- 1. Intro to Design Patterns: Welcome to Design Patterns

- It started with a simple SimUDuck app

- But now we need the ducks to FLY

- But something went horribly wrong...

- Joe thinks about inheritance...

- How about an interface?

- What would you do if you were Joe?

- The one constant in software development

- Zeroing in on the problem...

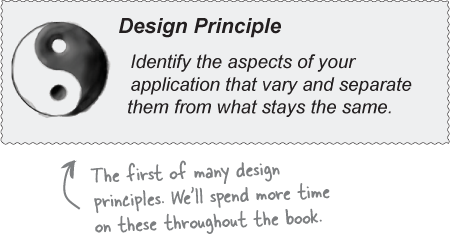

- Separating what changes from what stays the same

- Designing the Duck Behaviors

- Implementing the Duck Behaviors

- Integrating the Duck Behavior

- More integration...

- Testing the Duck code

- Setting behavior dynamically

- The Big Picture on encapsulated behaviors

- HAS-A can be better than IS-A

- Speaking of Design Patterns...

- Design Puzzle

- Overheard at the local diner...

- Overheard in the next cubicle...

- The power of a shared pattern vocabulary

- How do I use Design Patterns?

- Tools for your Design Toolbox

- Design Patterns Crossword

- Design Puzzle Solution

- Design Patterns Crossword Solution

- 2. The Observer Pattern: Keeping your Objects in the Know

- The Weather Monitoring application overview

- Unpacking the WeatherData class

- Our Goal

- Stretch Goal

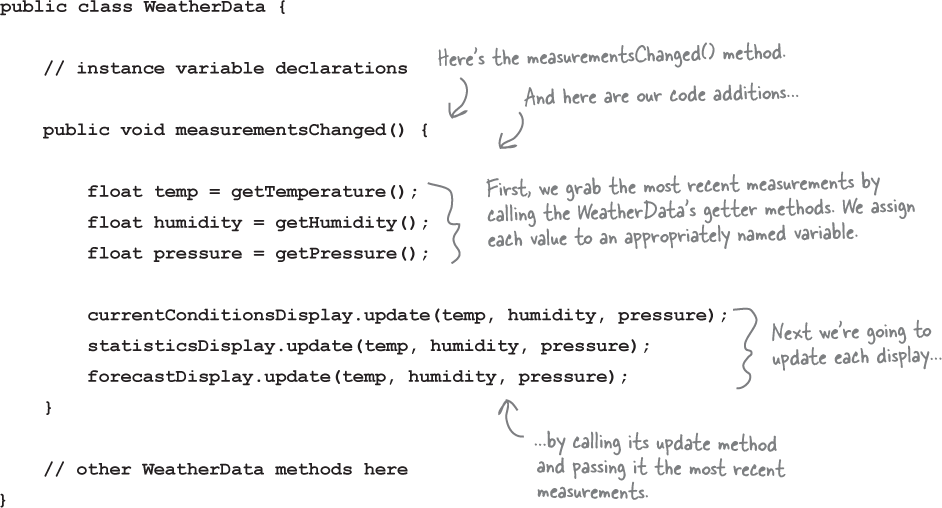

- Taking a first, misguided SWAG at the Weather Station

- What’s wrong with our implementation anyway?

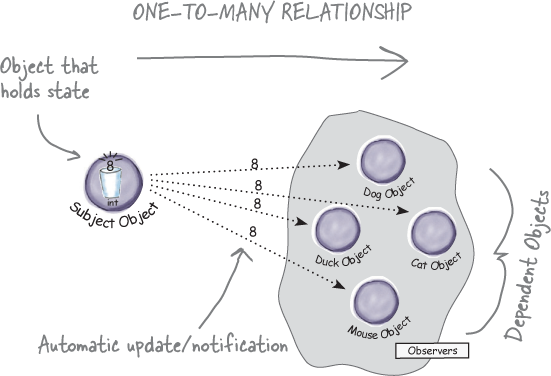

- Meet the Observer Pattern

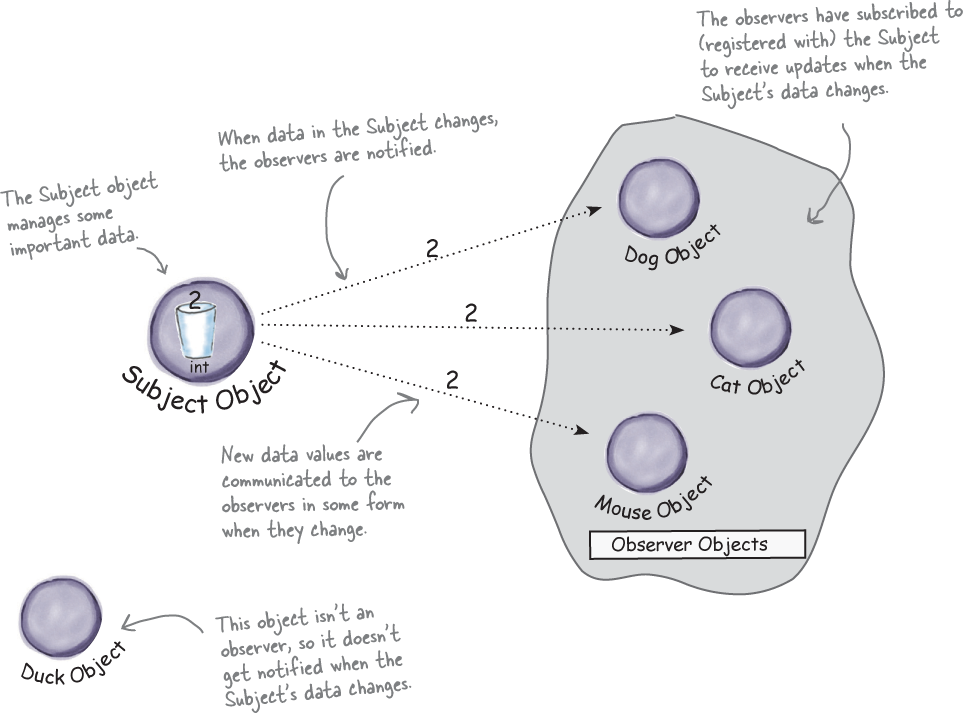

- Publishers + Subscribers = Observer Pattern

- A day in the life of the Observer Pattern

- Five-minute drama: a subject for observation

- Two weeks later...

- The Observer Pattern defined

- The Observer Pattern: the Class Diagram

- The Power of Loose Coupling

- Cubicle conversation

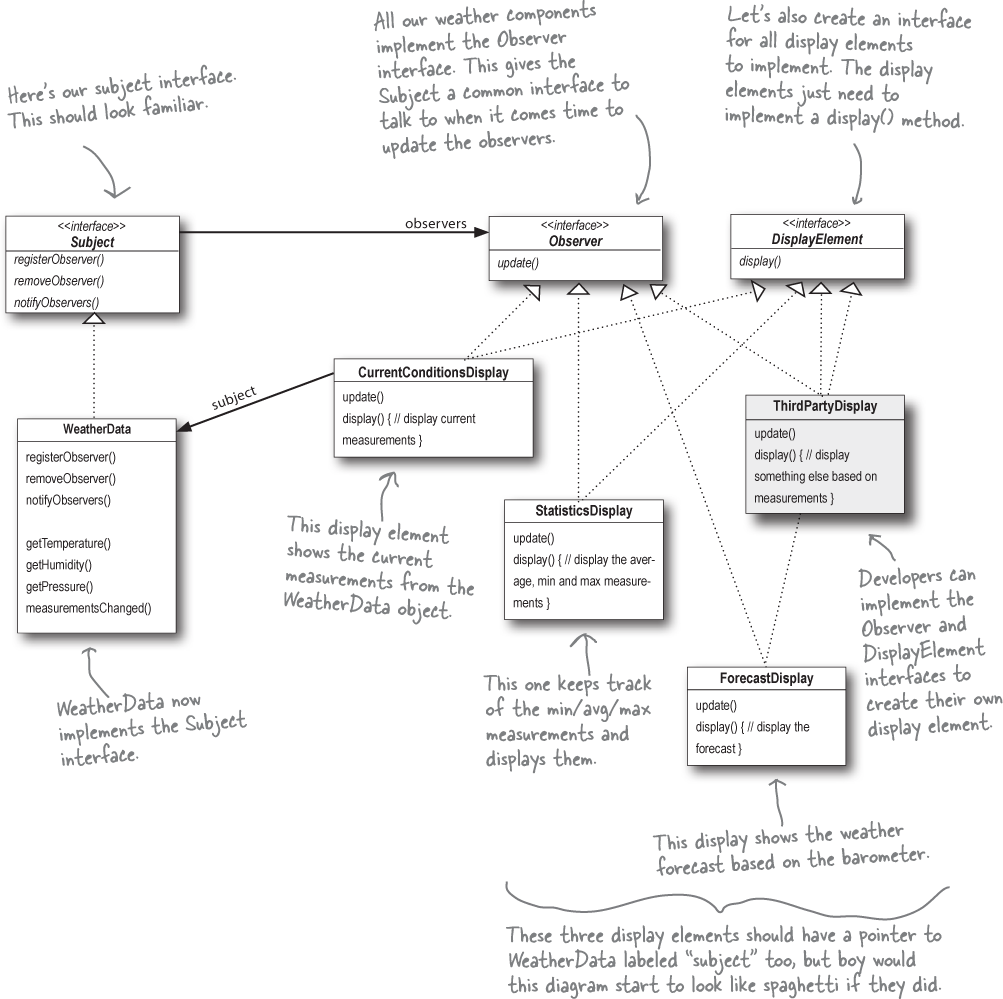

- Designing the Weather Station

- Implementing the Weather Station

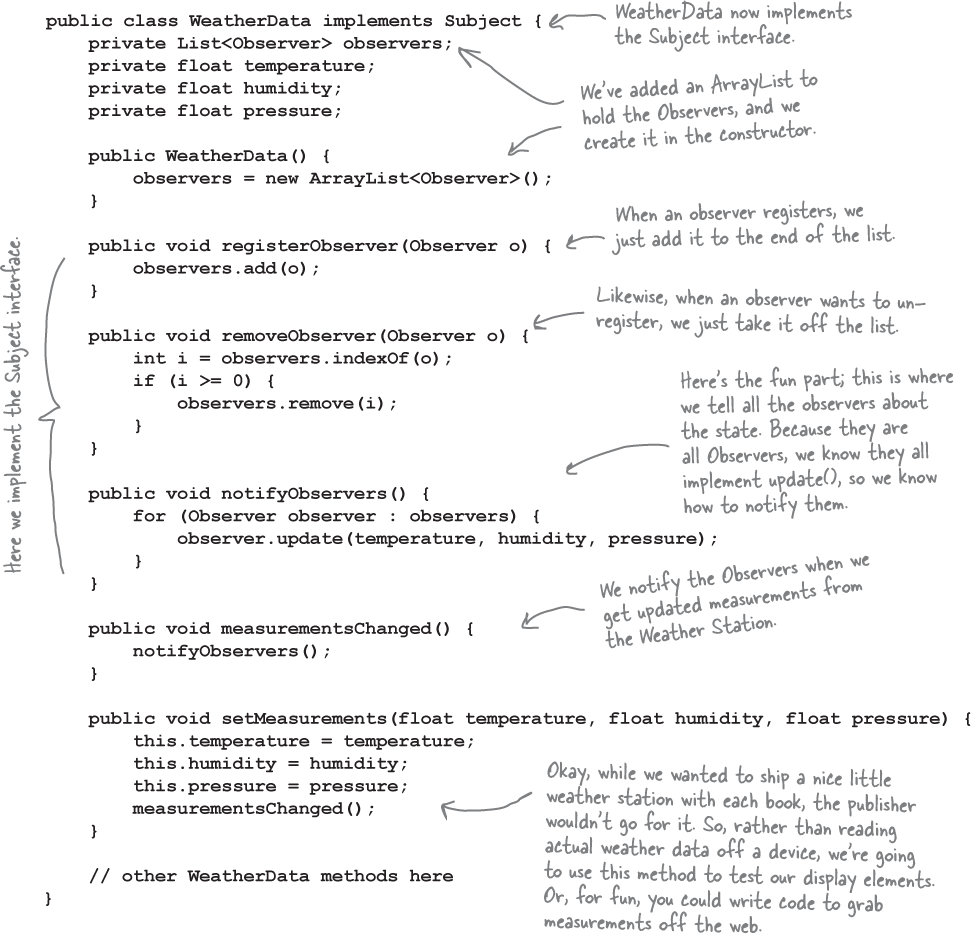

- Implementing the Subject interface in WeatherData

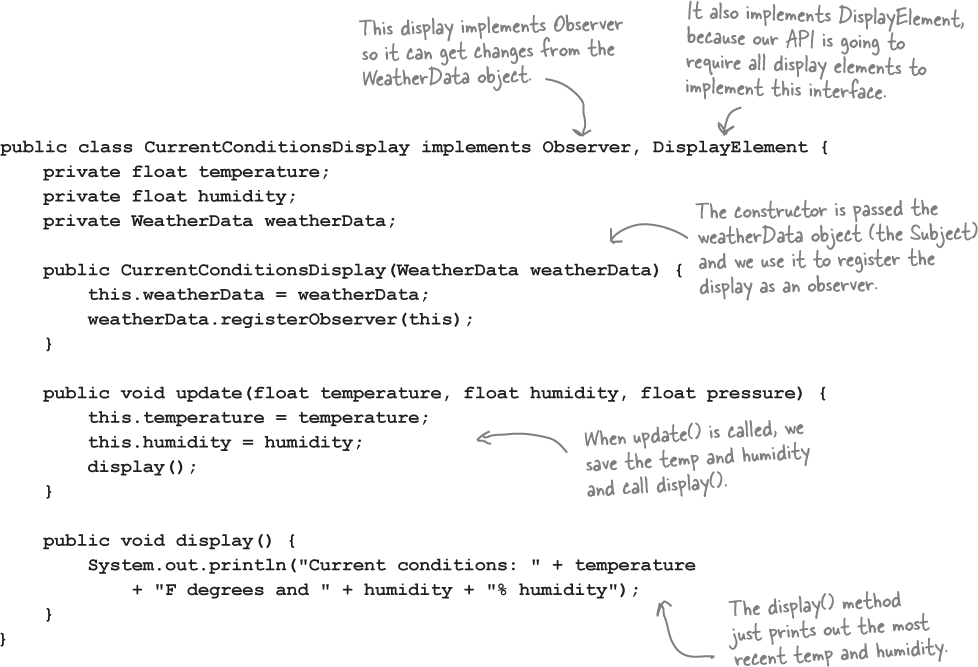

- Now, let’s build those display elements

- Power up the Weather Station

- Looking for the Observer Pattern in the Wild

- Coding the life-changing application

- Meanwhile back at Weather-O-Rama

- Code Magnets

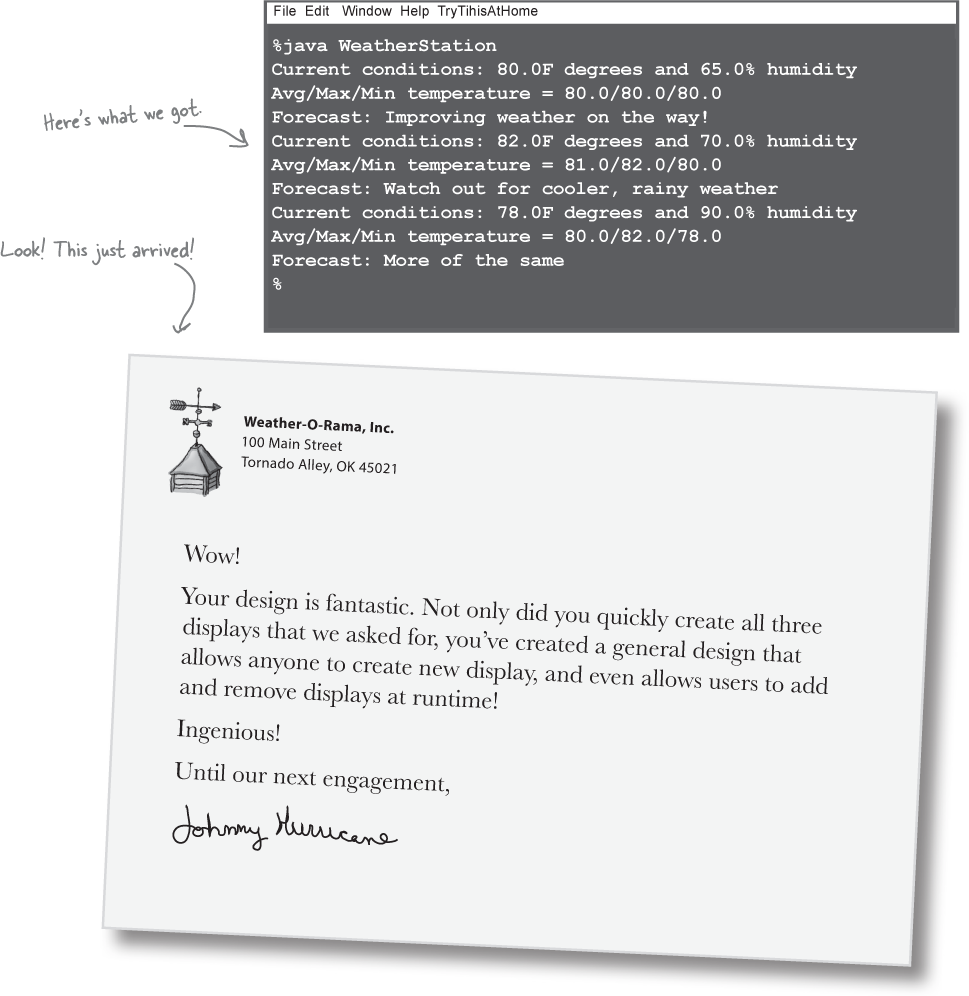

- Test Drive the new code

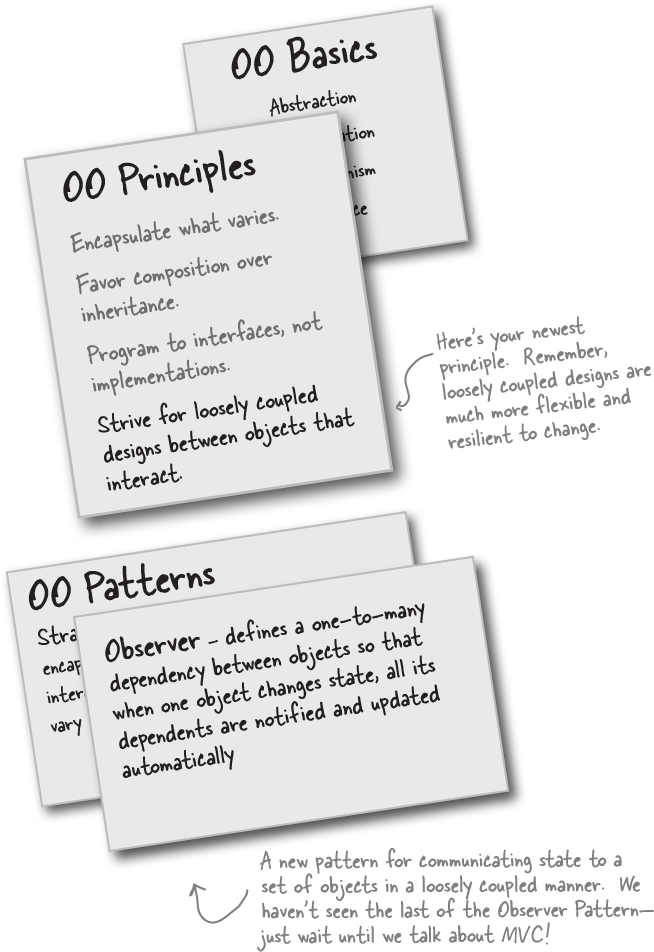

- Tools for your Design Toolbox

- Design Principle Challenge

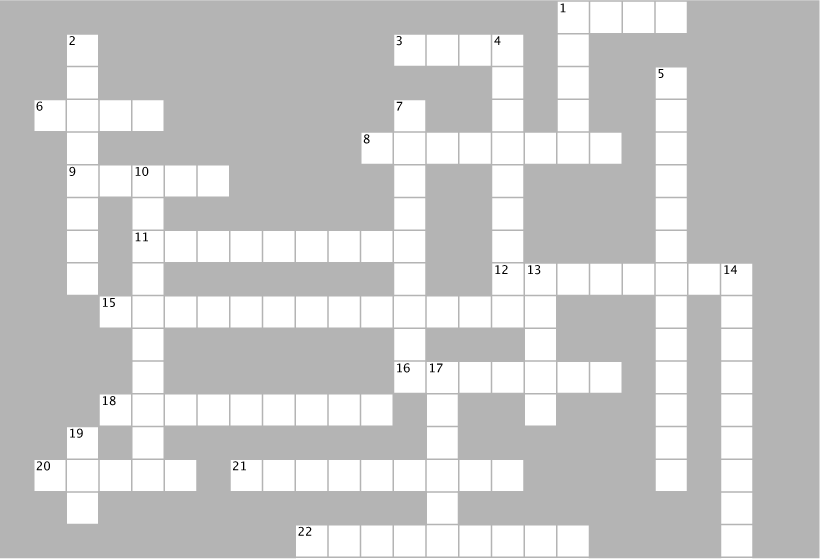

- Design Patterns Crossword

- Code Magnets Solution

- Design Patterns Crossword Solution

Head First Design Patterns

Second Edition

Building Extensible and Maintainable Object-Oriented Software

Eric Freeman and Elisabeth Robson

Head First Design Patterns

by Eric Freeman and Elisabeth Robson

Copyright © 2020 Eric Freeman & Elisabeth Robson. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc. , 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472.

O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles ( http://oreilly.com ). For more information, contact our corporate/institutional sales department: 800-998-9938 or corporate@oreilly.com .

- Editors: Michele Cronin and Melissa Duffield

- Production Editor: Kristen Brown

- Copyeditor: FILL IN COPYEDITOR

- Proofreader: FILL IN PROOFREADER

- Indexer: FILL IN INDEXER

- Interior Designer: David Futato

- Cover Designer: Karen Montgomery

- Illustrator: Rebecca Demarest

- December 2020: Second Edition

Revision History for the Second Edition

- 2020-06-05: First Early Release

See http://oreilly.com/catalog/errata.csp?isbn=9781492078005 for release details.

The O’Reilly logo is a registered trademark of O’Reilly Media, Inc. Head First Design Patterns, the cover image, and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc.

The views expressed in this work are those of the author(s), and do not represent the publisher’s views. While the publisher and the author(s) have used good faith efforts to ensure that the information and instructions contained in this work are accurate, the publisher and the author(s) disclaim all responsibility for errors or omissions, including without limitation responsibility for damages resulting from the use of or reliance on this work. Use of the information and instructions contained in this work is at your own risk. If any code samples or other technology this work contains or describes is subject to open source licenses or the intellectual property rights of others, it is your responsibility to ensure that your use thereof complies with such licenses and/or rights.

978-1-492-07800-5

[FILL IN]

Chapter 1. Intro to Design Patterns: Welcome to Design Patterns

Figure 1-1.

Someone has already solved your problems. In this chapter, you’ll learn why (and how) you can exploit the wisdom and lessons learned by other developers who’ve been down the same design problem road and survived the trip. Before we’re done, we’ll look at the use and benefits of design patterns, look at some key object oriented design principles, and walk through an example of how one pattern works. The best way to use patterns is to load your brain with them and then recognize places in your designs and existing applications where you can apply them. Instead of code reuse, with patterns you get experience reuse.

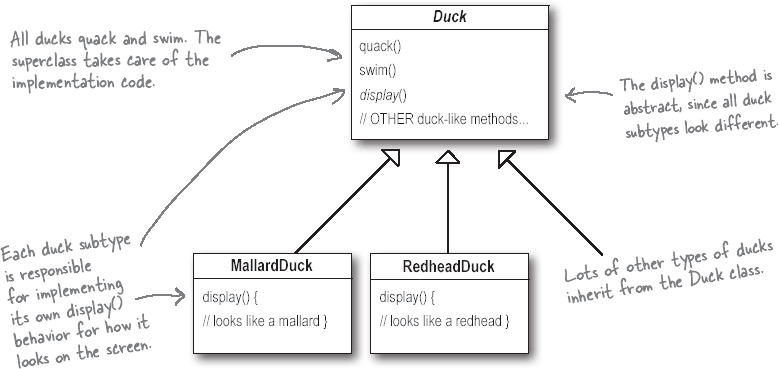

It started with a simple SimUDuck app

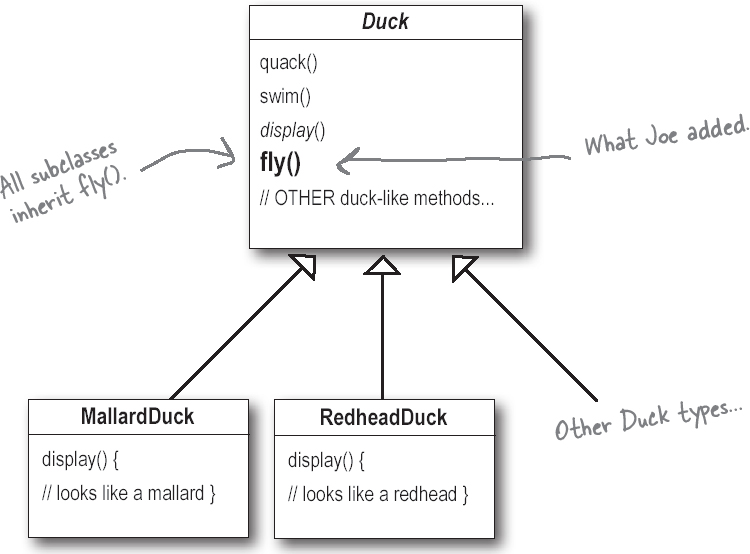

Joe works for a company that makes a highly successful duck pond simulation game, SimUDuck. The game can show a large variety of duck species swimming and making quacking sounds. The initial designers of the system used standard OO techniques and created one Duck superclass from which all other duck types inherit.

Figure 1-2.

Figure 1-3.

In the last year, the company has been under increasing pressure from competitors. After a week long off-site brainstorming session over golf, the company executives think it’s time for a big innovation. They need something really impressive to show at the upcoming shareholders meeting in Maui next week.

But now we need the ducks to FLY

The executives decided that flying ducks is just what the simulator needs to blow away the competitors. And of course Joe’s manager told them it’ll be no problem for Joe to just whip something up in a week. “After all,” said Joe’s boss, “he’s an OO programmer... how hard can it be?”

Figure 1-4.

Figure 1-5.

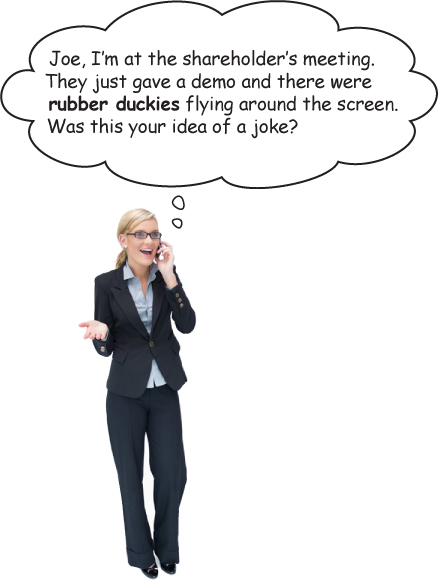

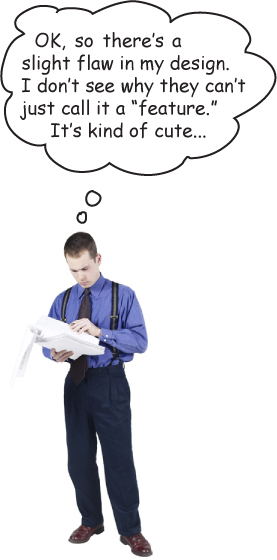

But something went horribly wrong...

Figure 1-6.

Figure 1-7.

What happened?

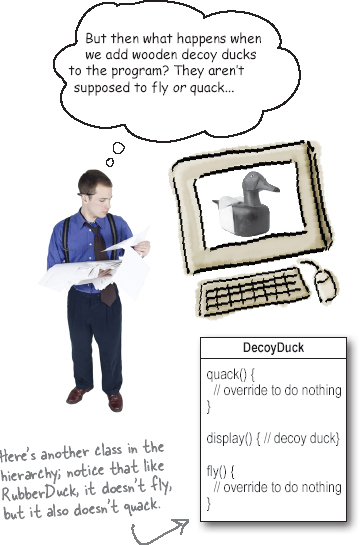

Joe failed to notice that not all subclasses of Duck should fly. When Joe added new behavior to the Duck superclass, he was also adding behavior that was not appropriate for some Duck subclasses. He now has flying inanimate objects in the SimUDuck program.

A localized update to the code caused a non-local side effect (flying rubber ducks)!

Figure 1-8.

Figure 1-9.

Note

What Joe thought was a great use of inheritance for the purpose of reuse hasn’t turned out so well when it comes to maintenance.

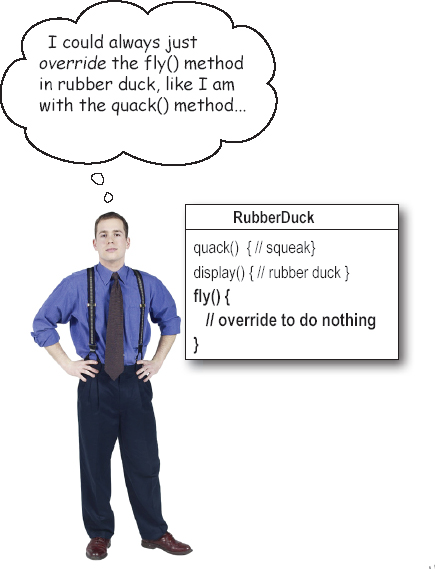

Joe thinks about inheritance...

Figure 1-10.

Figure 1-11.

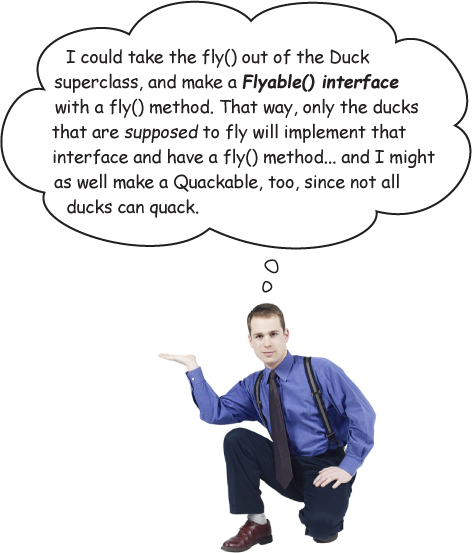

How about an interface?

Joe realized that inheritance probably wasn’t the answer, because he just got a memo that says that the executives now want to update the product every six months (in ways they haven’t yet decided on). Joe knows the spec will keep changing and he’ll be forced to look at and possibly override fly() and quack() for every new Duck subclass that’s ever added to the program... forever.

So, he needs a cleaner way to have only some (but not all) of the duck types fly or quack.

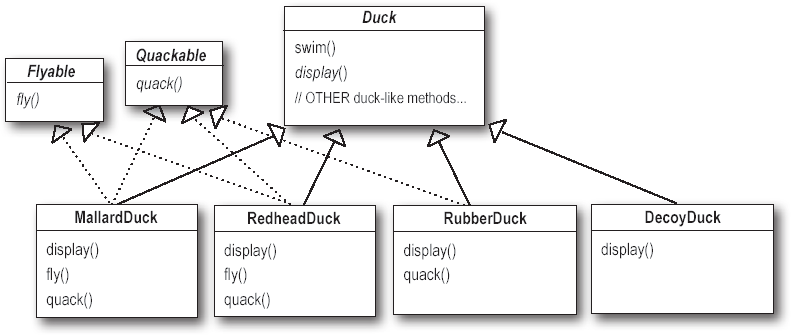

Figure 1-12.

Figure 1-13.

What do YOU think about this design?

What would you do if you were Joe?

Figure 1-14.

We know that not all of the subclasses should have flying or quacking behavior, so inheritance isn’t the right answer. But while having the subclasses implement Flyable and/or Quackable solves part of the problem (no inappropriately flying rubber ducks), it completely destroys code reuse for those behaviors, so it just creates a different maintenance nightmare. And of course there might be more than one kind of flying behavior even among the ducks that do fly...

At this point you might be waiting for a Design Pattern to come riding in on a white horse and save the day. But what fun would that be? No, we’re going to figure out a solution the old-fashioned way—by applying good OO software design principles.

Figure 1-15.

The one constant in software development

Okay, what’s the one thing you can always count on in software development?

No matter where you work, what you’re building, or what language you are programming in, what’s the one true constant that will be with you always?

Figure 1-16.

No matter how well you design an application, over time an application must grow and change or it will die.

Zeroing in on the problem...

So we know using inheritance hasn’t worked out very well, since the duck behavior keeps changing across the subclasses, and it’s not appropriate for all subclasses to have those behaviors. The Flyable and Quackable interface sounded promising at first—only ducks that really do fly will be Flyable, etc.—except Java interfaces typically have no implementation code, so no code reuse. In either case, whenever you need to modify a behavior, you’re often forced to track down and change it in all the different subclasses where that behavior is defined, probably introducing new bugs along the way!

Luckily, there’s a design principle for just this situation.

Figure 1-17.

Take what varies and “encapsulate“ it so it won’t affect the rest of your code.

The result? Fewer unintended consequences from code changes and more f lexibility in your systems!

In other words, if you’ve got some aspect of your code that is changing, say with every new requirement, then you know you’ve got a behavior that needs to be pulled out and separated from all the stuff that doesn’t change.

Here’s another way to think about this principle: take the parts that vary and encapsulate them, so that later you can alter or extend the parts that vary without affecting those that don’t.

As simple as this concept is, it forms the basis for almost every design pattern. All patterns provide a way to let some part of a system vary independently of all other parts.

Okay, time to pull the duck behavior out of the Duck classes!

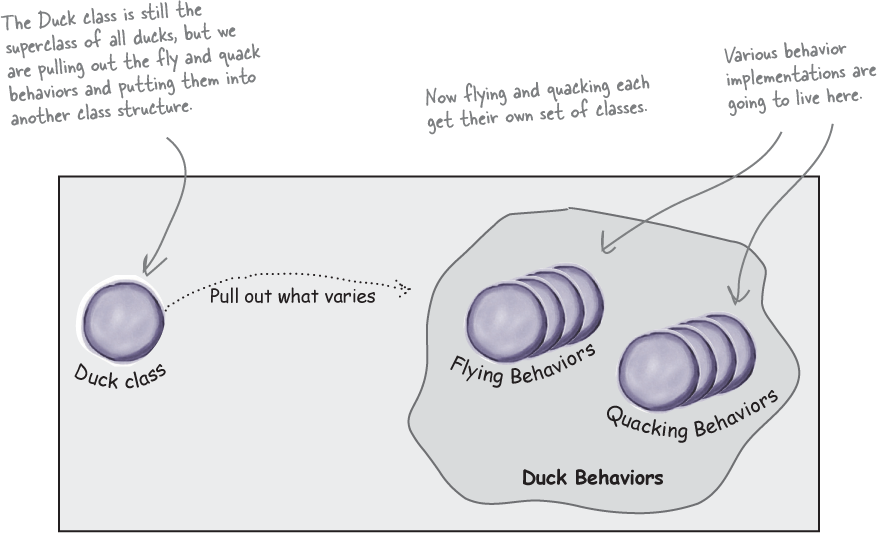

Separating what changes from what stays the same

Where do we start? As far as we can tell, other than the problems with fly() and quack(), the Duck class is working well and there are no other parts of it that appear to vary or change frequently. So, other than a few slight changes, we’re going to pretty much leave the Duck class alone.

Now, to separate the “parts that change from those that stay the same,” we are going to create two sets of classes (totally apart from Duck), one for fly and one for quack. Each set of classes will hold all the implementations of the respective behavior. For instance, we might have one class that implements quacking, another that implements squeaking, and another that implements silence.

We know that fly() and quack() are the parts of the Duck class that vary across ducks.

Note

To separate these behaviors from the Duck class, we’ll pull both methods out of the Duck class and create a new set of classes to represent each behavior.

Figure 1-18.

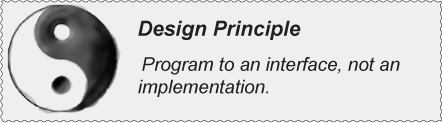

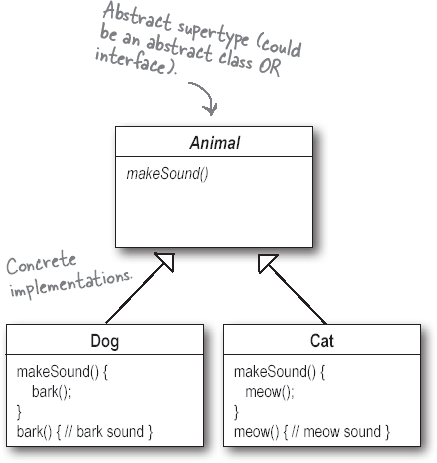

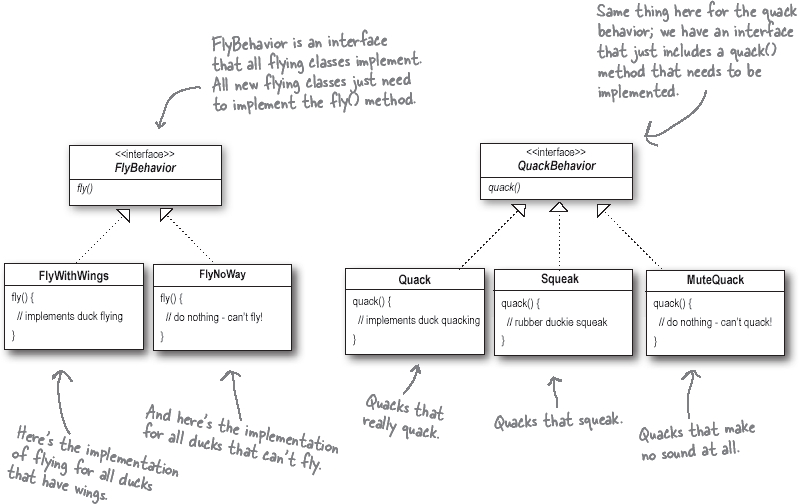

Designing the Duck Behaviors

So how are we going to design the set of classes that implement the fly and quack behaviors?

We’d like to keep things flexible; after all, it was the inflexibility in the duck behaviors that got us into trouble in the first place. And we know that we want to assign behaviors to the instances of Duck. For example, we might want to instantiate a new MallardDuck instance and initialize it with a specific type of flying behavior. And while we’re there, why not make sure that we can change the behavior of a duck dynamically? In other words, we should include behavior setter methods in the Duck classes so that we can change the MallardDuck’s flying behavior at runtime.

Given these goals, let’s look at our second design principle:

Figure 1-19.

Note

From now on, the Duck behaviors will live in a separate class—a class that implements a particular behavior interface.

Note

That way, the Duck classes won’t need to know any of the implementation details for their own behaviors.

We’ll use an interface to represent each behavior—for instance, FlyBehavior and QuackBehavior—and each implementation of a behavior will implement one of those interfaces.

So this time it won’t be the Duck classes that will implement the flying and quacking interfaces. Instead, we’ll make a set of classes whose entire reason for living is to represent a behavior (for example, “squeaking”), and it’s the behavior class, rather than the Duck class, that will implement the behavior interface.

This is in contrast to the way we were doing things before, where a behavior came either from a concrete implementation in the superclass Duck, or by providing a specialized implementation in the subclass itself. In both cases we were relying on an implementation. We were locked into using that specific implementation and there was no room for changing the behavior (other than writing more code).

With our new design, the Duck subclasses will use a behavior represented by an interface (FlyBehavior and QuackBehavior), so that the actual implementation of the behavior (in other words, the specific concrete behavior coded in the class that implements the FlyBehavior or QuackBehavior) won’t be locked into the Duck subclass.

Figure 1-20.

“Program to an interface” really means “Program to a supertype.”

Figure 1-21.

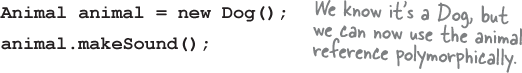

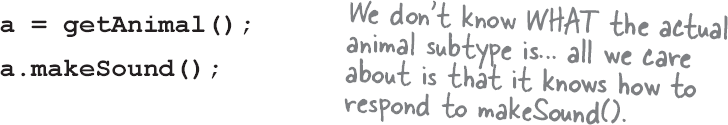

The word interface is overloaded here. There’s the concept of interface, but there’s also the Java construct interface. You can program to an interface, without having to actually use a Java interface. The point is to exploit polymorphism by programming to a supertype so that the actual runtime object isn’t locked into the code. And we could rephrase “program to a supertype” as “the declared type of the variables should be a supertype, usually an abstract class or interface, so that the objects assigned to those variables can be of any concrete implementation of the supertype, which means the class declaring them doesn’t have to know about the actual object types!”

This is probably old news to you, but just to make sure we’re all saying the same thing, here’s a simple example of using a polymorphic type—imagine an abstract class Animal, with two concrete implementations, Dog and Cat.

Programming to an implementation would be:

Figure 1-22.

But programming to an interface/supertype would be:

Figure 1-23.

Even better, rather than hardcoding the instantiation of the subtype (like new Dog()) into the code, assign the concrete implementation object at runtime:

Figure 1-24.

Figure 1-25.

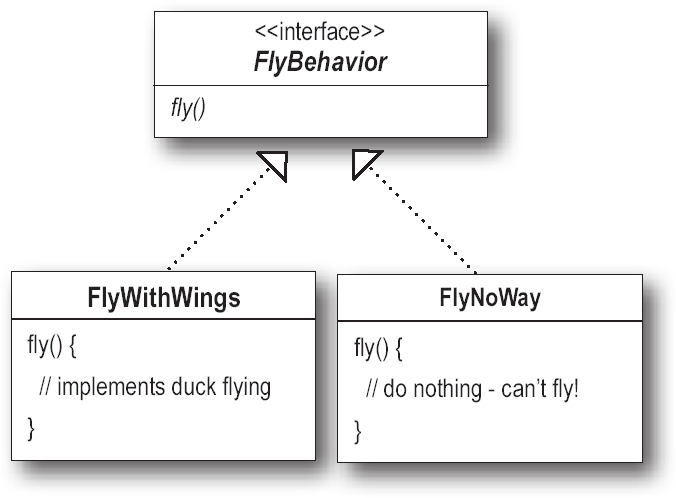

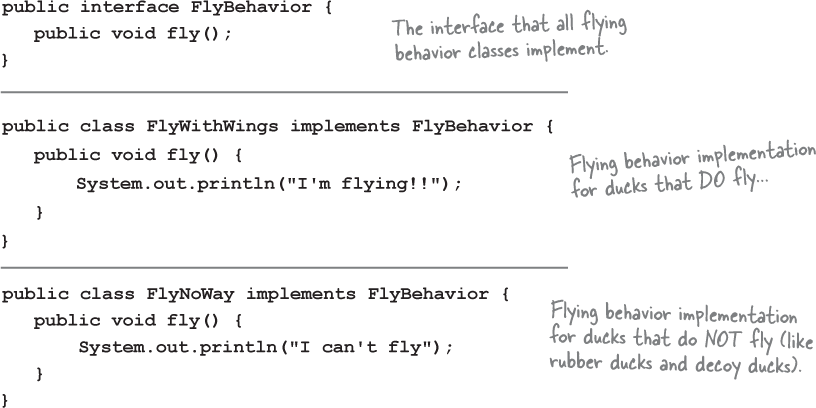

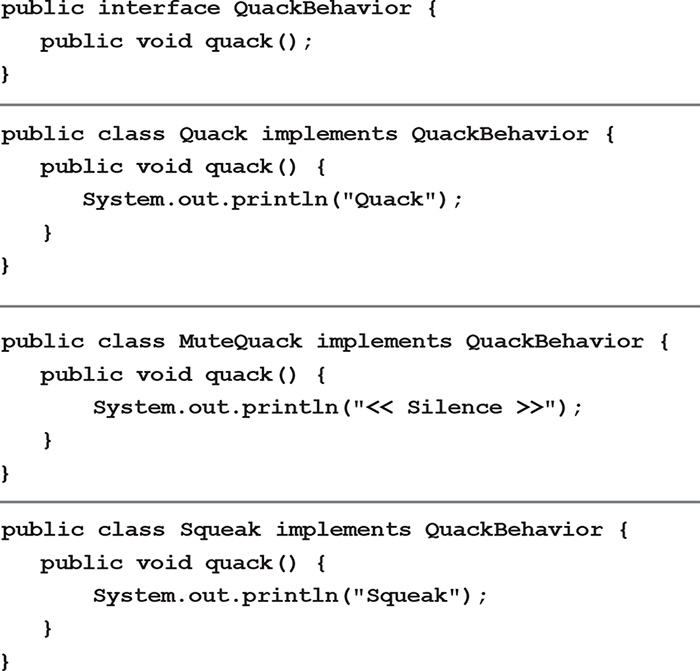

Implementing the Duck Behaviors

Here we have the two interfaces, FlyBehavior and QuackBehavior, along with the corresponding classes that implement each concrete behavior:

Figure 1-26.

Figure 1-27.

Answers:

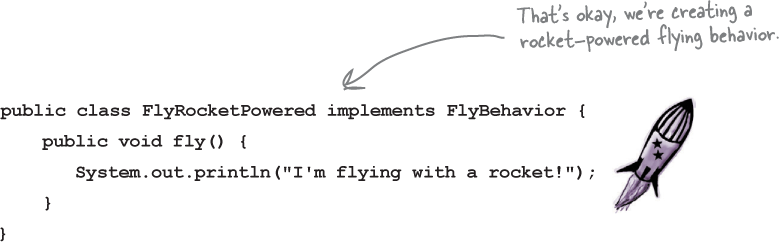

1) Create a FlyRocketPowered class that implements the FlyBehavior interface.

2) One example, a duck call (a device that makes duck sounds).

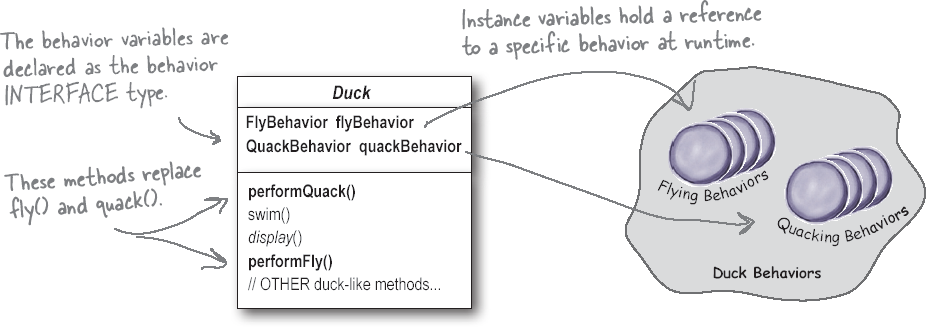

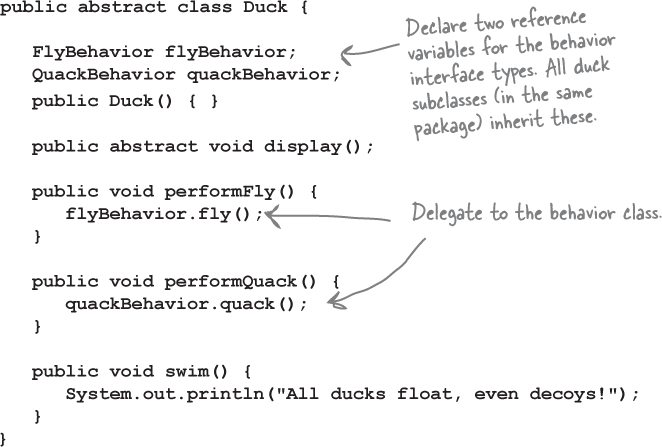

Integrating the Duck Behavior

Here’s the key: a Duck will now delegate its flying and quacking behavior, instead of using quacking and flying methods defined in the Duck class (or subclass).

Here’s how:

-

First we’ll add two instance variables of type FlyBehavior and QuackBehavior—let’s call them flyBehavior and quackBehavior. Each concrete duck object will assign to those variables a specific behavior at runtime, like FlyWithWings for flying and Squeak for quacking.

We’ll also remove the fly() and quack() methods from the Duck class (and any subclasses) because we’ve moved this behavior out into the FlyBehavior and QuackBehavior classes.

We’ll replace fly() and quack() in the Duck class with two similar methods, called performFly() and performQuack(); you’ll see how they work next.

Figure 1-28.

-

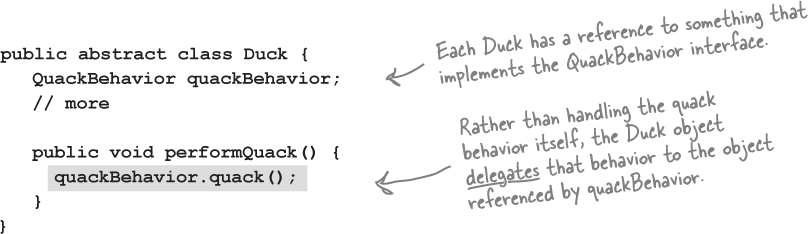

Now we implement performQuack():

Figure 1-29.

Pretty simple, huh? To perform the quack, a Duck just asks the object that is referenced by quackBehavior to quack for it. In this part of the code we don’t care what kind of object the concrete Duck is, all we care about is that it knows how to quack()!

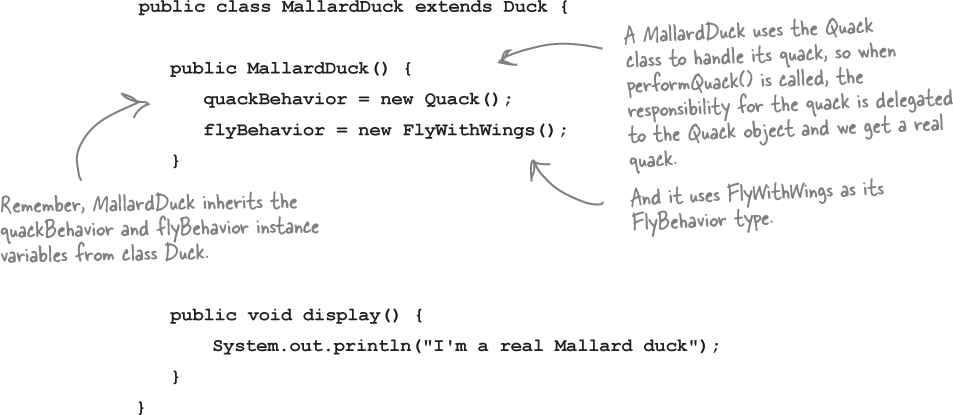

More integration...

-

Okay, time to worry about how the flyBehavior and quackBehavior instance variables are set. Let’s take a look at the MallardDuck class:

Figure 1-30.

MallardDuck’s quack is a real live duck quack, not a squeak and not a mute quack. When a MallardDuck is instantiated, its constructor initializes the MallardDuck’s inherited quackBehavior instance variable to a new instance of type Quack (a QuackBehavior concrete implementation class).

And the same is true for the duck’s flying behavior—the MallardDuck’s constructor initializes the flyBehavior instance variable with an instance of type FlyWithWings (a FlyBehavior concrete implementation class).

Figure 1-31.

Good catch, that’s exactly what we’re doing... for now.

Later in the book we’ll have more patterns in our toolbox that can help us fix it.

Still, notice that while we are setting the behaviors to concrete classes (by instantiating a behavior class like Quack or FlyWithWings and assigning it to our behavior reference variable), we could easily change that at runtime.

So, we still have a lot of flexibility here. That said, we’re doing a poor job of initializing the instance variables in a flexible way. But think about it: since the quackBehavior instance variable is an interface type, we could (through the magic of polymorphism) dynamically assign a different QuackBehavior implementation class at runtime.

Take a moment and think about how you would implement a duck so that its behavior could change at runtime. (You’ll see the code that does this a few pages from now.)

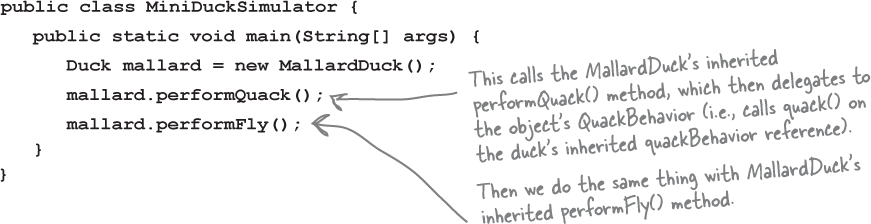

Testing the Duck code

-

Type and compile the Duck class below (Duck.java), and the MallardDuck class from two pages back (MallardDuck.java).

Figure 1-32.

-

Type and compile the FlyBehavior interface (FlyBehavior.java) and the two behavior implementation classes (FlyWithWings.java and FlyNoWay.java).

Figure 1-33.

-

Type and compile the QuackBehavior interface (QuackBehavior.java) and the three behavior implementation classes (Quack.java, MuteQuack.java, and Squeak.java).

Figure 1-34.

-

Type and compile the test class (MiniDuckSimulator.java).

Figure 1-35.

-

Run the code!

Figure 1-36.

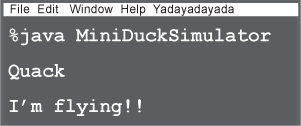

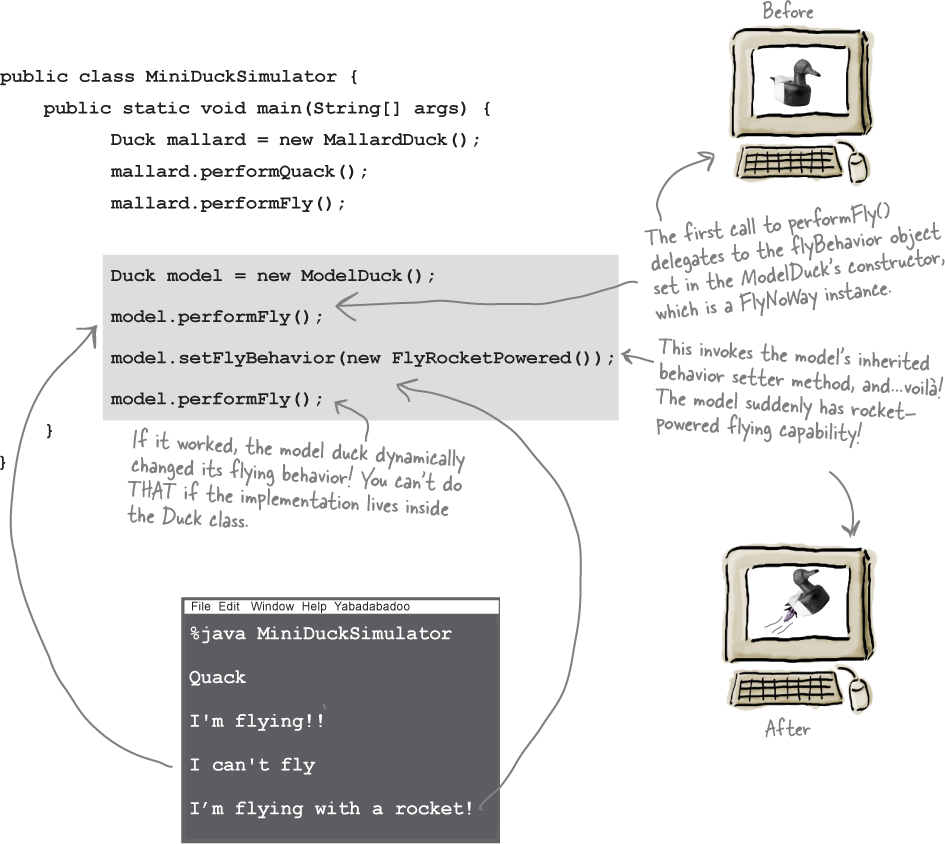

Setting behavior dynamically

What a shame to have all this dynamic talent built into our ducks and not be using it! Imagine you want to set the duck’s behavior type through a setter method on the duck subclass, rather than by instantiating it in the duck’s constructor.

-

Add two new methods to the Duck class:

Figure 1-37.

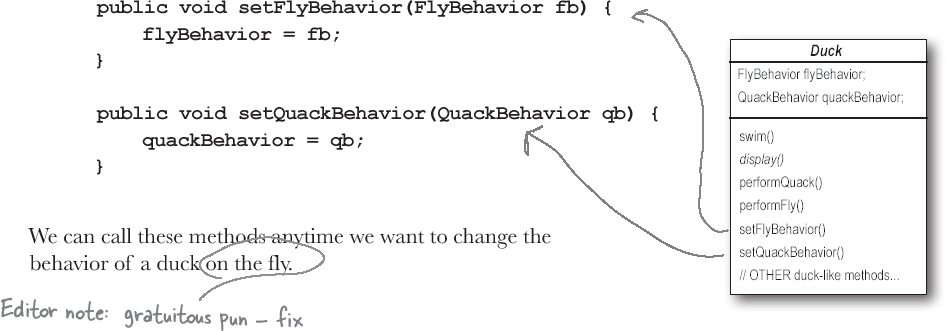

-

Make a new Duck type (ModelDuck.java).

Figure 1-38.

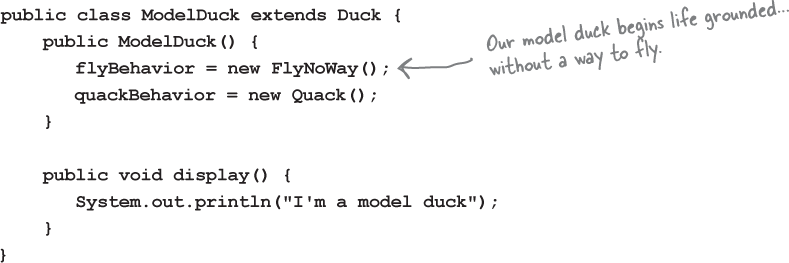

-

Make a new FlyBehavior type (FlyRocketPowered.java).

Figure 1-39.

-

Change the test class (MiniDuckSimulator.java), add the ModelDuck, and make the ModelDuck rocket-enabled.

Figure 1-40.

-

Run it!

Note

To change a duck’s behavior at runtime, just call the duck’s setter method for that behavior.

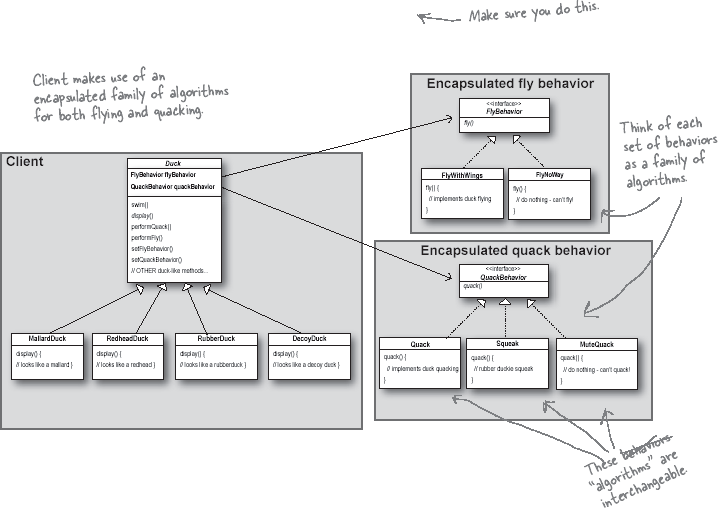

The Big Picture on encapsulated behaviors

Okay, now that we’ve done the deep dive on the duck simulator design, it’s time to come back up for air and take a look at the big picture.

Below is the entire reworked class structure. We have everything you’d expect: ducks extending Duck, fly behaviors implementing FlyBehavior, and quack behaviors implementing QuackBehavior.

Notice also that we’ve started to describe things a little differently. Instead of thinking of the duck behaviors as a set of behaviors, we’ll start thinking of them as a family of algorithms. Think about it: in the SimUDuck design, the algorithms represent things a duck would do (different ways of quacking or flying), but we could just as easily use the same techniques for a set of classes that implement the ways to compute state sales tax by different states.

Pay careful attention to the relationships between the classes. In fact, grab your pen and write the appropriate relationship (IS-A, HAS-A, and IMPLEMENTS) on each arrow in the class diagram.

Figure 1-41.

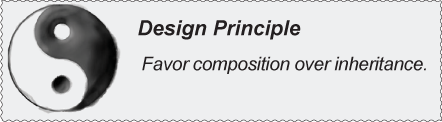

HAS-A can be better than IS-A

The HAS-A relationship is an interesting one: each duck has a FlyBehavior and a QuackBehavior to which it delegates flying and quacking.

When you put two classes together like this you’re using composition. Instead of inheriting their behavior, the ducks get their behavior by being composed with the right behavior object.

This is an important technique; in fact, it is the basis of our third design principle:

Figure 1-42.

As you’ve seen, creating systems using composition gives you a lot more flexibility. Not only does it let you encapsulate a family of algorithms into their own set of classes, but it also lets you change behavior at runtime as long as the object you’re composing with implements the correct behavior interface.

Composition is used in many design patterns and you’ll see a lot more about its advantages and disadvantages throughout the book.

Figure 1-43.

Guru and Student...

Guru: Tell me what you have learned of the Object-Oriented ways.

Student: Guru, I have learned that the promise of the object-oriented way is reuse.

Guru: Continue...

Student: Guru, through inheritance all good things may be reused and so we come to drastically cut development time like we swiftly cut bamboo in the woods.

Guru: Is more time spent on code before or after development is complete?

Student: The answer is after, Guru. We always spend more time maintaining and changing software than on initial development.

Guru: So, should effort go into reuse above maintainability and extensibility?

Student: Guru, I believe that there is truth in this.

Guru: I can see that you still have much to learn. I would like for you to go and meditate on inheritance further. As you’ve seen, inheritance has its problems, and there are other ways of achieving reuse.

Speaking of Design Patterns...

Note

The Strategy Pattern defines a family of algorithms, encapsulates each one, and makes them interchangeable. Strategy lets the algorithm vary independently from clients that use it.

Note

Use THIS definition when you need to impress friends and influence key executives.

Figure 1-44.

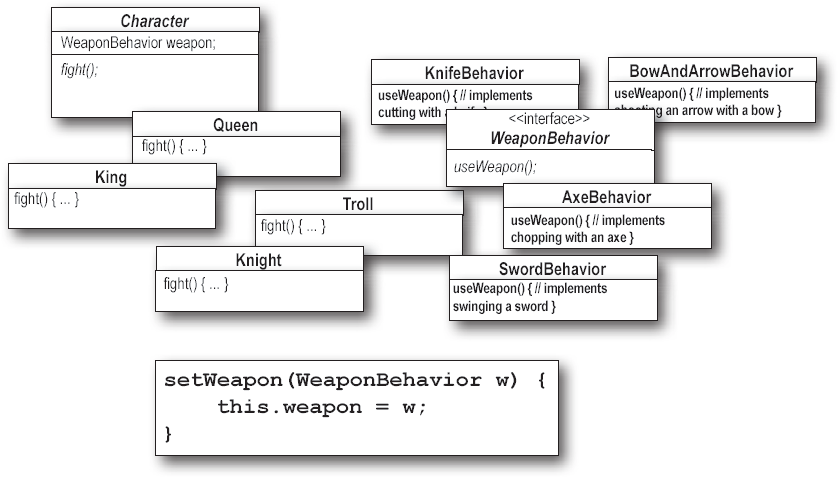

Design Puzzle

Below you’ll find a mess of classes and interfaces for an action adventure game. You’ll find classes for game characters along with classes for weapon behaviors the characters can use in the game. Each character can make use of one weapon at a time, but can change weapons at any time during the game. Your job is to sort it all out...

(Answers are at the end of the chapter.)

Your task:

-

Arrange the classes.

-

Identify one abstract class, one interface, and eight classes.

-

Draw arrows between classes.

a. Draw this kind of arrow for inheritance (“extends”).

b. Draw this kind of arrow for interface (“implements”).

c. Draw this kind of arrow for “HAS-A”.

-

Put the method setWeapon() into the right class.

Figure 1-45.

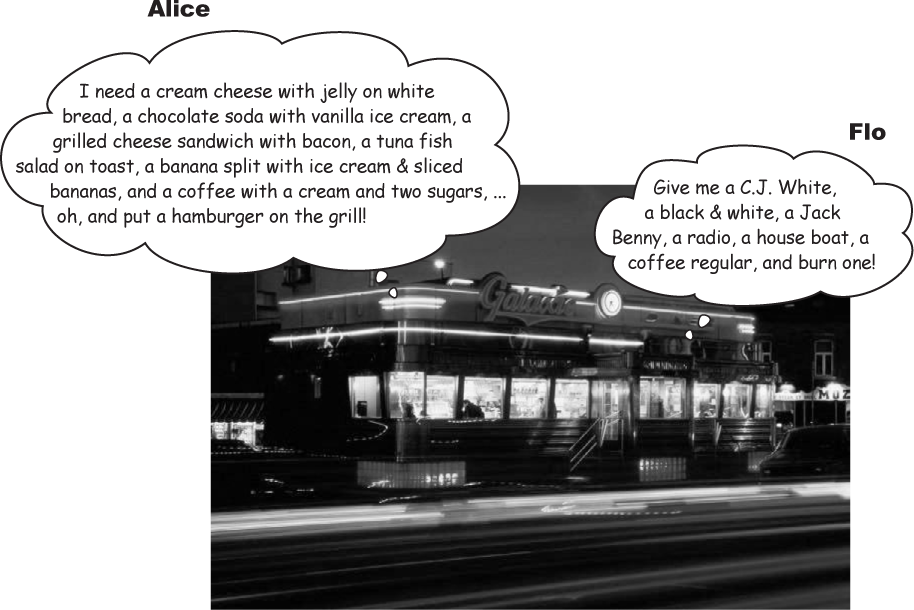

Overheard at the local diner...

Figure 1-46.

What’s the difference between these two orders? Not a thing! They’re both the same order, except Alice is using twice the number of words and trying the patience of a grumpy short-order cook.

What’s Flo got that Alice doesn’t? A shared vocabulary with the short-order cook. Not only does that make it easier to communicate with the cook, but it gives the cook less to remember because he’s got all the diner patterns in his head.

Design Patterns give you a shared vocabulary with other developers. Once you’ve got the vocabulary you can more easily communicate with other developers and inspire those who don’t know patterns to start learning them. It also elevates your thinking about architectures by letting you think at the pattern level, not the nitty-gritty object level.

Overheard in the next cubicle...

Figure 1-47.

Figure 1-48.

The power of a shared pattern vocabulary

When you communicate using patterns you are doing more than just sharing LINGO.

Shared pattern vocabularies are POWERFUL. When you communicate with another developer or your team using patterns, you are communicating not just a pattern name but a whole set of qualities, characteristics, and constraints that the pattern represents.

Note

“We’re using the Strategy Pattern to implement the various behaviors of our ducks.” This tells you the duck behavior has been encapsulated into its own set of classes that can be easily expanded and changed, even at runtime if needed.

Patterns allow you to say more with less. When you use a pattern in a description, other developers quickly know precisely the design you have in mind.

Talking at the pattern level allows you to stay “in the design” longer. Talking about software systems using patterns allows you to keep the discussion at the design level, without having to dive down to the nitty-gritty details of implementing objects and classes.

Note

How many design meetings have you been in that quickly degrade into implementation details?

Shared vocabularies can turbo-charge your development team. A team well versed in design patterns can move more quickly with less room for misunderstanding.

Note

As your team begins to share design ideas and experience in terms of patterns, you will build a community of patterns users.

Shared vocabularies encourage more junior developers to get up to speed. Junior developers look up to experienced developers. When senior developers make use of design patterns, junior developers also become motivated to learn them. Build a community of pattern users at your organization.

Note

Think about starting a patterns study group at your organization. Maybe you can even get paid while you’re learning...

How do I use Design Patterns?

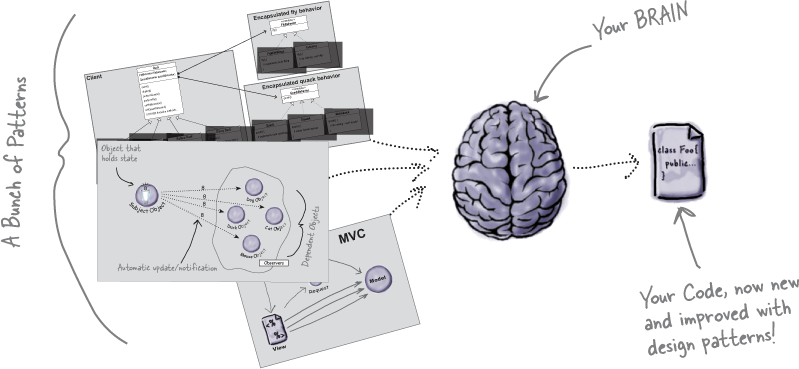

We’ve all used off-the-shelf libraries and frameworks. We take them, write some code against their APIs, compile them into our programs, and benefit from a lot of code someone else has written. Think about the Java APIs and all the functionality they give you: network, GUI, IO, etc. Libraries and frameworks go a long way towards a development model where we can just pick and choose components and plug them right in. But... they don’t help us structure our own applications in ways that are easier to understand, more maintainable and flexible. That’s where Design Patterns come in.

Design patterns don’t go directly into your code, they first go into your BRAIN. Once you’ve loaded your brain with a good working knowledge of patterns, you can then start to apply them to your new designs, and rework your old code when you find it’s degrading into an inflexible mess.

Figure 1-49.

Figure 1-50.

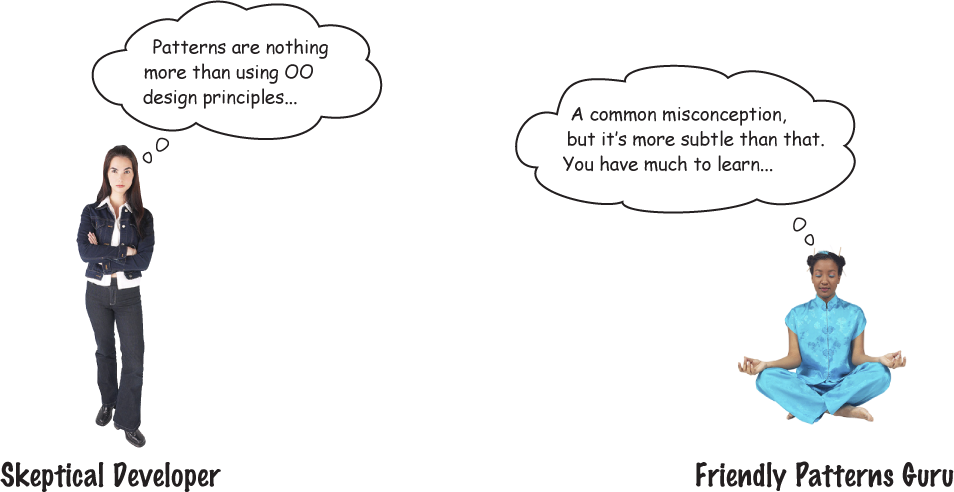

Developer: Okay, hmm, but isn’t this all just good object-oriented design; I mean as long as I follow encapsulation and I know about abstraction, inheritance, and polymorphism, do I really need to think about Design Patterns? Isn’t it pretty straightforward? Isn’t this why I took all those OO courses? I think Design Patterns are useful for people who don’t know good OO design.

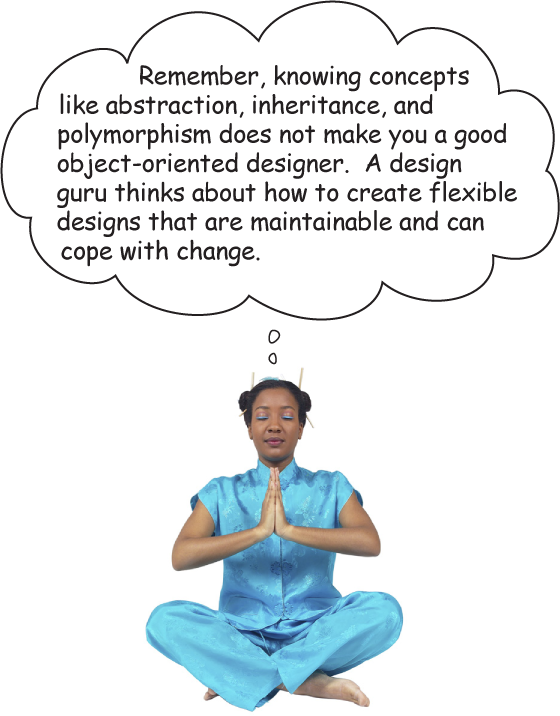

Guru: Ah, this is one of the true misunderstandings of object-oriented development: that by knowing the OO basics we are automatically going to be good at building flexible, reusable, and maintainable systems.

Developer: No?

Guru: No. As it turns out, constructing OO systems that have these properties is not always obvious and has been discovered only through hard work.

Developer: I think I’m starting to get it. These, sometimes non-obvious, ways of constructing object-oriented systems have been collected...

Guru: ...yes, into a set of patterns called Design Patterns.

Developer: So, by knowing patterns, I can skip the hard work and jump straight to designs that always work?

Guru: Yes, to an extent, but remember, design is an art. There will always be tradeoffs. But, if you follow well thought-out and time-tested design patterns, you’ll be way ahead.

Developer: What do I do if I can’t find a pattern?

Figure 1-51.

Guru: There are some object-oriented principles that underlie the patterns, and knowing these will help you to cope when you can’t find a pattern that matches your problem.

Developer: Principles? You mean beyond abstraction, encapsulation, and...

Guru: Yes, one of the secrets to creating maintainable OO systems is thinking about how they might change in the future, and these principles address those issues.

Figure 1-52.

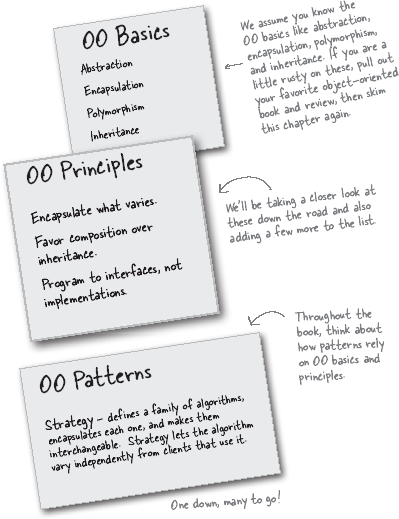

Tools for your Design Toolbox

You’ve nearly made it through the first chapter! You’ve already put a few tools in your OO toolbox; let’s make a list of them before we move on to Chapter 2.

Figure 1-53.

Figure 1-54.

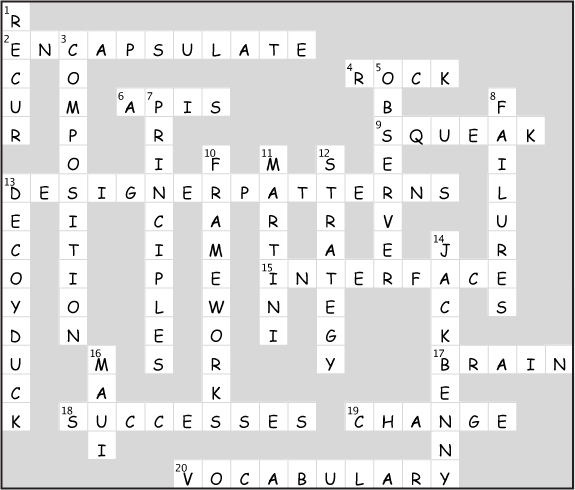

Design Patterns Crossword

Let’s give your right brain something to do.

It’s your standard crossword; all of the solution words are from this chapter.

Figure 1-55.

ACROSS

2. ________ what varies.

4. Design patterns __________.

6. Java IO, Networking, Sound.

9. Rubber ducks make a __________.

13. Bartender thought they were called.

15. Program to this, not an implementation.

17. Patterns go into your _________.

18. Learn from the other guy’s ___________.

19. Development constant.

20. Patterns give us a shared ____________.

DOWN

1. Patterns _______ in many applications.

3. Favor this over inheritance.

5. Dan was thrilled with this pattern.

7. Most patterns follow from OO _________.

8. Not your own __________.

10. High level libraries.

11. Joe’s favorite drink.

12. Pattern that fixed the simulator.

13. Duck that can’t quack.

14. Grilled cheese with bacon.

15. Duck demo was located here.

Figure 1-56.

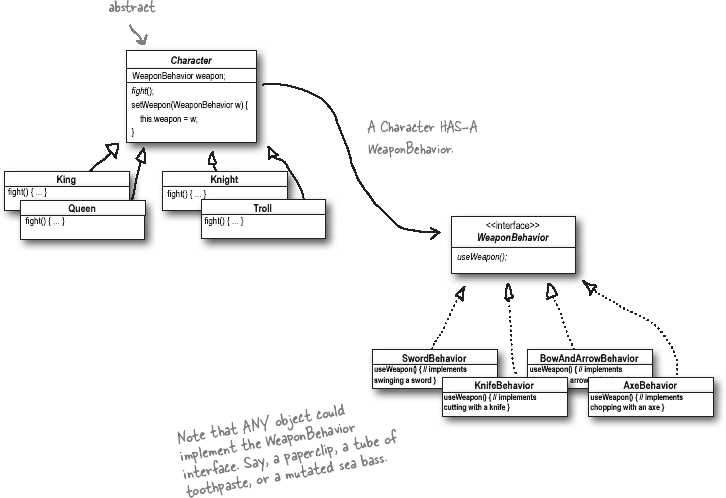

Design Puzzle Solution

Character is the abstract class for all the other characters (King, Queen, Knight, and Troll), while WeaponBehavior is an interface that all weapon behaviors implement. So all actual characters and weapons are concrete classes.

To switch weapons, each character calls the setWeapon() method, which is defined in the Character superclass. During a fight the useWeapon() method is called on the current weapon set for a given character to inflict great bodily damage on another character.

Figure 1-57.

Figure 1-58.

Design Patterns Crossword Solution

Figure 1-59.

Chapter 2. The Observer Pattern: Keeping your Objects in the Know

You don’t want to miss out when something interesting happens, do you? We’ve got a pattern that keeps your objects in the know when something they care about happens. It’s the Observer Pattern. It is one of the most commonly used design patterns, and it’s incredibly useful. We’re going to look at all kinds of interesting aspects of Observer, like its one-to-many relationships and loose coupling. And, with those concepts in mind, how can you help but be the life of the Patterns Party?

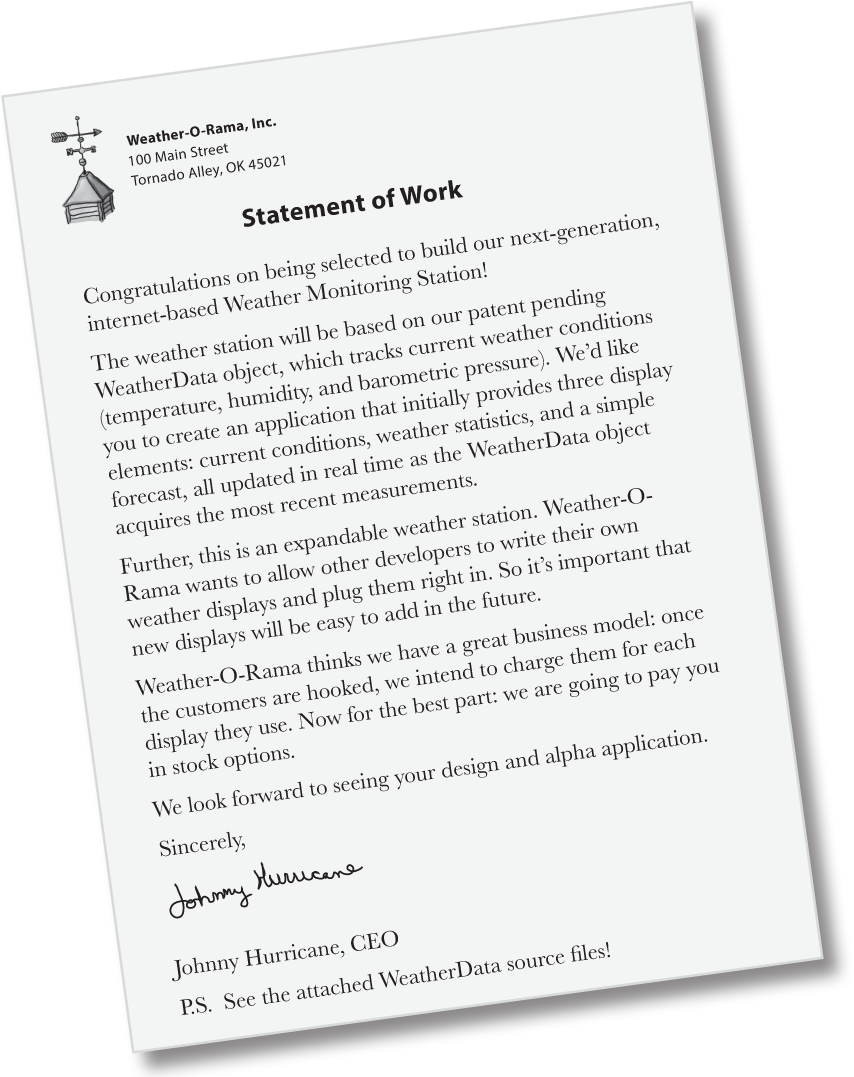

Congratulations!

Your team has just won the contract to build Weather-O-Rama, Inc.’s next-generation, internet-based Weather Monitoring Station.

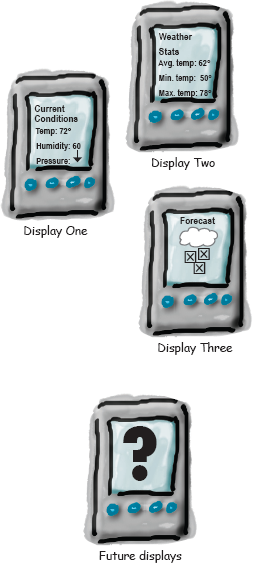

The Weather Monitoring application overview

Let’s take a look at the Weather Monitoring application we need to deliver—both what Weather-O-Rama is giving us, and what we’re going to need to build, or extend. The system has three components: the weather station (the physical device that acquires the actual weather data), the WeatherData object (that tracks the data coming from the Weather Station and updates the displays), and the display that shows users the current weather conditions:

The WeatherData object was written by Weather-O-Rama and knows how to talk to the physical Weather Station to get updated weather data. We’ll need to adapt the WeatherData object so that it knows how to update the display. Hopefully Weather-O-Rama has given us hints for how to do this in the source code. Remember, we’re responsible for implementing three different display elements: Current Conditions (shows temperature, humidity, and pressure), Weather Statistics, and a simple Forecast.

So, our job, if we choose to accept it, is to create an app that uses the WeatherData object to update three displays for current conditions, weather stats, and a forecast.

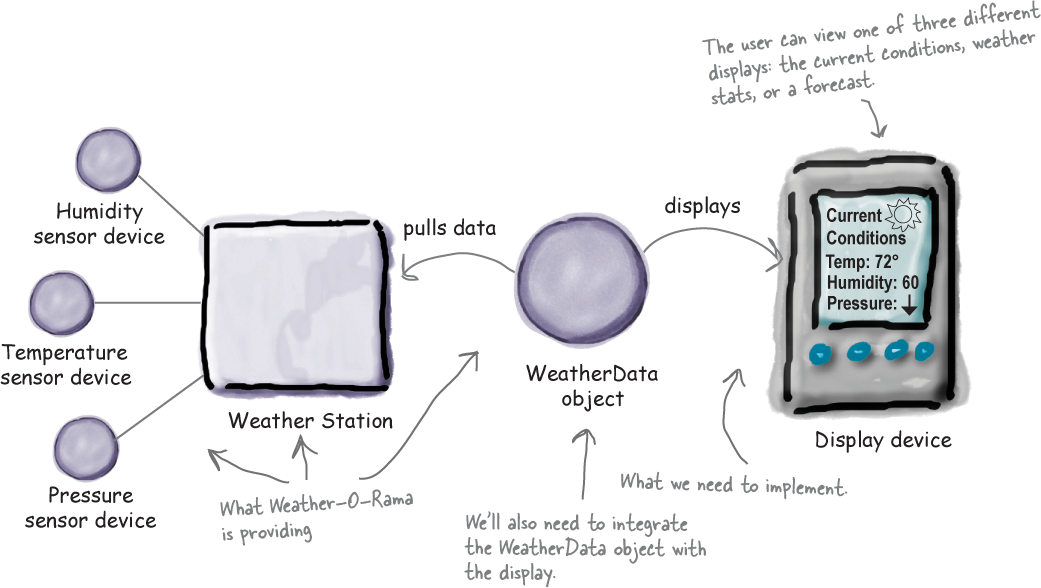

Unpacking the WeatherData class

Let’s check out the source code attachments that Johnny Hurricane, the CEO, sent over. We’ll start with the WeatherData class:

So, our job is to alter the measurementsChanged() method so that it updates the three displays for current conditions, weather stats, and forecast.

Our Goal

We know we need to implement a display and then to have the WeatherData update that display each time it has new values, or, in other words, each time the measurementsChanged() method is called. But how? Let’s think through what we’re trying to acheive:

We know the WeatherData class has getter methods for three measurement values: temperature, humidity, and barometric pressure.

We know the measurementsChanged() method is called any time new weather measurement data is available. (Again, we don’t know or care how this method is called; we just know that it is called.)

We’ll need to implement three display elements that use the weather data: a current conditions display, a statistics display, and a forecast display. These displays must be updated as often as the WeatherData has new measurements.

To update the displays, we’ll add code to the measurementsChanged() method.

Stretch Goal

But let’s also think about the future—remember the constant in software development? Change. We expect, if successful, there will be more than three displays in the future, in fact, why not create a marketplace for additional displays? So, how about we build in:

Expandability—other developers may want to create new custom displays. Why not allow users to add (or remove) as many display elements as they want to the application. Currently, we know about the initial three display types (current conditions, statistics, and forecast) but we expect a vibrant marketplace for new displays in the future.

Taking a first, misguided SWAG at the Weather Station

Here’s a first implementation possibility—as we’ve discussed we’re going to add our code to the measurementsChanged() method in the WeatherData class:

What’s wrong with our implementation anyway?

Think back to all those Chapter 1 concepts and principles—which are we violating, and which are we not? Think in particular about the effects of change on this code. Let’s work through our thinking as we look at the code:

Good idea. Let’s take a look at Observer, then come back and figure out how to apply it to the Weather Monitoring app.

Meet the Observer Pattern

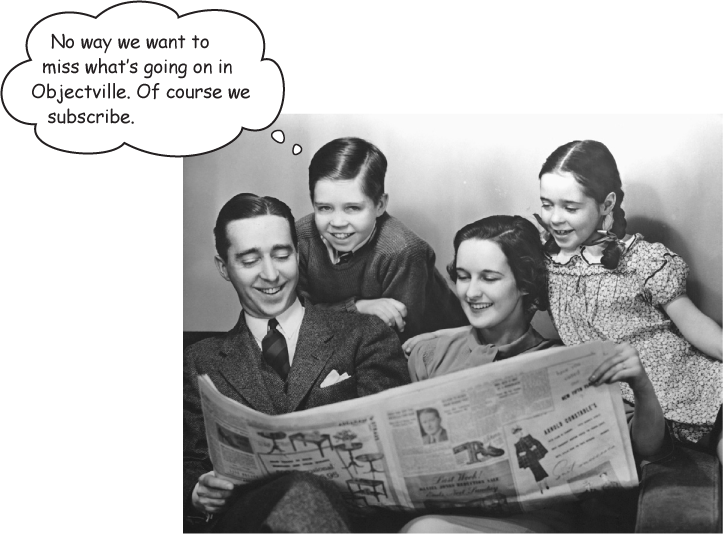

You know how newspaper or magazine subscriptions work:

A newspaper publisher goes into business and begins publishing newspapers.

You subscribe to a particular publisher, and every time there’s a new edition it gets delivered to you. As long as you remain a subscriber, you get new newspapers.

You unsubscribe when you don’t want papers anymore, and they stop being delivered.

While the publisher remains in business, people, hotels, airlines, and other businesses constantly subscribe and unsubscribe to the newspaper.

Publishers + Subscribers = Observer Pattern

If you understand newspaper subscriptions, you pretty much understand the Observer Pattern, only we call the publisher the SUBJECT and the subscribers the OBSERVERS.

Let’s take a closer look:

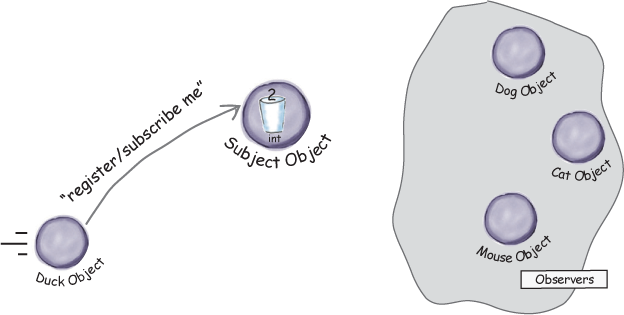

A day in the life of the Observer Pattern

A Duck object comes along and tells the Subject that he wants to become an observer.

Duck really wants in on the action; those ints Subject is sending out whenever its state changes look pretty interesting...

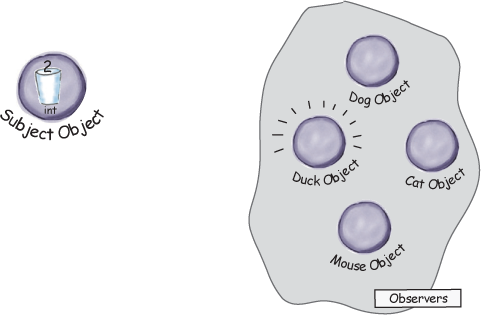

The Duck object is now an official observer.

Duck is psyched... he’s on the list and is waiting with great anticipation for the next notification so he can get an int.

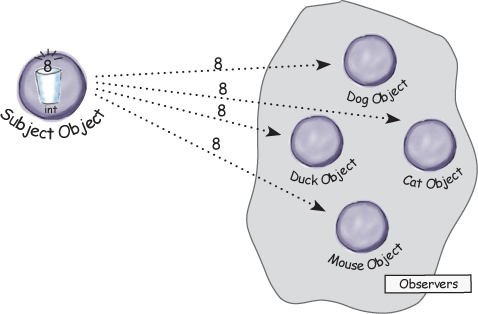

The Subject gets a new data value!

Now Duck and all the rest of the observers get a notification that the Subject has changed.

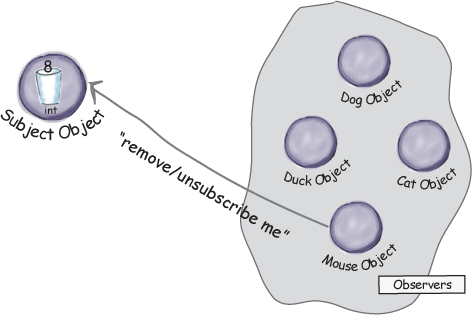

The Mouse object asks to be removed as an observer.

The Mouse object has been getting ints for ages and is tired of it, so he decides it’s time to stop being an observer.

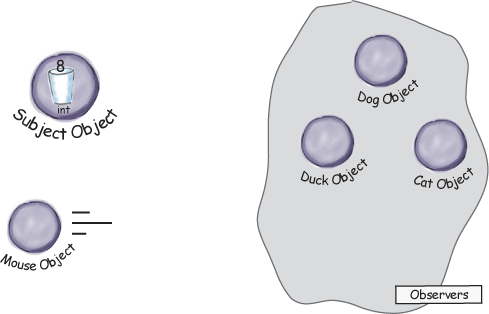

Mouse is outta here!

The Subject acknowledges the Mouse’s request and removes him from the set of observers.

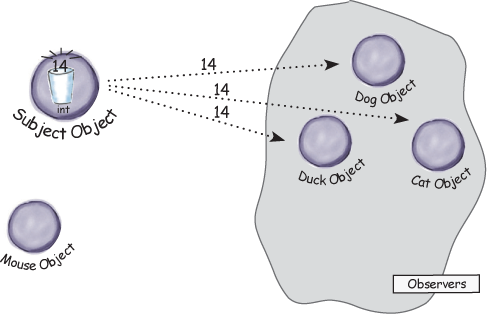

The Subject has another new int.

All the observers get another notification, except for the Mouse who is no longer included. Don’t tell anyone, but the Mouse secretly misses those ints... maybe he’ll ask to be an observer again some day

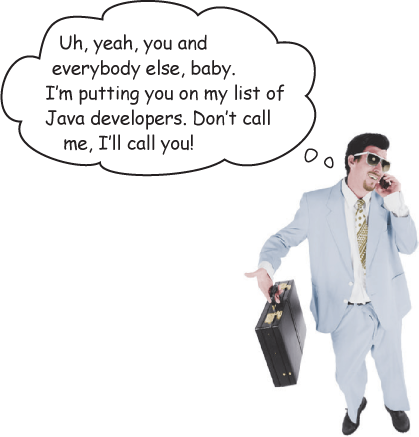

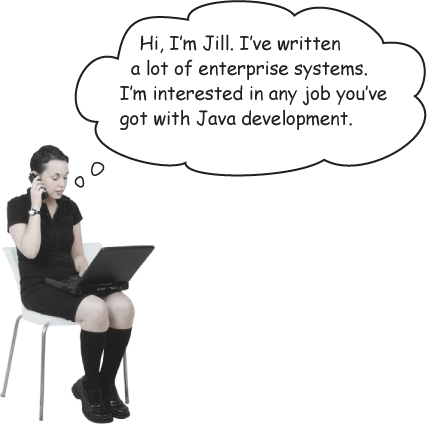

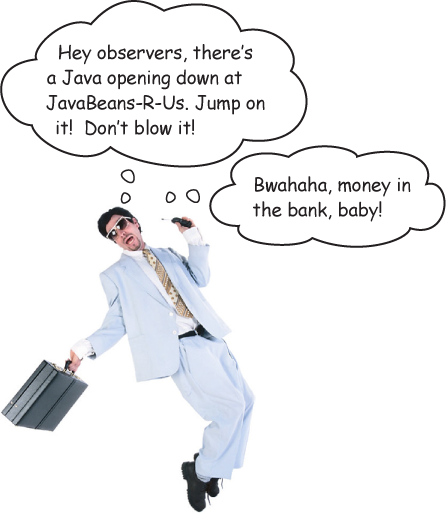

Five-minute drama: a subject for observation

In today’s skit, two enterprising software developers encounter a real live head hunter...

Software Developer #1

Headhunter/Subject

Software Developer #2

Subject

Meanwhile, for Lori and Jill life goes on; if a Java job comes along, they’ll get notified. After all, they are observers.

Subject

Observer

Observer

Subject

Two weeks later...

Jill’s loving life, and no longer an observer. She’s also enjoying the nice fat signing bonus that she got because the company didn’t have to pay a headhunter.

But what has become of our dear Lori? We hear she’s beating the headhunter at his own game. She’s not only still an observer, she’s got her own call list now, and she is notifying her own observers. Lori’s a subject and an observer all in one.

The Observer Pattern defined

A newspaper subscription, with its publisher and subscribers, is a good way to visualize the pattern.

In the real world, however, you’ll typically see the Observer Pattern defined like this:

Note

The Observer Pattern defines a one-to-many dependency between objects so that when one object changes state, all of its dependents are notified and updated automatically.

Let’s relate this definition to how we’ve been thinking about the pattern:

Note

The Observer Pattern defines a one-to-many relationship between a set of objects.

When the state of one object changes, all of its dependents are notified.

The subject and observers define the one-to-many relationship. We have one subject, who notifies many observers when something in the subject changes. The observers are dependent on the subject—when the subject’s state changes, the observers are notified.

As you’ll discover, there are a few different ways to implement the Observer Pattern, but most revolve around a class design that includes Subject and Observer interfaces.

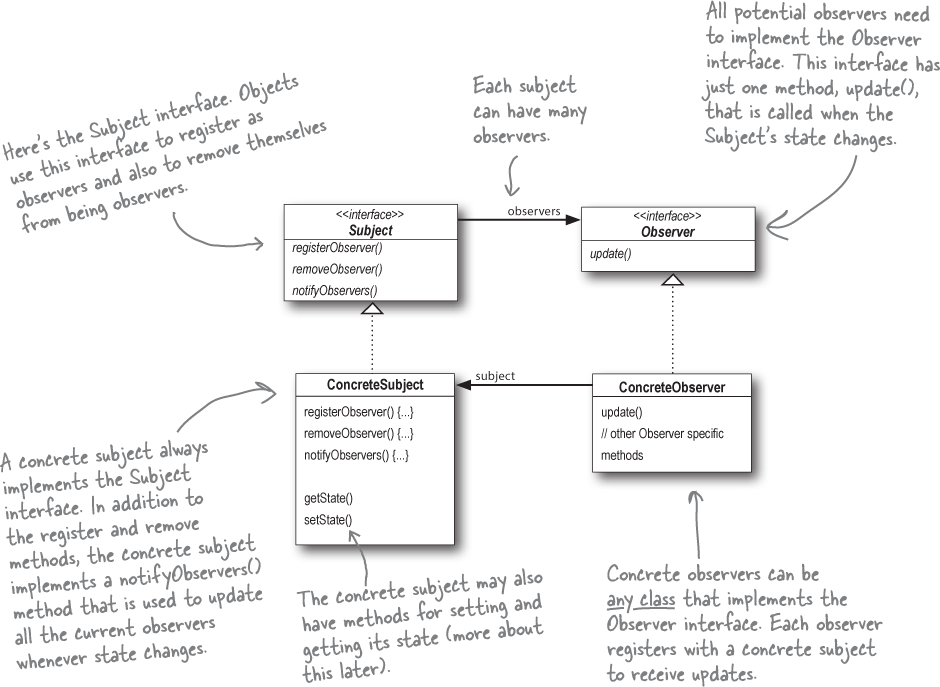

The Observer Pattern: the Class Diagram

Let’s take a look at the structure of the Observer Pattern, complete with its Subject and Observer classes. Here’s the class diagram:

Guru and Student...

Guru: Have we talked about loose coupling?

Student: Guru, I do not recall such a discussion.

Guru: Is a tightly woven basket stiff or flexible?

Student: Stiff, Guru.

Guru: And do stiff or flexible baskets tear or break less easily?

Student: A flexible basket tends to break less easily.

Guru: And in our software, might our designs break less easily if our objects are less tightly bound together?

Student: Guru, I see the truth of it. But what does it mean for objects to be less tightly bound?

Guru: We like to call it, loosely coupled.

Student: Ah!

Guru: We say a object is tightly coupled to another object when it is too dependent on that object.

Student: So a loosely coupled object can’t depend on another object?

Guru: Think of nature; all living things depend on each other. Likewise, all objects depend on other objects. But a loosely coupled object doesn’t know or care too much about the details of another object.

Student: But Guru, that doesn’t sound like a good quality. Surely not knowing is worse than knowing.

Guru: You are doing well in your studies, but you have much to learn. By not knowing too much about other objects we can create designs that can handle change better. Designs that have more flexibility, like the less tightly woven basket.

Student: Of course, I am sure you are right. Could you give me an example?

Guru: That is enough for today.

The Power of Loose Coupling

When two objects are loosely coupled, they can interact, but they typically have very little knowledge of each other. As we’re going to see, loosely coupled designs often give us a lot of flexibility (more on that in a bit). And, as it turns out, the Observer Pattern is a great example of loose coupling. Let’s walk through all the ways the pattern achieves loose coupling:

First, the only thing the subject knows about an observer is that it implements a certain interface (the Observer interface). It doesn’t need to know the concrete class of the observer, what it does, or anything else about it.

We can add new observers at any time. Because the only thing the subject depends on is a list of objects that implement the Observer interface, we can add new observers whenever we want. In fact, we can replace any observer at runtime with another observer and the subject will keep purring along. Likewise, we can remove observers at any time.

We never need to modify the subject to add new types of observers. Let’s say we have a new concrete class come along that needs to be an observer. We don’t need to make any changes to the subject to accommodate the new class type; all we have to do is implement the Observer interface in the new class and register as an observer. The subject doesn’t care; it will deliver notifications to any object that implements the Observer interface.

We can reuse subjects or observers independently of each other. If we have another use for a subject or an observer, we can easily reuse them because the two aren’t tightly coupled.

Changes to either the subject or an observer will not affect the other. Because the two are loosely coupled, we are free to make changes to either, as long as the objects still meet their obligations to implement the subject or observer interfaces.

Note

Loosely coupled designs allow us to build flexible OO systems that can handle change because they minimize the interdependency between objects.

Cubicle conversation

Back to the Weather Station project. Your teammates have already begun thinking through the problem...

Mary: Well, it helps to know we’re using the Observer Pattern.

Sue: Right... but how do we apply it?

Mary: Hmm. Let’s look at the definition again:

The Observer Pattern defines a one-to-many dependency between objects so that when one object changes state, all its dependents are notified and updated automatically.

Mary: That actually makes some sense when you think about it. Our WeatherData class is the “one” and our “many” is the various display elements that use the weather measurements.

Sue: That’s right. The WeatherData class certainly has state... that’s the temperature, humidity, and barometric pressure, and those definitely change.

Mary: Yup, and when those measurements change, we have to notify all the display elements so they can do whatever it is they are going to do with the measurements.

Sue: Cool, I now think I see how the Observer Pattern can be applied to our Weather Station problem.

Mary: There are still a few things to consider that I’m not sure I understand yet.

Sue: Like what?

Mary: For one thing, how do we get the weather measurements to the display elements?

Sue: Well, looking back at the picture of the Observer Pattern, if we make the WeatherData object the subject, and the display elements the observers, then the displays will register themselves with the WeatherData object in order to get the information they want, right?

Mary: Yes... and once the Weather Station knows about a display element, then it can just call a method to tell it about the measurements.

Sue: We gotta remember that every display element can be different... so I think that’s where having a common interface comes in. Even though every component has a different type, they should all implement the same interface so that the WeatherData object will know how to send them the measurements.

Mary: I see what you mean. So every display will have, say, an update() method that WeatherData will call.

Sue: And update() is defined in a common interface that all the elements implement...

Designing the Weather Station

How does this diagram compare with yours?

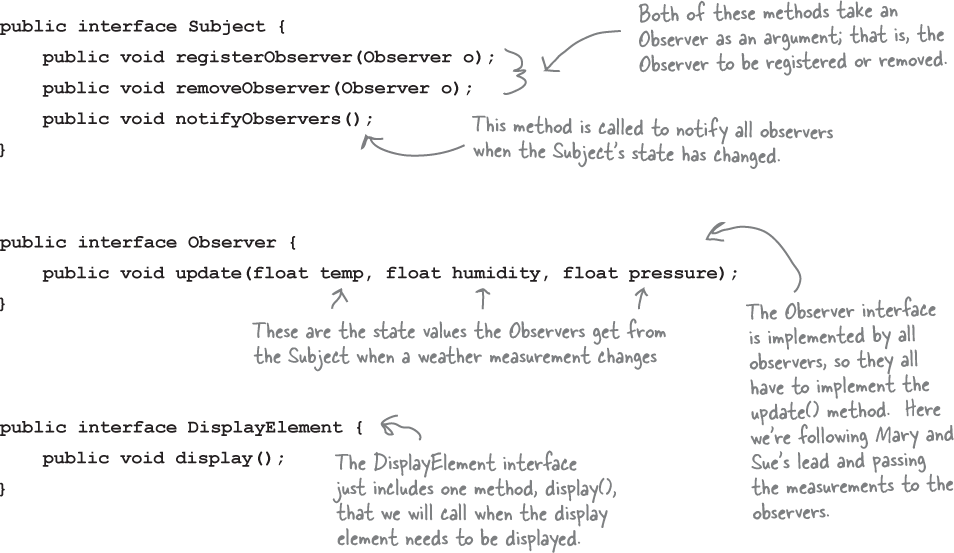

Implementing the Weather Station

Alright we’ve had some great thinking from Mary and Sue (from a few pages back) and we’ve got a diagram that details the overall structure of our classes. So, let’s get our implemention of the weather station underway. Let’s start with the interfaces:

Implementing the Subject interface in WeatherData

Remember our first attempt at implementing the WeatherData class at the beginning of the chapter? You might want to refresh your memory. Now it’s time to go back and do things with the Observer Pattern in mind:

Note

REMEMBER: we don’t provide import and package statements in the code listings. Get the complete source code from http://wickedlysmart.com/head-first-design-patterns/.

Now, let’s build those display elements

Now that we’ve got our WeatherData class straightened out, it’s time to build the Display Elements. Weather-O-Rama ordered three: the current conditions display, the statistics display, and the forecast display. Let’s take a look at the current conditions display; once you have a good feel for this display element, check out the statistics and forecast displays in the code directory. You’ll see they are very similar.

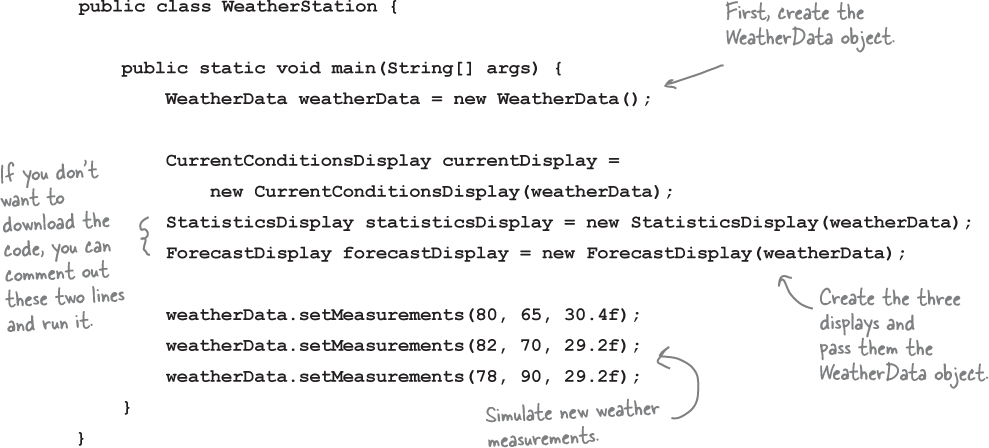

Power up the Weather Station

First, let’s create a test harness.

The Weather Station is ready to go. All we need is some code to glue everything together. We’ll be adding some more displays and generalizing things in a bit. For now, here’s our first attempt:

Run the code and let the Observer Pattern do its magic.

Tonight’s talk: A Subject and Observer spar over the right way to get state information to the Observer.

| Subject: | Observer: |

|---|---|

| I’m glad we’re finally getting a chance to chat in person. | |

| Really? I thought you didn’t care much about us Observers. | |

| Well, I do my job, don’t I? I always tell you what’s going on... Just because I don’t really know who you are doesn’t mean I don’t care. And besides, I do know the most important thing about you—you implement the Observer interface. | |

| Yeah, but that’s just a small part of who I am. Anyway, I know a lot more about you... | |

| Oh yeah, like what? | |

| Well, you’re always passing your state around to us Observers so we can see what’s going on inside you. Which gets a little annoying at times... | |

| Well, excuuuse me. I have to send my state with my notifications so all you lazy Observers will know what happened! | |

| Okay, wait just a minute here; first, we’re not lazy, we just have other stuff to do in between your oh-so-important notifications, Mr. Subject, and second, why don’t you let us come to you for the state we want rather than pushing it out to just everyone? | |

| Well... I guess that might work. I’d have to open myself up even more, though, to let all you Observers come in and get the state that you need. That might be kind of dangerous. I can’t let you come in and just snoop around looking at everything I’ve got. | |

| Why don’t you just write some public getter methods that will let us pull out the state we need? | |

| Yes, I could let you pull my state. But won’t that be less convenient for you? If you have to come to me every time you want something, you might have to make multiple method calls to get all the state you want. That’s why I like push better... then you have everything you need in one notification. | |

| Don’t be so pushy! There are so many different kinds of us Observers, there’s no way you can anticipate everything we need. Just let us come to you to get the state we need. That way, if some of us only need a little bit of state, we aren’t forced to get it all. It also makes things easier to modify later. Say, for example, you expand yourself and add some more state. If you use pull, you don’t have to go around and change the update calls on every observer; you just need to change yourself to allow more getter methods to access our additional state. | |

| Well as I like to say, don’t call us, we’ll call you! But, I’ll give it some thought. | |

| I won’t hold my breath. | |

| You never know, hell could freeze over. | |

| I see, always the wise guy... | |

| Indeed. |

Looking for the Observer Pattern in the Wild

The Observer Pattern is one of the most common patterns in use, and you’ll find plenty of examples of the pattern being used in many libraries and frameworks. If we look at the Java Development Kit (JDK) for instance, both the JavaBeans and Swing libraries make use of the Observer Pattern. The pattern’s not limited to Java either; it’s used in JavaScript’s events and in Cocoa and Swift’s Key-Value Observing protocol, to name a couple of other examples. One of the advantages of knowing design patterns is recognizing and quickly understanding the design movitation in your favorite libraries. Let’s take a quick diversion into the Swing library to see how Observer is used.

The Swing library

You probably already know that Swing is Java’s GUI toolkit for user interfaces. One of the most basic components of that toolkit is the JButton class. If you look up JButton’s superclass, AbstractButton, you’ll find that it has a lot of add/remove listener methods. These methods allow you to add and remove observers—or, as they are called in Swing, listeners—to listen for various types of events that occur on the Swing component. For instance, an ActionListener lets you “listen in” on any types of actions that might occur on a button, like a button press. You’ll find various types of listeners all over the Swing API.

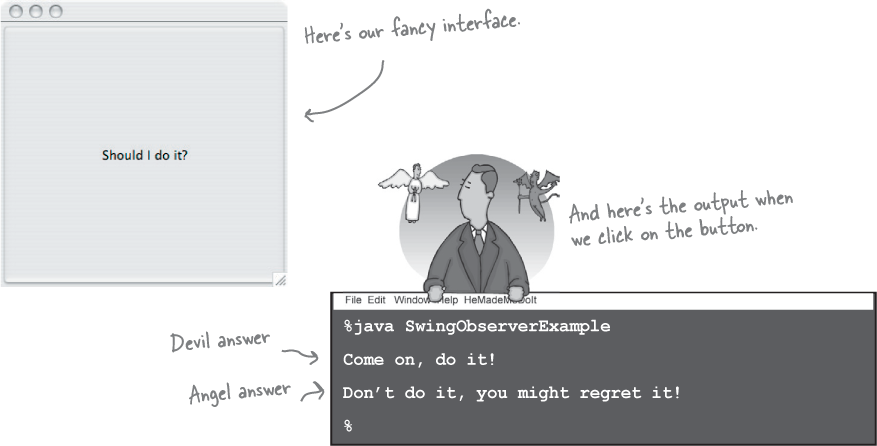

A little life-changing application

Okay, our application is pretty simple. You’ve got a button that says “Should I do it?” and when you click on that button the listeners (observers) get to answer the question in any way they want. We’re implementing two such listeners, called the AngelListener and the DevilListener. Here’s how the application behaves:

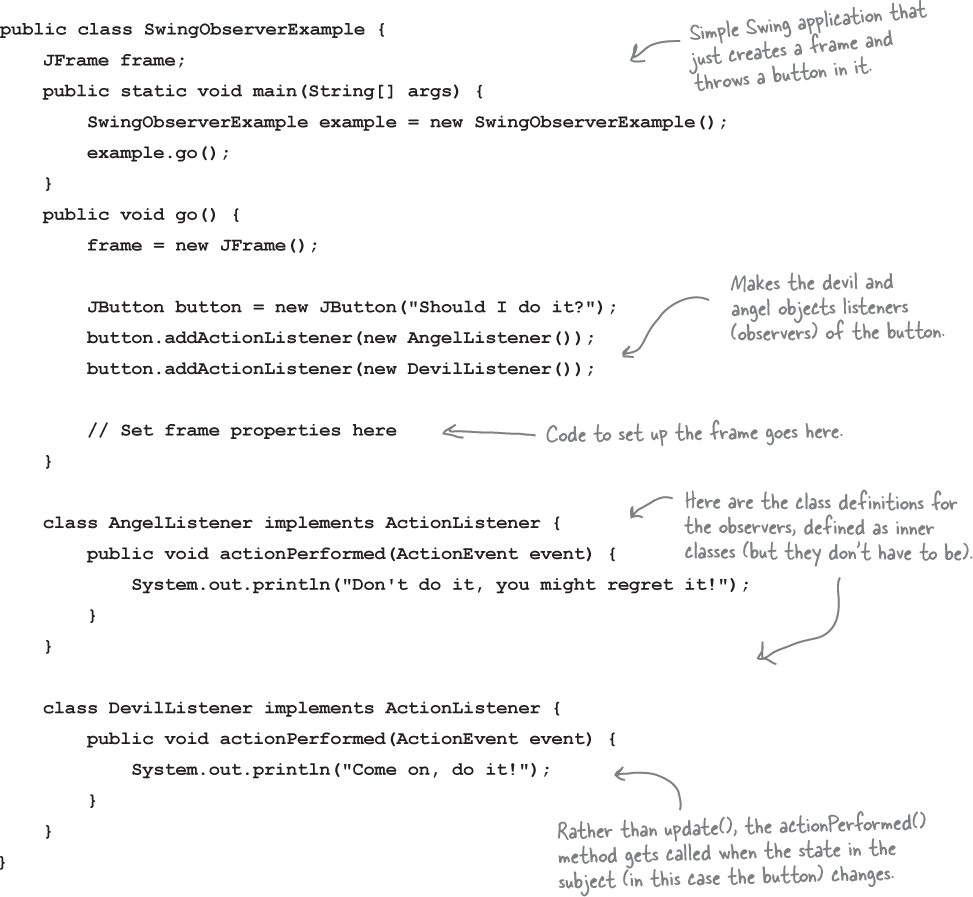

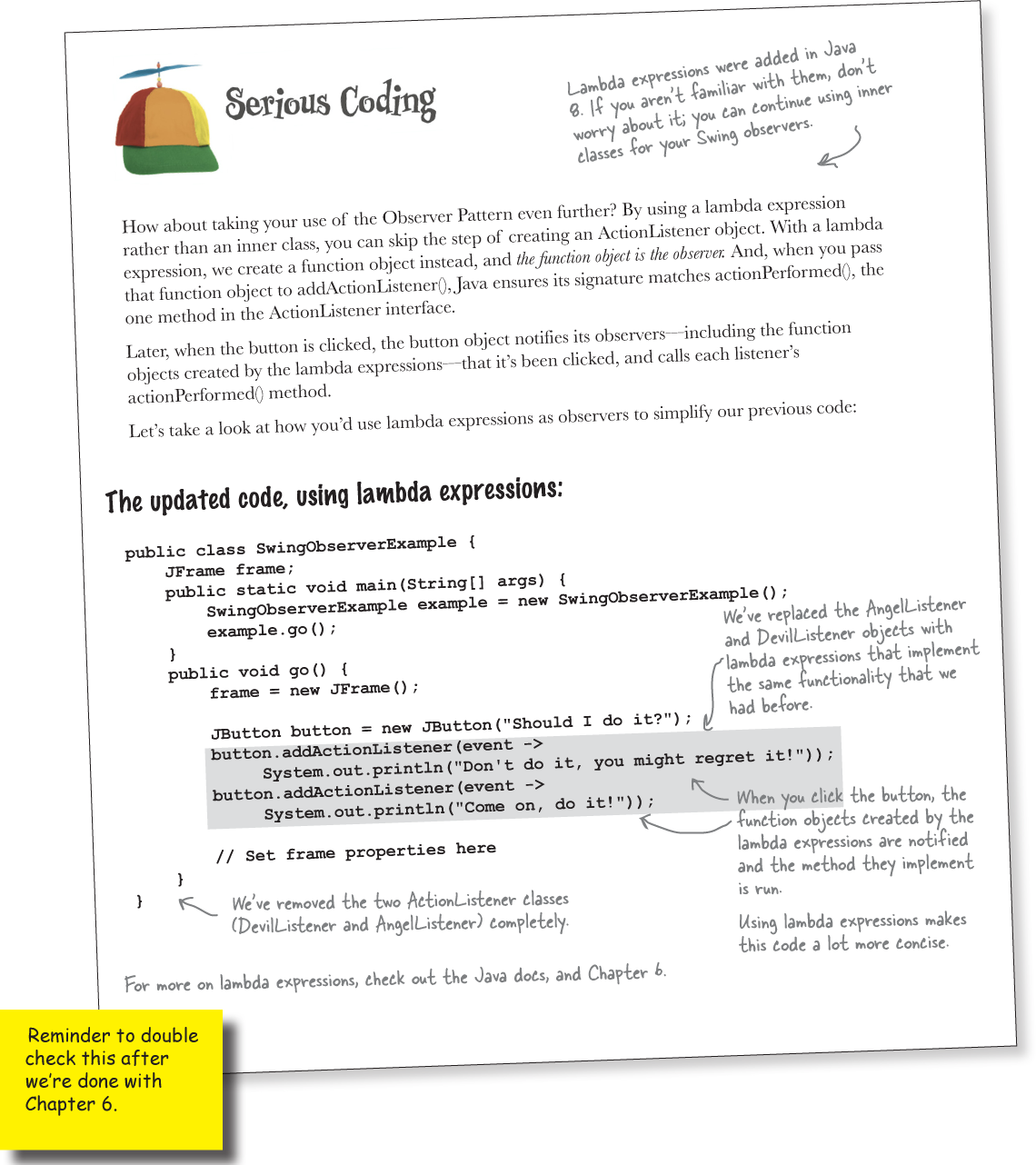

Coding the life-changing application

This life-changing application requires very little code. All we need to do is create a JButton object, add it to a JFrame and set up our listeners. We’re going to use inner classes for the listeners, which is a common technique in Swing programming. If you aren’t up on inner classes or Swing, you might want to review the “Getting GUI” chapter of Head First Java.

That’s a good idea.

In our current Weather Station design, we are pushing all three pieces of data to the update() method in the displays, even if the displays don’t need all these values. That’s okay, but what if Weather-O-Rama adds another data value later, like wind speed? Then we’ll have to change all the update() methods in all the displays, even if most of them don’t need or want the wind speed data.

Now, whether we pull or push the data tot the Observer is an implementation detail, but in a lot of cases it makes sense to let Observers retrieve the data they need rather than passing more and more data to the Observers through the update() method. After all, over time, this is an area that may change and grow unwieldy. And, we know CEO Johnny Hurricane is going to want to expand the Weather Station and sell more displays, so let’s take another pass at the design and see if we can make it even easier to expand in the future.

Updating the Weather Station code to allow Observers to pull the data they need is a pretty straight forward exercise. All we need to do is make sure the Subject has getter methods for its data, and then change our Observers to use them to pull the data that’s appropriate for their needs. Let’s do that.

Meanwhile back at Weather-O-Rama

There’s another way of handling the data in the Subject: we can rely on the Observers to pull it from the Subject as needed. Right now, when the Subject’s data changes, we push the new values for temperature, humidity, and pressure to the Observers, by passing that data in the call to update().

Let’s set things up so that when an Observer is notified of a change, it calls getter methods on the Subject to pull the values it needs.

To switch to using pull, we need to make a few small changes to our existing code.

For the Subject to send notifications...

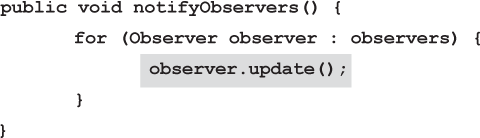

We’ll modify the notifyObservers() method in WeatherData to call the method update() in the Observers with no arguments:

For an Observer to receive notifications...

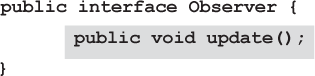

Then we’ll modify the Observer interface, changing the signature of the update() method so that it has no parameters:

And finally, we modify each concrete Observer to change the signature of its respective update() methds and get the weather data from the Subject using the WeatherData’s getter methods. Here’s the new code for the CurrentConditionsDisplay class:

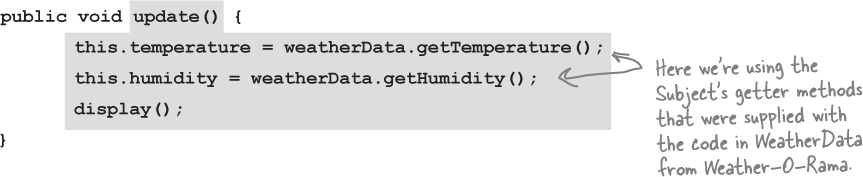

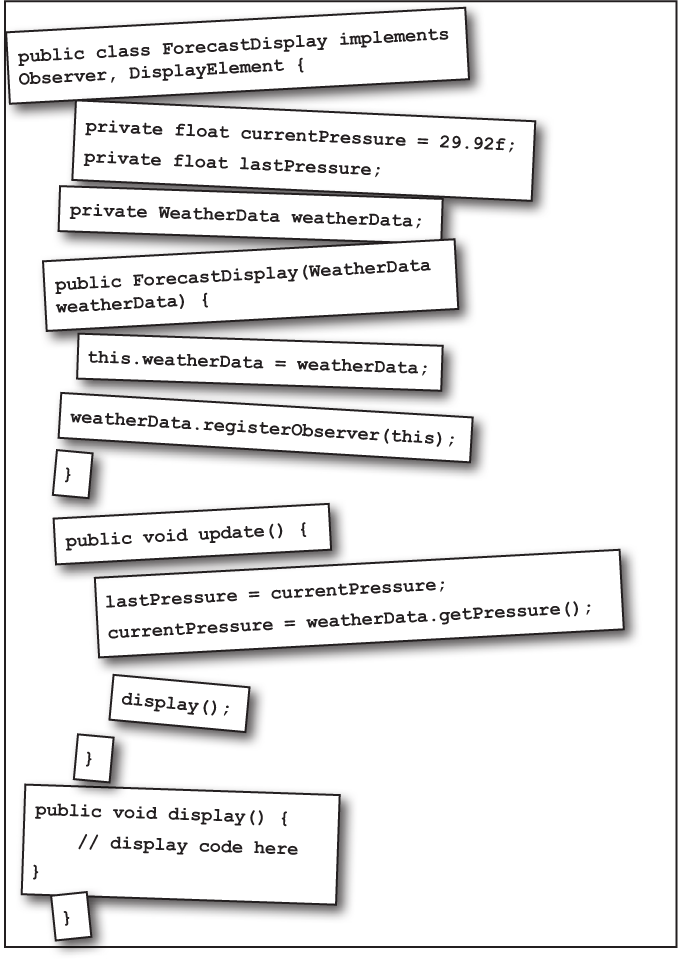

Code Magnets

The ForecastDisplay class is all scrambled up on the fridge. Can you reconstruct the code snippets to make it work? Some of the curly braces fell on the floor and they were too small to pick up, so feel free to add as many of those as you need!

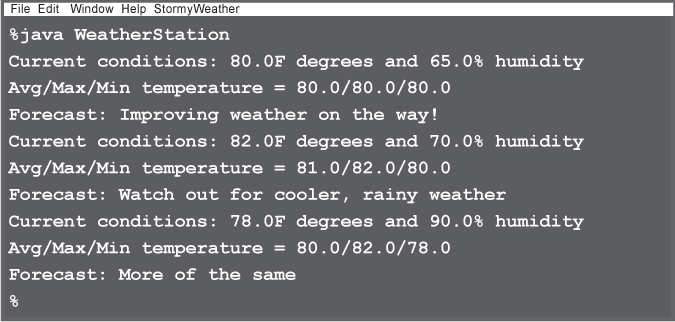

Test Drive the new code

Okay, you’ve got one more display to update, the Avg/Min/Max display, go ahead and do that now!

Just to be sure, let’s run the new code...

Tools for your Design Toolbox

Welcome to the end of Chapter 2. You’ve added a few new things to your OO toolbox...

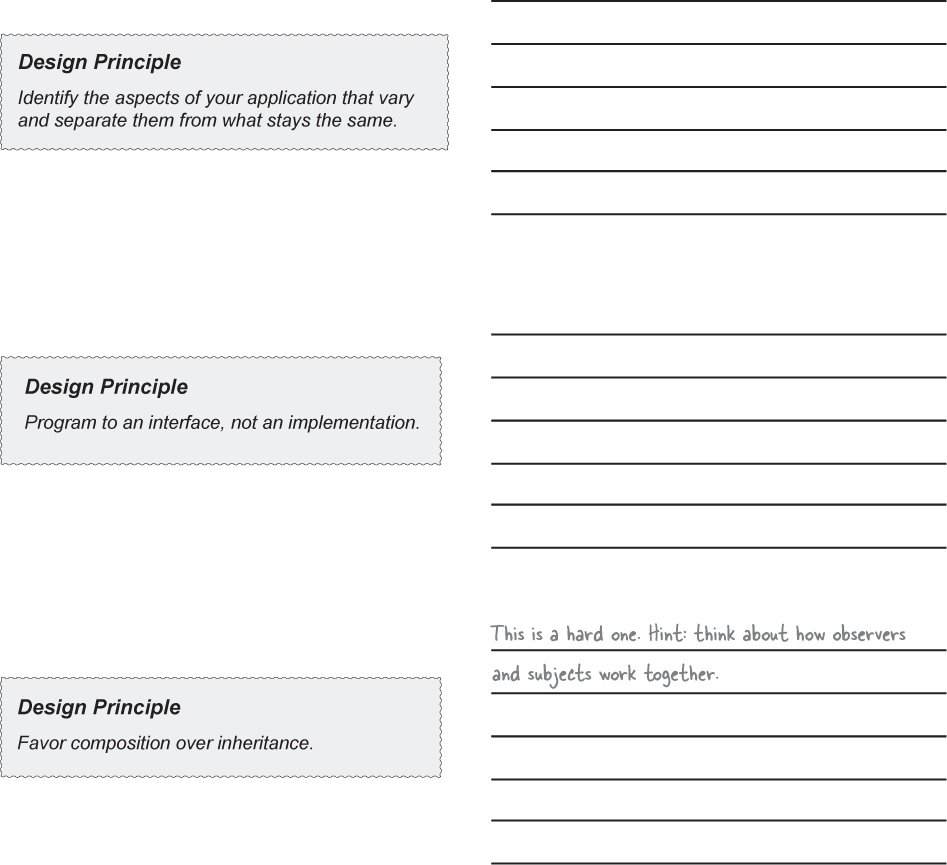

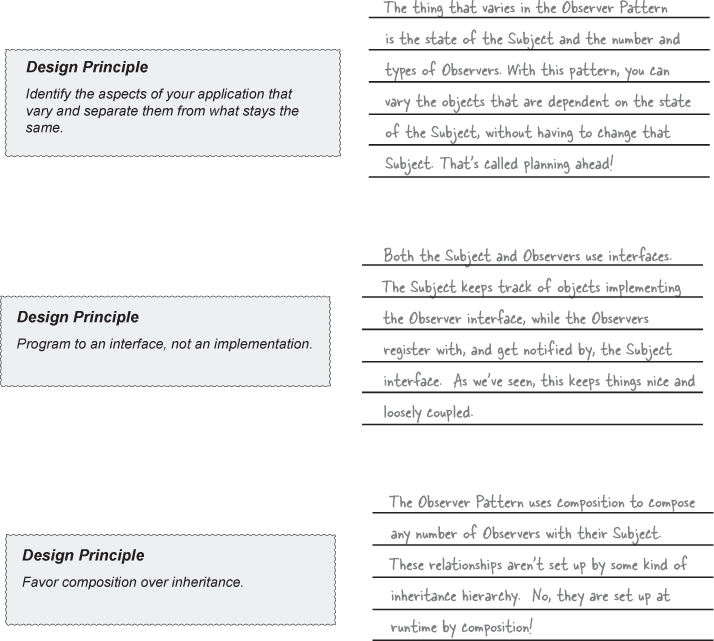

Design Principle Challenge

For each design principle, describe how the Observer Pattern makes use of the principle.

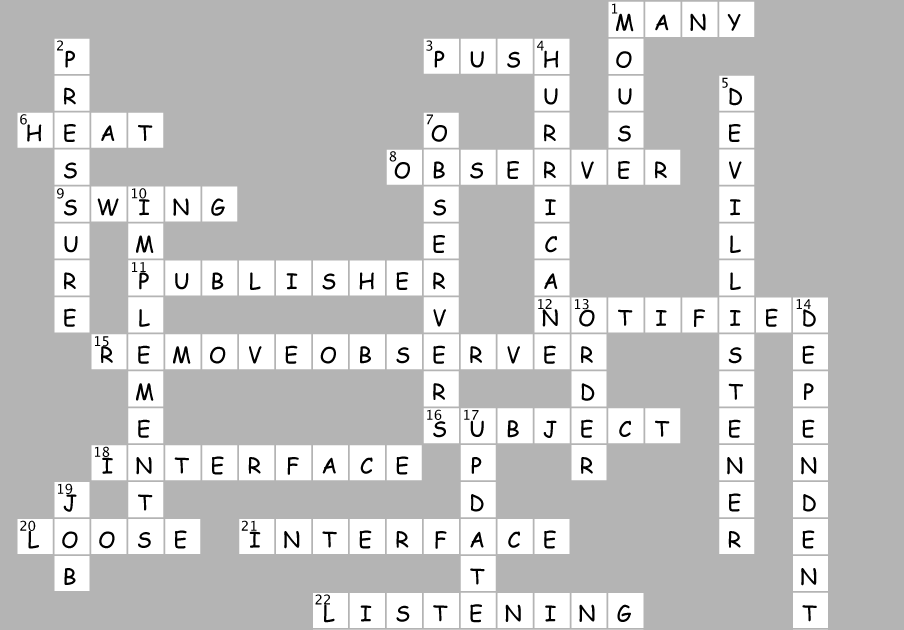

Design Patterns Crossword

Time to give your right brain something to do again! All of the solution words are from Chapter 1 & Chapter 2.

ACROSS

1. One Subject likes to talk to _______ observers.

3. Subject initially wanted to _________ all the data to Observer.

6. CEO almost forgot the ________ index display.

8. CurrentConditionsDisplay implements this interface.

9. Java framework with lots of Observers.

11. A Subject is similar to a __________.

12. Observers like to be ___________ when something new happens.

15. How to get yourself off the Observer list.

16. Ron was both an Observer and a _________.

18. Subject is an ______.

20. You want to keep your coupling ________.

21. Program to an __________ not an implementation.

22. Devil and Angel are _________ to the button.

DOWN

1. He didn’t want any more ints, so he removed himself.

2. Temperature, humidity and __________.

4. Weather-O-Rama’s CEO named after this kind of storm.

5. He says you should go for it.

7. The Subject doesn’t have to know much about the _____.

10. The WeatherData class __________ the Subject interface.

13. Don’t count on this for notification.

14. Observers are______ on the Subject.

17. Implement this method to get notified.

19. Jill got one of her own.

Design Principle Challenge Solution

Code Magnets Solution

The ForecastDisplay class is all scrambled up on the fridge. Can you reconstruct the code snippets to make it work? Some of the curly braces fell on the floor and they were too small to pick up, so feel free to add as many of those as you need! Here’s our solution.

Design Patterns Crossword Solution

About the Author(s)

John Doe does some interesting stuff...

Settings

Theme

Ask about this book

Ask anything about this book.