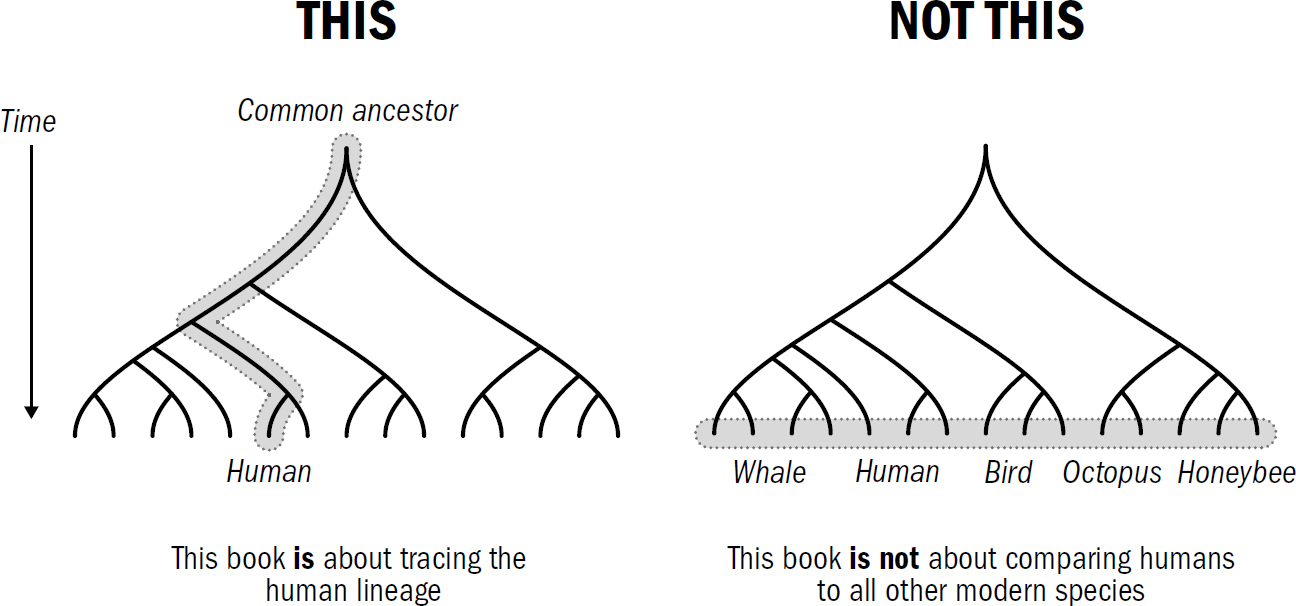

I have one final point to make before we begin our journey back in time. There is a misinterpretation that will loom dangerously between the lines of this entire story.

This book will draw many comparisons between the abilities of humans and those of other animals alive today, but this is always done by picking specifically those animals that are believed to be most similar to our ancestors. This entire book—the five-breakthroughs framework itself—is solely the story of the human lineage, the story of how our brains came to be; one could just as easily construct a story of how the octopus or honeybee brain came to be, and it would have its own twists and turns and its own breakthroughs.

Just because our brains wield more intellectual abilities than those of our ancestors does not mean that the modern human brain is strictly intellectually superior to those of other modern animals.

Evolution independently converges on common solutions all the time. The innovation of wings independently evolved in insects, bats, and birds; the common ancestor of these creatures did not have wings. Eyes are also believed to have independently evolved many times. Thus, when I argue that an intellectual ability, such as episodic memory, evolved in early mammals, this does not mean that today only mammals have episodic memory. Like with wings and eyes, other lineages of life may have independently evolved episodic memory. Indeed, many of the intellectual faculties that we will chronicle in this book are not unique to our lineage, but have independently sprouted along numerous branches of earth’s evolutionary tree.

Since the days of Aristotle, scientists and philosophers have constructed what modern biologists refer to as a “scale of nature” (or, since scientists like using Latin terms, scala naturae). Aristotle created a hierarchy of all life-forms with humans being superior to other mammals, who were in turn superior to reptiles and fish, who were in turn superior to insects, who were in turn superior to plants.

Figure 2

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

Even after the discovery of evolution, the idea of a scale of nature continues to persist. This idea that there is a hierarchy of species is dead wrong. All species alive today are, well, alive; their ancestors survived the last 3.5 billion years of evolution. And thus, in that sense—the only sense that evolution cares about—all life-forms alive today are tied for first place.

Species fall into different survival niches, each of which optimizes for different things. Many niches—in fact, most niches—are better served by smaller and simpler brains (or no brains at all). Big-brained apes are the result of a different survival strategy than that of worms, bacteria, or butterflies. But none are “better.” In the eyes of evolution, the hierarchy has only two rungs: on one, there are those that survived, and on the other, those that did not.

My appeal: As we trace our story, we must avoid thinking that the complexification from past to future suggests that modern humans are strictly superior to modern animals. We must avoid the accidental construction of a scala naturae. All animals alive today have been undergoing evolution for the same amount of time.

However, there are, of course, things that make us humans unique, and because we are human, it makes sense that we hold a special interest in understanding ourselves, and it makes sense that we strive to make artificial humanlike intelligences. So I hope we can engage in a human-centered story without devolving into human chauvinism. There is an equally valid story to be told for any other animal, from honeybees to parrots to octopuses, with which we share our planet. But we will not tell these stories here. This book tells the story of only one of these intelligences: it tells the story of us.

1

The World Before Brains

LIFE EXISTED ON Earth for a long time—and I mean a long time, over three billion years—before the first brain made an appearance. By the time the first brains evolved, life had already persevered through countless evolutionary cycles of challenge and change. In the grand arc of life on Earth, the story of brains would not be found in the main chapters but in the epilogue—brains appeared only in the most recent 15 percent of life’s story. Intelligence too existed for a long time before brains; as we will see, life began exhibiting intelligent behavior early in its story. We cannot understand why and how brains evolved without first reviewing the evolution of intelligence itself.

Around four billion years ago, deep in the volcanic oceans of a lifeless Earth, just the right soup of molecules were bouncing around the microscopic nooks and crannies of

Although these self-replicating DNA-like molecules also succumbed to the destructive effects of entropy, they didn’t have to survive individually to survive collectively—as long as they endured long enough to create their own copies, they would, in essence, persist. This is the genius of self-replication. With these first self-replicating molecules, a primitive version of the process of evolution began; any new lucky circumstances that facilitated more successful duplication would, of course, lead to more duplicates.

There were two subsequent evolutionary transformations that led to life. The first was when protective lipid bubbles entrapped these DNA molecules using the same mechanism by which soap, also made of lipids, naturally bubbles when you wash your hands. These DNA-filled microscopic lipid bubbles were the first versions of cells, the fundamental unit of life.

The second evolutionary transformation occurred when a suite of nucleotide-based molecules—ribosomes—began translating specific sequences of DNA into specific sequences of amino acids that were then folded into specific three-dimensional structures we call proteins. Once produced, these proteins float around inside a cell or are embedded in the wall of the cell fulfilling different functions. You have probably, at least in passing, heard that your DNA is made up of genes. Well, a gene is simply the section of DNA that codes for the construction of a specific and singular protein. This was the invention of protein synthesis, and it is here that the first sparks of intelligence made their appearance.

DNA is relatively inert, effective for self-duplication but otherwise limited in its ability to manipulate the microscopic world around it. Proteins, however, are far more flexible and powerful. In many ways, proteins are more machine than molecule. Proteins can be constructed and folded into many shapes—sporting tunnels, latches, and other robotic moving parts—and can thereby subserve endless cellular functions, including “intelligence.”

Armed with proteins for movement and perception, early life could monitor and respond to the outside world. Bacteria can swim away from environments that lower the probability of successful replication, environments that have, for example, temperatures that are too hot or cold or chemicals that are destructive to DNA or cell membranes. Bacteria can also swim toward environments that are amenable to reproduction.

And in this way, these ancient cells indeed had a primitive version of intelligence, implemented not in neurons but in a complex network of chemical cascades and proteins.

The development of protein synthesis not only begot the seeds of intelligence but also transformed DNA from mere matter to a medium for storing information. Instead of being the self-replicating stuff of life itself, DNA was transformed into the informational foundation from which the stuff of life is constructed. DNA had officially become life’s blueprint, ribosomes its factory, and proteins its product.

With these foundations in place, the process of evolution was initiated in full force: variations in DNA led to variations in proteins, which led to the evolutionary exploration of new cellular machinery, which, through natural selection, were pruned and selected for based on whether they further supported survival. By this point in life’s story, we have concluded the long, yet-to-be-replicated, and mysterious process scientists call abiogenesis: the process by which nonbiological matter (abio) is converted into life (genesis).

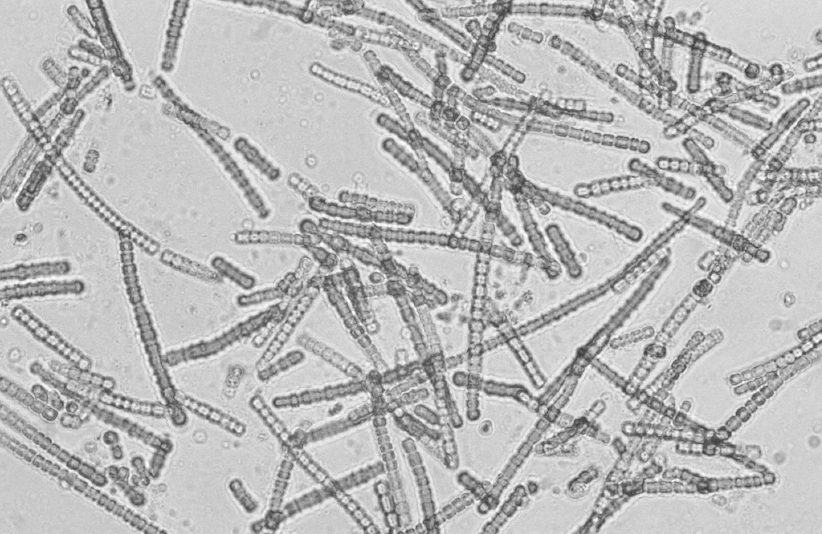

The Terraforming of Earth

LUCA, living around 3.5 billion years ago, likely resembled a simpler version of a modern bacteria. And indeed, for a long time after this, all life was bacterial. After a further billion years—through trillions upon trillions of evolutionary iterations—Earth’s oceans were brimming with many diverse species of these microbes, each with its own portfolio of DNA and proteins. One way in which these early microbes differed from one another was in their systems of energy production. The story of life, at its core, is as much about energy as it is about entropy.

Photograph by Willem van Aken on March 18, 1993. Figure from www.scienceimage.csiro.au/image/4203 CC BY 3.0 license.

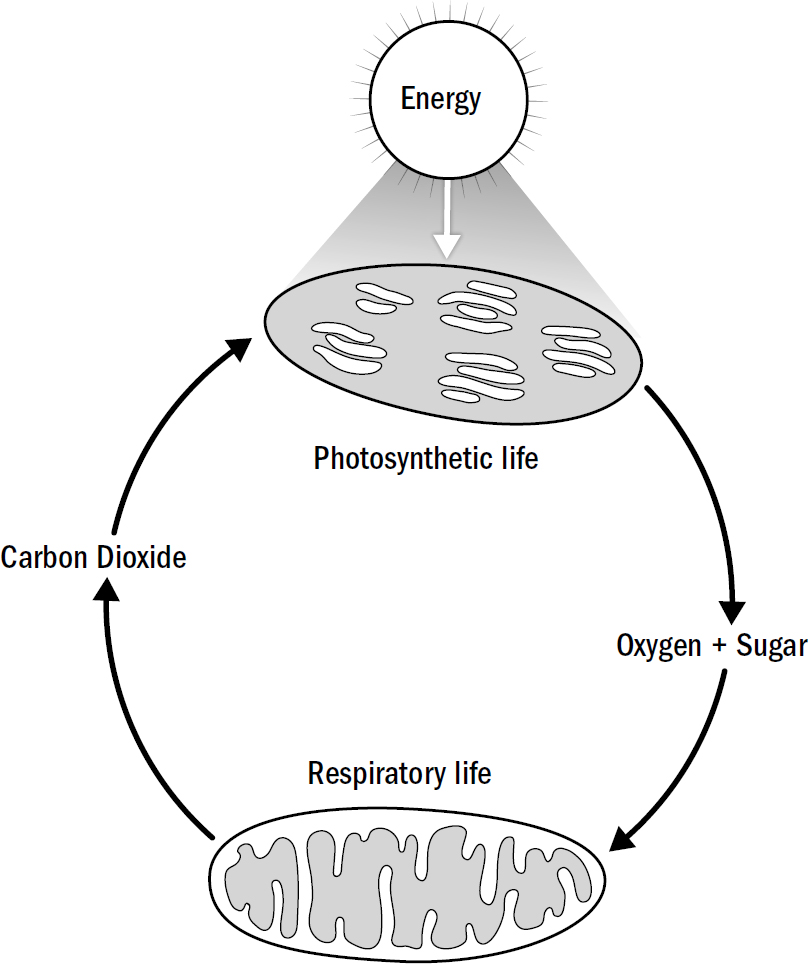

Life on Earth fell into perhaps the greatest symbiosis ever found between two competing but complementary systems of life, one that lasts to this day. One category of life was photosynthetic, converting water and carbon dioxide into sugar and oxygen. The other was respiratory, converting sugar and oxygen back into carbon dioxide. At the time, these two forms of life were similar, both single-celled bacteria. Today this symbiosis is made up of very different forms of life. Trees, grass, and other plants are some of our modern photosynthesizers, while fungi and animals are some of our modern respirators.

Figure 1.2: The symbiosis between photosynthetic and respiratory life

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

Cellular respiration requires sugar to produce energy, and this basic need provided the energetic foundation for the eventual intelligence explosion that occurred uniquely within the descendants of respiratory life. While most, if not all, microbes at the time exhibited primitive levels of intelligence, it was only in respiratory life that intelligence was later elaborated and extended. Respiratory microbes differed in one crucial way from their photosynthetic cousins: they needed to hunt. And hunting required a whole new degree of smarts.

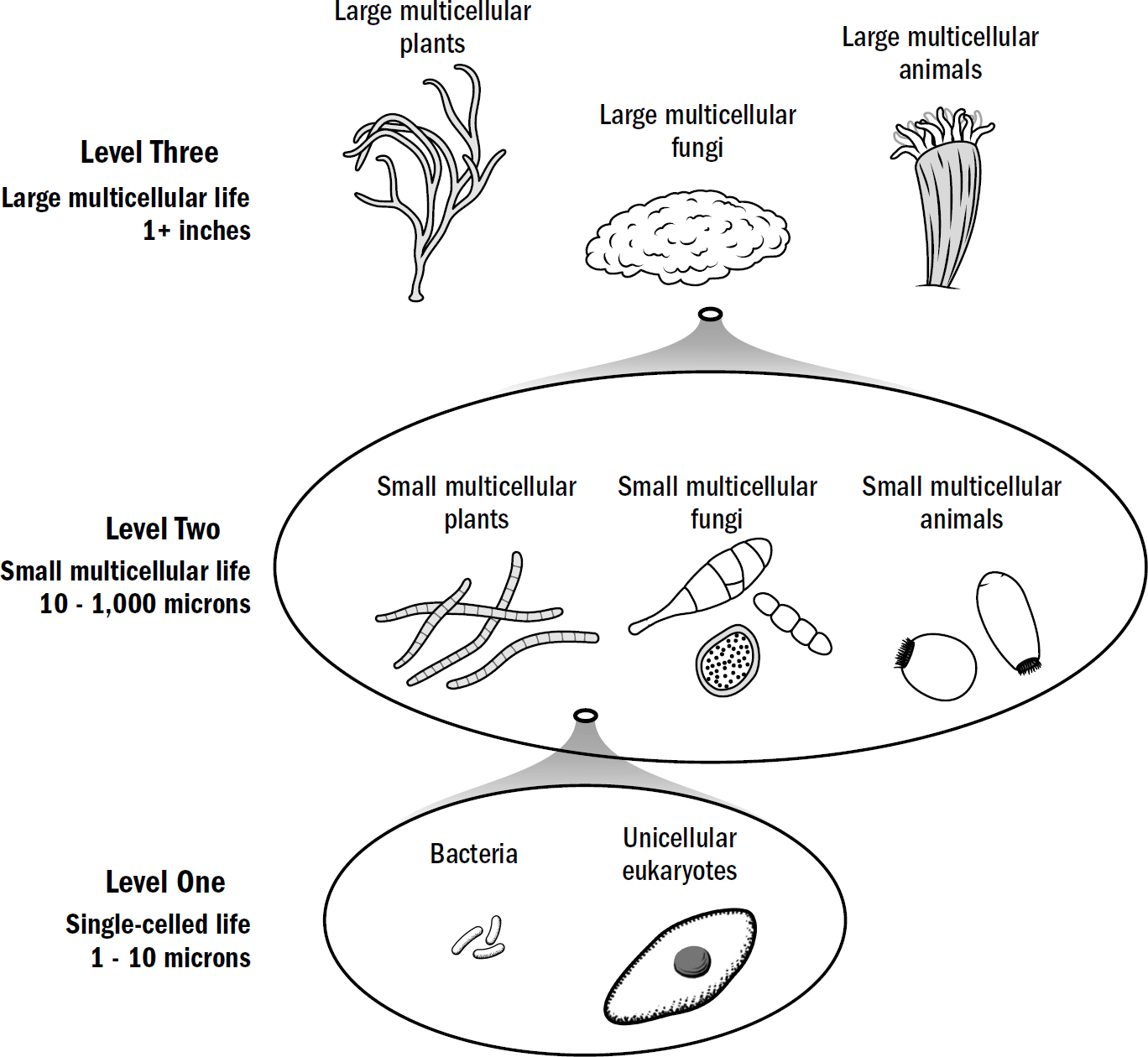

Three Levels

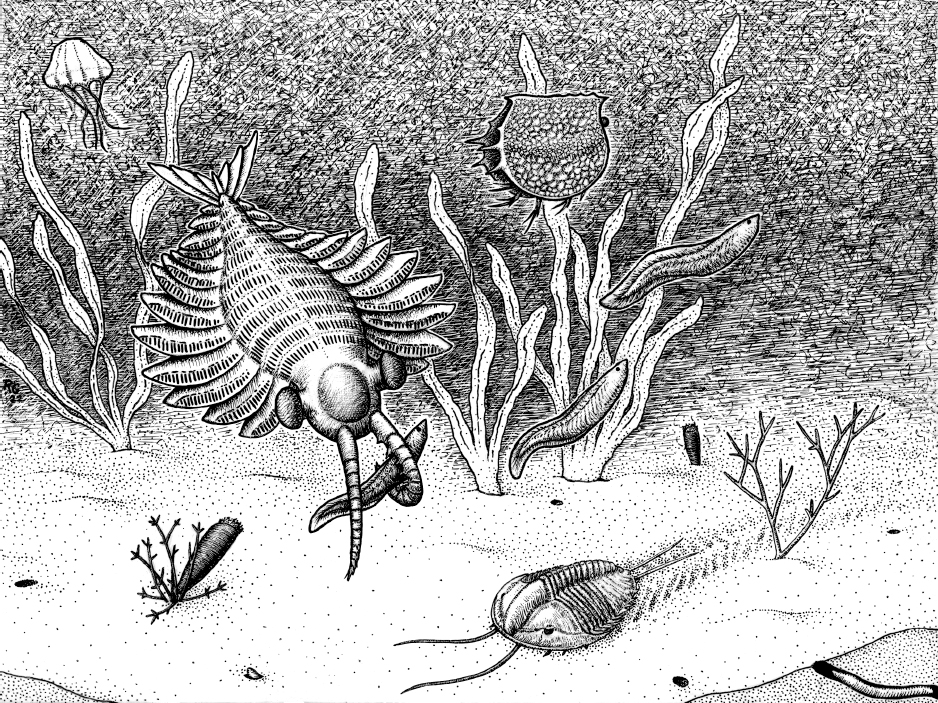

However, unlike the cells that came before, respiratory life could survive only by stealing the energetic prize—the sugary innards—of photosynthetic life. Thus, the world’s utopic peace ended quite abruptly with the arrival of aerobic respiration. It was here that microbes began to actively eat other microbes. This fueled the engine of evolutionary progress; for every defensive innovation prey evolved to stave off being killed, predators evolved an offensive innovation to overcome that same defense. Life became caught in an arms race, a perpetual feedback loop: offensive innovations led to defensive innovations that required further offensive innovations.

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

What was common across these eukaryote lineages was that all three—plants, fungi, and animals—each independently evolved multicellularity. Most of what you see and think of as life—humans, trees, mushrooms—are primarily multicellular organisms, cacophonies of billions of individual cells all working together to create a singular emergent organism. A human is made up of exactly such diverse types of specialized cells: skin cells, muscle cells, liver cells, bone cells, immune cells, blood cells. A plant has specialized cells too. These cells all serve different functions while still serving a common purpose: supporting the survival of the overall organism.

Figure 1.4: Three complexity levels in the ancient sea before brains

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

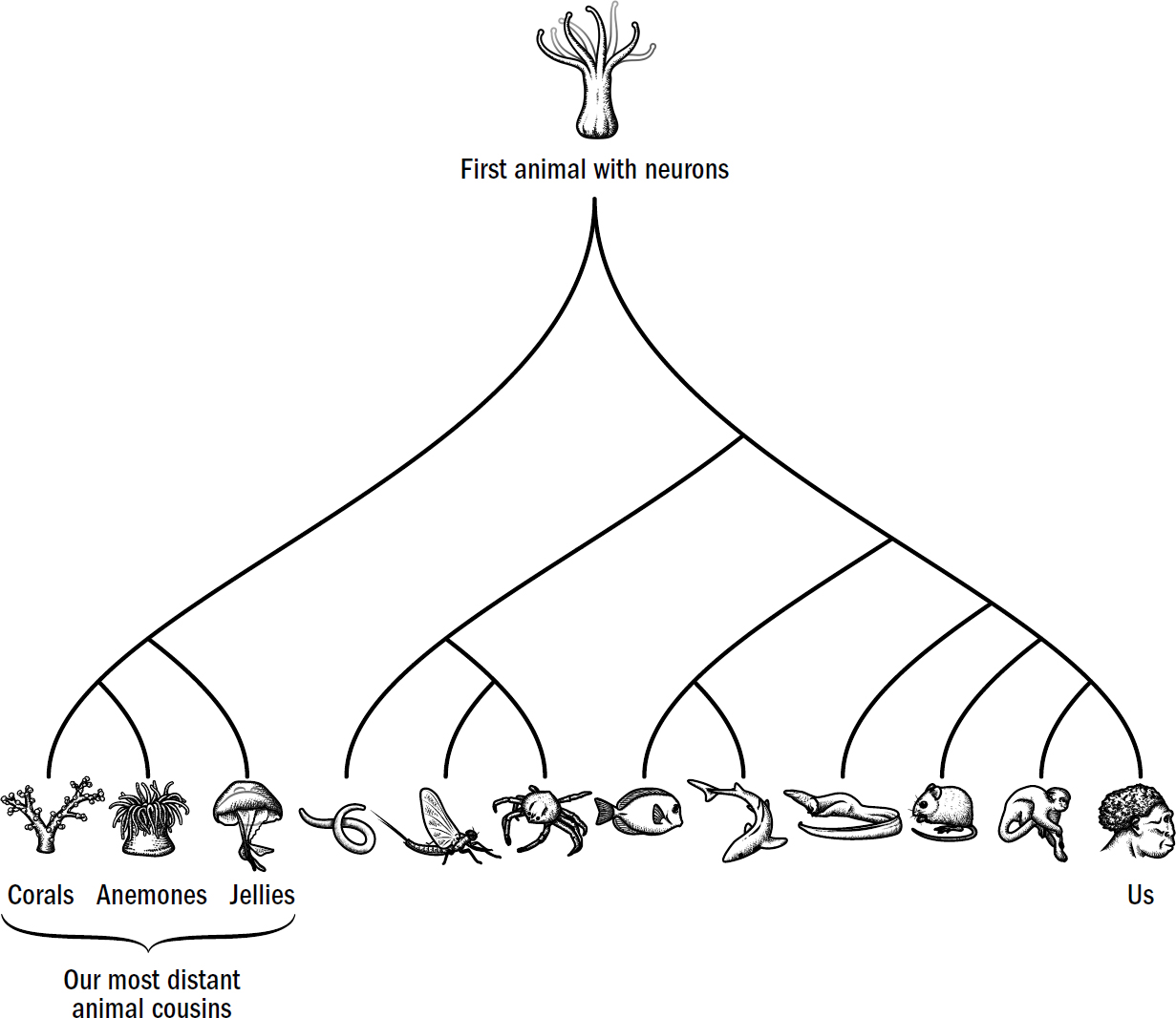

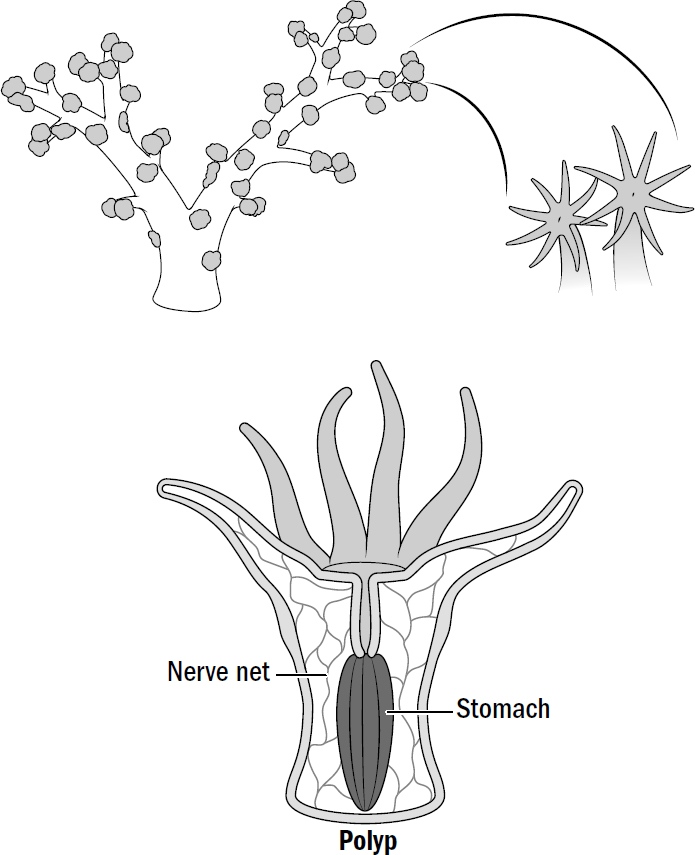

These early animals probably wouldn’t resemble what you think of as animals. But they contained something that made them different from all other life at the time: neurons.

The Neuron

What a neuron is and what it does depends on whom you ask. If you ask a biologist, neurons are the primary cells that make up the nervous system. If you ask a machine learning researcher, neurons are the fundamental units of neural networks, little accumulators that perform the basic task of computing a weighted summation of their inputs. If you ask a psychophysicist, neurons are the sensors that measure features of the external world. If you ask a neuroscientist specializing in motor control, neurons are effectors, the controllers of muscles and movement. If you ask other people, you might get a wide range of answers, from “Neurons are little electrical wires in your head” to “Neurons are the stuff of consciousness.” All of these answers are right, carrying a kernel of the whole truth, but incomplete on their own.

The nervous systems of all animals—from worms to wombats—are made up of these stringy odd-shaped cells called neurons. There is an incredible diversity of neurons, but despite this diversity in shapes and sizes, all neurons work the same way. This is the most shocking observation when comparing neurons across species—they are all, for the most part, fundamentally identical. The neurons in the human brain operate the same way as the neurons in a jellyfish. What separates you from an earthworm is not the unit of intelligence itself—neurons—but how these units are wired together.

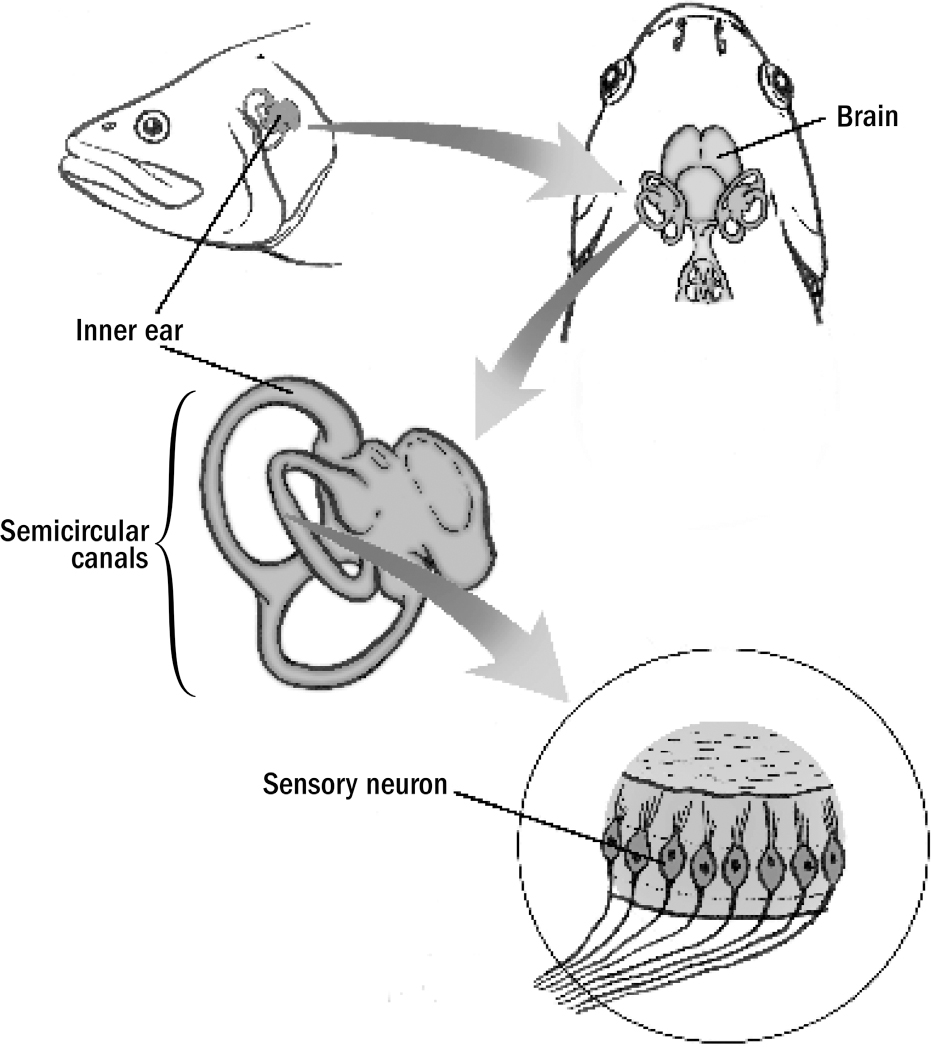

Figure from Reichert, 1990. Used with permission.

Why Fungi Don’t Have Neurons but Animals Do

You aren’t all that different from mold. Despite their appearance, fungi have more in common with animals than they do with plants. While plants survive by photosynthesis, animals and fungi both survive by respiration. Animals and fungi both breathe oxygen and eat sugar; both digest their food, breaking cells down using enzymes and absorbing their inner nutrients; and both share a much more recent common ancestor than either do with plants, which diverged much earlier. At the dawn of multicellularity, fungi and animal life would have been extremely similar. And yet one lineage (animals) went on to evolve neurons and brains, and the other (fungi) did not. Why?

Fungi produce trillions of single-celled spores that float around dormant. If by luck one happens to find itself near dying life, it will blossom into a large fungal structure, growing hairy filaments into the decaying tissue, secreting enzymes, and absorbing the released nutrients. This is why mold always shows up in old food. Fungal spores are all around us, patiently waiting for something to die. Fungi are currently, and likely have always been, Earth’s garbage collectors.

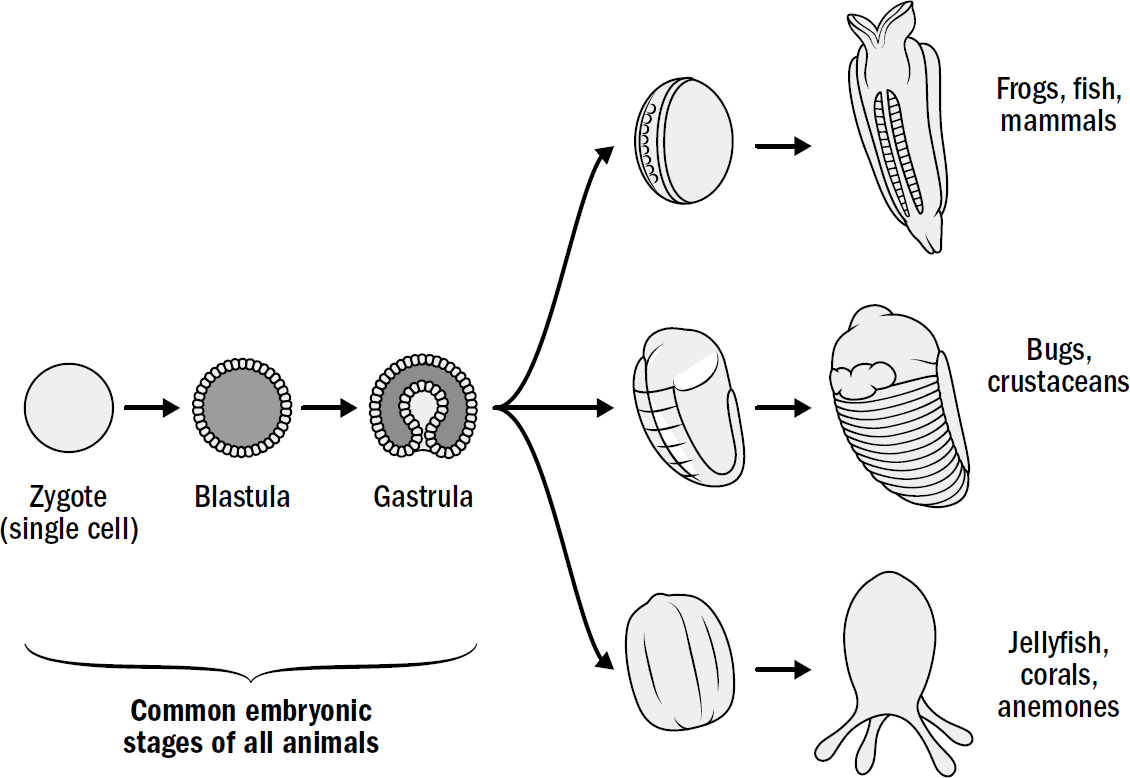

In fact, the formation of an inner cavity for digestion may have been the defining feature of these early animals. Practically every animal alive today develops in the same three initial steps. From a single-celled fertilized egg, a hollow sphere (a blastula) forms; this then folds inward to make a cavity, a little “stomach” (a gastrula). This is true of human embryos

Figure 1.6: Shared developmental stages for all animals

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

Figure 1.7: Tree of neuron-enabled animals

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

This coral reflex was not the first or the only way in which multicellular life sensed and responded to the world. Plants and fungi do this just fine without neurons or muscles; plants can orient their leaves toward the sun, and fungi can orient their growth in the direction of food. But still, in the ancient sea at the dawn of multicellularity, this reflex would have been revolutionary, not because it was the first time multicellular life sensed or moved but because it was the first time it sensed and moved with speed and specificity. The movement of plants and fungi takes hours to days; the movement of coral takes seconds.* The movement of plants and fungi is clumsy and inexact; the movement of coral is comparatively very specific—the grasping of prey, opening of the mouth, pulling into the stomach, and closing of the mouth all require a well-timed and accurate orchestration of relaxing some muscles while contracting others. And this is why fungi don’t have neurons and animals do. Although both are large multicellular organisms that feed on other life, only the animal-survival strategy of killing level-two multicellular life requires fast and specific reflexes.* The original purpose of neurons and muscles may have been the simple and inglorious task of swallowing.

Figure 1.8: Soft coral as a model for early animal life

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

Edgar Adrian’s Three Discoveries and the Universal Features of Neurons

The scientific journey by which we have come to understand how neurons work has been long and full of

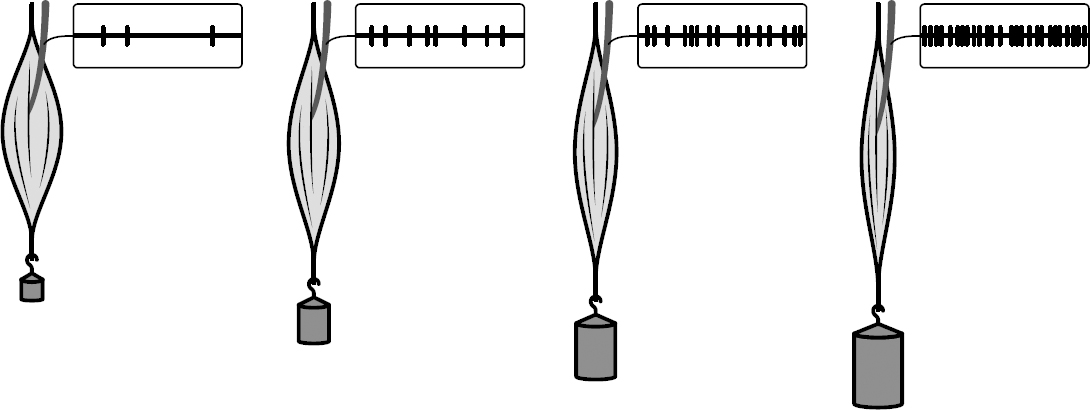

Adrian took a muscle from the neck of a deceased frog and attached a recording device to a single stretch-sensing neuron in the muscle. Such neurons have receptors that are stimulated when muscles are stretched. Adrian then attached various weights to the muscle. The question was: How would the responses of these stretch-sensing neurons change based on the weight placed on the muscle?

Figure 1.9: Adrian charted the relationship between weight and the number of spikes per second (i.e., the spike rate, or firing rate) elicited in these stretch neurons.

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

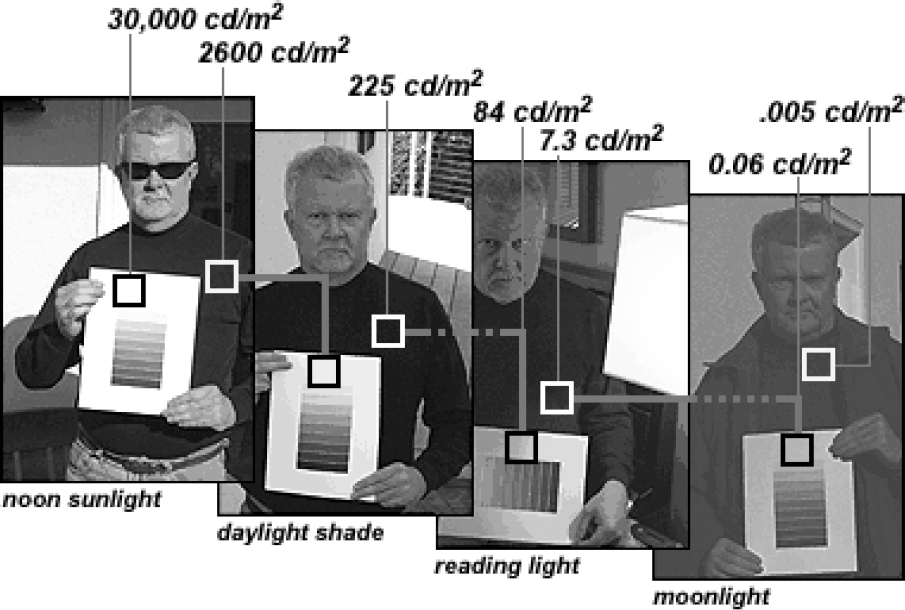

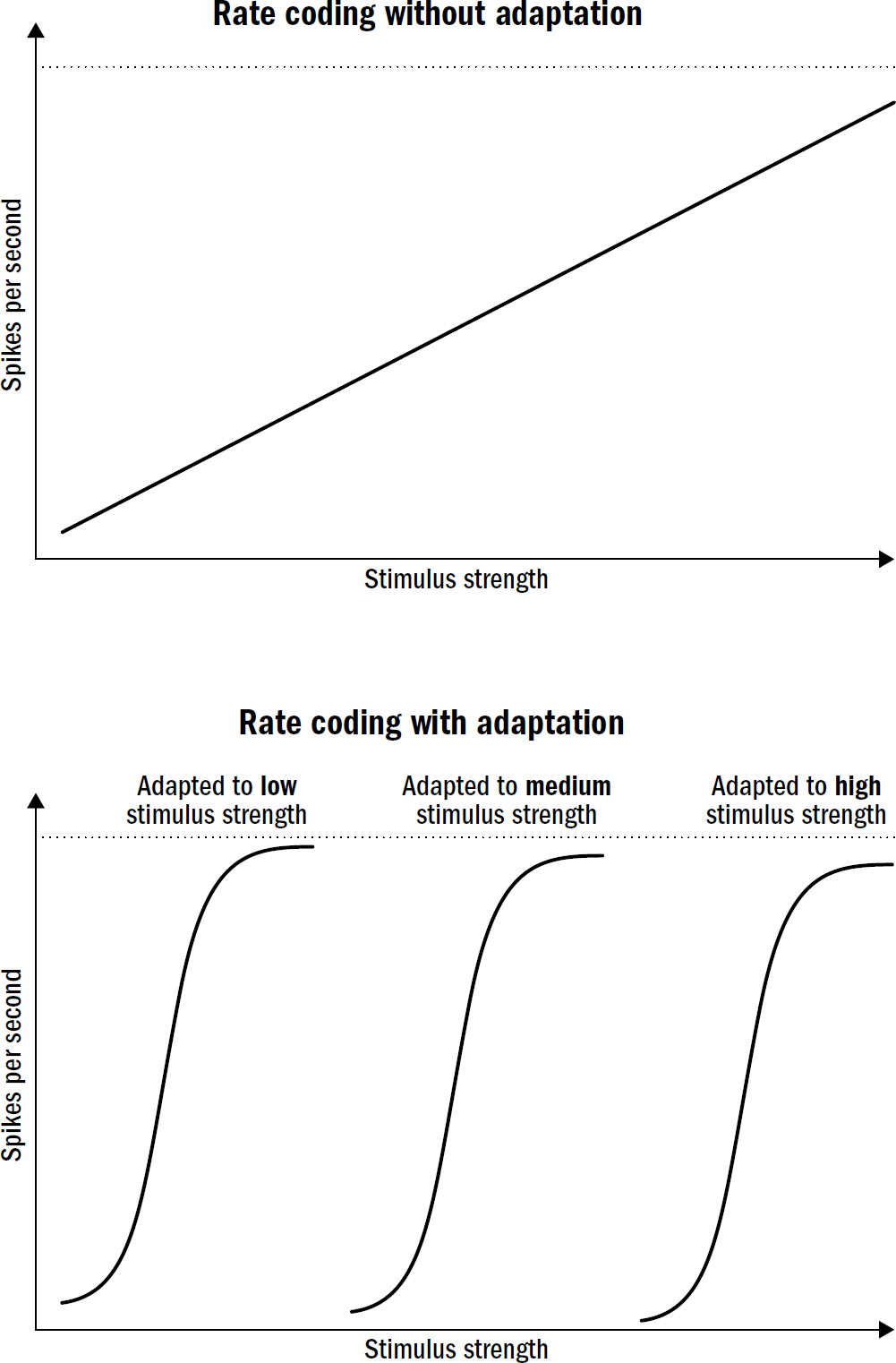

Adrian’s third discovery was the most surprising of all. There is a problem with trying to translate natural variables, such as the pressure of touch or the brightness of light into this language of rate codes. The problem is this: these natural variables have a massively larger range than can be encoded in the firing rate of a neuron.

Figure made by B. MacEvoy, 2015. Used with permission (personal correspondence).

This makes rate coding, on its own, untenable. Neurons simply cannot directly encode such a wide range of natural variables in such a small range of firing rates without losing a huge amount of precision. The resulting imprecision would make it impossible to read inside, detect subtle smells, or notice a soft touch.

It turns out that neurons have a clever solution to this problem. Neurons do not have a fixed relationship between natural variables and firing rates. Instead, neurons are always adapting their firing rates to their environment; they are constantly remapping the relationship between variables in the natural world and the language of firing rates. The term neuroscientists use to describe this observation is adaptation; this was Adrian’s third discovery.

In Adrian’s frog muscle experiments, a neuron might fire one hundred spikes in response to a certain weight. But after this first exposure, the neuron quickly adapts; if you apply the same weight shortly after, it might elicit only eighty spikes. And as you keep doing this, the number of spikes continues to decline. This applies in many neurons throughout the brains of animals—the stronger the stimuli, the greater the change in the neural threshold for spiking. In some sense, neurons are more a measurement of relative changes in stimulus strengths, signaling how much the strength of a stimulus changed relative to its baseline as opposed to signaling the absolute value of the stimulus.

Figure 1.11

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

Here’s the beauty: Adaptation solves the squishing problem. Adaptation enables neurons to precisely encode a broad range of stimulus strengths despite a limited range of firing rates. The stronger a stimulus is, the more strength will be required to get the neuron to respond similarly next time. The weaker a stimulus is, the more sensitive neurons become.

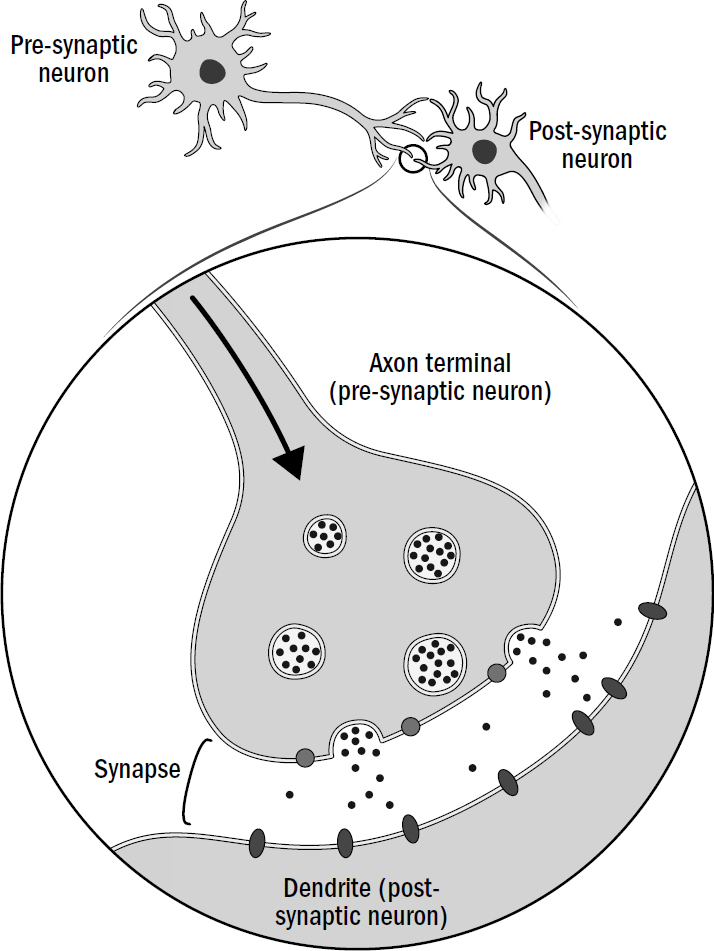

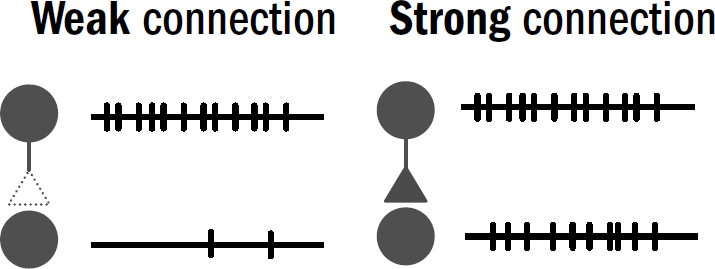

In the 1950s, John Eccles discovered that neurons come in two main varieties: excitatory neurons and inhibitory neurons. Excitatory neurons release neurotransmitters that excite neurons they connect to, while inhibitory neurons release neurotransmitters that inhibit neurons they connect to. In other words, excitatory neurons trigger spikes in other neurons, while inhibitory neurons suppress spikes in other neurons.

Figure 1.12

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

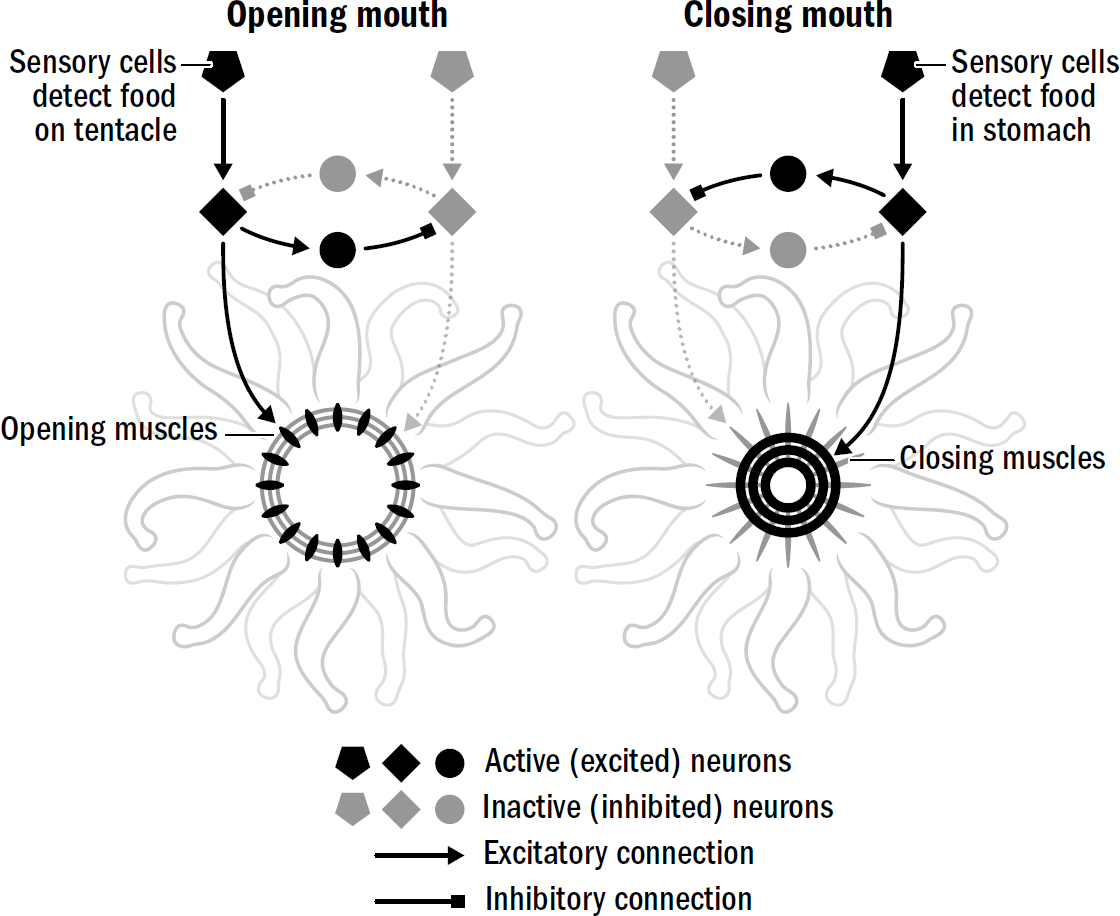

These features of neurons—all-or-nothing spikes, rate coding, adaptation, and chemical synapses with excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters—are universal across all animals, even in animals that have no brain, such as coral polyps and jellyfish. Why do all neurons share these features? If early animals were, in fact, like today’s corals and anemones, then these aspects of neurons enabled ancient animals to successfully respond to their environment with speed and specificity, something that had become necessary to actively capture and kill level-two multicellular life. All-or-nothing electrical spikes triggered rapid and orchestrated reflexive movements so animals could catch prey in response to even the subtlest of touches or smells. Rate coding enabled animals to modify their responses based on the strengths of a touch or smell. Adaptation enabled animals to adjust the sensory threshold for when spikes are generated, allowing them to be highly sensitive to even the subtlest of touches or smells while also preventing overstimulation at higher strengths of stimuli.

What about inhibitory neurons? Why did they evolve? Consider the simple task of a coral polyp opening or closing its mouth. For its mouth to open, one set of muscles must contract

Figure 1.13: The first neural circuit

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

While the first animals, whether gastrula-like or polyp-like creatures, clearly had neurons, they had no brain. Like today’s coral polyps and jellyfish, their nervous system was what scientists call a nerve net: a distributed web of independent neural circuits implementing their own independent reflexes.

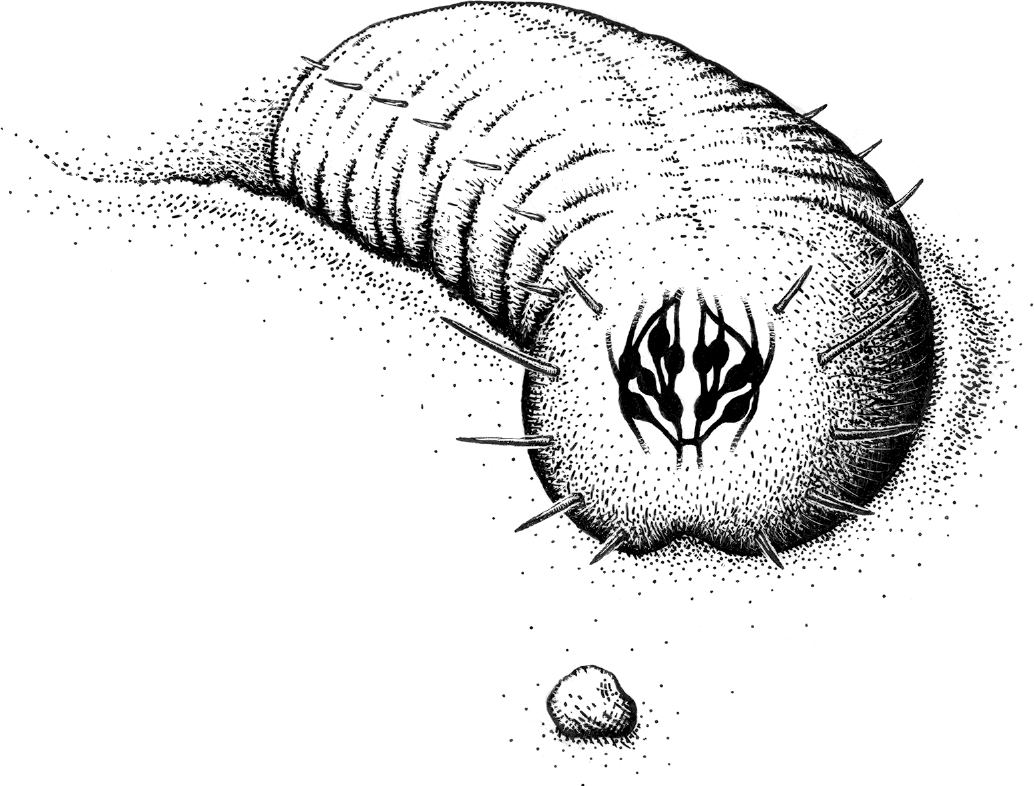

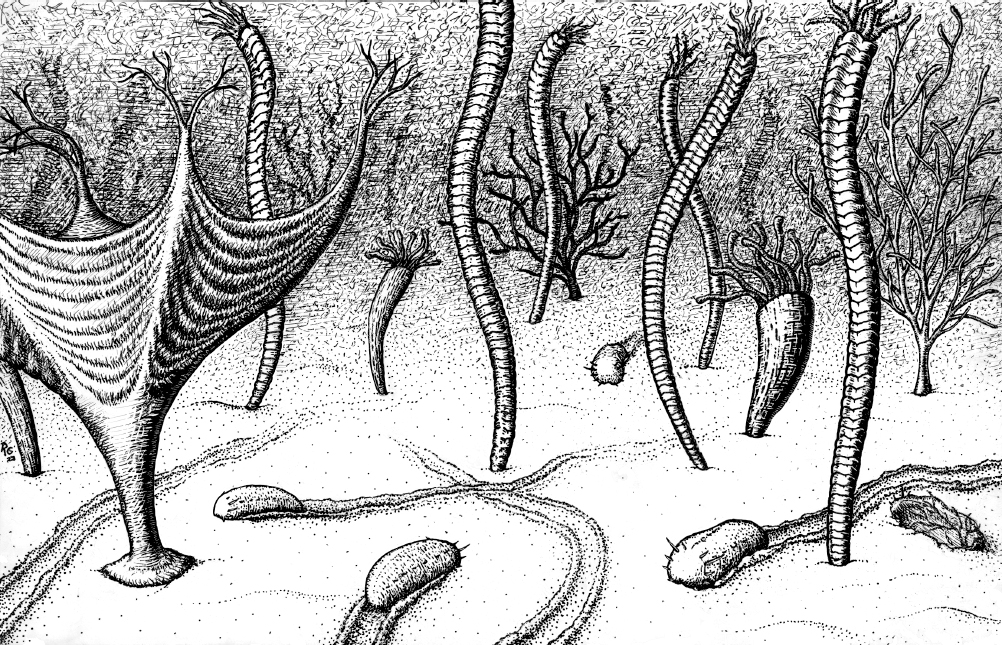

Breakthrough #1

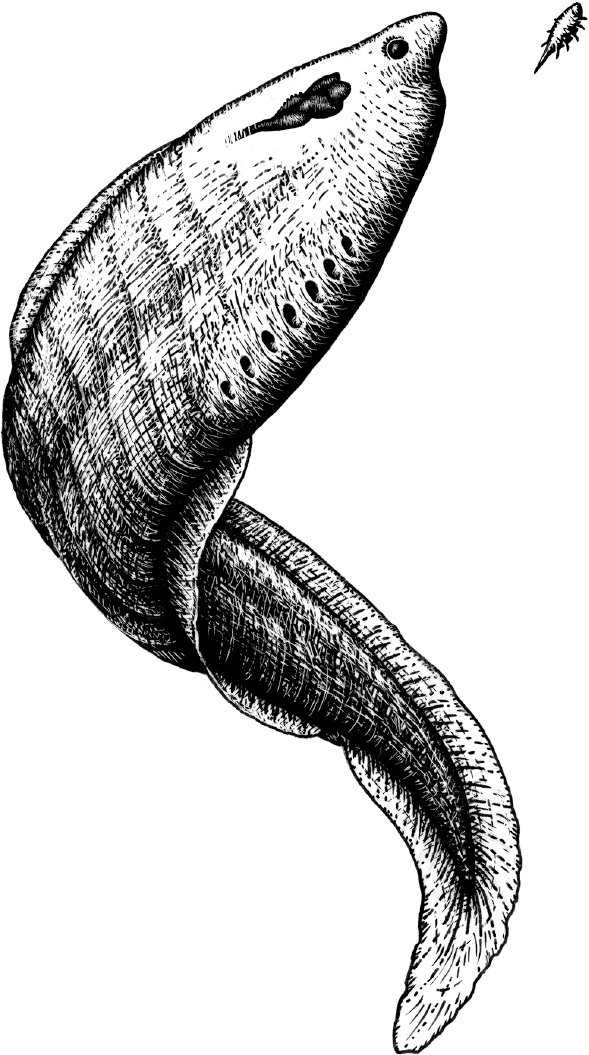

Steering and the First Bilaterians

Your brain 600 million years ago

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

2

The Birth of Good and Bad

Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure.

—JEREMY BENTHAM, AN INTRODUCTION TO THE PRINCIPLES OF MORALS AND LEGISLATION

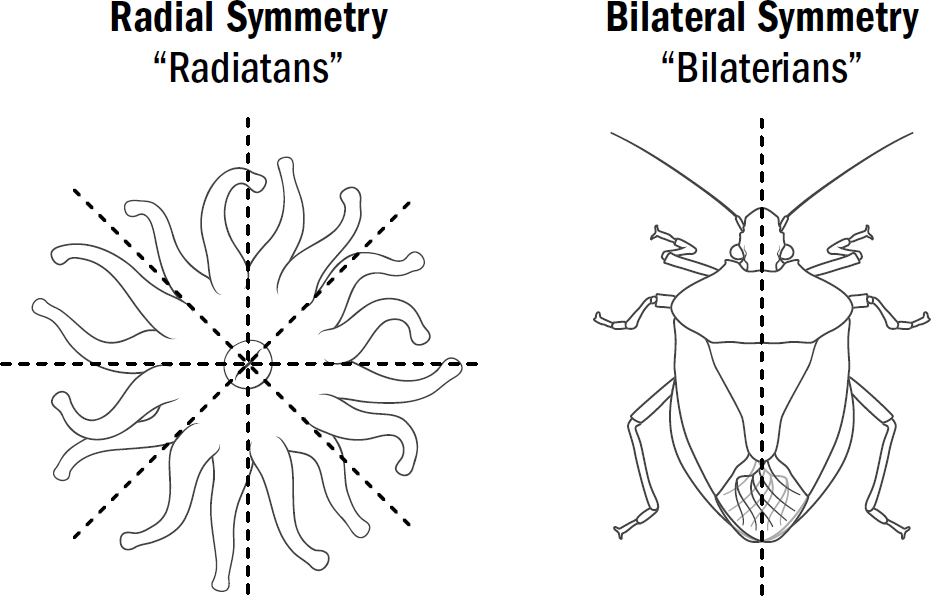

AT FIRST GLANCE, the diversity of the animal kingdom appears remarkable—from ants to alligators, bees to baboons, and crustaceans to cats, animals seem varied in countless ways. But if you pondered this further, you could just as easily conclude that what is remarkable about the animal kingdom is how little diversity there is. Almost all animals on Earth have the same body plan. They all have a front that contains a mouth, a brain, and the main sensory organs (such as eyes and ears), and they all have a back where waste comes out.

Evolutionary biologists call animals with this body plan bilaterians because of their bilateral symmetry. This is in contrast to our most distant animal cousins—coral polyps, anemones, and jellyfish—which have body plans with radial symmetry; that is, with similar parts arranged around a central axis, without any front or back. The most obvious difference between these two categories is how the animals eat. Bilaterians eat by putting food in their mouths and then pooping out waste products from their butts. Radially symmetrical animals have only one opening—a mouth-butt if you will—which swallows food into their stomachs and spits it out. The bilaterians are undeniably the more proper of the two.

Figure 2.1

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

Figure 2.2

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

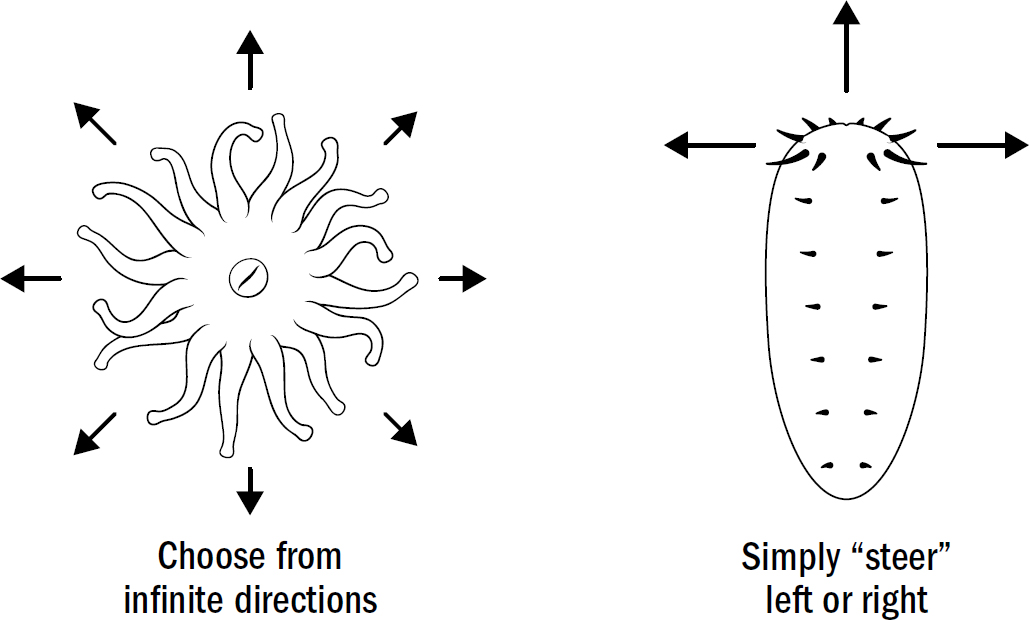

The first animals are believed to have been radially symmetric, and yet today, most animal species are bilaterally symmetric. Despite the diversity of modern bilaterians—from worms to humans—they all descend from a single bilaterian common ancestor who lived around 550 million years ago. Why, within this single lineage of ancient animals, did body plans change from radial symmetry to bilateral symmetry?

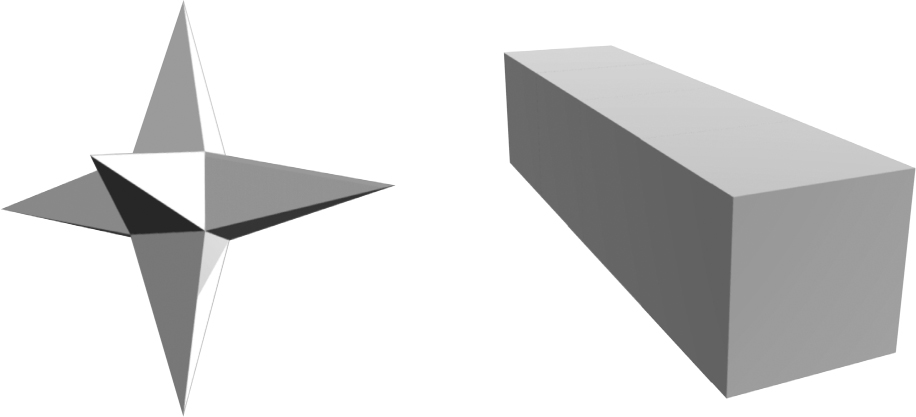

Radially symmetrical body plans work fine with the coral strategy of waiting for food. But they work horribly for the hunting strategy of navigating toward food. Radially symmetrical body plans, if they were to move, would require an animal to have sensory mechanisms to detect the location of food in any direction and then have the machinery to move in any direction. In other words, they would need to be able to simultaneously detect and move in all different directions. Bilaterally symmetrical bodies make movement much simpler. Instead of needing a motor system to move in any direction, they simply need one motor system to move forward and one to turn. Bilaterally symmetrical bodies don’t need to choose the exact direction; they simply need to choose whether to adjust to the right or the left.

Even modern human engineers have yet to find a better structure for navigation. Cars, planes, boats, submarines, and almost every human-built navigation machine is bilaterally symmetric. It is simply the most efficient design for a movement system. Bilateral symmetry allows a movement apparatus to be optimized for a single direction (forward) while solving the problem of navigation by adding a mechanism for turning.

Figure 2.3: Why bilateral symmetry is better for navigation

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

There is another observation about bilaterians, perhaps the more important one: They are the only animals that have brains. This is not a coincidence. The first brain and the bilaterian body share the same initial evolutionary purpose: They enable animals to navigate by steering. Steering was breakthrough #1.

Navigating by Steering

Although we don’t know exactly what the first bilaterians looked like, fossils suggest they were legless wormlike creatures about the size of

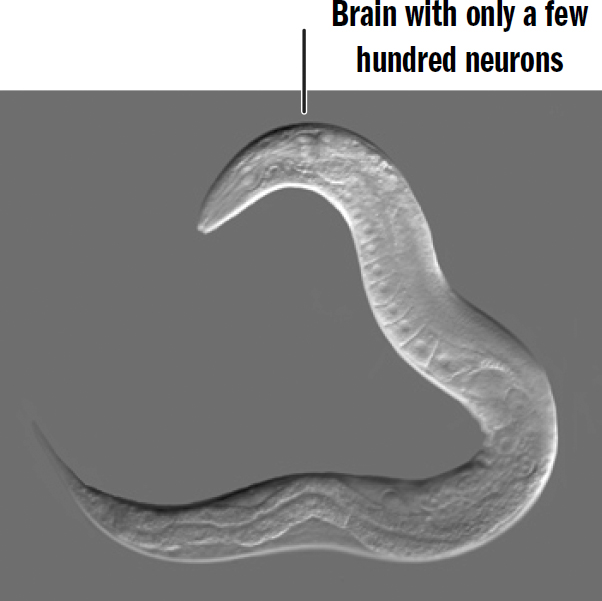

Modern nematodes are believed to have remained relatively unchanged since early bilaterians; these creatures give us a window into the inner workings of our wormlike ancestors. Nematodes are almost literally just the basic template of a bilaterian: not much more than a head, mouth, stomach, butt, some muscles, and a brain.

Figure 2.4: The Ediacaran world

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

Figure 2.5: The nematode C. elegans

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

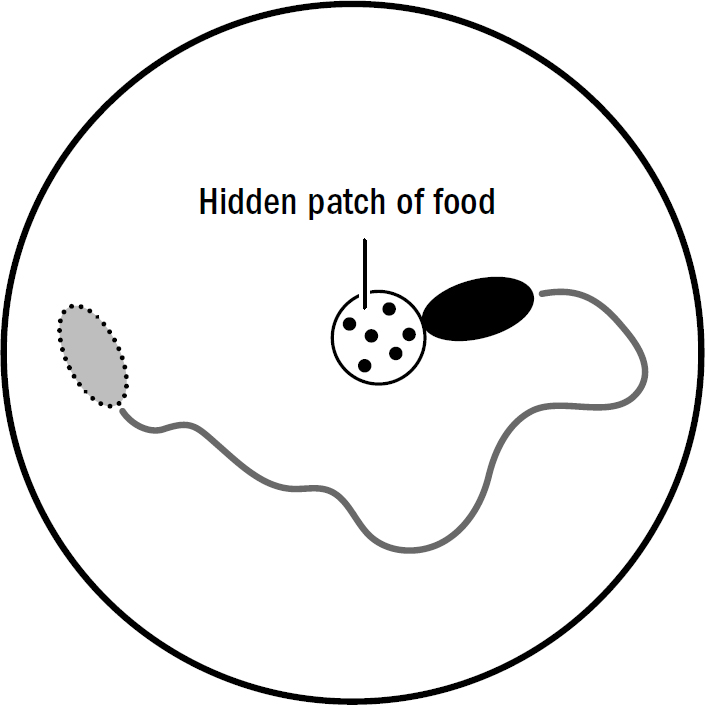

The worm is not using vision; nematodes can’t see. They have no eyes to render any image useful for navigation. Instead, the worm is using smell. The closer it gets to the source of a smell, the higher the concentration of that smell. Worms exploit this fact to find food. All a worm must do is turn toward the direction where the concentration of food particles is increasing, and away from the direction it is decreasing. It is quite elegant how simple yet effective this navigational strategy is. It can be summarized in two rules:

Figure 2.6: Nematode steering toward food

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

- If food smells increase, keep going forward.

- If food smells decrease, turn.

This was the breakthrough of steering. It turns out that to successfully navigate in the complicated world of the ocean floor, you don’t actually need an understanding of that two-dimensional world. You don’t need an understanding of where you are, where food is, what paths you might have to take, how long it might take, or really anything meaningful about the world. All you need is a brain that steers a bilateral body toward increasing food smells and away from decreasing food smells.

This trick of navigating by steering was not new. Single-celled organisms like bacteria navigate around their environments in a similar way. When a protein receptor on the surface of a bacterium detects a stimulus like light, it can trigger a chemical process within the cell that changes the movement of the cell’s protein propellers, thereby causing it to change its direction. This is how single-celled organisms like bacteria swim toward food sources or away from dangerous chemicals. But this mechanism works only on the scale of individual cells, where simple protein propellers can successfully reorient the entire life-form. Steering in an organism that contains millions of cells required a whole new setup, one in which a stimulus activates circuits of neurons and the neurons activate muscle cells, causing specific turning movements. And so the breakthrough that came with the first brain was not steering per se, but steering on the scale of multicellular organisms.

Figure 2.7: Examples of steering decisions made by simple bilaterians like nematodes and flatworms.

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

The First Robot

In the 1980s and 1990s a schism emerged in the artificial intelligence community. On one side were those in the symbolic AI camp, who were focused on decomposing human intelligence into its constituent parts in an attempt to imbue AI systems with our most cherished skills: reasoning, language, problem solving, and logic. In opposition were those in the behavioral AI camp, led by the roboticist Rodney Brooks at MIT, who believed the symbolic approach was doomed to fail because “we will never understand how to decompose human level intelligence until we’ve had a lot of practice with simpler level intelligences.”

Brooks’s argument was partly based on evolution: it took billions of years before life could simply sense and respond to its environment; it took another five hundred million years of tinkering for brains to get good at motor skills and navigation; and only after all of this hard work did language and logic appear. To Brooks, compared to how long it took for sensing and moving to evolve, logic and language appeared in a blink of an eye. Thus he concluded that “language . . . and reason, are all pretty simple once the essence of being and reacting are available. That essence is the ability to move around in a dynamic environment, sensing the surroundings to a degree sufficient to achieve the necessary maintenance of life and reproduction. This part of intelligence is where evolution has concentrated its time—it is much harder.”

By trying to skip simple planes and directly build a 747, they risked completely misunderstanding the principles of how planes work (pitched seats, paned windows, and plastics are the wrong things to focus on). Brooks believed the exercise of trying to reverse-engineer the human brain suffered from this same problem. A better approach was to “incrementally build up the capabilities of intelligence systems, having complete systems at each step.” In other words, to start as evolution did, with simple brains, and add complexity from there.

Many do not agree with Brooks’s approach, but whether you agree with him or not, it was Rodney Brooks who, by any reasonable account, was the first to build a commercially successful domestic robot; it was Brooks who made the first small step toward Rosey. And this first step in the evolution of commercial robots has parallels to the first step in the evolution of brains. Brooks, too, started with steering.

Photograph by Larry D. Moore in 2006. Picture published on Wikipedia at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roomba.

The Roomba could clean all the nooks and crannies of your floor by simply moving around randomly, steering away from obstacles when it bumped into them, and steering toward its charging station when it was low on battery. Whenever the Roomba hit a wall, it would perform a random turn and try to move forward again. When it was low on battery, the Roomba searched for a signal from its charging station, and when it detected the signal, it simply turned in the direction where the signal was strongest, eventually making it back to its charging station.

The navigational strategies of the Roomba and first bilaterians were not identical. But it may not be a coincidence that the first successful domestic robot contained an intelligence not so unlike the intelligence of the first brains. Both used tricks that enabled them to navigate a complex world without actually understanding or modeling that world.

While others remained stuck in the lab working on million-dollar robots with eyes and touch and brains that attempted to compute complicated things like maps and movements, Brooks built the simplest possible robot, one that contained hardly any sensors and that computed barely anything at all. But the market, like evolution, rewards three things above all: things that are cheap, things that work, and things that are simple enough to be discovered in the first place.

While steering might not inspire the same awe as other intellectual feats, it was surely energetically cheap, it worked, and it was simple enough for evolutionary tinkering to stumble upon it. And so it was here where brains began.

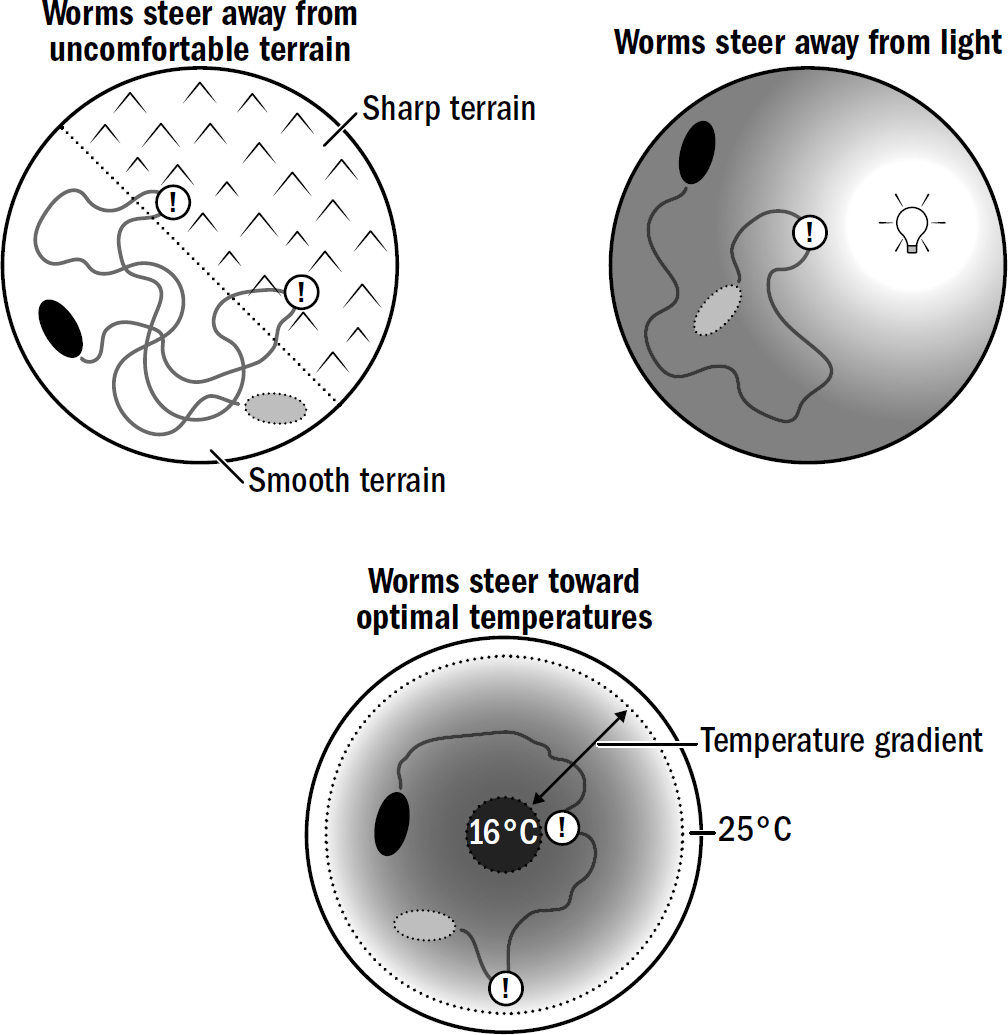

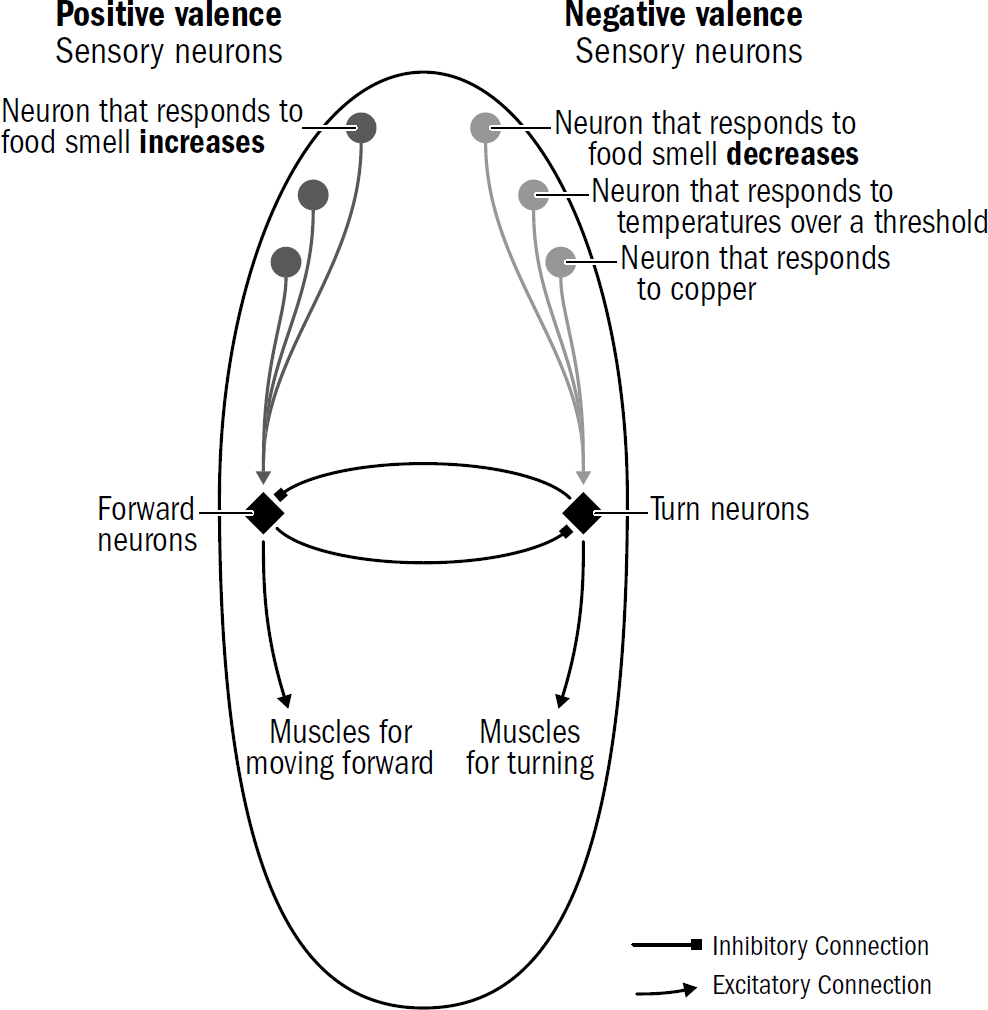

Valence and the Inside of a Nematode’s Brain

Around the head of a nematode are sensory neurons, some of which respond to light, others to touch, and others to specific chemicals. For steering to work, early bilaterians needed to take each smell, touch, or other stimulus they detected and make a choice: Do I approach this thing, avoid this thing, or ignore this thing?

The breakthrough of steering required bilaterians to categorize the world into things to approach (“good things”) and things to avoid (“bad things”). Even a Roomba does this—obstacles are bad; charging station when low on battery is good. Earlier radially symmetric animals did not navigate, so they never had to categorize things in the world like this.

When animals categorize stimuli into good and bad, psychologists and neuroscientists say they are imbuing stimuli with valence. Valence is the goodness or badness of a stimulus. Valence isn’t about a moral judgment; it’s something far more primitive: whether an animal will respond to a stimulus by approaching it or avoiding it. The valence of a stimulus is, of course, not objective; a chemical, image, or temperature, on its own, has no goodness or badness. Instead, the valence of a stimulus is subjective, defined only by the brain’s evaluation of its goodness or badness.

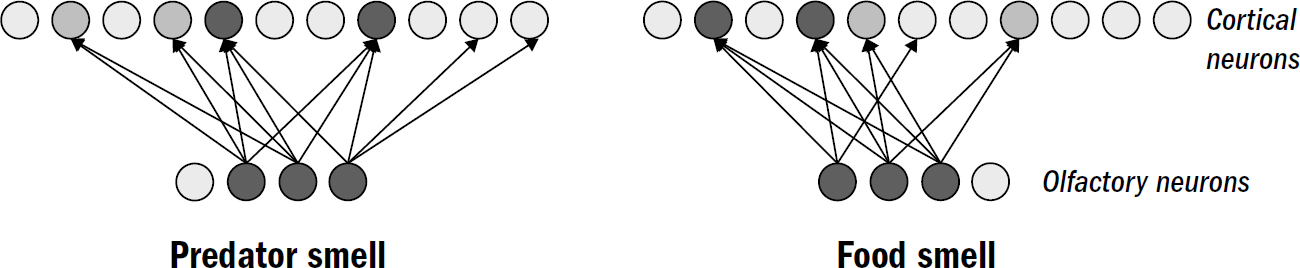

How does a nematode decide the valence of something it perceives? It doesn’t first observe something, ponder it, then decide its valence. Instead, the sensory neurons around its head directly signal the stimulus’s valence. One group of sensory neurons are, effectively, positive-valence neurons; they are directly activated by things nematodes deem good (such as food smells). Another group of sensory neurons are, effectively, negative-valence neurons; they are directly activated by things nematodes deem bad (such as high temperatures, predator smells, bright light).

In nematodes, sensory neurons don’t signal objective features of the surrounding world—they encode steering votes for how much a nematode wants to steer toward or away from something. In more complex bilaterians, such as humans, not all sensory machinery is like this—the neurons in your eyes detect features of images; the valence of the image is computed elsewhere. But it seems that the first brains began with sensory neurons that didn’t care to measure objective features of the world and instead cast the entirety of perception through the simple binary lens of valence.

Consider how a nematode uses this circuit to find food. Nematodes have positive-valence neurons that trigger forward movement when the concentration of a food smell increases. As we saw in the sensory neurons in the nerve net of earlier animals, these neurons quickly adapt to baseline levels of smells. This enables these valence neurons to signal changes across a wide range of smell concentrations. These neurons will generate a similar number of spikes whether a smell concentration goes from two to four parts or from one hundred to two hundred parts. This enables valence neurons to keep nudging the nematode in the right direction. It is the signal for Yes, keep going! from the first whiff of a faraway food smell all the way to the food source.

Figure 2.9: A simplified schematic of the wiring of the first brain

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

This use of adaptation is an example of evolutionary innovations enabling future innovations. Steering toward food in early bilaterians was possible only because adaptation had already evolved in earlier radially symmetric animals. Without adaptation, valence neurons would be either too sensitive (and continuously misfire when smells are too close) or not sensitive enough (unable to detect faraway smells).

At this point, new navigational behaviors could emerge simply by modifying the conditions under which different valence neurons get excited. For example, consider how nematodes navigate toward optimal temperatures. Temperature navigation requires some additional cleverness relative to the simple steering toward smells: the decreasing concentration of a food smell is always bad, but the decreasing temperature of an environment is bad only if a nematode is already too cold. If a nematode is hot, then decreasing temperature is good. A warm bath is miserable in a scorching summer but heavenly in a cold winter. How did the first brains manage to treat temperature fluctuations differently depending on the context?

The Problem of Trade-Offs

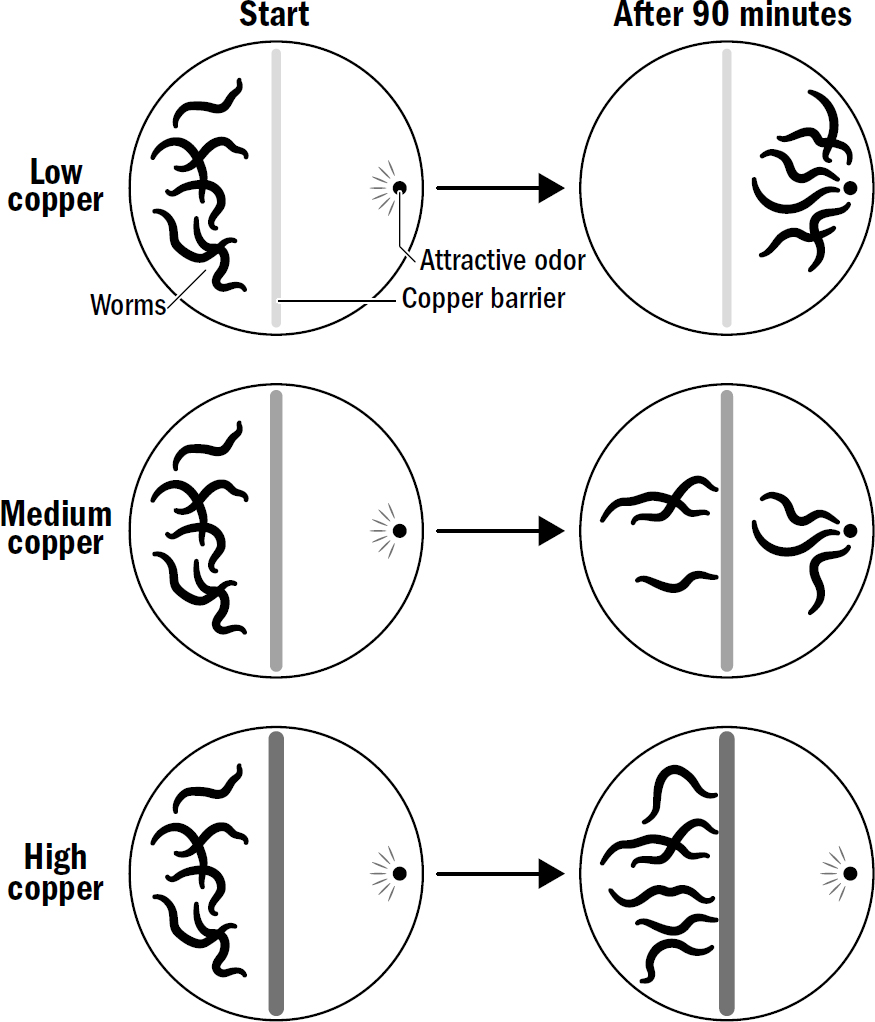

Steering in the presence of multiple stimuli presented a problem: What happens if different sensory cells vote for steering in opposite directions? What if a nematode smells both something yummy and something dangerous at the same time?

At low levels of copper, most nematodes cross the barrier; at intermediate levels of copper, only some do; at high levels of copper, no nematodes are willing to cross the barrier.

Figure 2.10

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

This requirement of integrating input across sensory modalities was likely one reason why steering required a brain and could not have been implemented in a distributed web of reflexes like those in a coral polyp. All these sensory inputs voting for steering in different directions had to be integrated together in a single place to make a single decision; you can go in only one direction at a time. The first brain was this mega-integration center—one big neural circuit in which steering directions were selected.

This is another example of how past innovations enabled future innovations. Just as a bilaterian cannot both go forward and turn at the same time, a coral polyp cannot both open and close its mouth at the same time. Inhibitory neurons evolved in earlier coral-like animals to enable these mutually exclusive reflexes to compete with each other so that only one reflex could be selected at a time; this same mechanism was repurposed in early bilaterians to enable them to make trade-offs in steering decisions. Instead of deciding whether to open or close one’s mouth, bilaterians used inhibitory neurons to decide whether to go forward or turn.

Are You Hungry?

The brain’s ability to rapidly flip the valence of a stimulus depending on internal states is ubiquitous. Compare the salivary ecstasy of the first bite of your favorite dinner after a long day of skipped meals to the bloated nausea of the last bite after eating yourself into a food coma. Within mere minutes, your favorite meal can transform from God’s gift to mankind to something you want nowhere near you.

Internal states are present in a Roomba as well. A Roomba will ignore the signal from its home base when it is fully charged. In this case, the signal from the home base can be said to have neutral valence. When the Roomba’s internal state changes to one where it is low on battery, the signal from home base shifts to having positive valence: the Roomba will no longer ignore the signal from its charging station and will steer toward it to replenish its battery.

Steering requires at least four things: a bilateral body plan for turning, valence neurons for detecting and categorizing stimuli into good and bad, a brain for integrating input into a single steering decision, and the ability to modulate valence based on internal states. But still, evolution continued tinkering. There is another trick that emerged in early bilaterian brains, a trick that further bolstered the effectiveness of steering. That trick was the early kernel of what we now call emotion.

3

The Origin of Emotion

THE BLOOD-BOILING FURY you feel when you hear a friend defend the opposite political party’s most recent gaffe, while hard to define emotionally—perhaps some complex mixture of anger, disappointment, betrayal, and shock—is clearly a bad mood. The tingly serenity you feel when you lie on a warm sunny beach, also hard to define exactly, is still clearly a good mood. Valence exists not only in our assessment of external stimuli but also in our internal states.

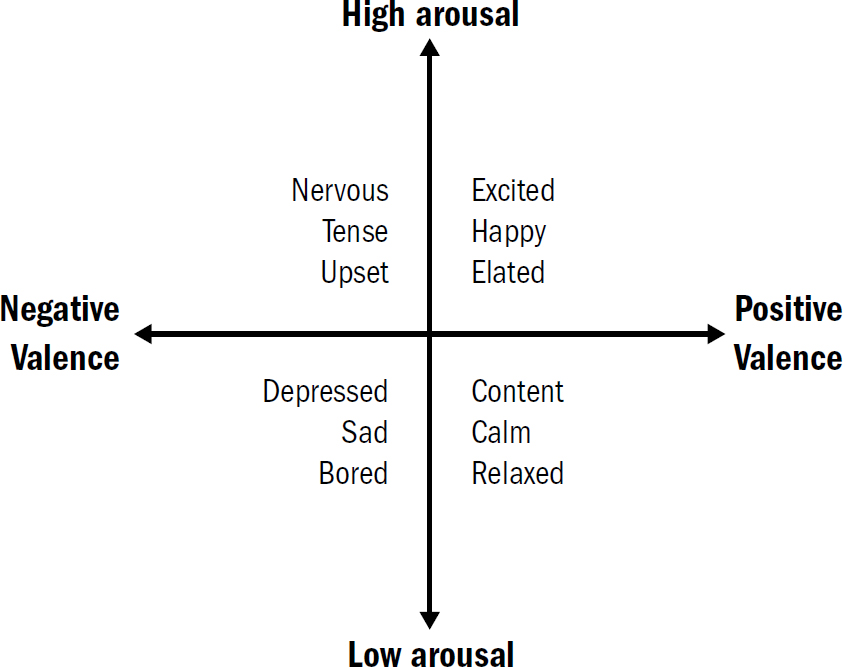

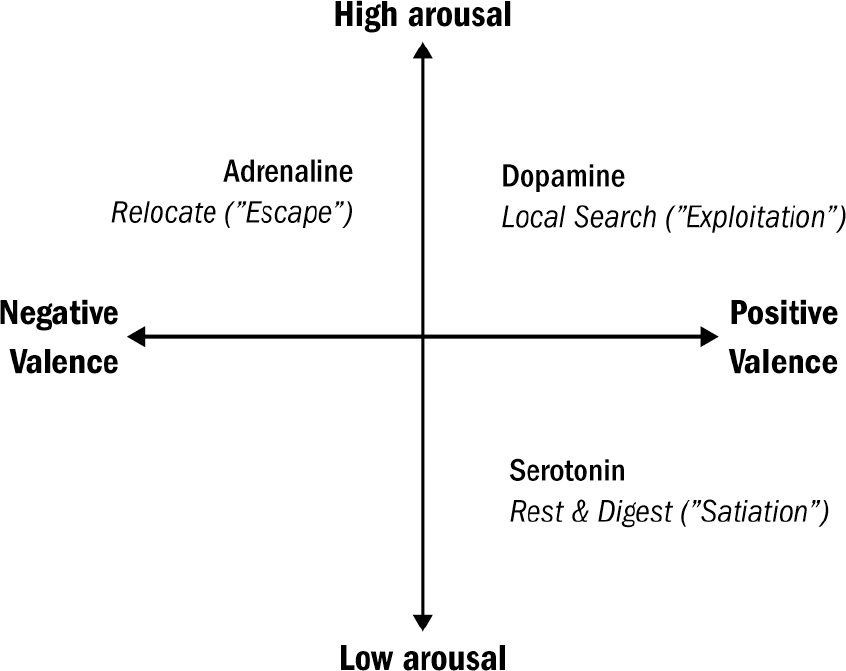

Our internal states are not only imbued with a level of valence, but also a degree of arousal. Blood-boiling fury is not only a bad mood but an aroused bad mood. Different from an unaroused bad mood, like depression or boredom. Similarly, the tingly serenity of lying on a warm beach is not only a good mood but a good mood with low arousal. Different from the highly arousing good mood produced by getting accepted to college or riding a roller coaster (if you like that sort of thing).

Emotions are complicated. Defining and categorizing specific emotions is a perilous business, ripe with cultural bias. In German, there is a word, sehnsucht, that roughly translates to the emotion of wanting a different life; there is no direct English translation. In Persian, the word ænduh expresses the concepts of regret and grief simultaneously; in Dargwa, the word dard expresses the concepts of anxiety and grief simultaneously. In English we have

Figure 3.1: The affective states of humans

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

The universality of affect stretches beyond the bounds of humanity; it is found across the animal kingdom. Affect is the ancient seed from which modern emotions sprouted. But why did affect evolve?

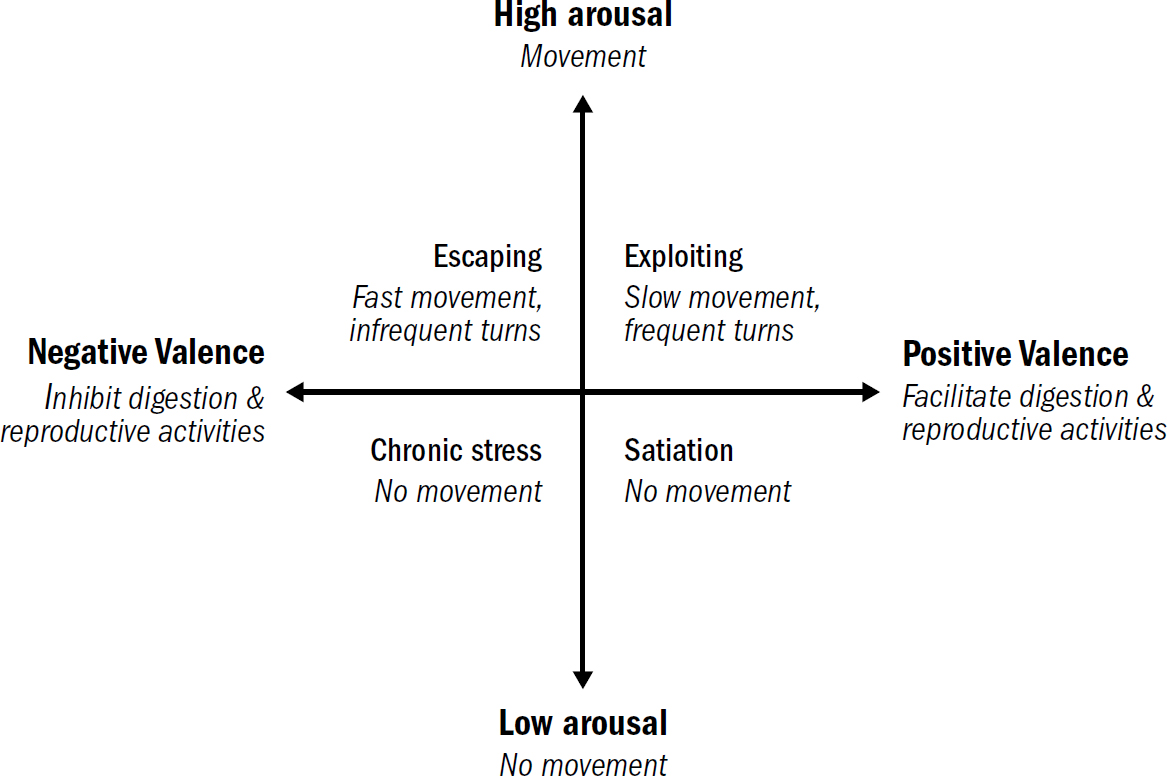

Steering in the Dark

Even nematodes with their minuscule nervous systems have affective states, albeit incredibly simple ones. Nematodes express different levels of arousal: When well fed, stressed, or ill, they hardly move at all and become unresponsive to external stimuli (low arousal); when hungry, detecting food, or sniffing predators, they will continually swim around (high arousal). The affective states of nematodes also express different levels of valence. Positive-valenced stimuli facilitate feeding, digestion, and reproductive activities (a primitive good mood), while negative-valenced stimuli inhibit all of these (a primitive bad mood).

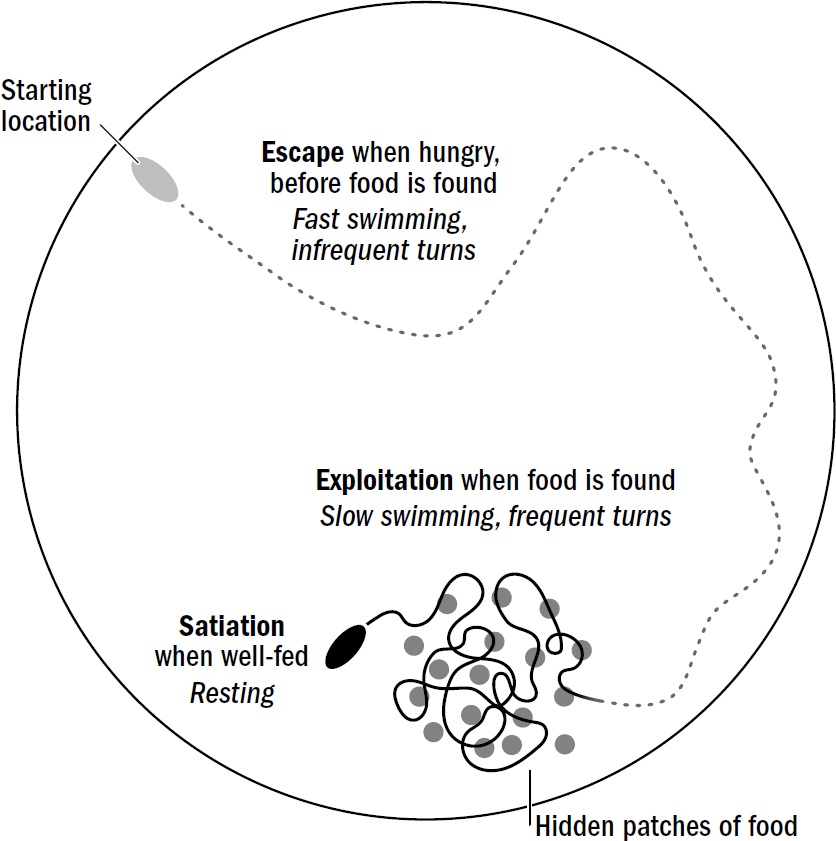

Put these different levels of arousal and valence together and you get a primitive template of affect. Negative-valenced stimuli trigger a behavioral repertoire of fast swimming and infrequent turns, which can be thought of as the most primitive version of an aroused bad mood (which is often called the state of escaping), while the detection of food triggers a repertoire of slow swimming and frequent turns, which can be thought of as the most primitive version of an aroused good mood (which is often called the state of exploiting). Escaping leads worms to rapidly change location; exploiting leads worms to search their local surroundings (to exploit their surroundings for food). Although nematodes don’t share the same complexity of emotions as humans—they do not know the rush of young love or the bittersweet tears of sending a child off to college—they clearly show the basic template of affect. These incredibly simple affective states of nematodes offer a clue as to why affect evolved in the first place.

Figure 3.2: The affective states of nematodes

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

Suppose you put an unfed nematode in a big petri dish with a hidden patch of food. Even if you obscure any food smell for the nematode to steer toward, the nematode won’t just dumbly sit waiting for a whiff of food. The nematode will rapidly swim and relocate itself; in other words, it will escape. It does this because one thing that triggers escape is hunger. When the nematode happens to stumble upon the hidden food, it will immediately slow down and start rapidly turning, remaining in the same general location that it found food—it will shift from escaping to exploiting. Eventually, after eating enough food, the worm will stop moving and become immobile and unresponsive. It will shift to satiation.

Scientists tend to shy away from the term affective states in simple bilaterians such as nematodes and instead use the safer term behavioral states; this avoids the suggestion that nematodes are, in fact, feeling anything. Conscious experience is a philosophical quagmire we will only briefly touch on later. Here, at least, this issue can be sidestepped entirely; the conscious experience of affect—whatever it is and however it works—likely evolved after the raw underlying mechanisms of affect. This can be seen even in humans—the parts of the human brain that generate the experience of negative or positive affective states are evolutionarily newer and distinct from the parts of the brain that generate the reflexive avoidance and approach responses.

Figure 3.3

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

Sensory stimuli, especially the simple ones detected by nematodes, offer transient clues, not consistent certainties, of what exists in the real world. In the wild, outside of a scientist’s petri dish, food does not make perfectly distributed smell gradients—water currents can distort or even completely obscure smells, disrupting a worm’s ability to steer toward food or away from predators. These persistent affective states are a trick to overcome this challenge: If I detect a passing sniff of food that quickly fades, it is likely that there is food nearby even if I no longer smell it. Therefore, it is more effective to persistently search my surroundings after encountering food, as opposed to only responding to food smells in the moment that they are detected. Similarly, a worm passing through an area full of predators won’t experience a constant smell of predators but rather catch a transient hint of one nearby; if a worm wants to escape, it is a good idea to persistently swim away even after the smell has faded.

Like a pilot trying to fly a plane while looking through an opaque or obscured window, she would have no choice but to learn to fly in the darkness, using only the clues offered by the flickers of the outside world. Similarly, worms had to evolve a way to “steer in the dark”—to make steering decisions in the absence of sensory stimuli. The first evolutionary solution was affect, behavioral repertoires that can be triggered by external stimuli but persist long after they have faded.

This feature of steering shows up even in a Roomba. Indeed, Roombas were designed to have different behavioral states for the same reason. Normally, they explore rooms by moving around randomly. However, if a Roomba encounters a patch of dirt, it activates Dirt Detect, which changes its repertoire; it begins turning in circles in a local area. This new repertoire is triggered by the detection of dirt but persists for a time even after dirt is no longer detected. Why was the Roomba designed to do this? Because it works—detecting a patch of dirt in one location is predictive of nearby patches of dirt. Thus, a simple rule to improve the speed of getting all the dirt is to shift toward local search for a time after detecting dirt. This is exactly the same reason nematodes evolved to shift their behavioral state from exploration to exploitation after encountering food and locally search their surroundings.

Dopamine and Serotonin

The brain of a nematode generates these affective states using chemicals called neuromodulators. Two of the most famous neuromodulators are dopamine and serotonin. Antidepressants, antipsychotics, stimulants, and psychedelics all exert their effects by manipulating these neuromodulators. Many psychiatric conditions, including depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and schizophrenia are believed to be caused, at least in part, by imbalances in neuromodulators. Neuromodulators evolved long before humans appeared; they began their connection to affect as far back as the first bilaterians.

Unlike excitatory and inhibitory neurons, which have specific, short-lived effects on only the specific neurons they connect to, neuromodulatory neurons have subtle, long-lasting, and wide-ranging effects on many neurons. Different neuromodulatory neurons release different neuromodulators—dopamine neurons release dopamine, serotonin neurons release serotonin. And neurons throughout an animal’s brain have different types of receptors for different types of neuromodulators—neuromodulators can gently inhibit some neurons while simultaneously activating others; they can make some neurons more likely to spike while making others less likely to spike; they can make some neurons more sensitive to activation while dulling the responses of others. They can even accelerate or slow down the process of adaptation. Put all these effects together, and these neuromodulators can tune the neural activity across the entire brain. It is the balance of these different neuromodulators that determines a nematode’s affective state.

The simple brain of the nematode offers a window into the first, or at least very early, functions of dopamine and serotonin. In the nematode, dopamine is released when food is detected around the worm, whereas serotonin is released when food is detected inside the worm. If dopamine is the something-good-is-nearby chemical, then serotonin is the something-good-is-actually-happening chemical. Dopamine drives the hunt for food; serotonin drives the enjoyment of it once it is being eaten.

Figure 3.4: Role of neuromodulators in affective states of first bilaterians

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

And crucially, all these neuromodulatory neurons—like valence neurons—are also sensitive to internal states. Dopamine neurons are more likely to respond to food cues when an animal is hungry.

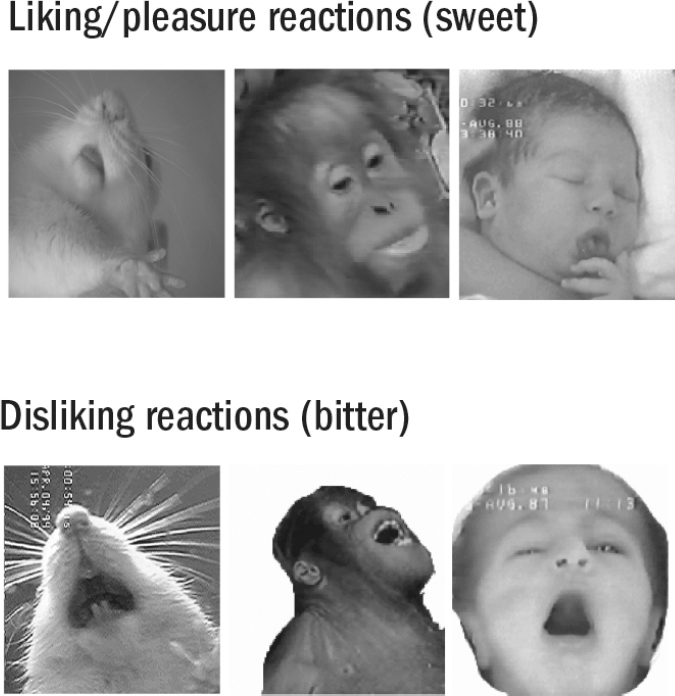

This connection between dopamine and reward has caused dopamine to be—incorrectly—labeled the “pleasure chemical.” Kent Berridge, a neuroscientist at the University of Michigan, came up with a experimental paradigm to explore the relationship between dopamine and pleasure. Rats, like humans, make distinct facial expressions when tasting things they like, such as yummy sugar pellets, and things they don’t like, such as bitter liquid. A baby will smile when tasting warm milk and spit when tasting bitter water; rats will lick their lips when they taste yummy food and gape their mouths and shake their heads when they taste gross food. Berridge realized he could use the frequency of these different facial reactions as a proxy for identifying pleasure in rats.

Images from Kent Berridge (personal correspondence). Used with permission.

To the surprise of many, Berridge found that increasing dopamine levels in the brains of rats had no impact on the degree and frequency of their pleasurable facial expressions to food. While dopamine will cause rats to consume ridiculous amounts of food, the rats do not indicate they are doing so because they like the food more. Rats do not express a higher number of pleasurable lip smacks. If anything, they express more disgust with the food, despite eating more of it. It is as if rats can’t stop eating even though they no longer enjoy it.

Dopamine is not a signal for pleasure itself; it is a signal for the anticipation of future pleasure. Heath’s patients weren’t experiencing pleasure; to the contrary, they often became extremely frustrated at their inability to satisfy the incredible cravings the button produced.

Berridge proved that dopamine is less about liking things and more about wanting things. This discovery makes sense given the evolutionary origin of dopamine. In nematodes, dopamine is released when they are near food but not when they are consuming food. The dopamine-triggered behavioral state of exploitation in nematodes—in which they slow down and search their surroundings for food—is in many ways the most primitive version of wanting. As early as the first bilaterians, dopamine was a signal for the anticipation of a future good thing, not the signal for the good thing itself.

Dopamine and serotonin are primarily involved in navigating the happy side of affective states—the different flavors of positive affect. There are additional neuromodulators, equally ancient, that undergird the mechanisms of negative affect—of stress, anxiety, and depression.

When Worms Get Stressed

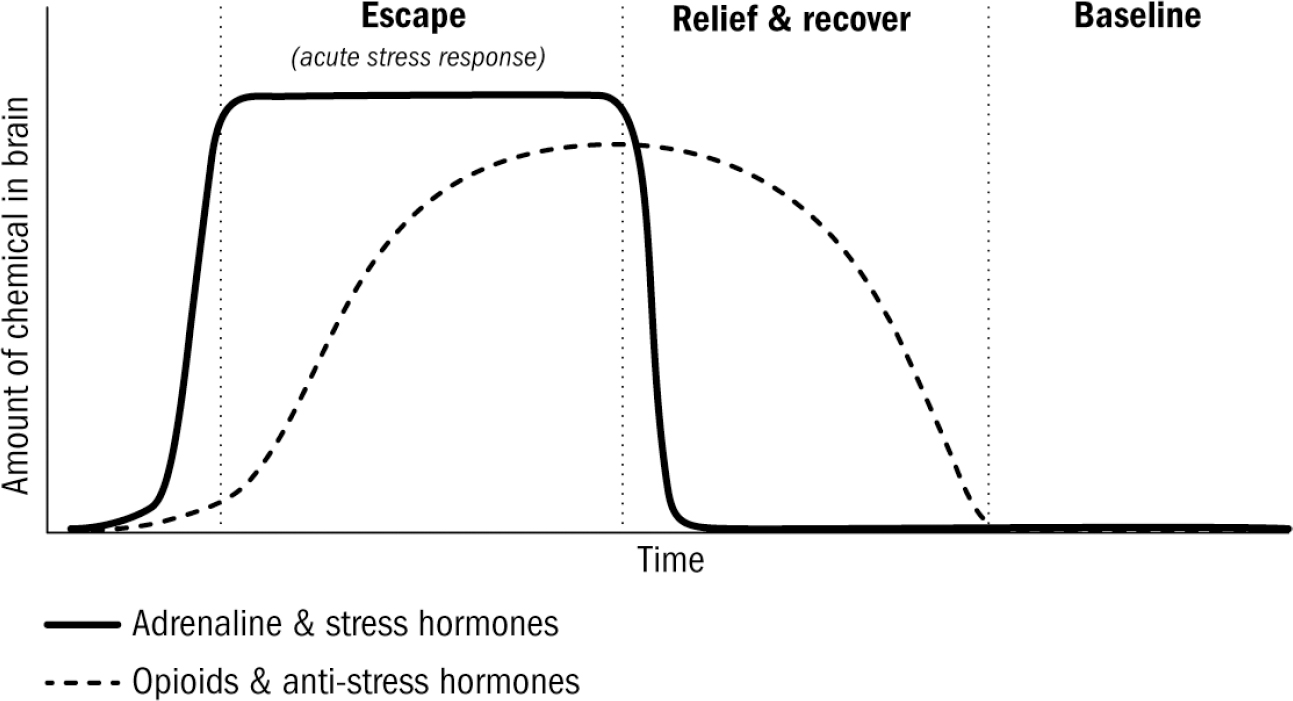

These people aren’t being eaten by lions, or starving, or freezing to death. These people are dying because their brains are killing them. Choosing to commit suicide, knowingly consuming deadly drugs, or binge eating oneself into obesity are, of course, behaviors generated by our brains. Any attempt to understand animal behavior, brains, and intelligence itself is wholly incomplete without understanding this enigma: Why would evolution have created brains with such a catastrophic and seemingly ridiculous flaw? The point of brains, as with all evolutionary adaptations, is to improve survival. Why, then, do brains generate such obviously self-destructive behaviors?

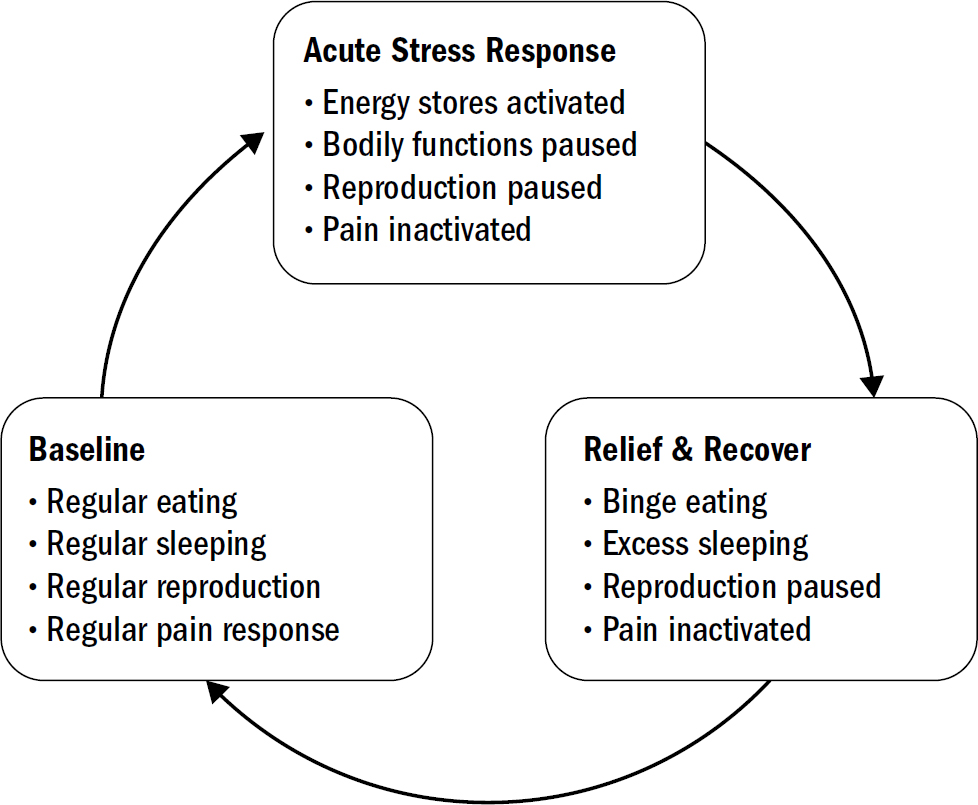

Figure 3.6: The time course of stress and anti-stress hormones

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

These anti-stress hormones like opioids differed from dopamine and serotonin in Kent Berridge’s rat facial expression experiments. While dopamine had no impact on liking reactions, giving opioids to a rat did, in fact, substantially increase their liking reactions to food. This makes sense given what we now know about the evolutionary origin of opioids. Opioids are the relief-and-recover chemical after experiencing stress: stress hormones turn positive-valence responses off (decreasing liking), but when a stressor is gone, the leftover opioids turn these valence responses back on (increasing liking). Opioids make everything better; they increase liking reactions and decrease disliking reactions; increasing pleasure and inhibiting pain.

Figure 3.7: The ancient stress cycle, originating from first bilaterians

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

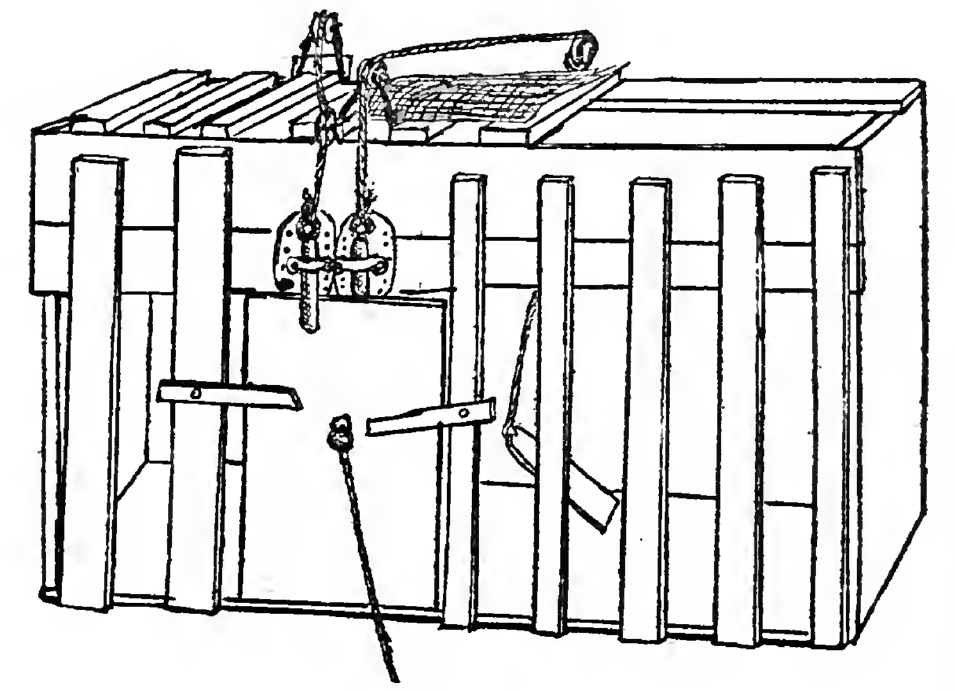

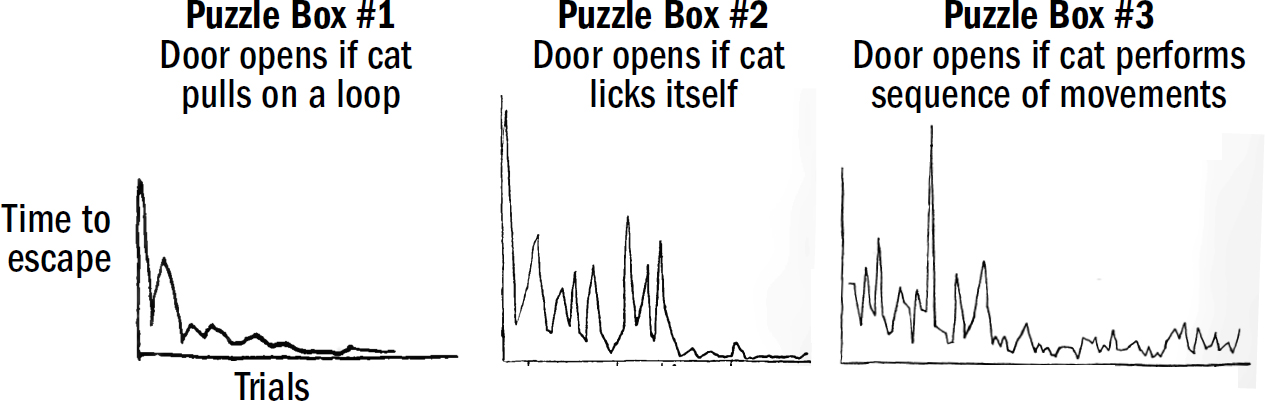

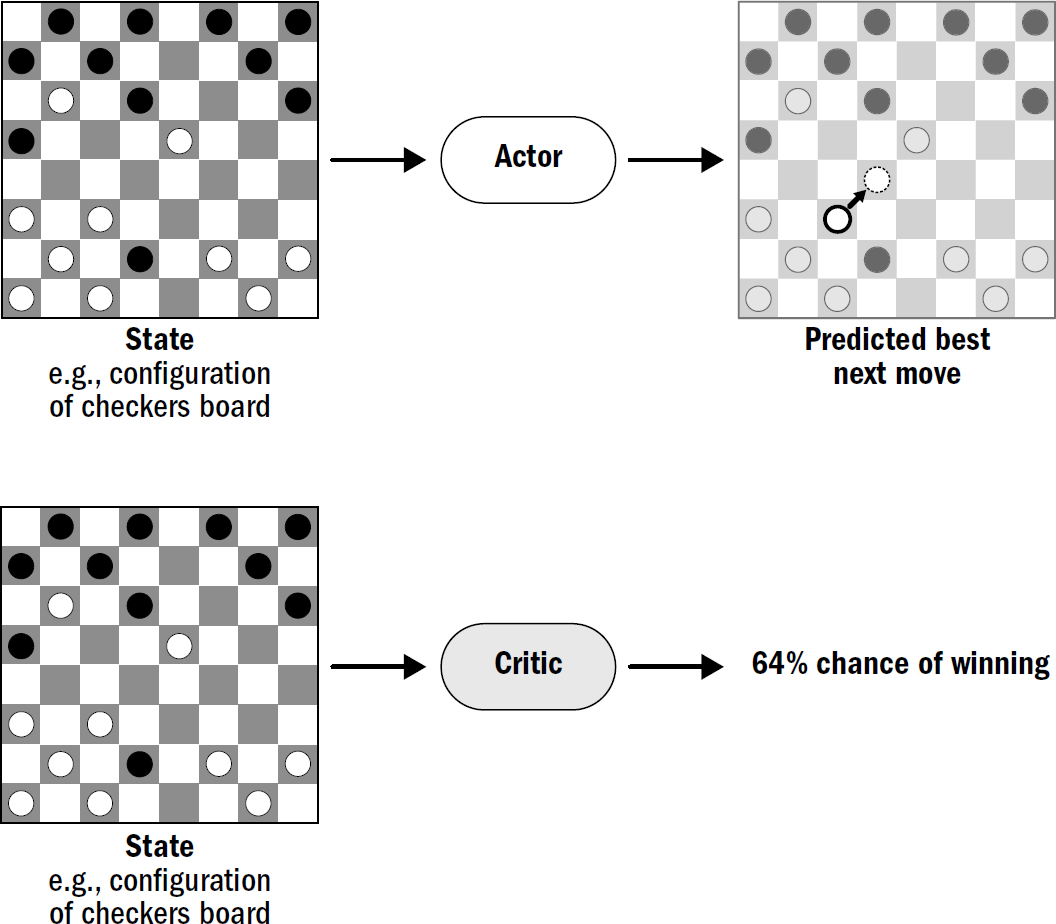

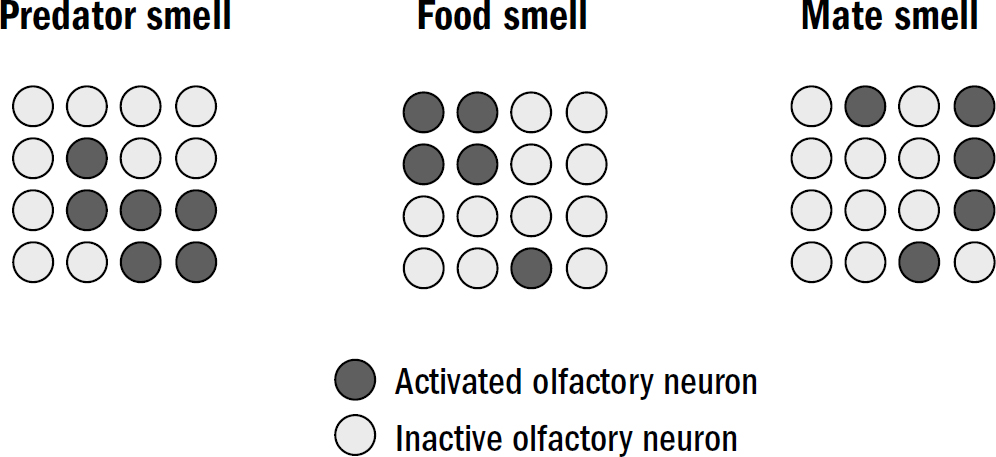

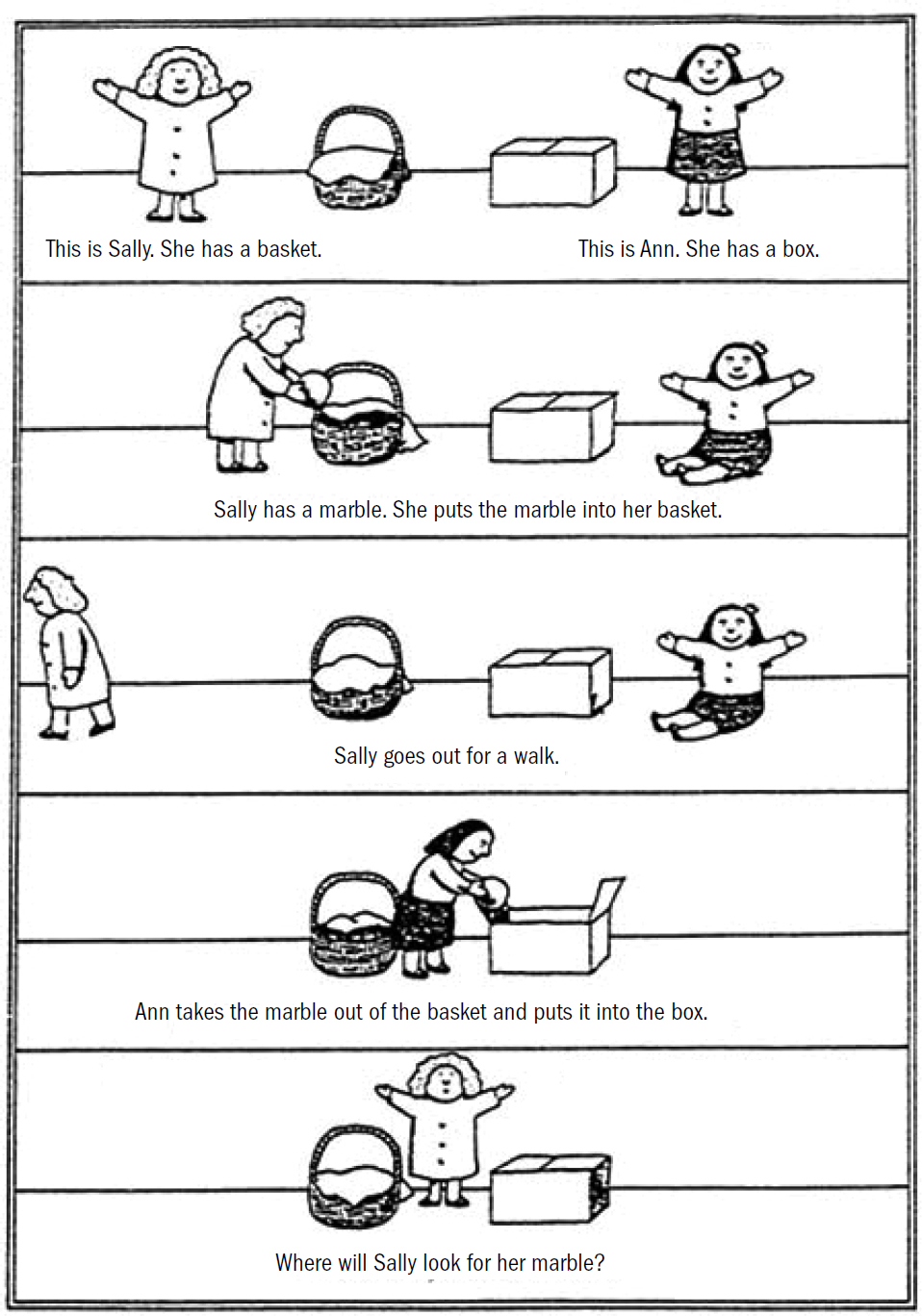

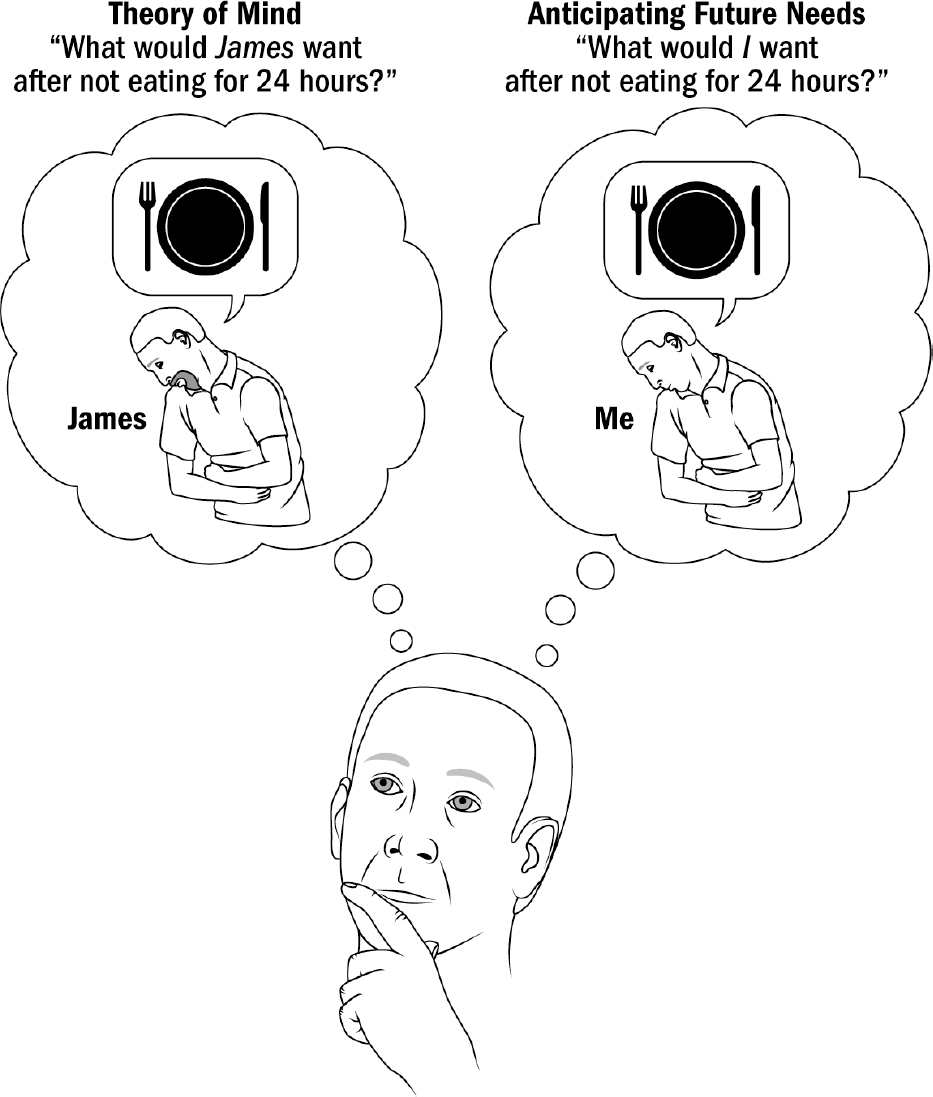

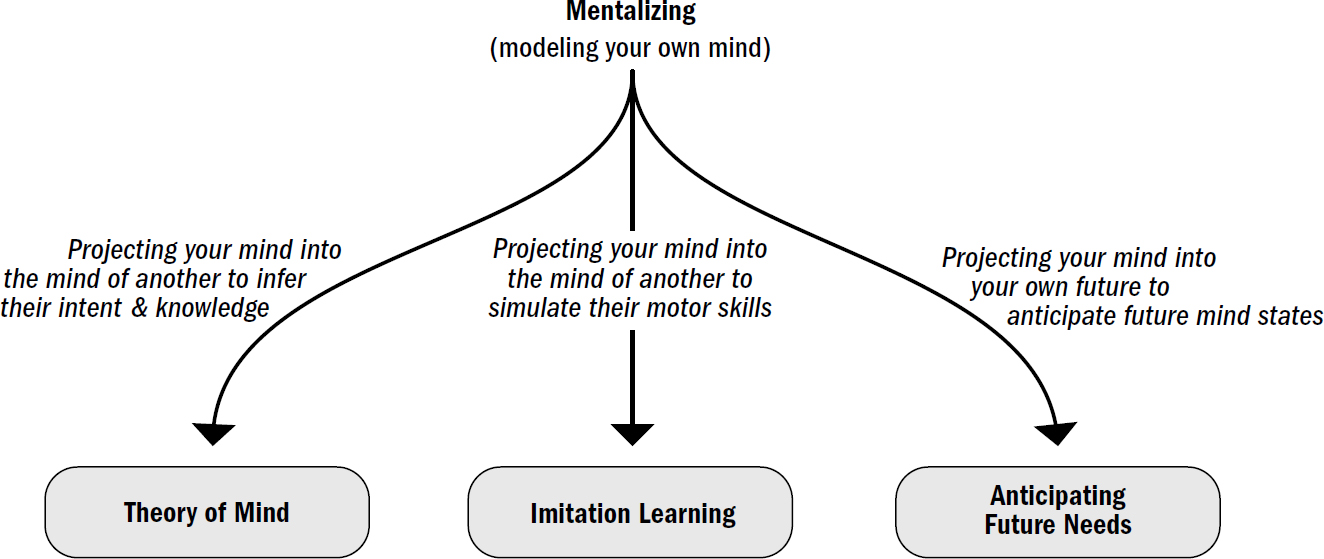

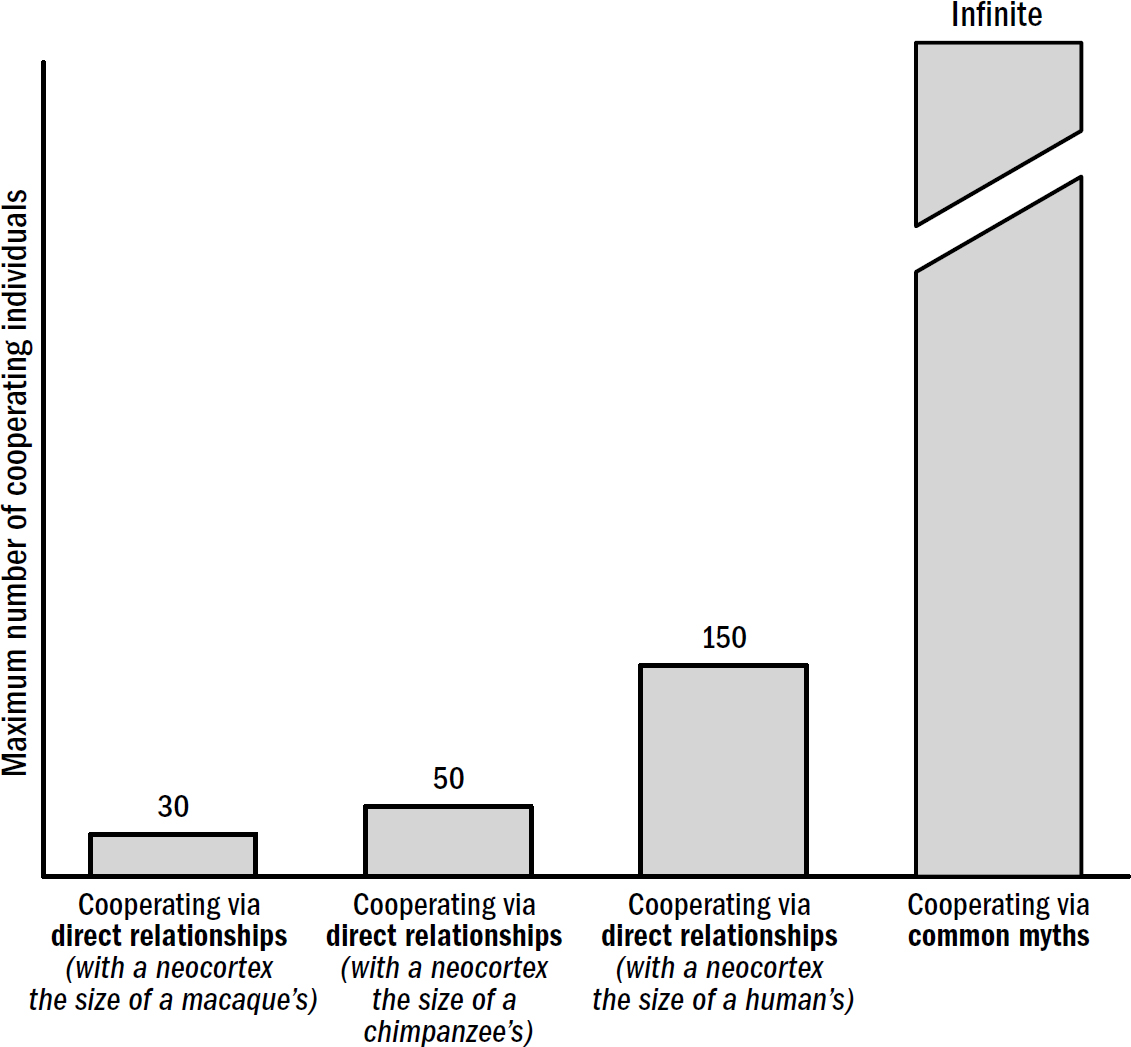

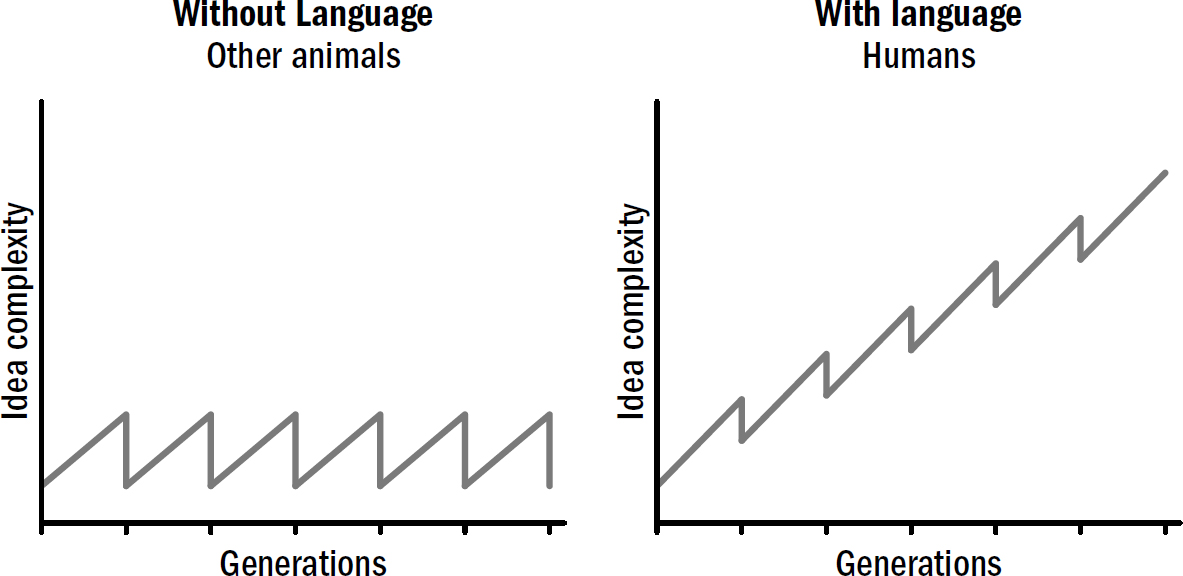

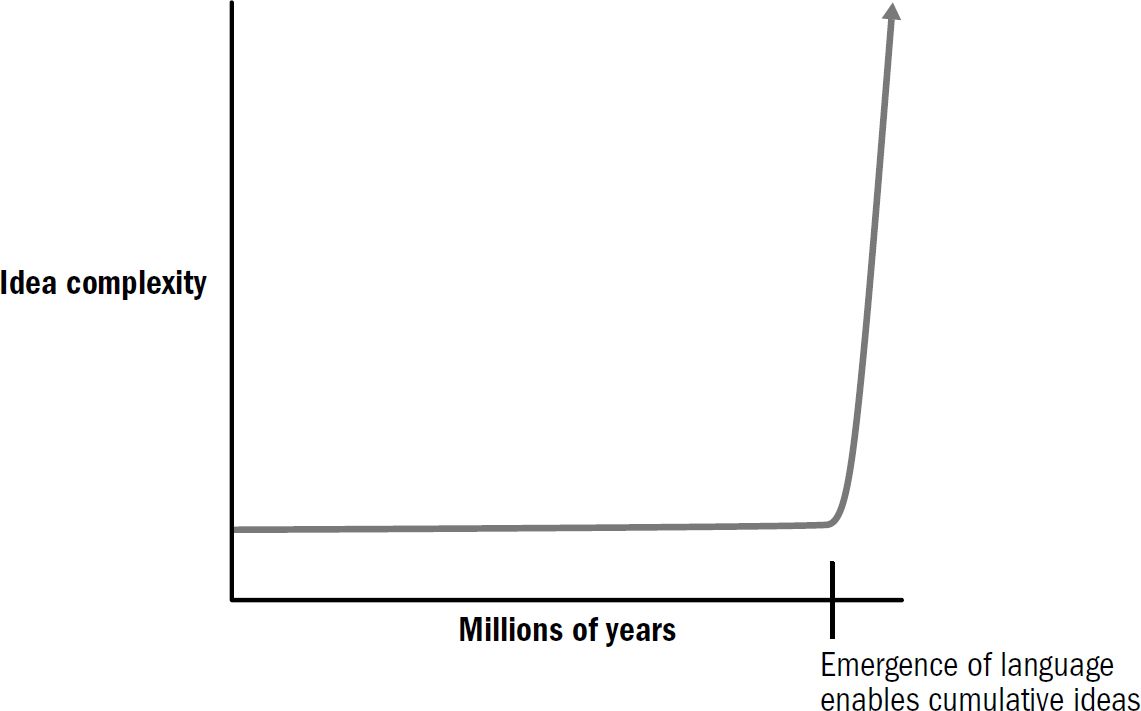

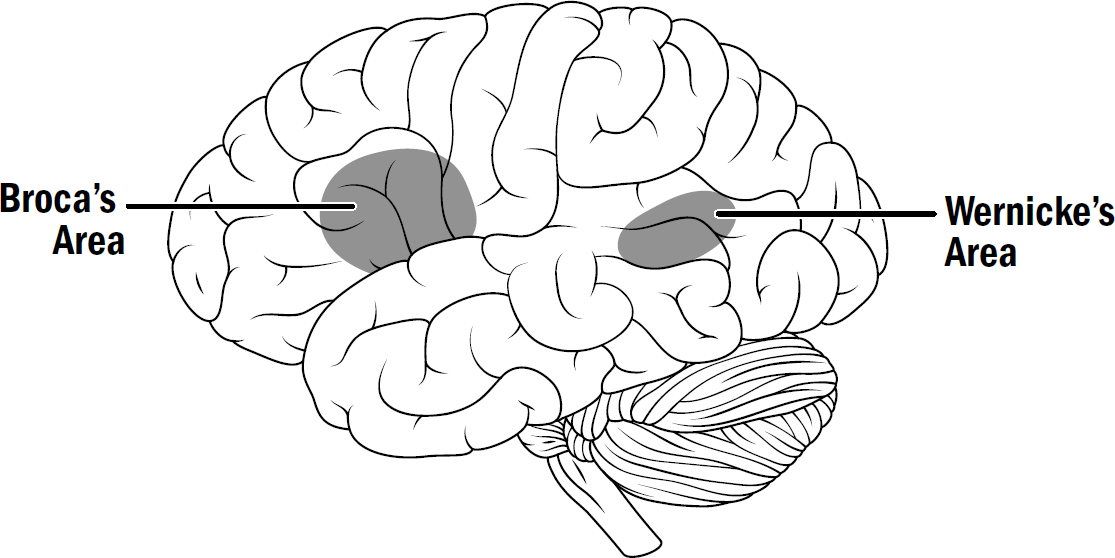

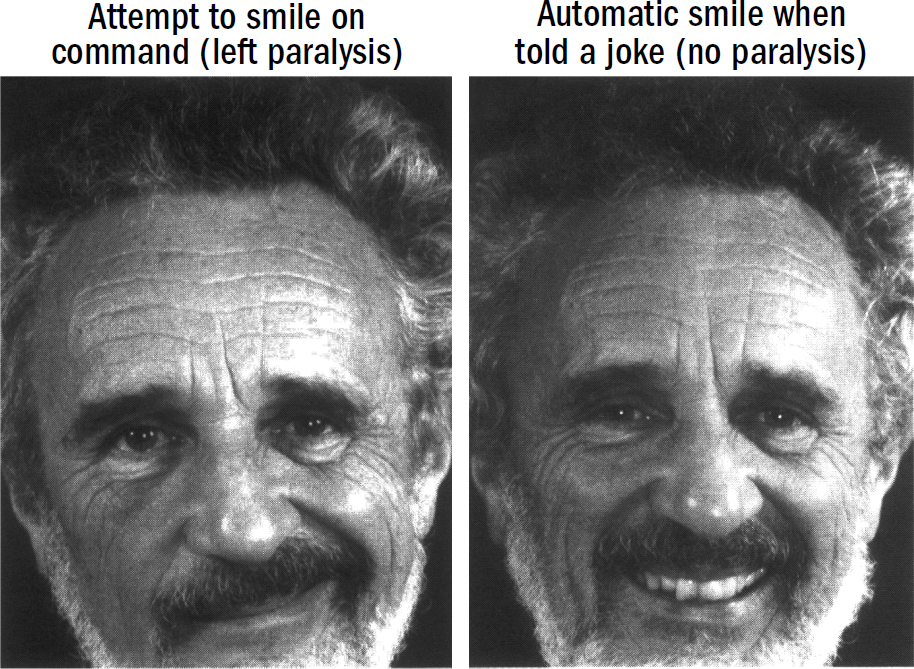

The Blahs and Blues