- Preface: Invalidating Axioms

- 1. Introduction

- I. Foundations

- 2. Architectural Thinking

- 3. Modularity

- 4. Architecture Characteristics Defined

- 5. Identifying Architectural Characteristics

- 6. Measuring and Governing Architecture Characteristics

- 7. Scope of Architecture Characteristics

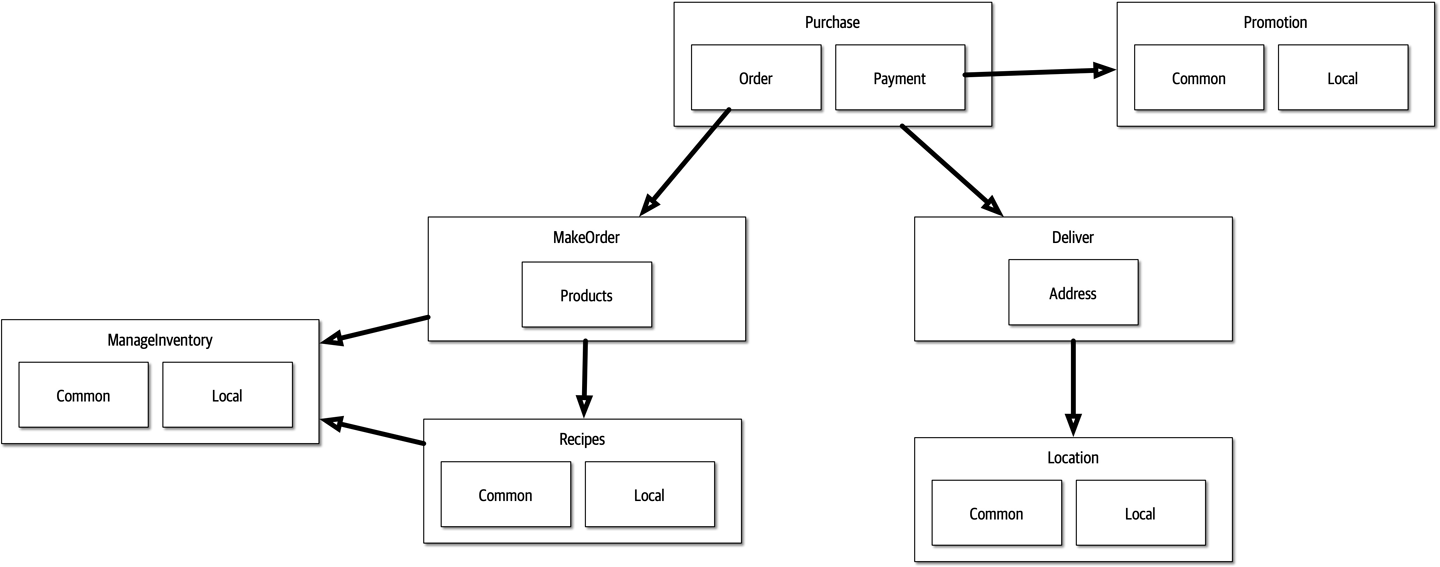

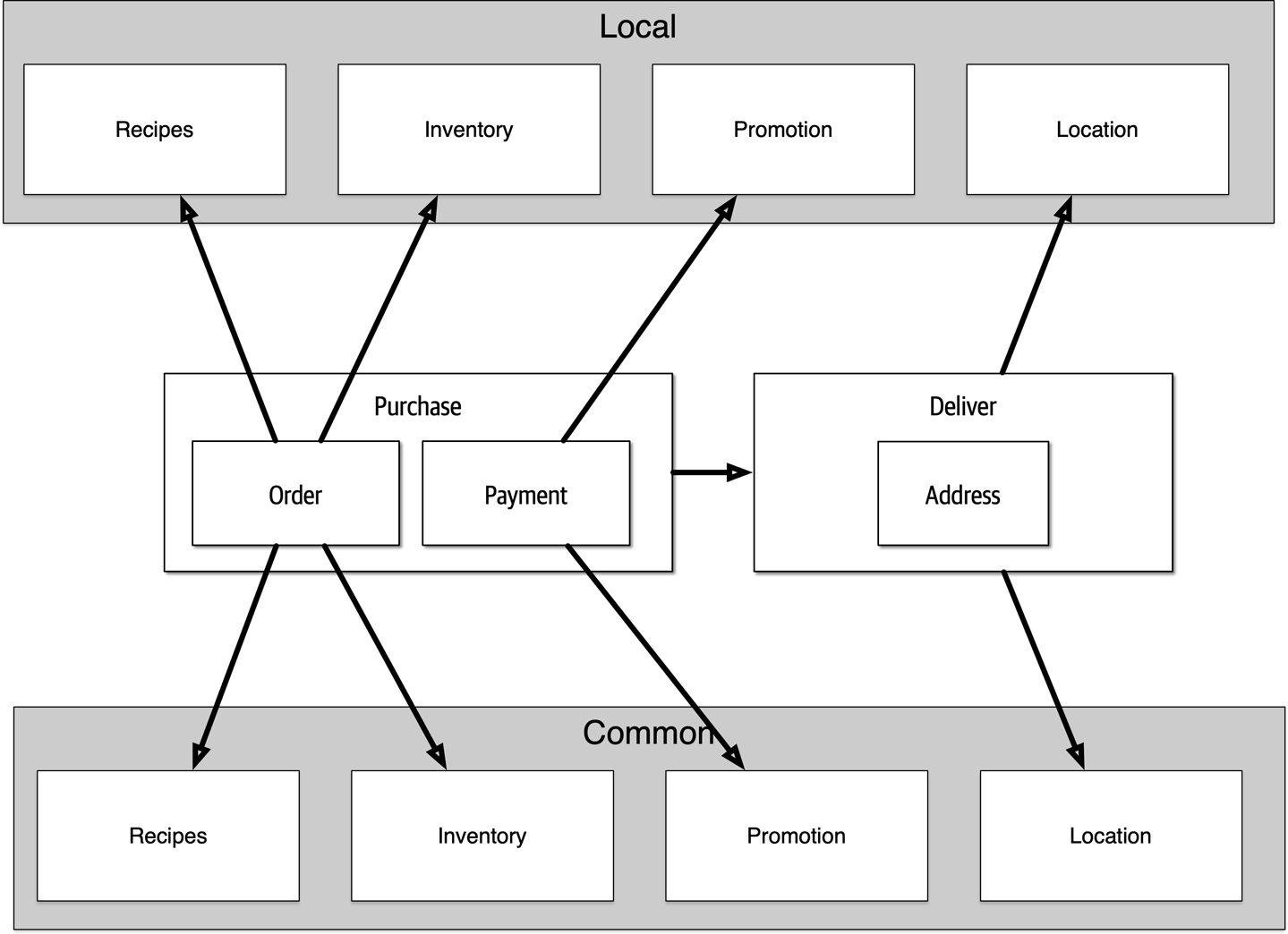

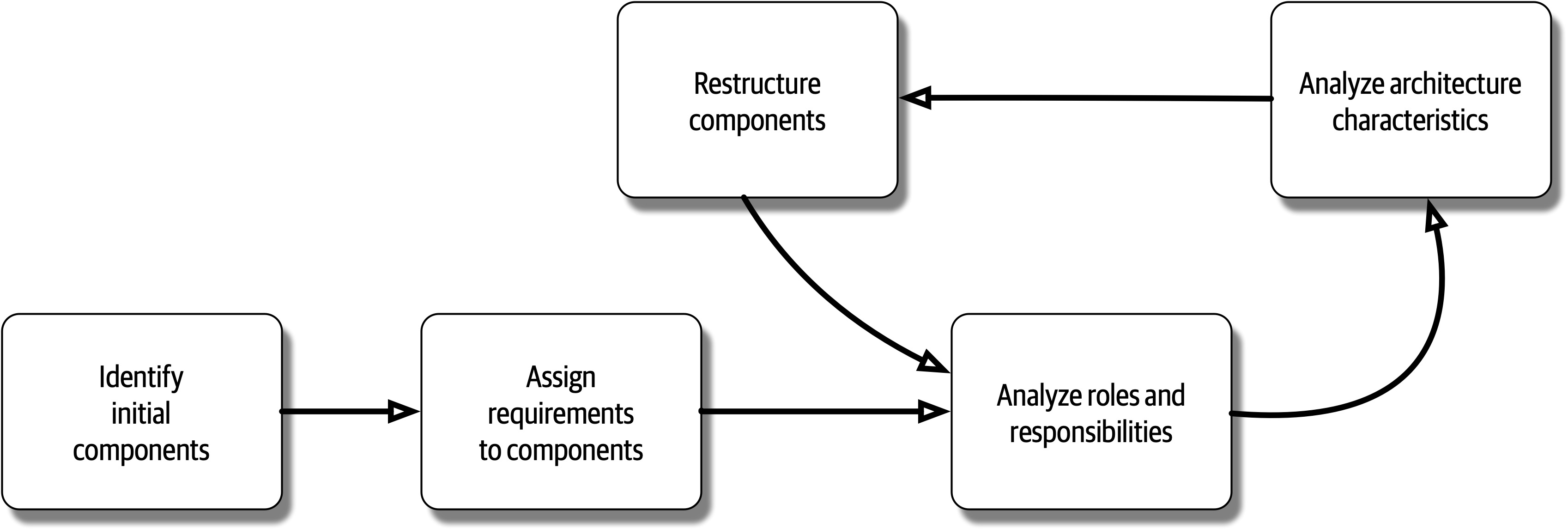

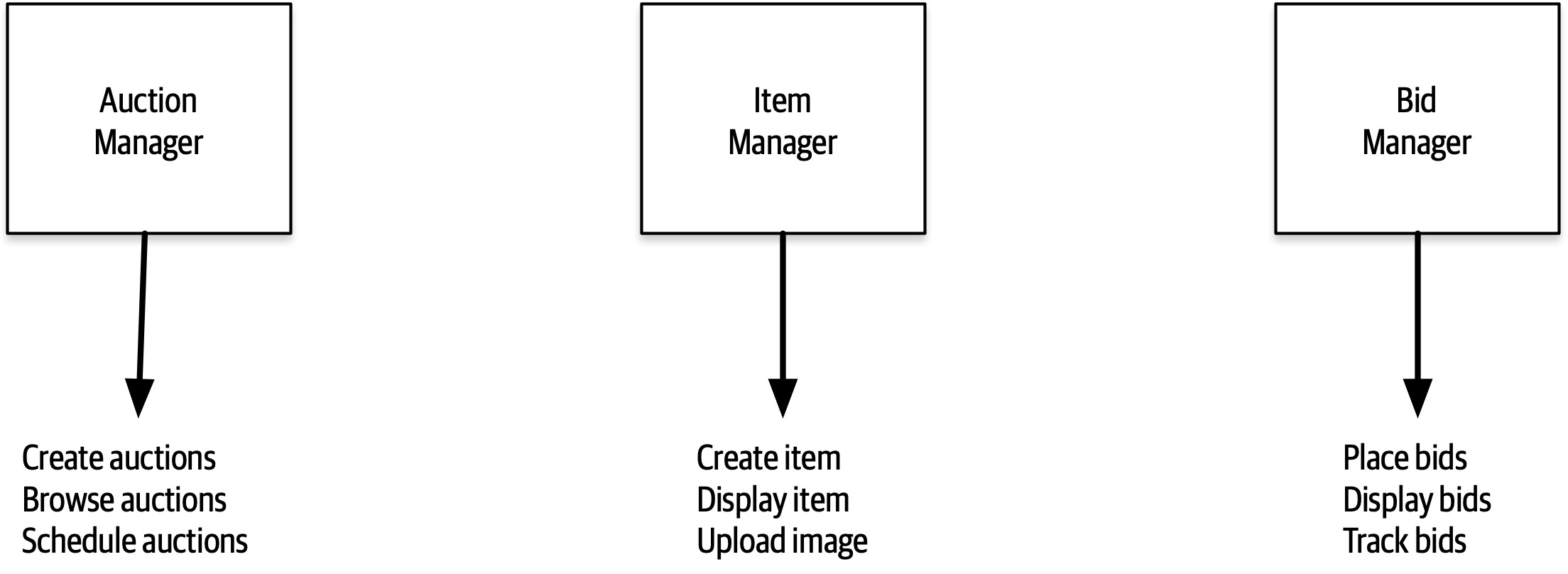

- 8. Component-Based Thinking

- II. Architecture Styles

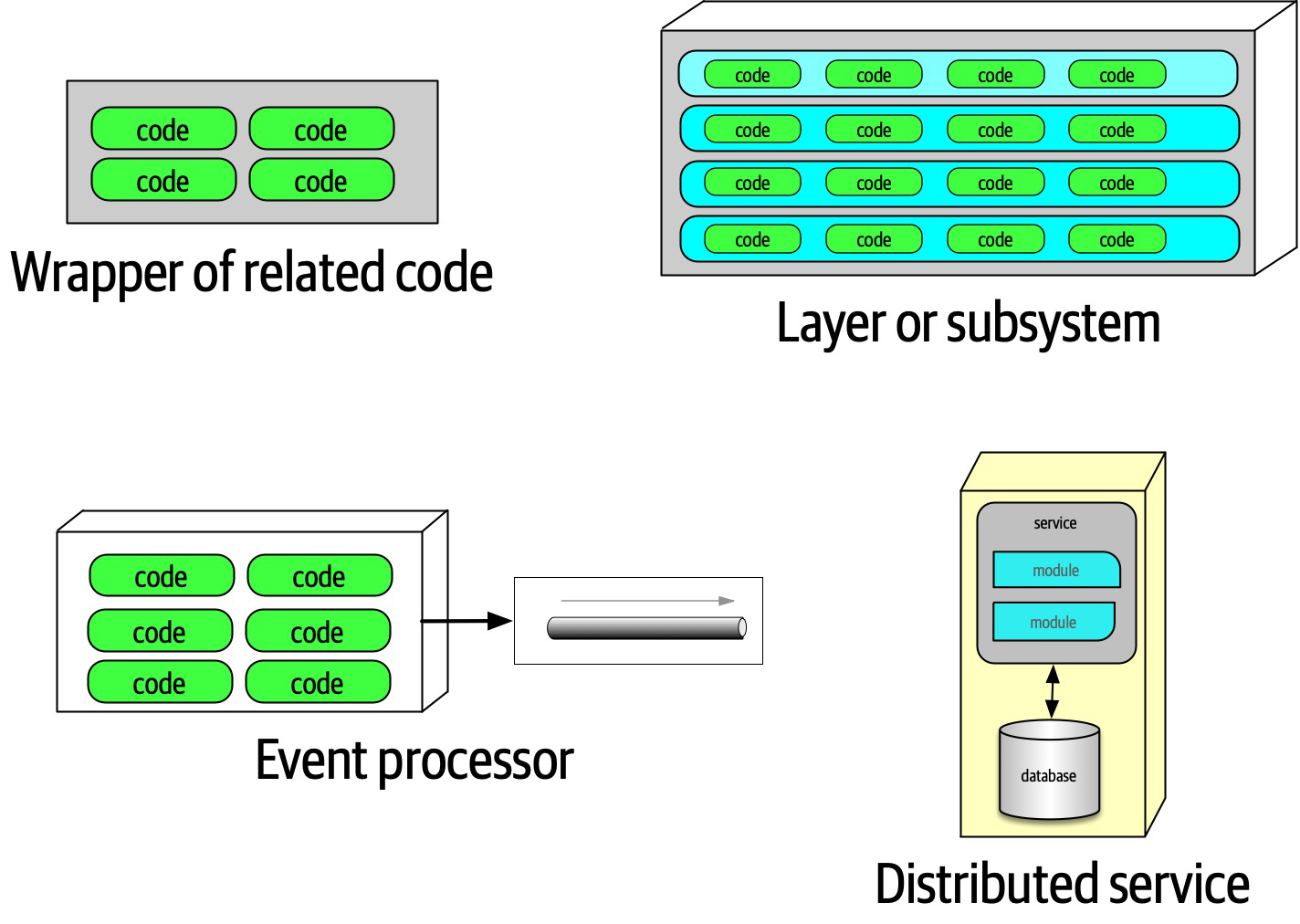

- 9. Foundations

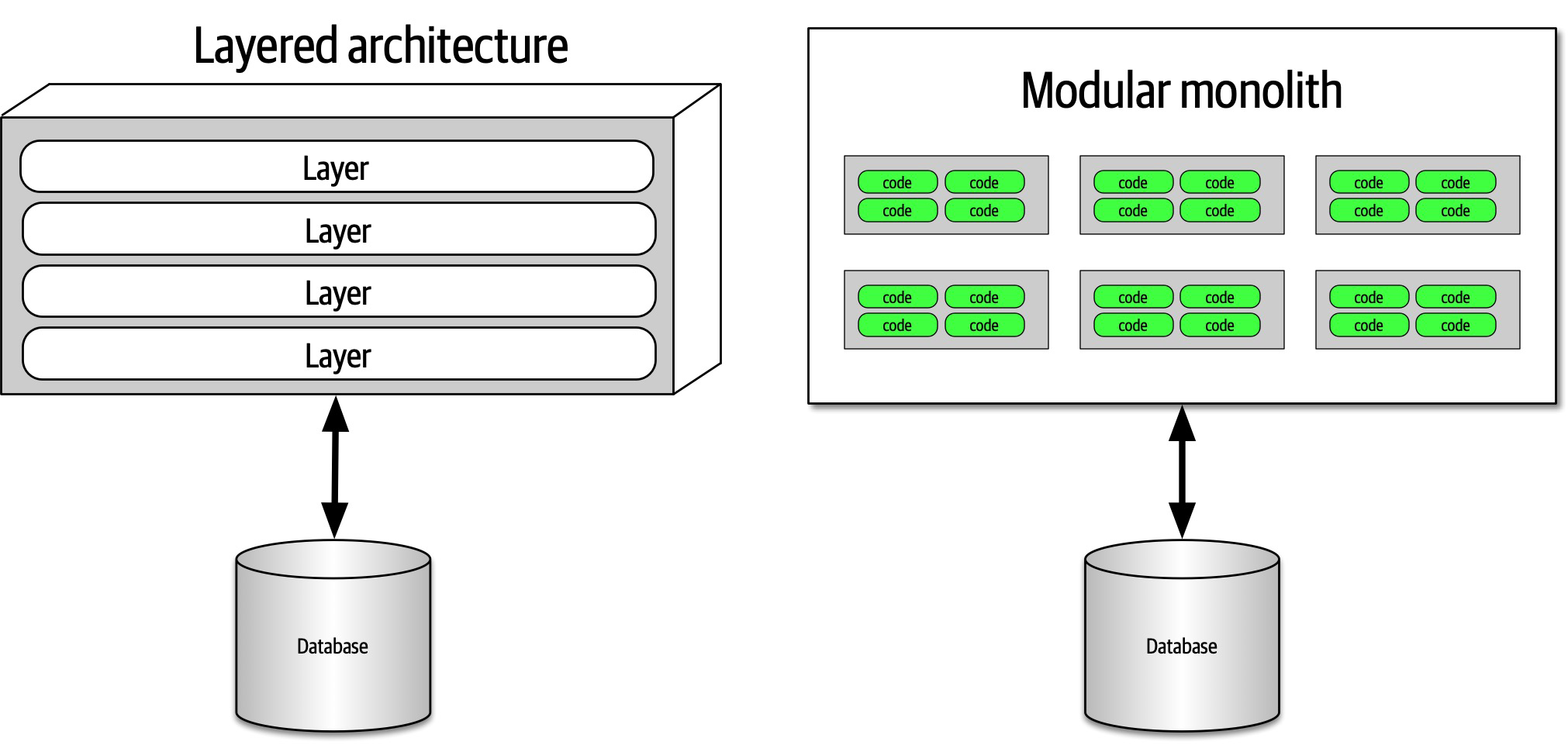

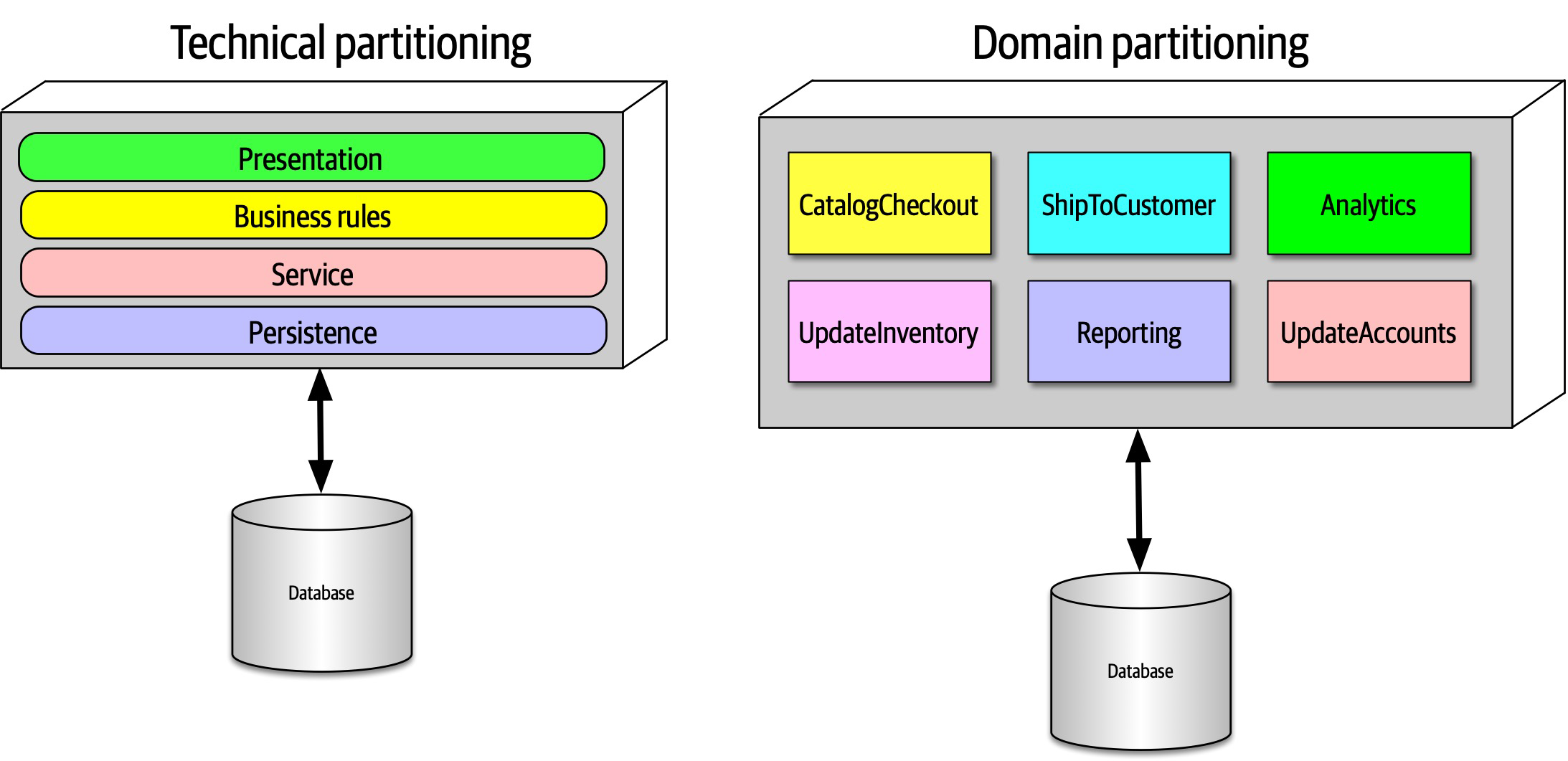

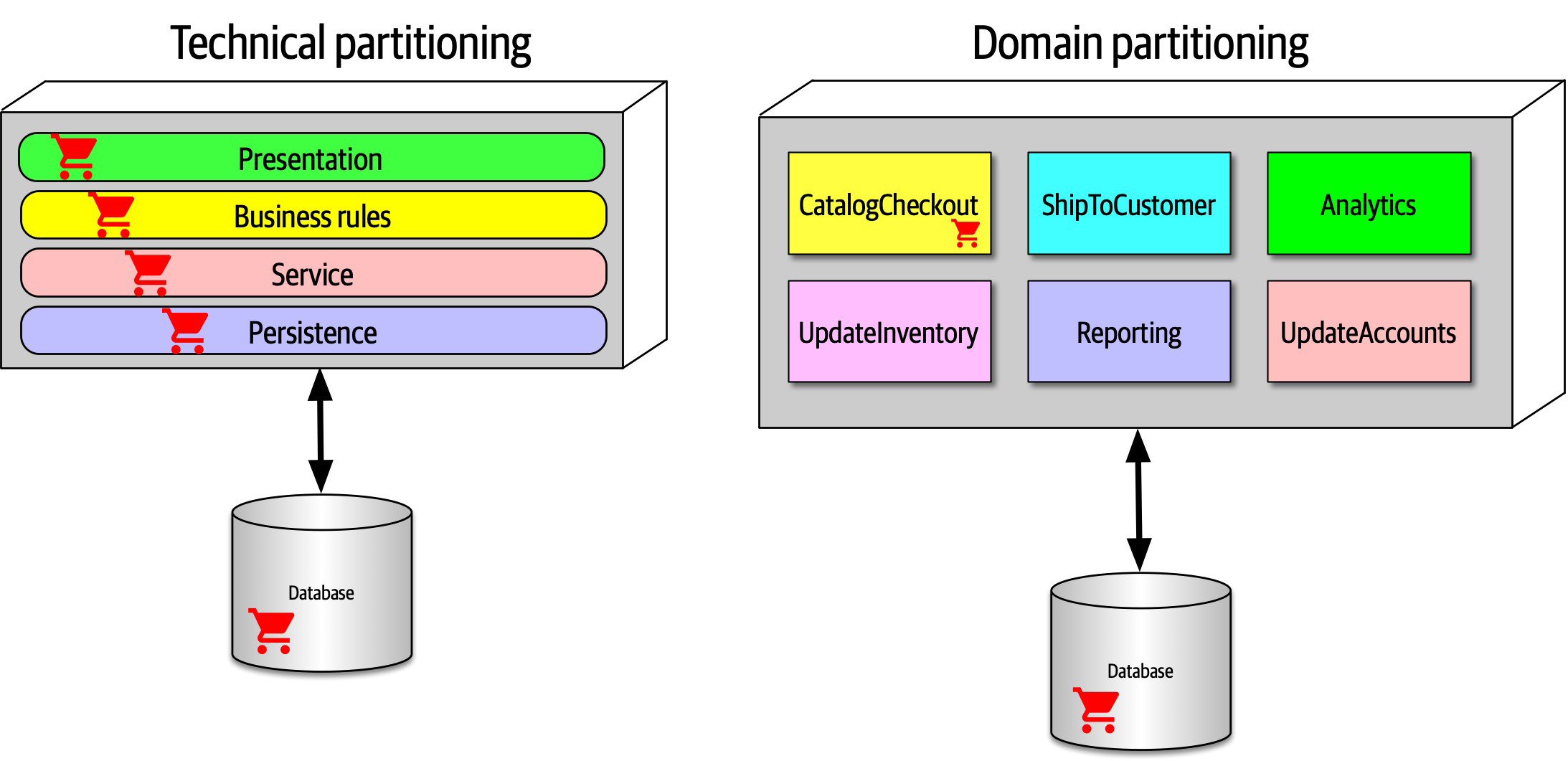

- Fundamental Patterns

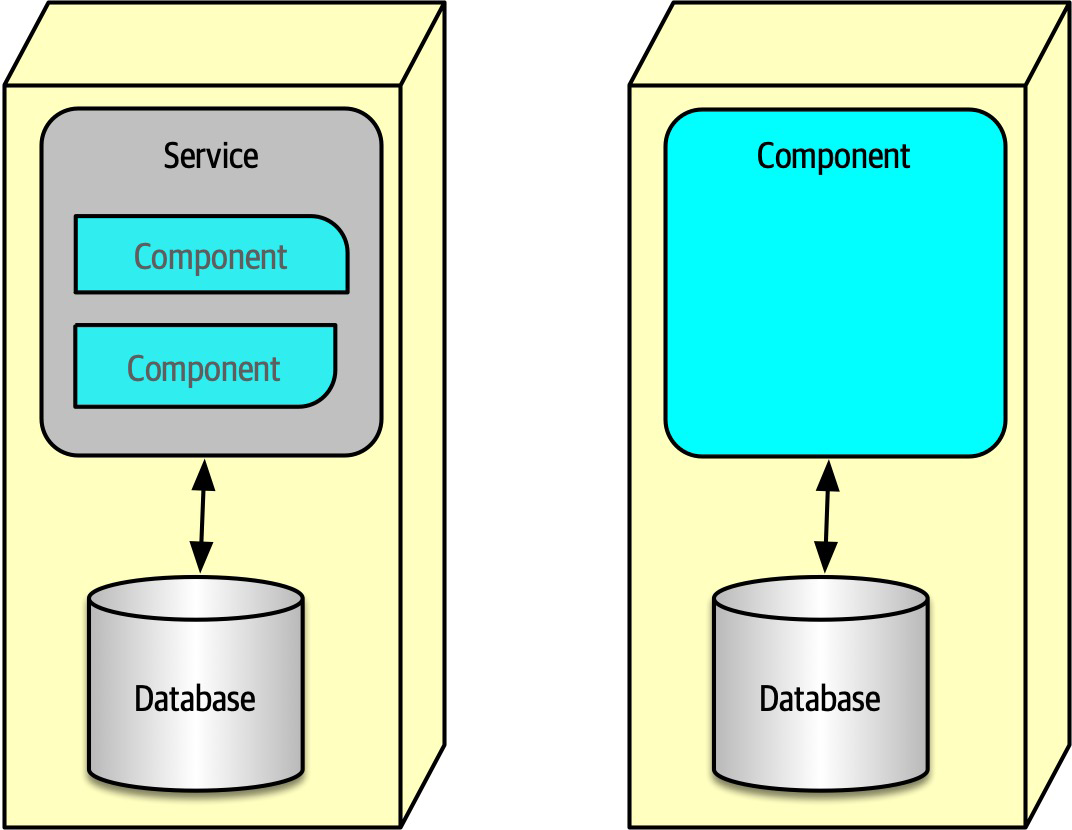

- Monolithic Versus Distributed Architectures

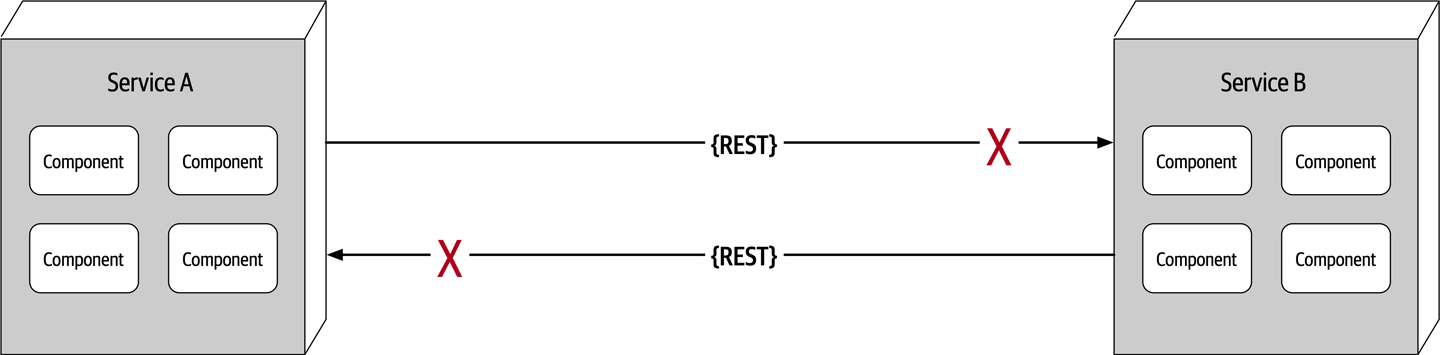

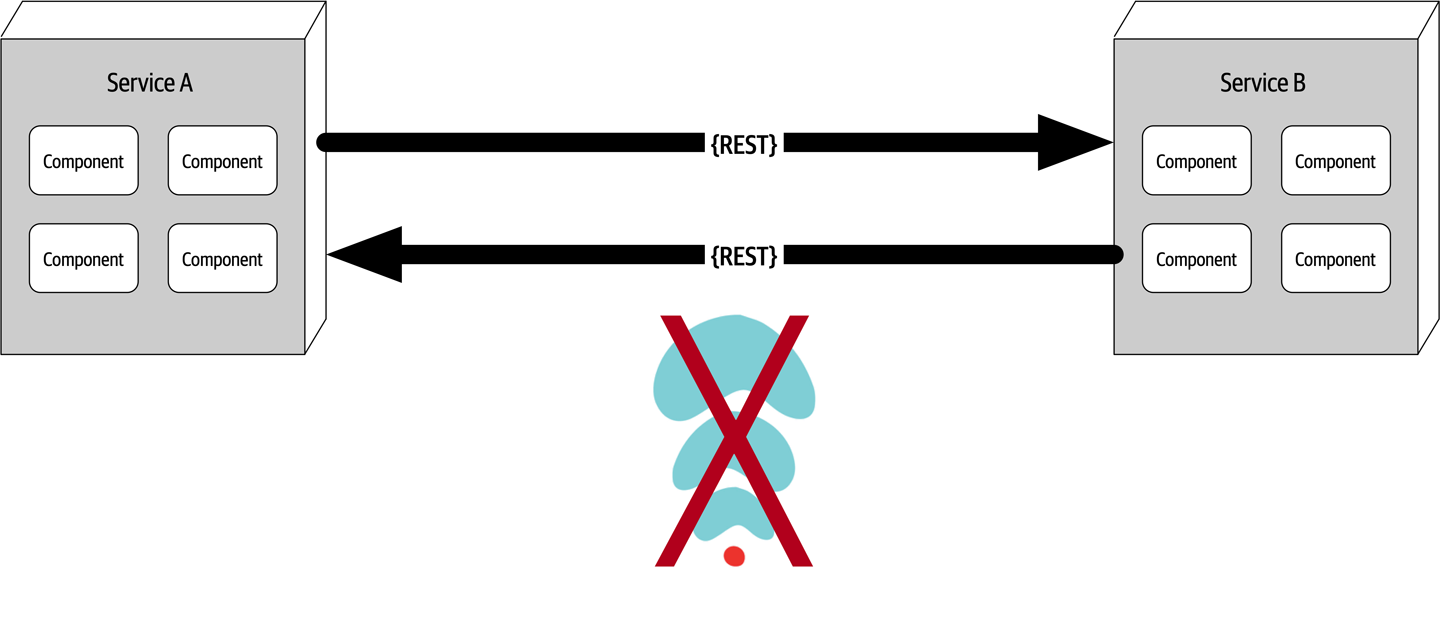

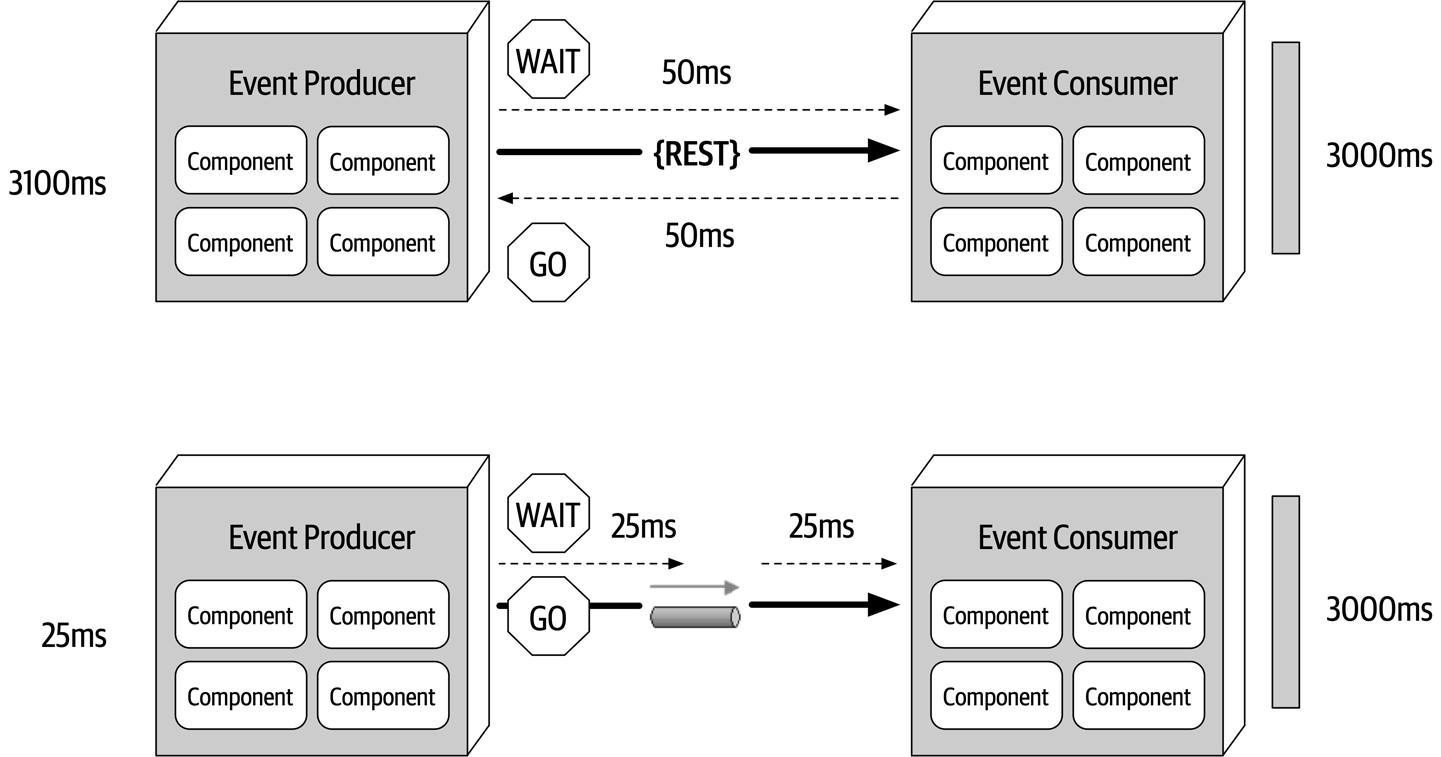

- Fallacy #1: The Network Is Reliable

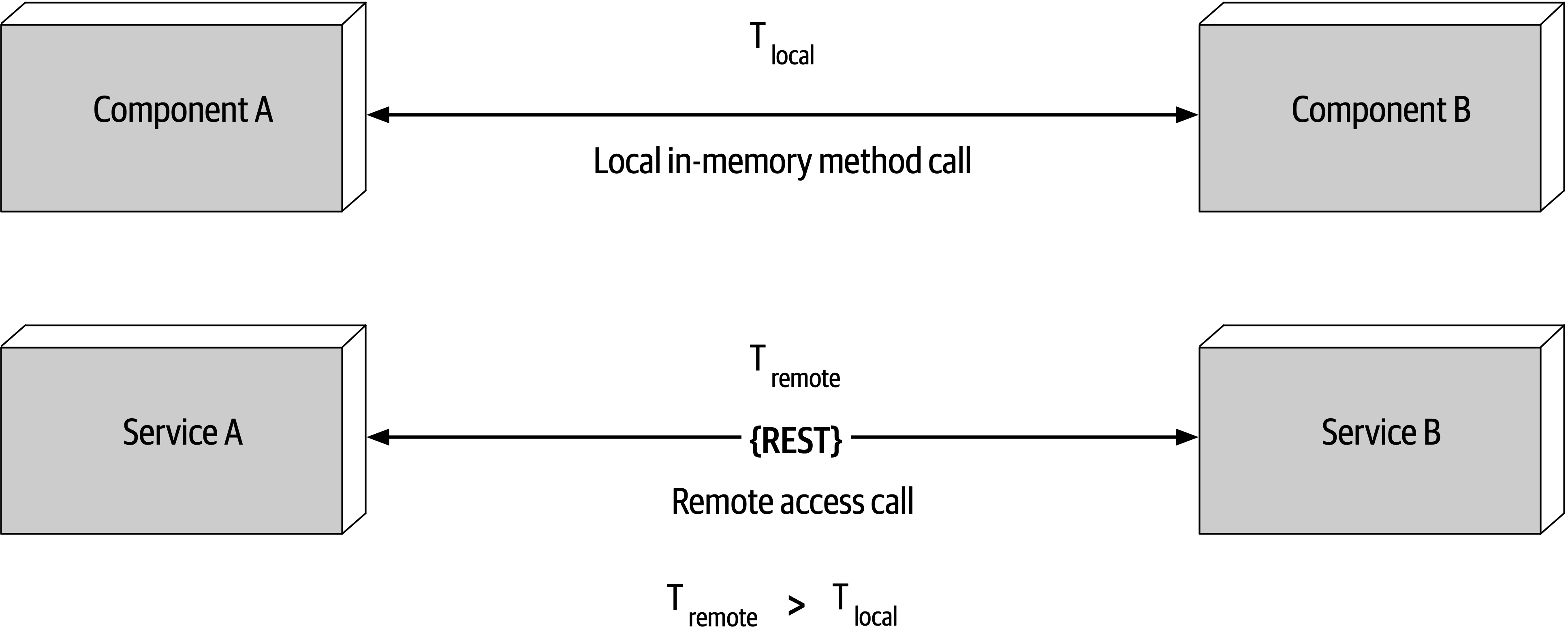

- Fallacy #2: Latency Is Zero

- Fallacy #3: Bandwidth Is Infinite

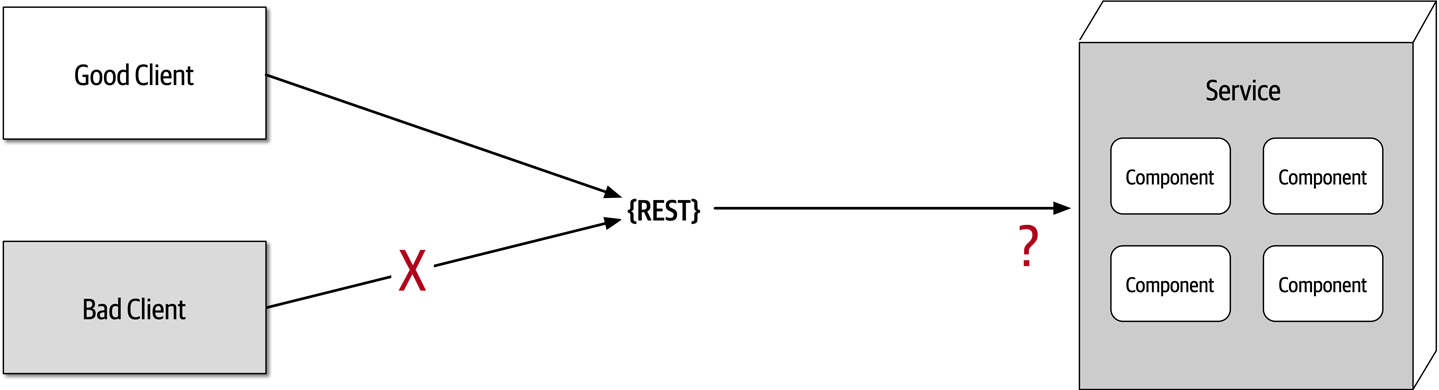

- Fallacy #4: The Network Is Secure

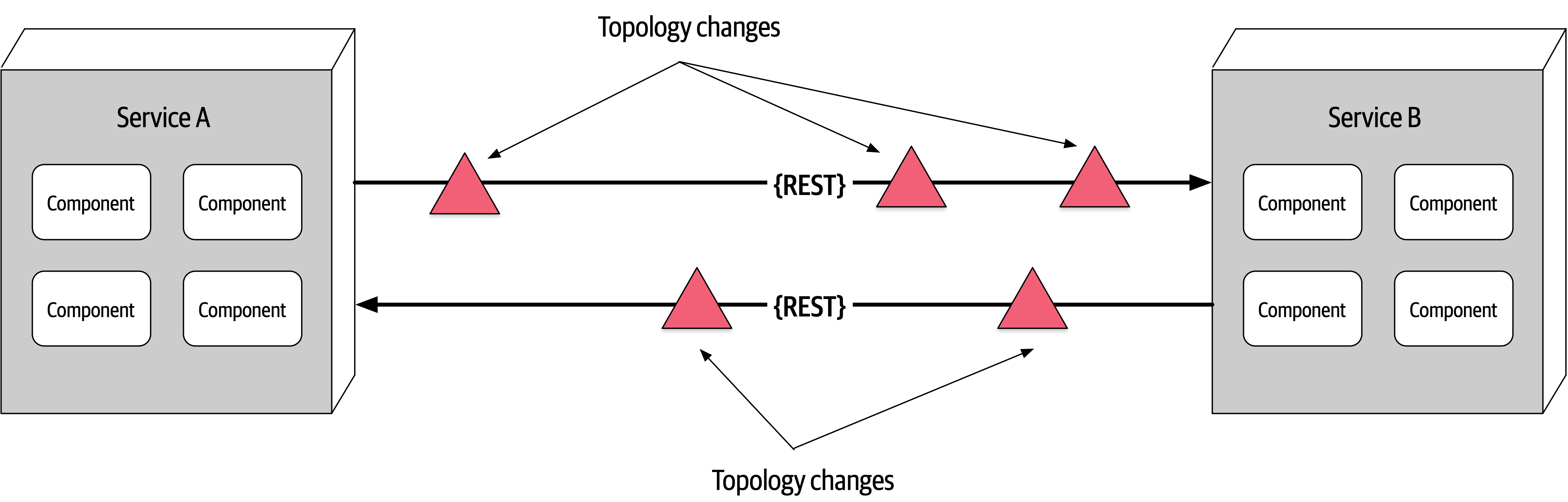

- Fallacy #5: The Topology Never Changes

- Fallacy #6: There Is Only One Administrator

- Fallacy #7: Transport Cost Is Zero

- Fallacy #8: The Network Is Homogeneous

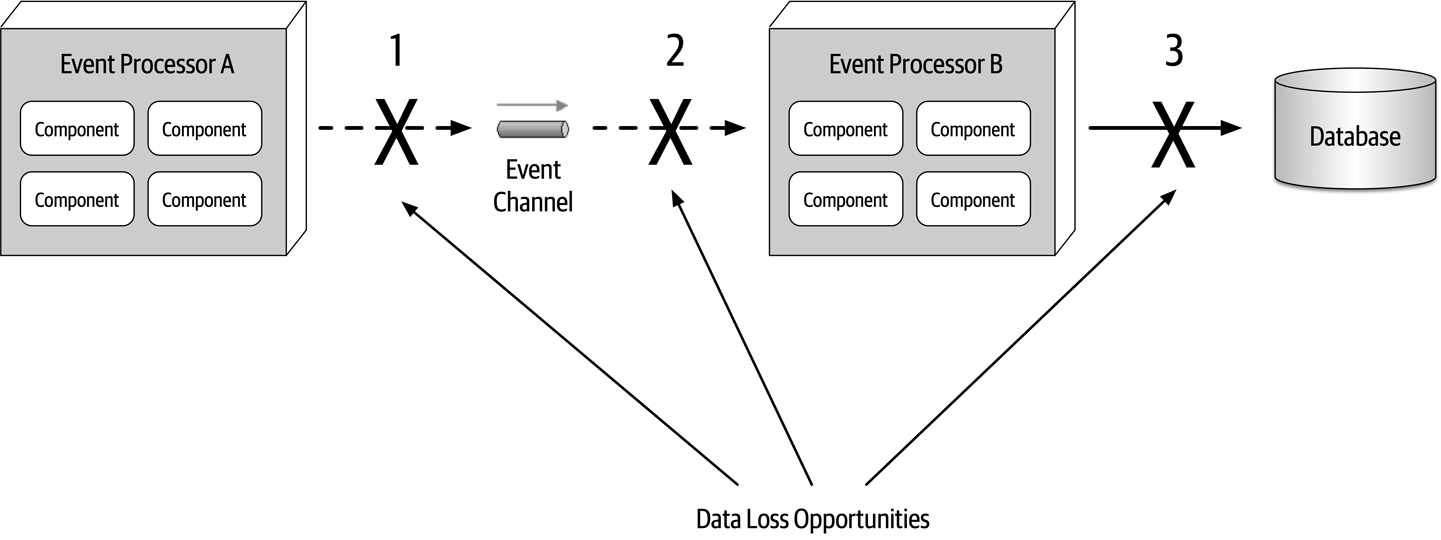

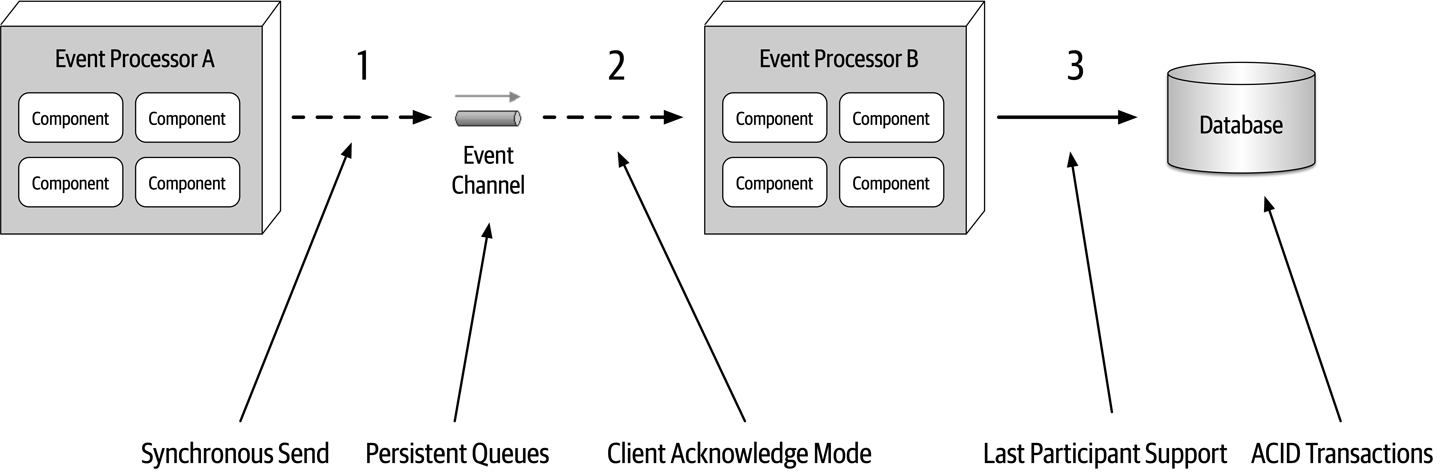

- Other Distributed Considerations

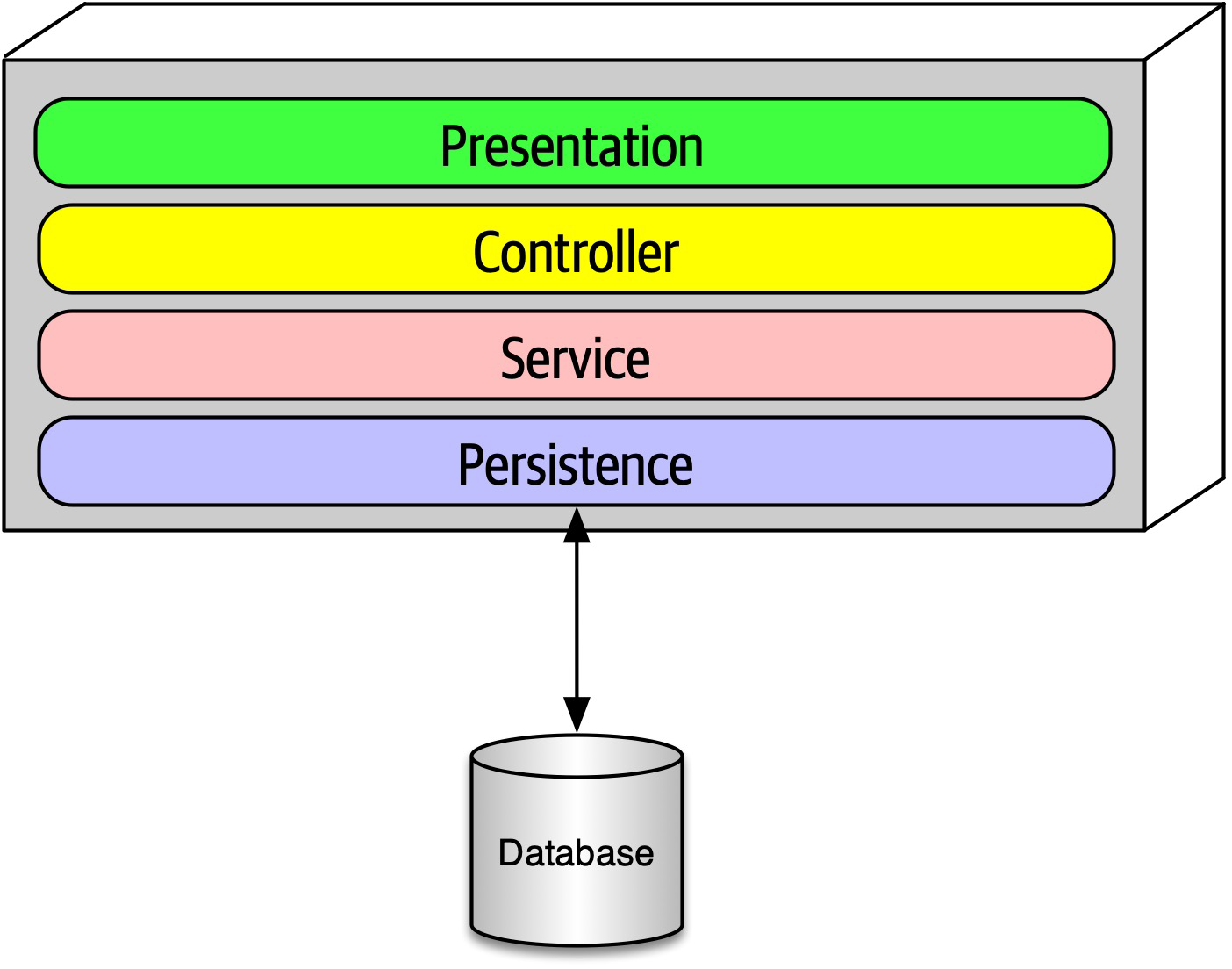

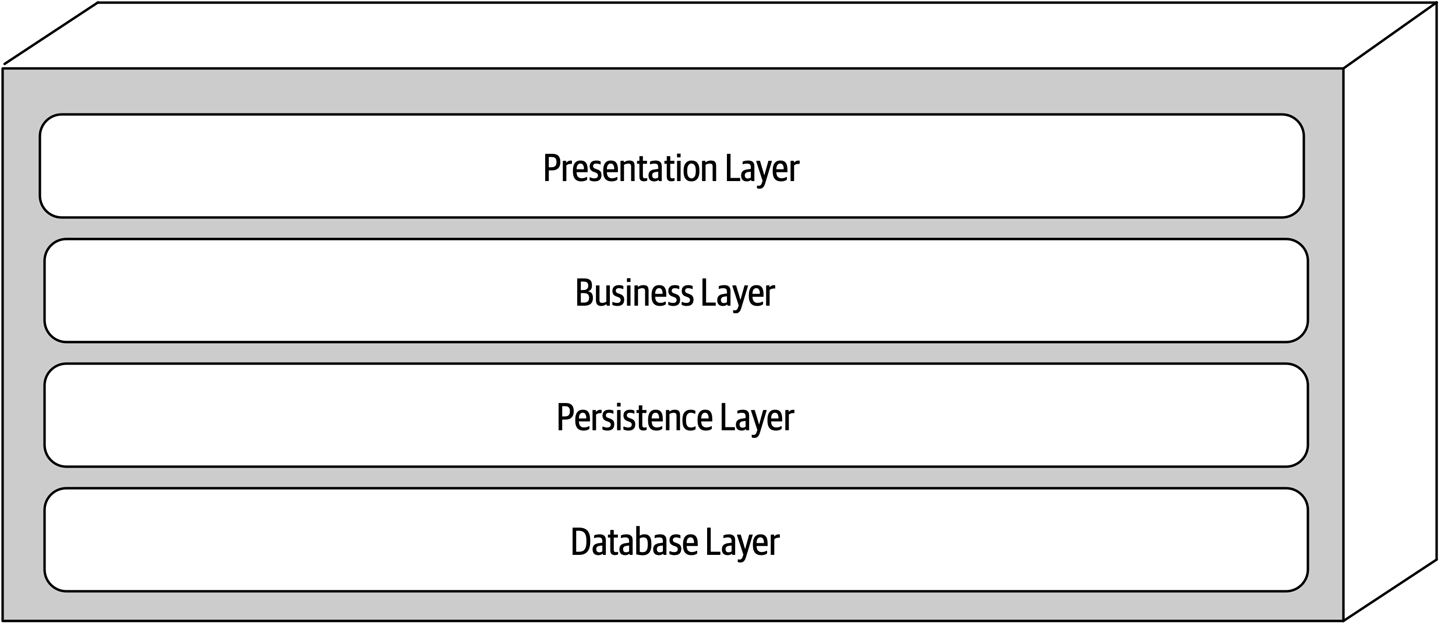

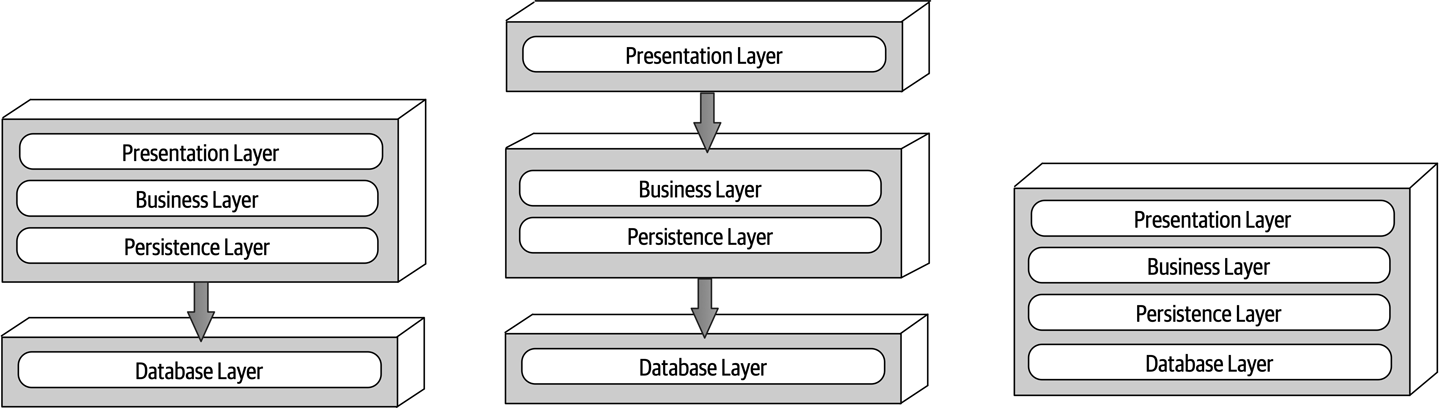

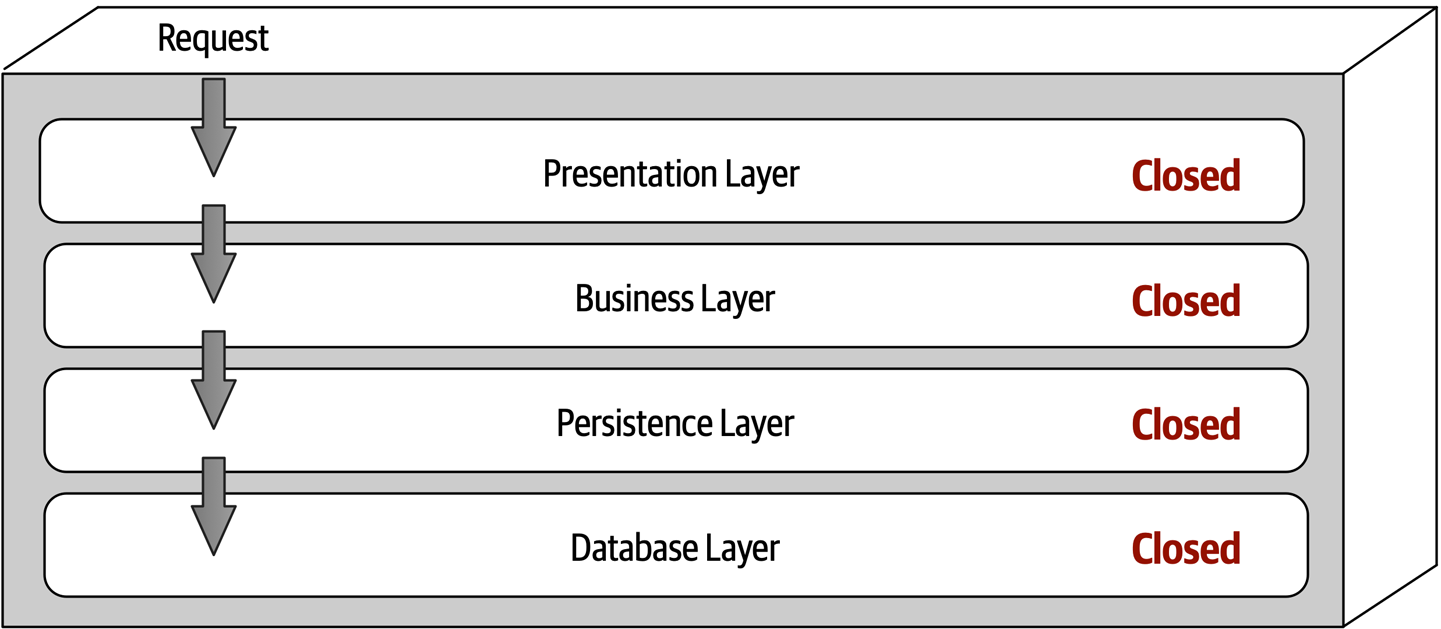

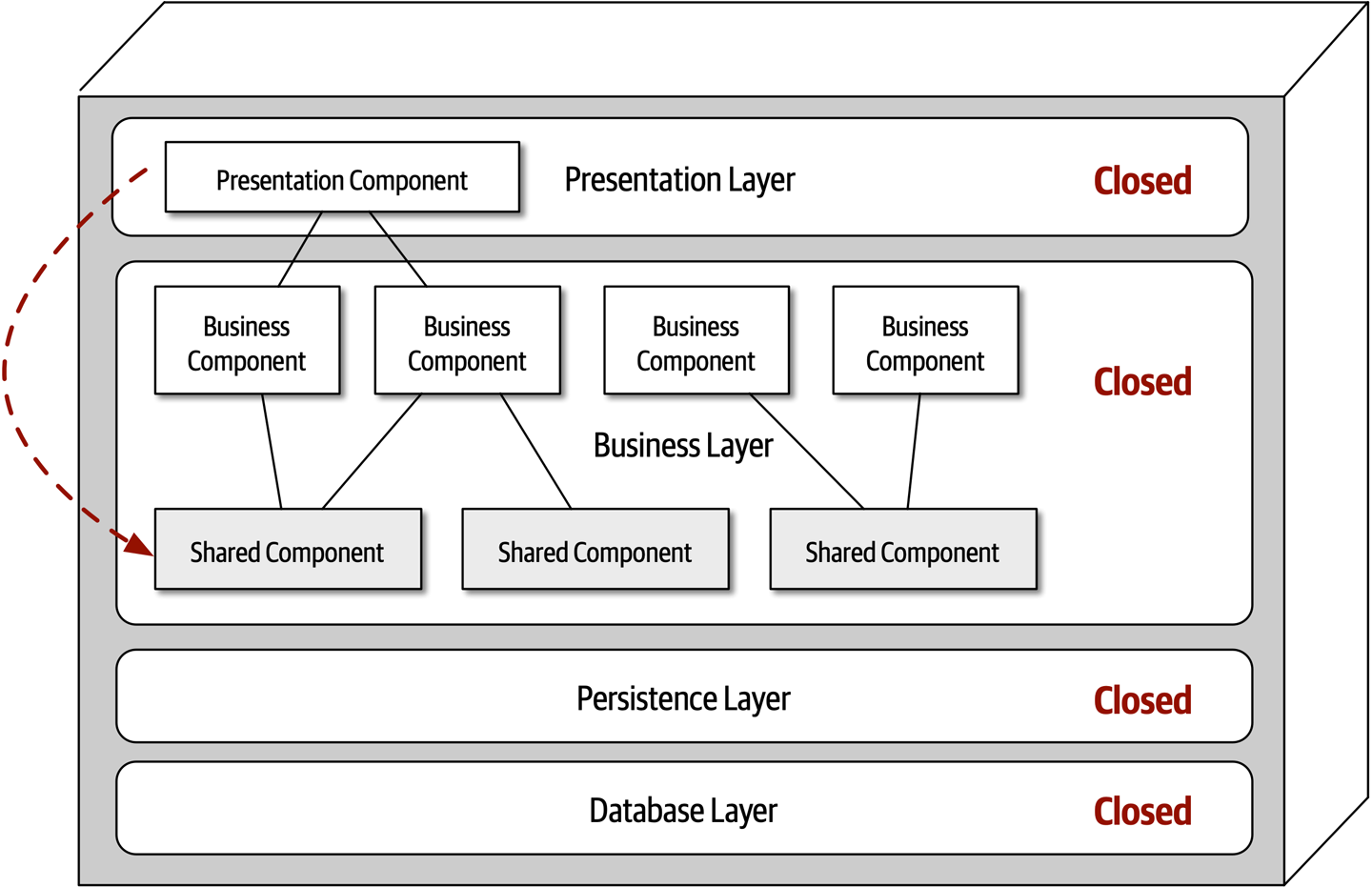

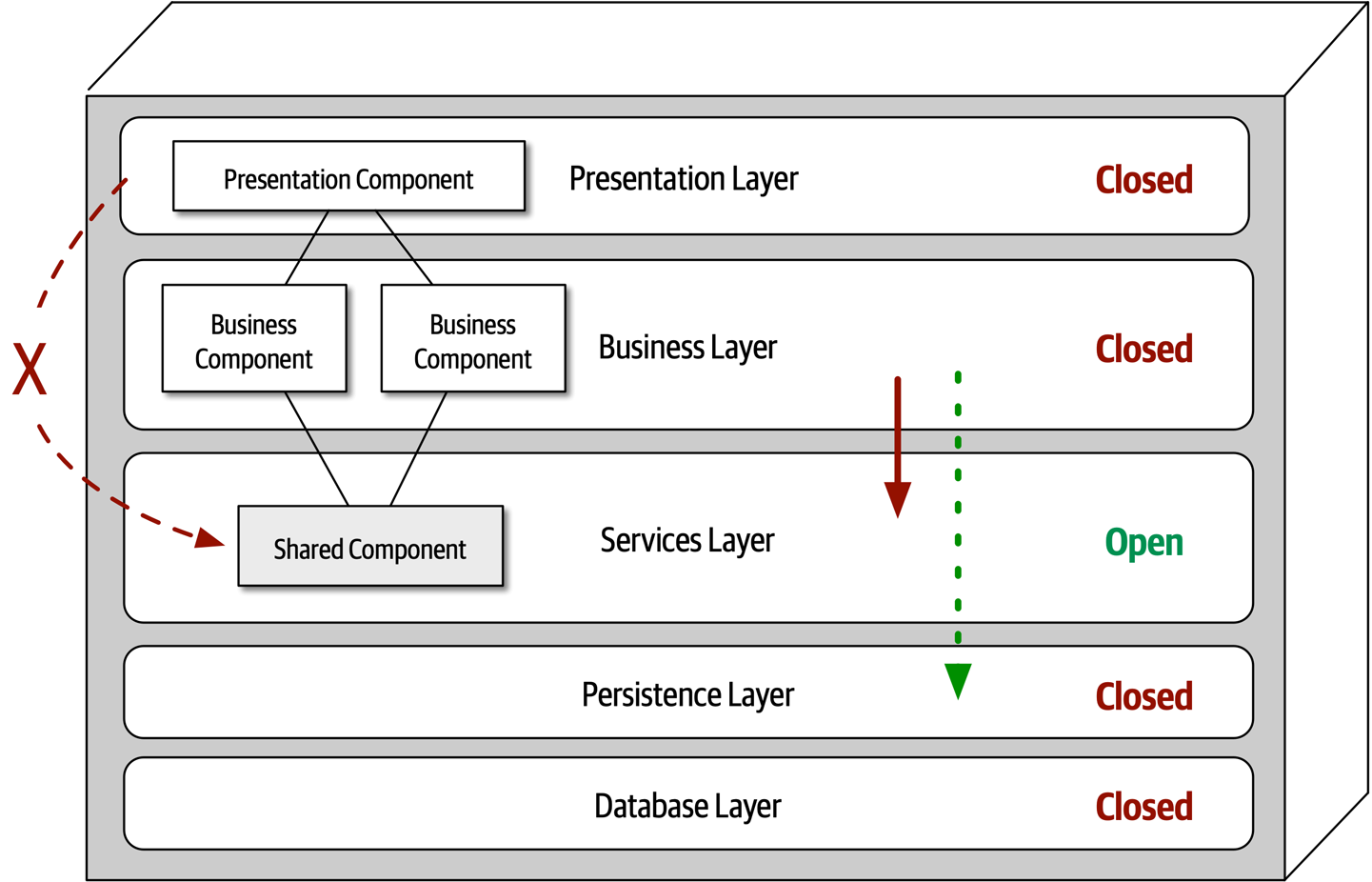

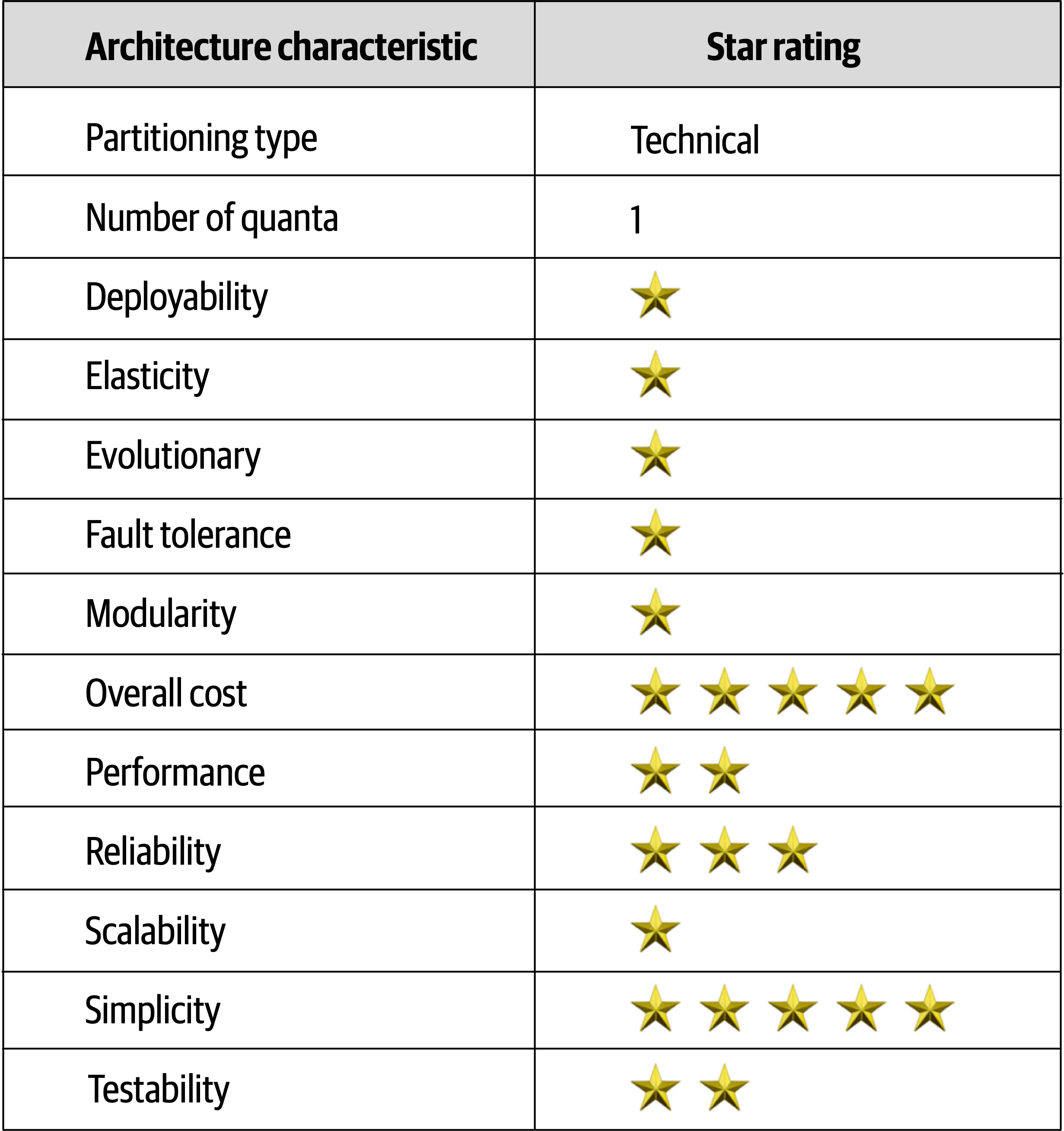

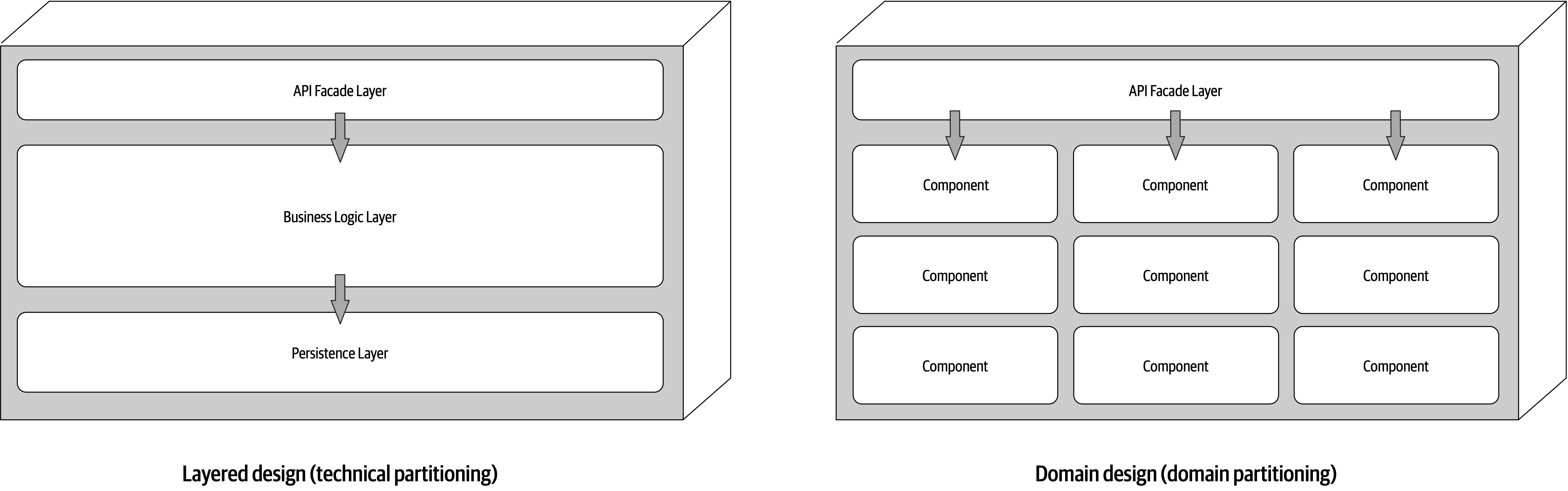

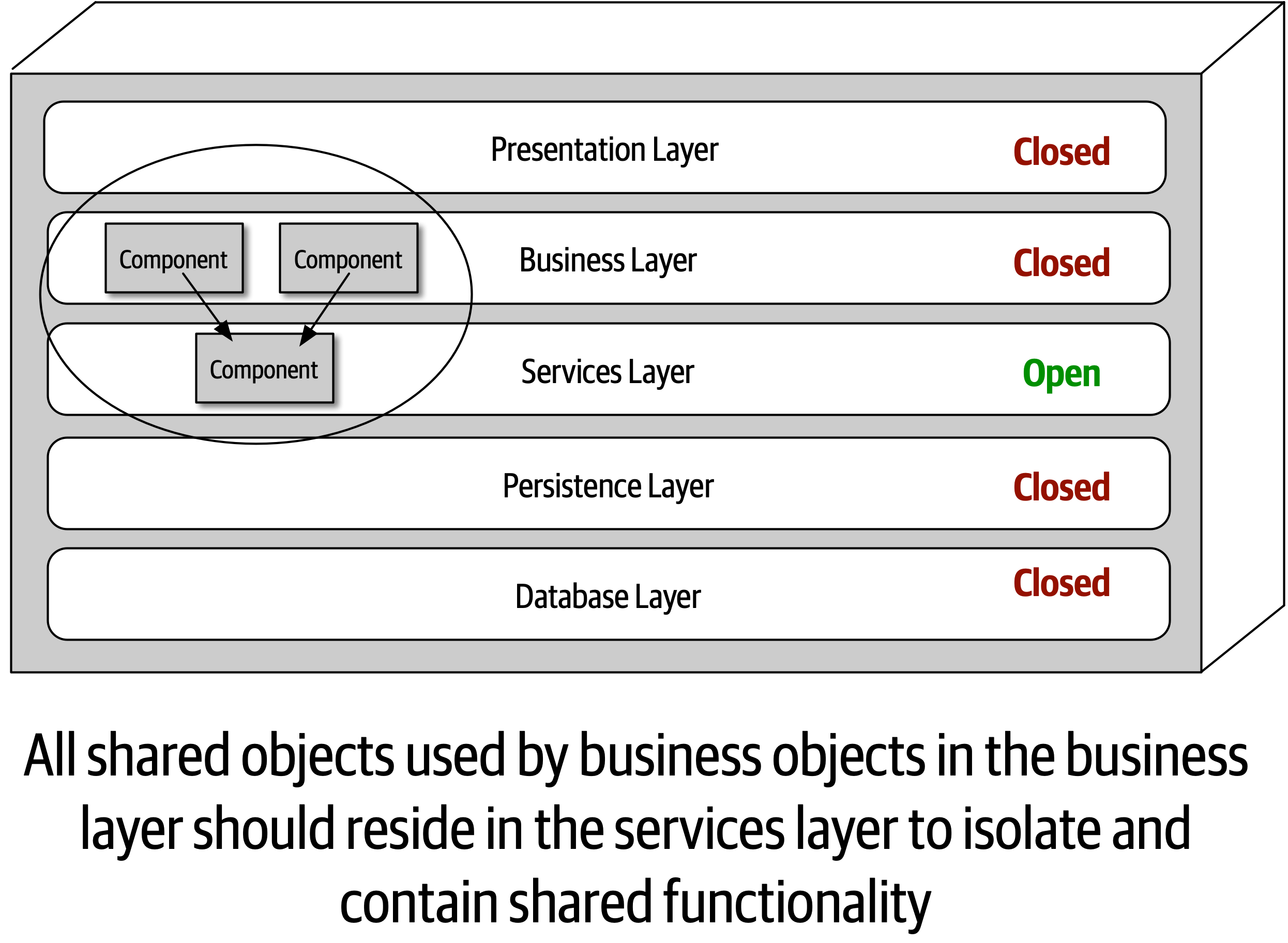

- 10. Layered Architecture Style

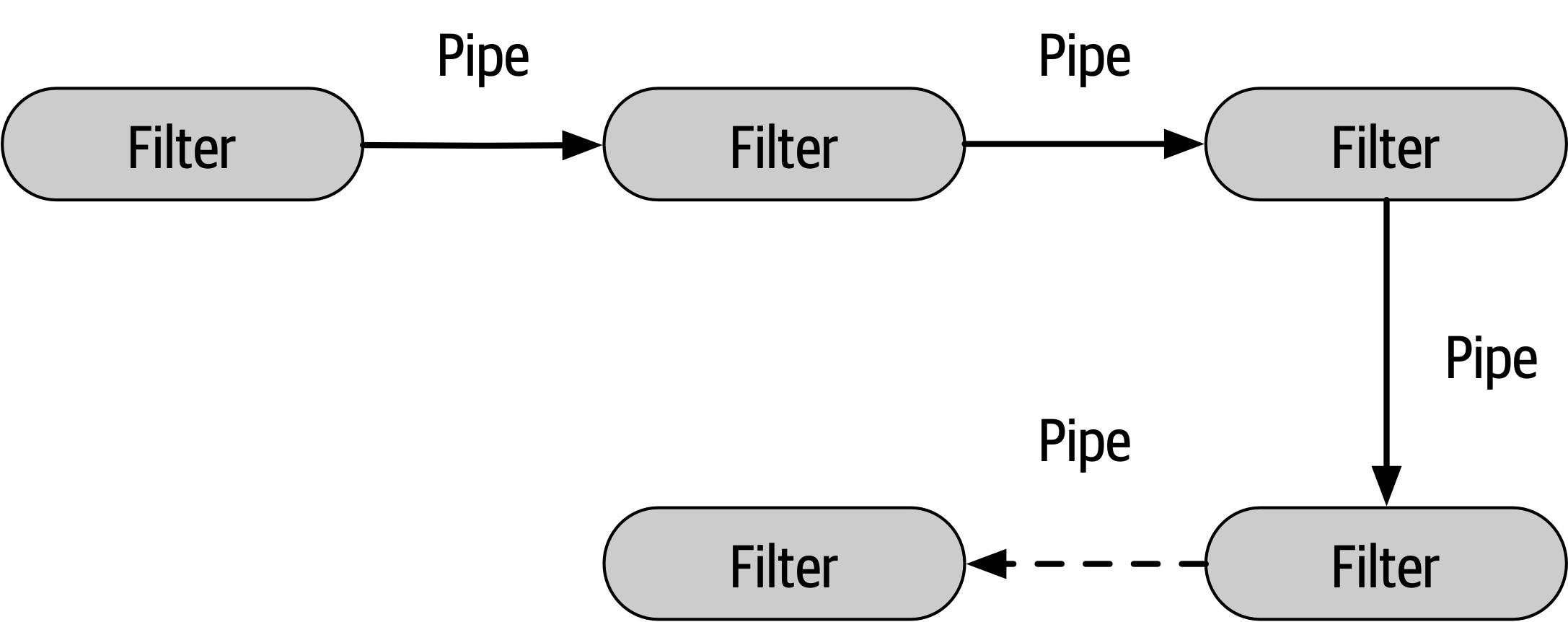

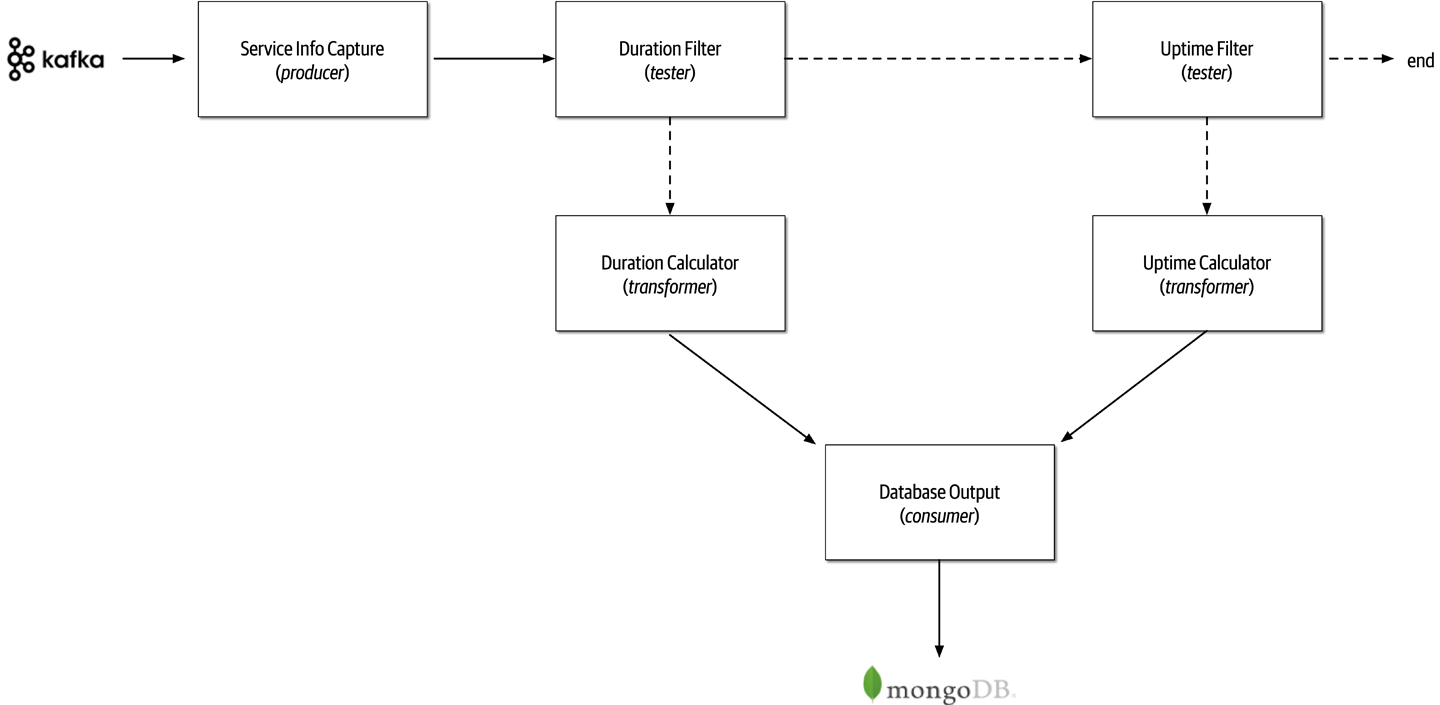

- 11. Pipeline Architecture Style

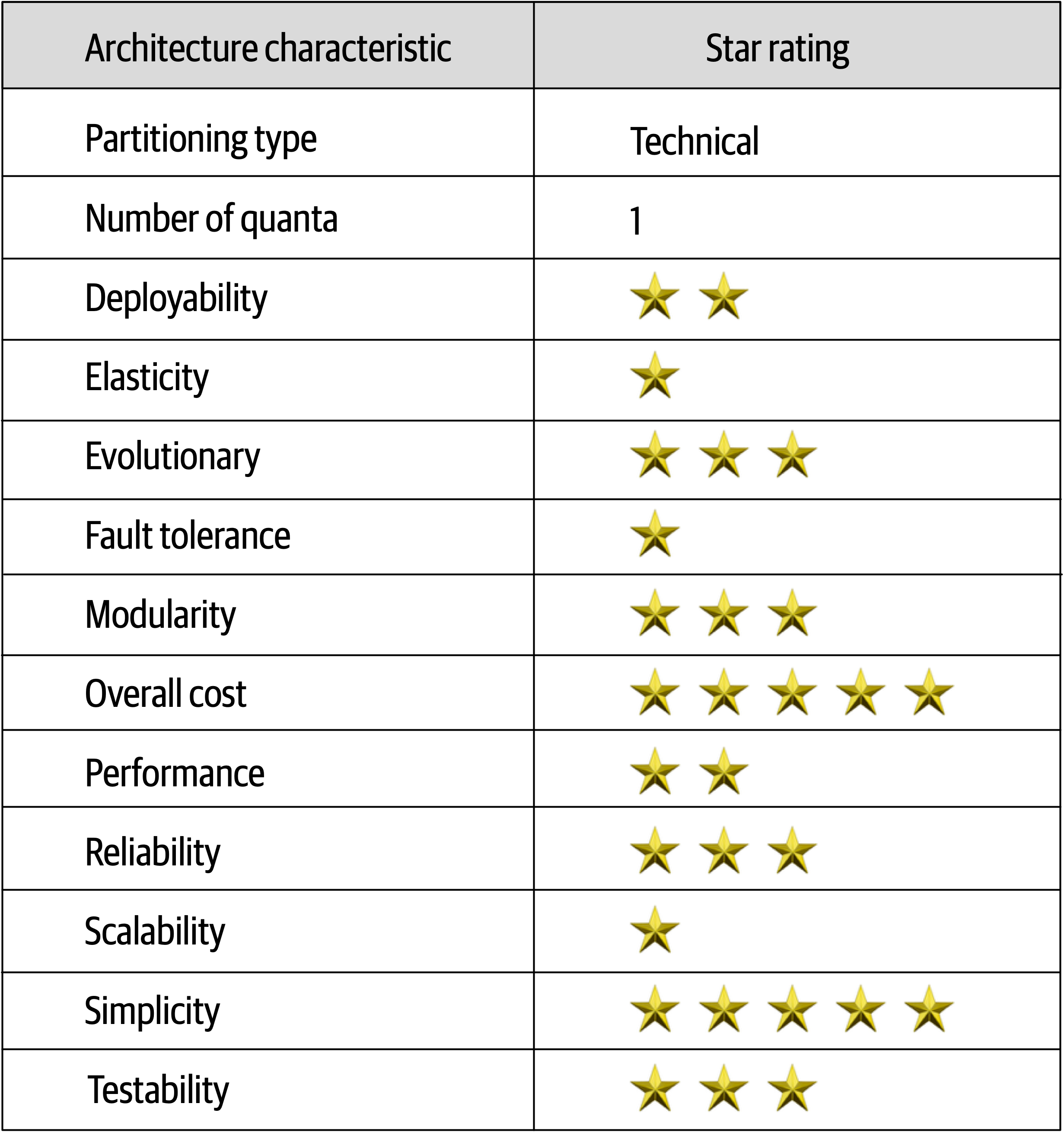

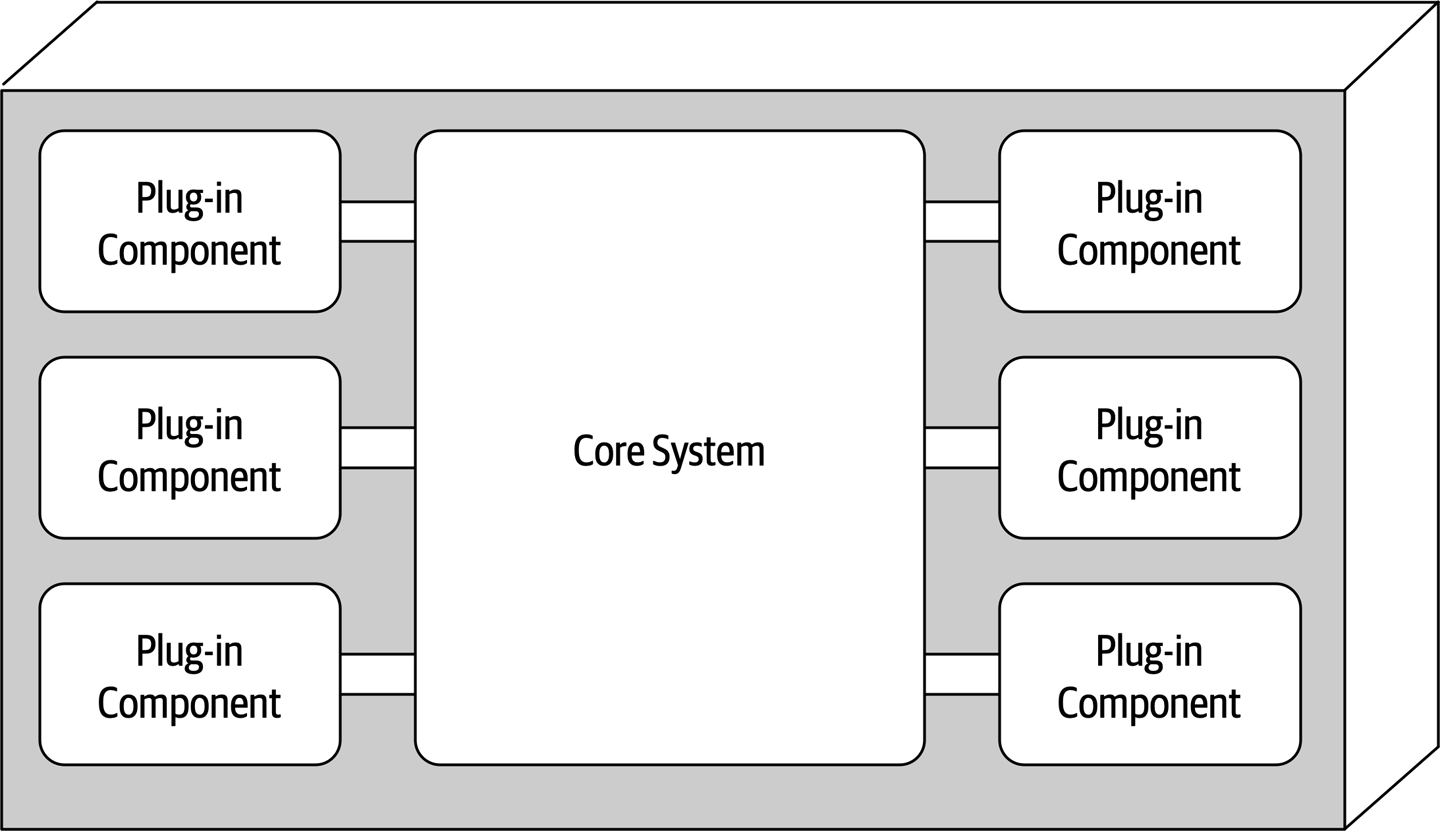

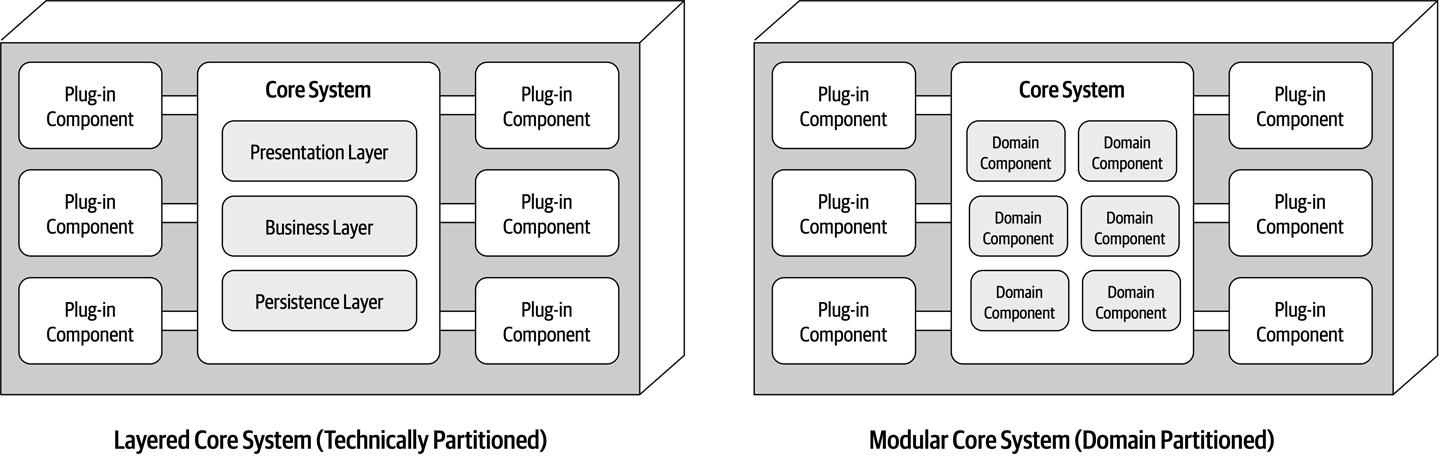

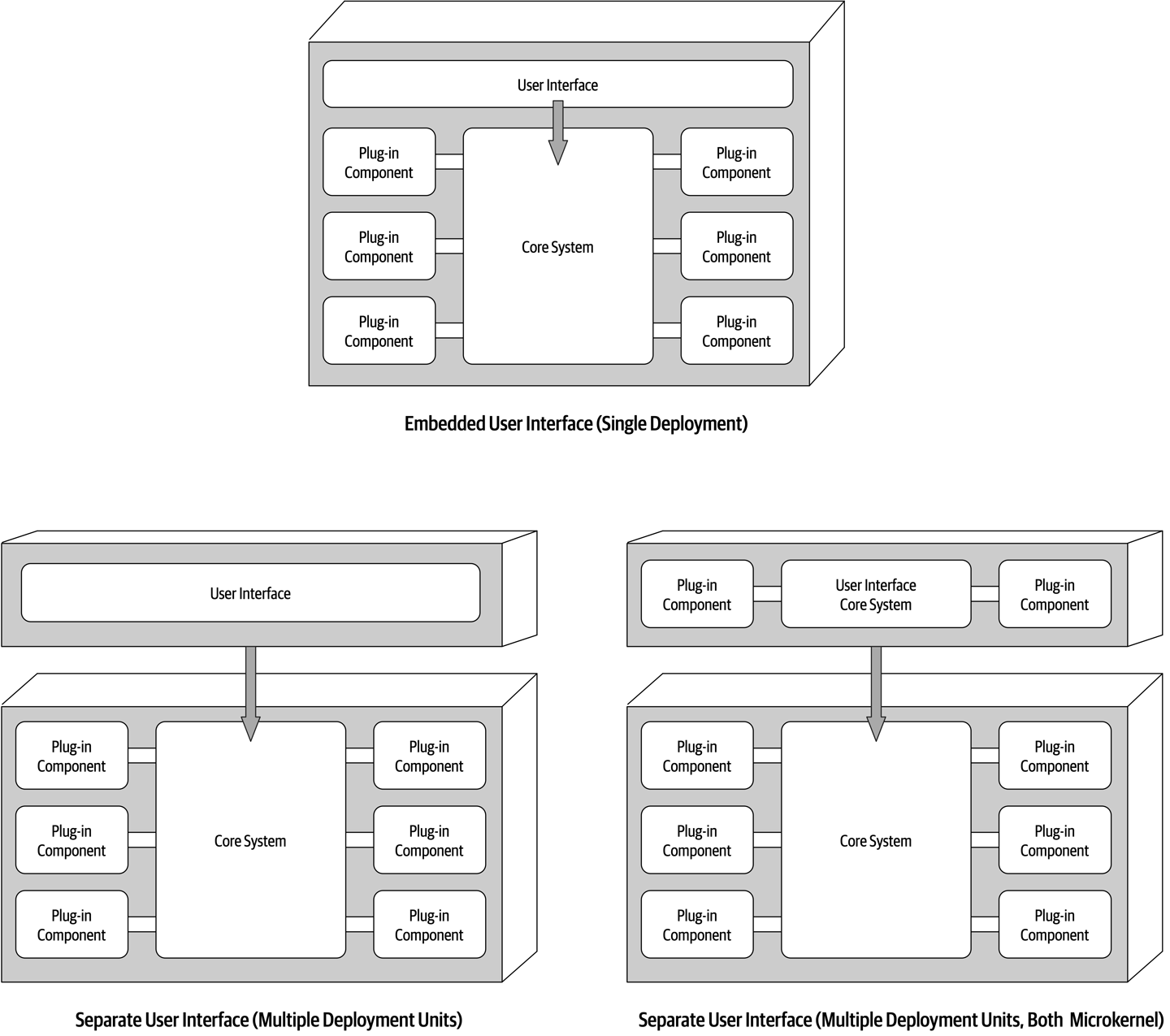

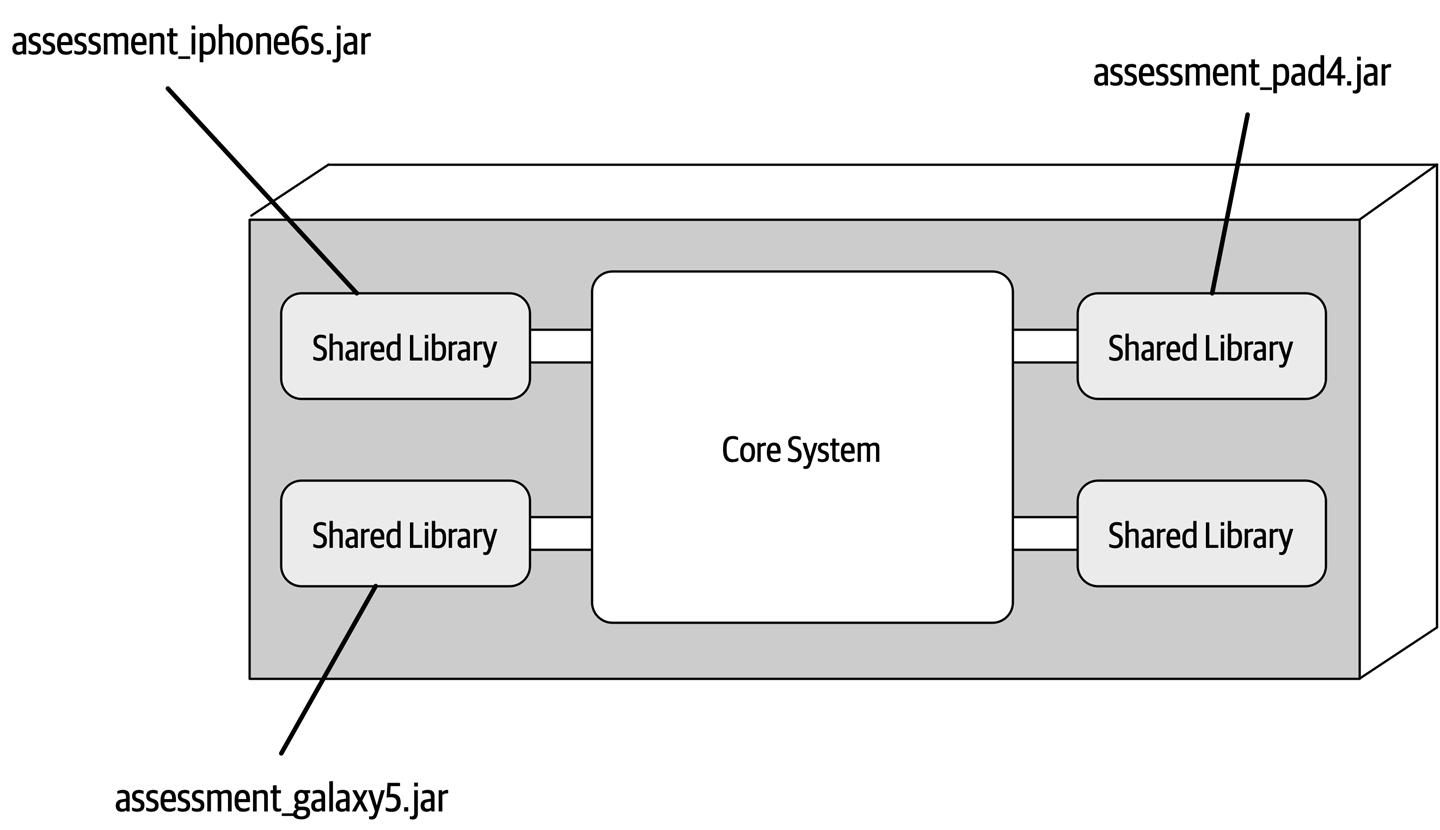

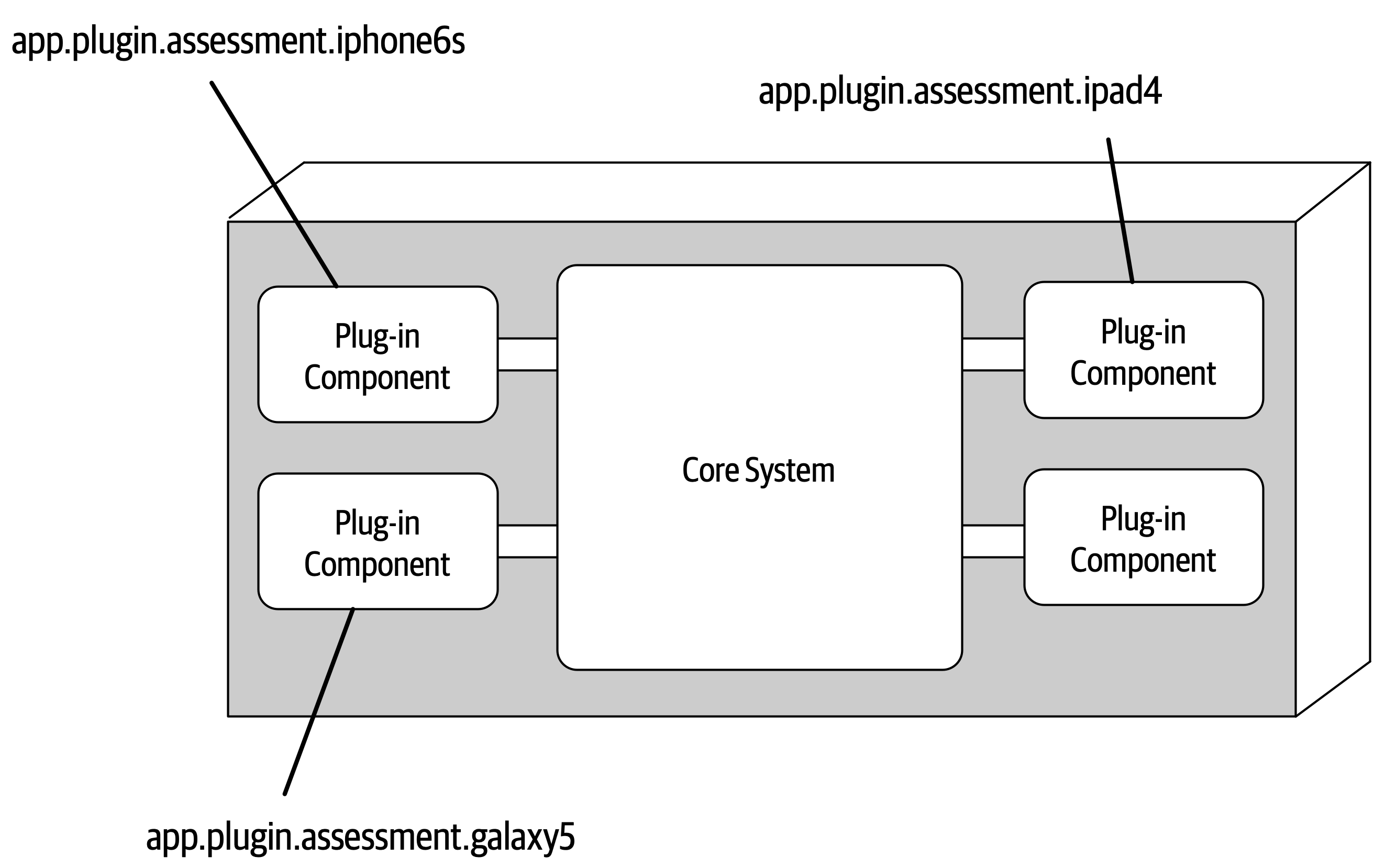

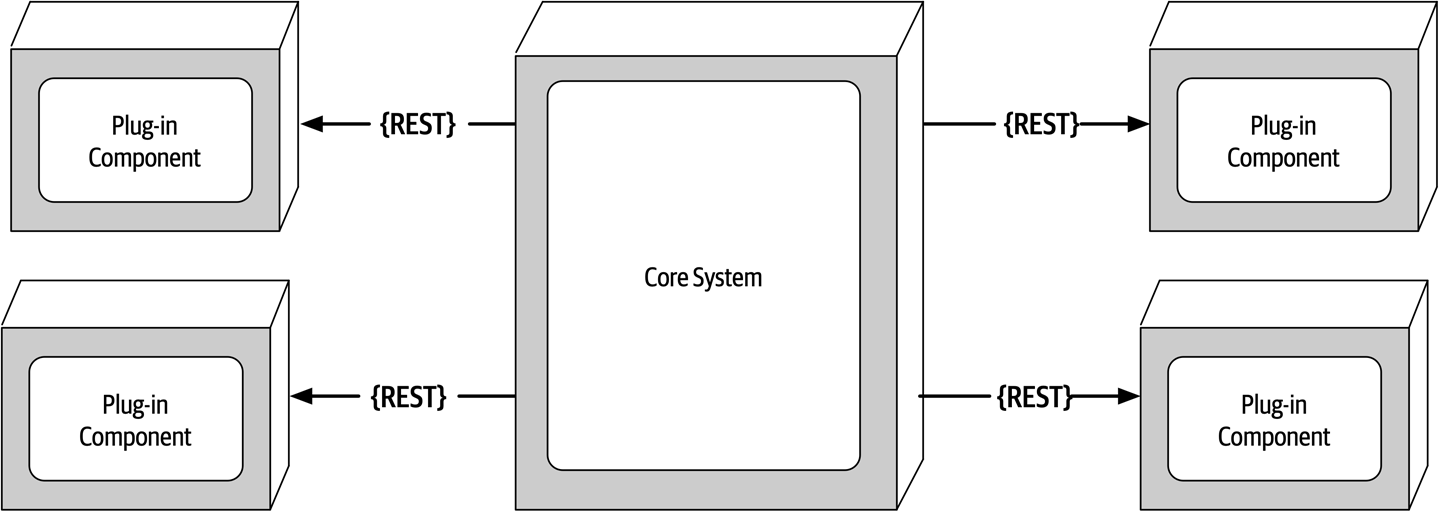

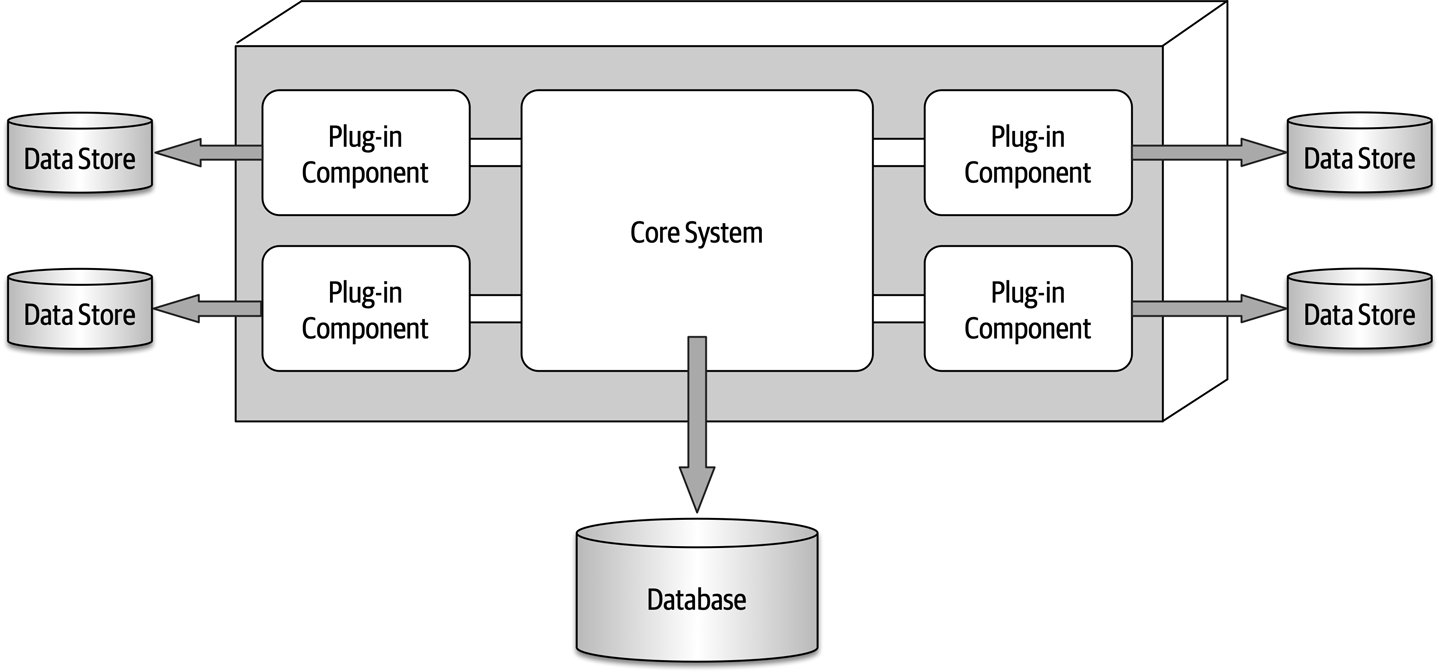

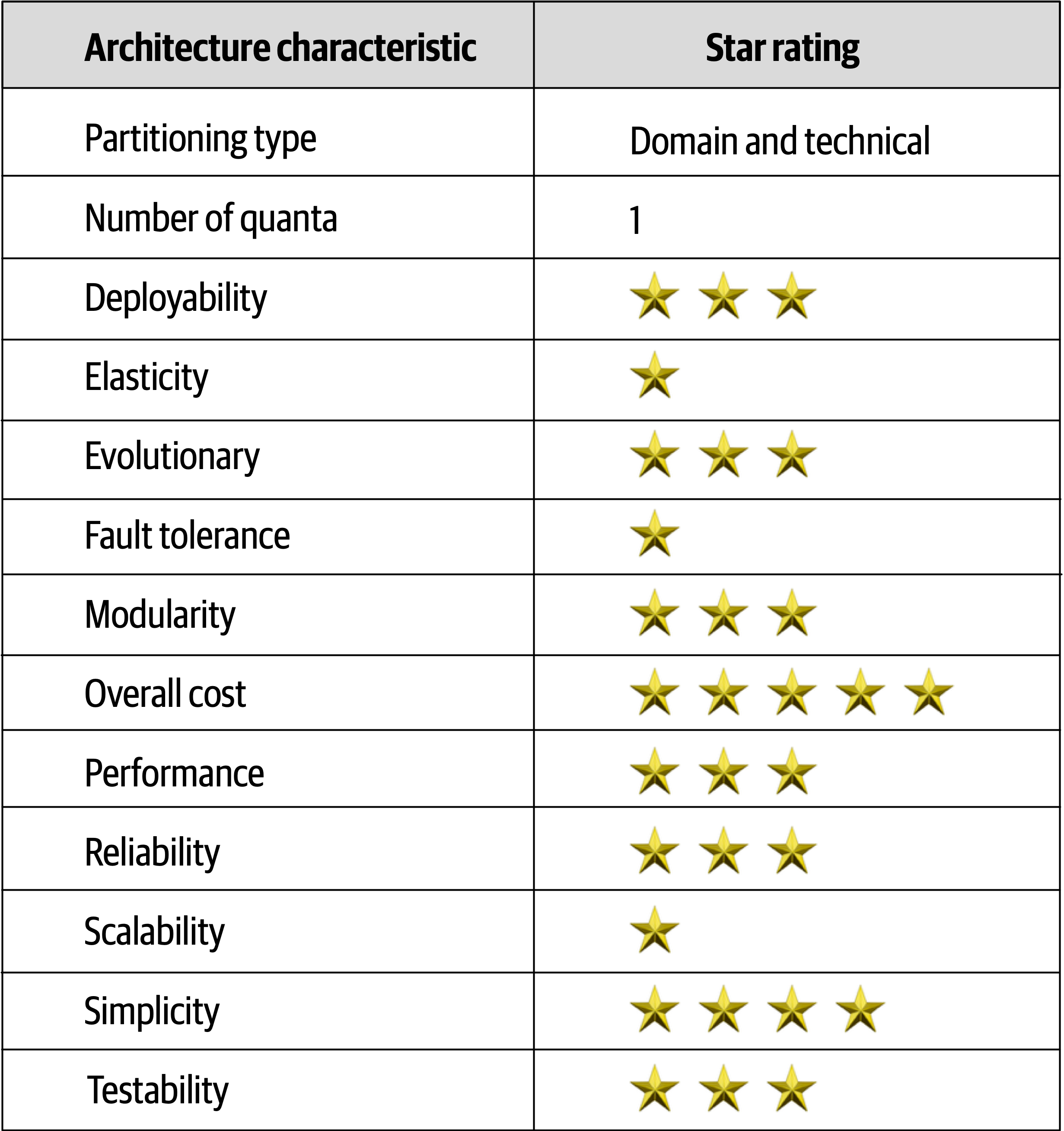

- 12. Microkernel Architecture Style

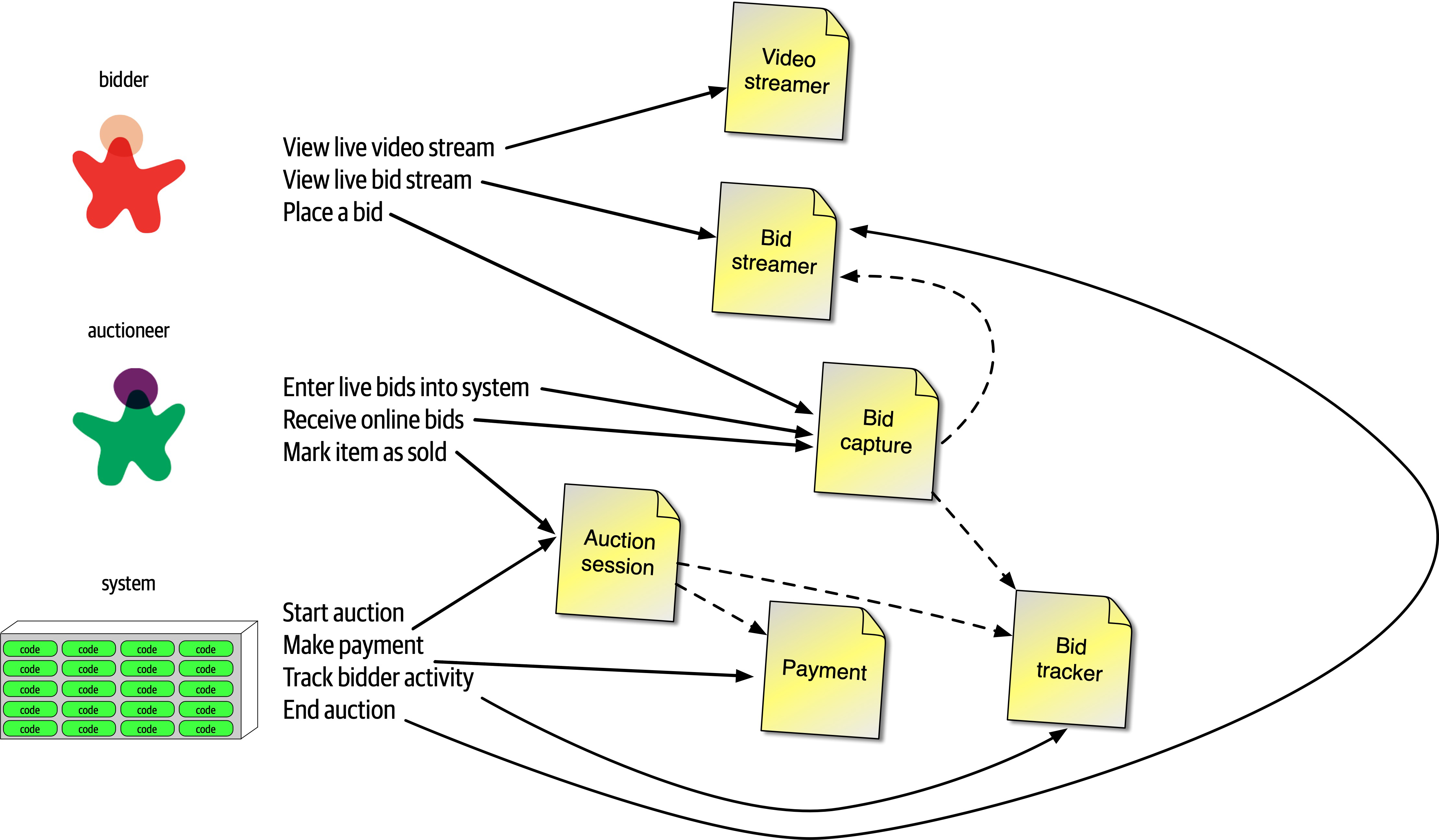

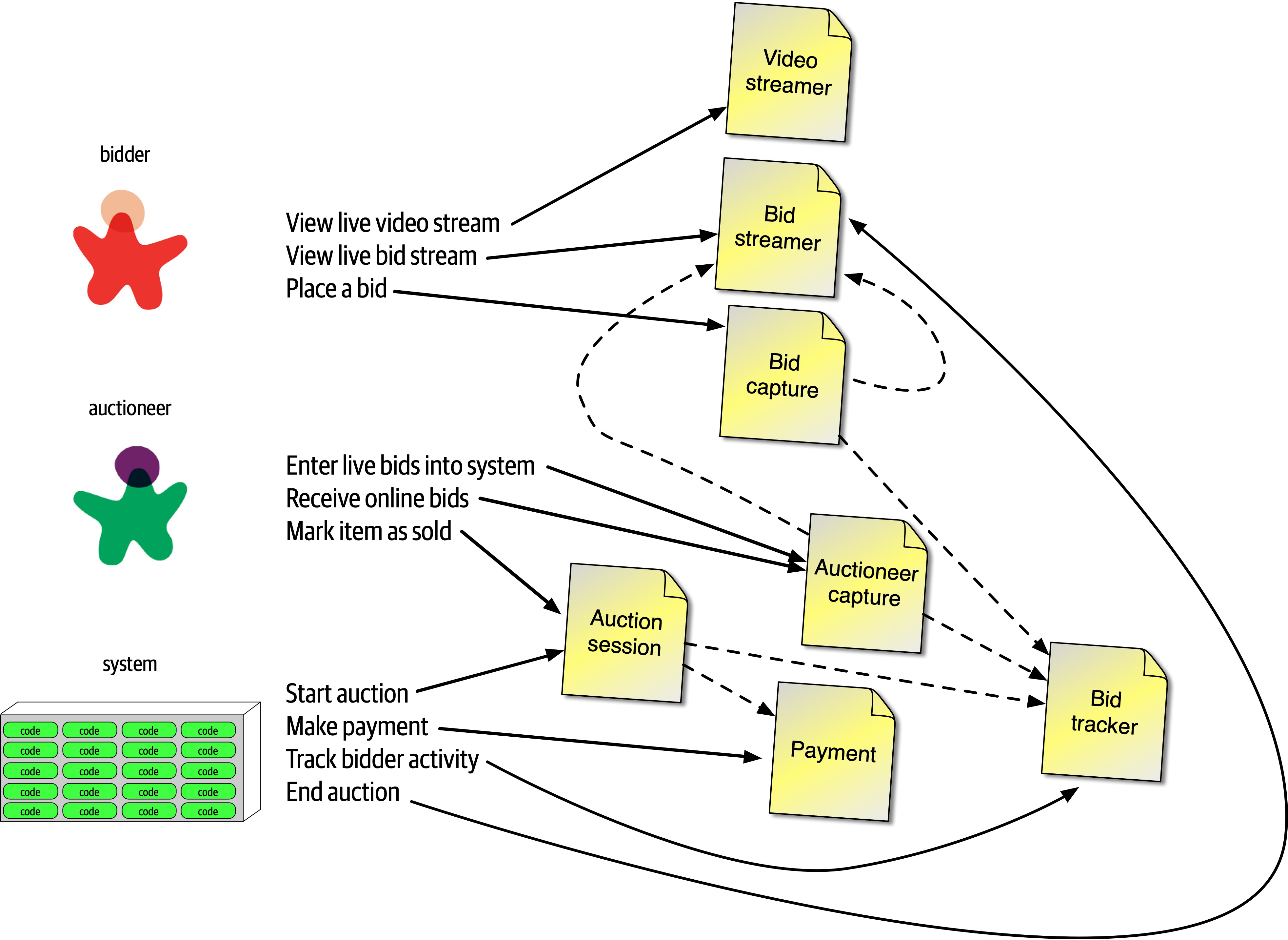

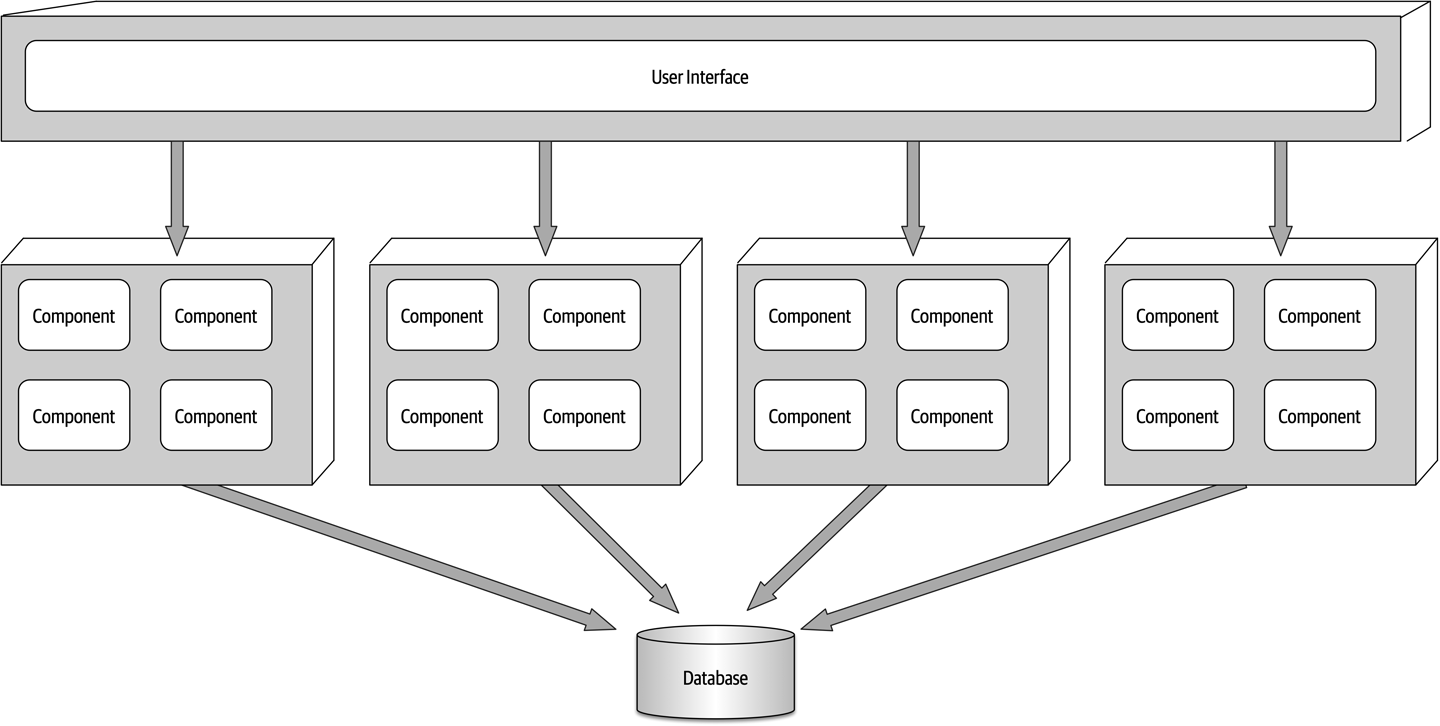

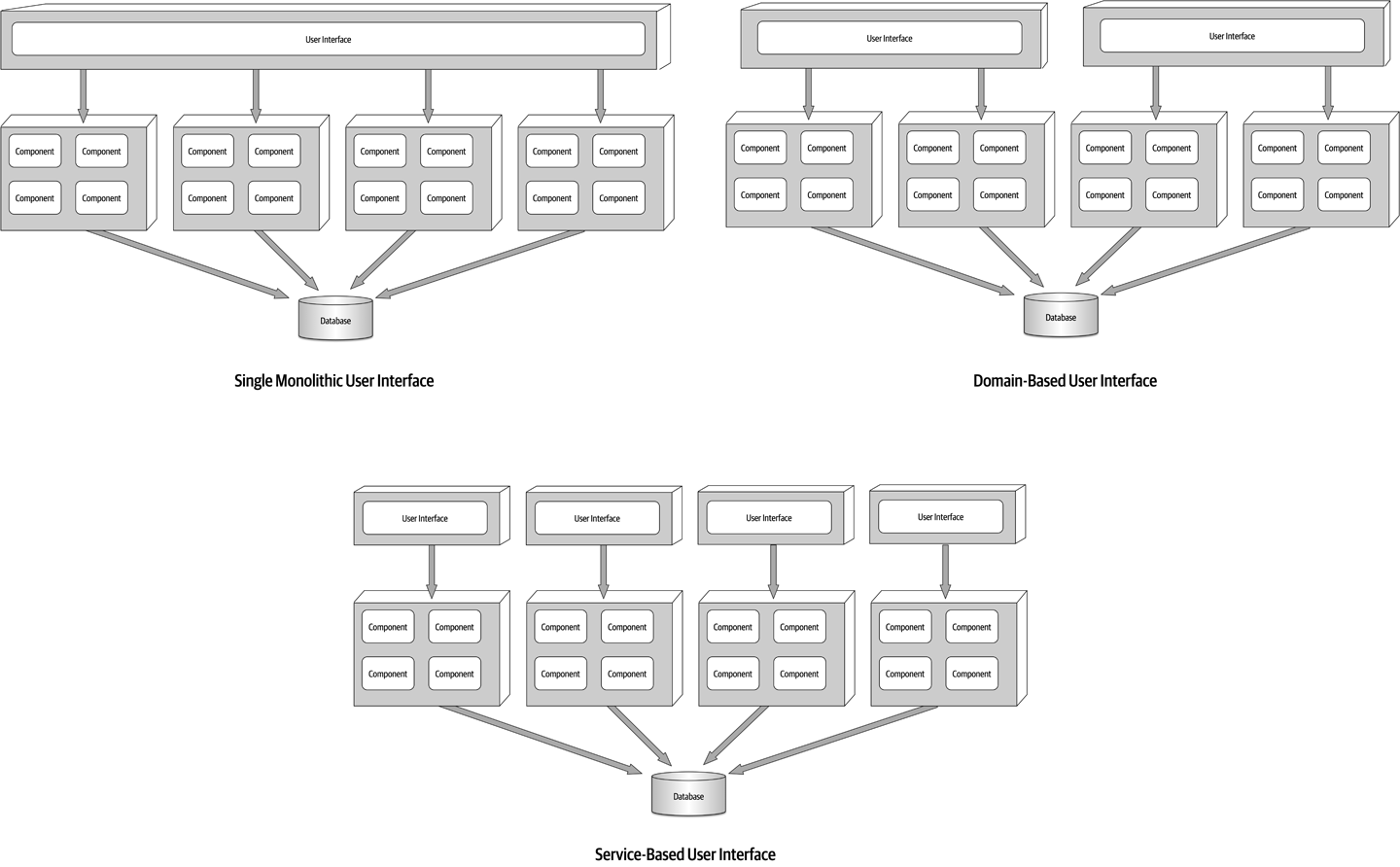

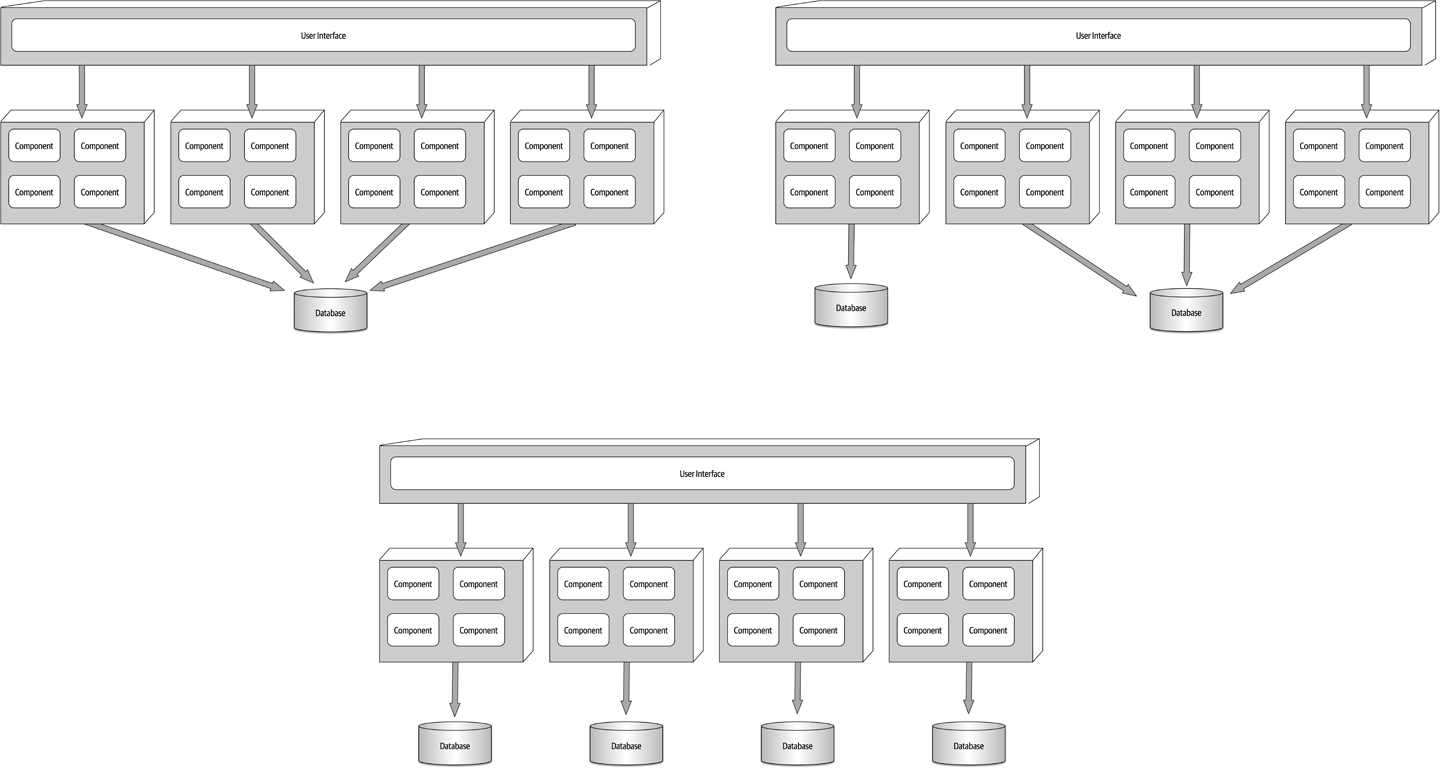

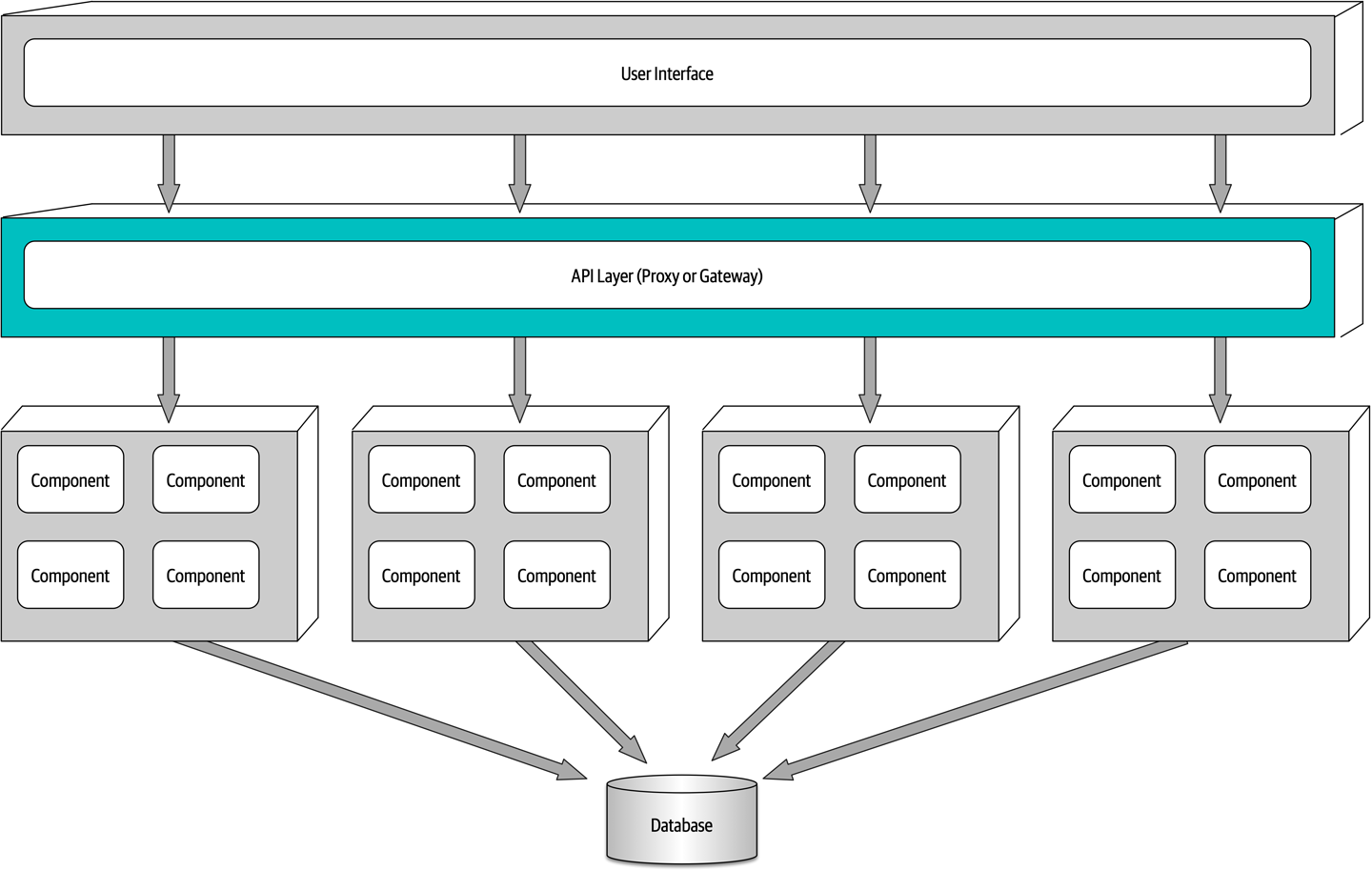

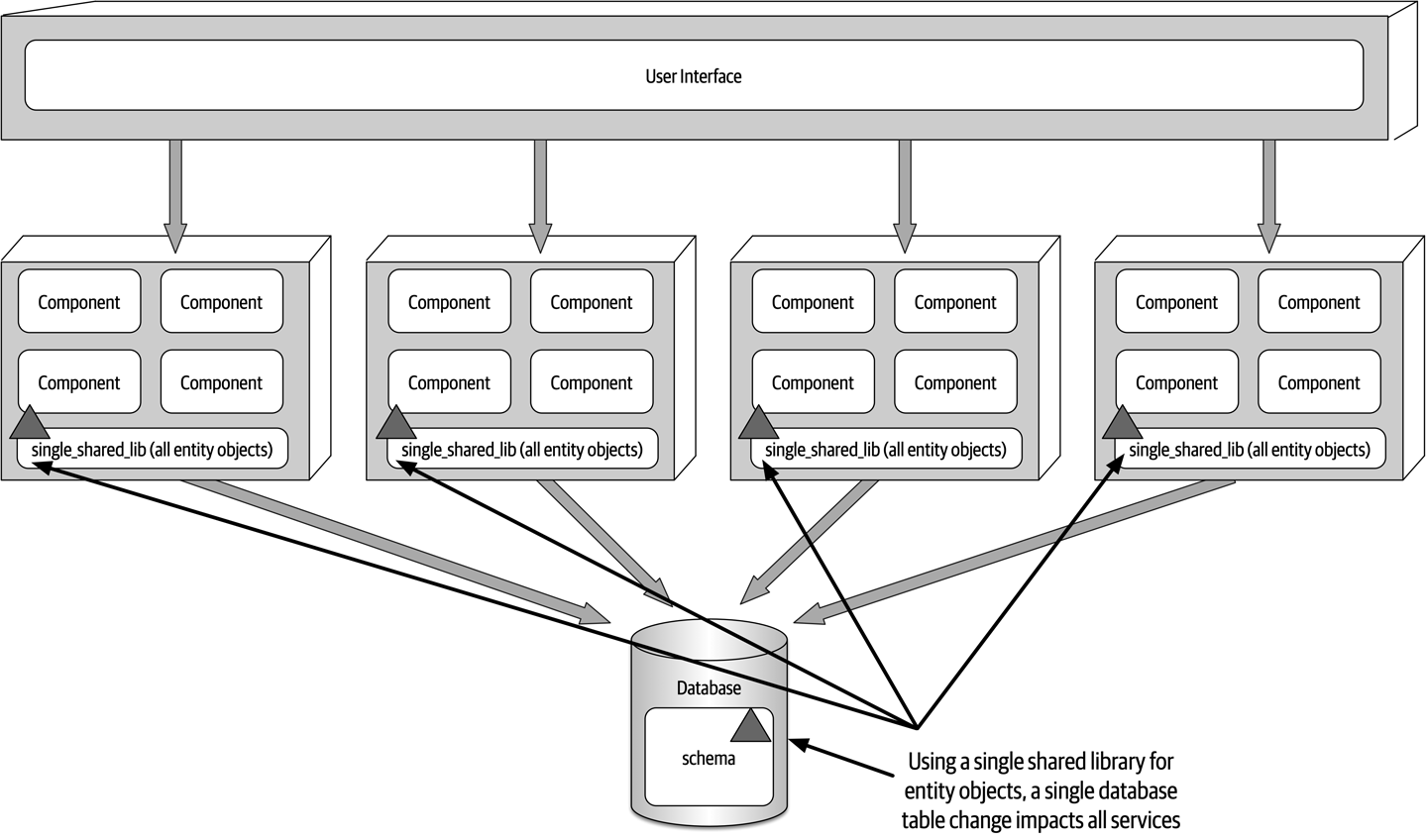

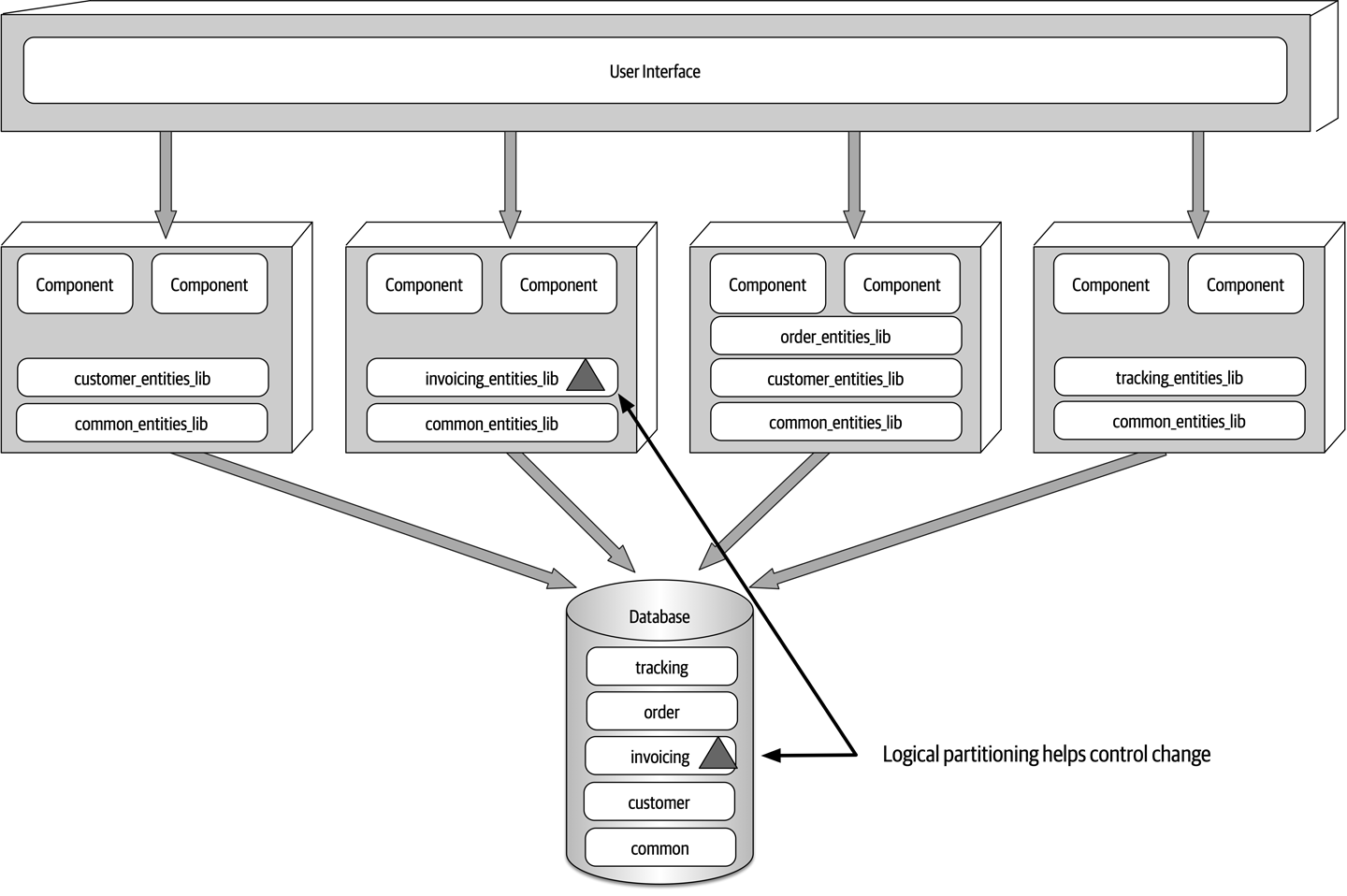

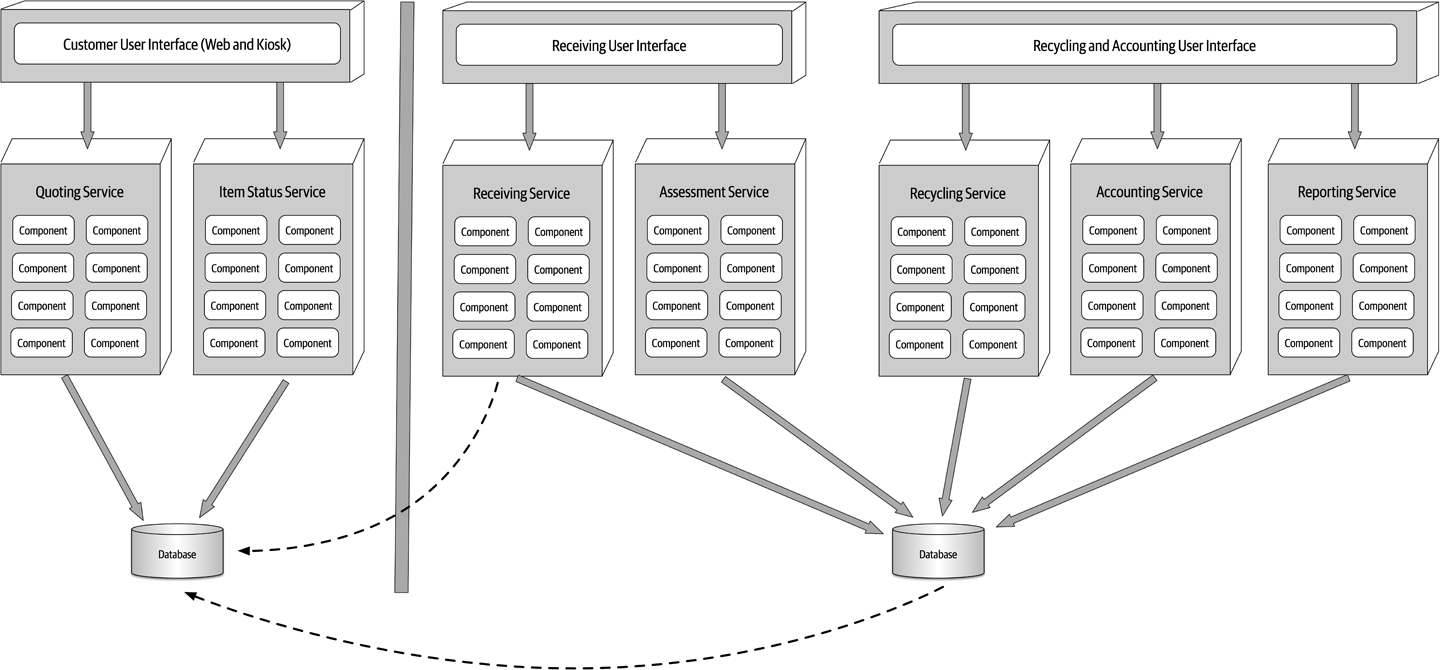

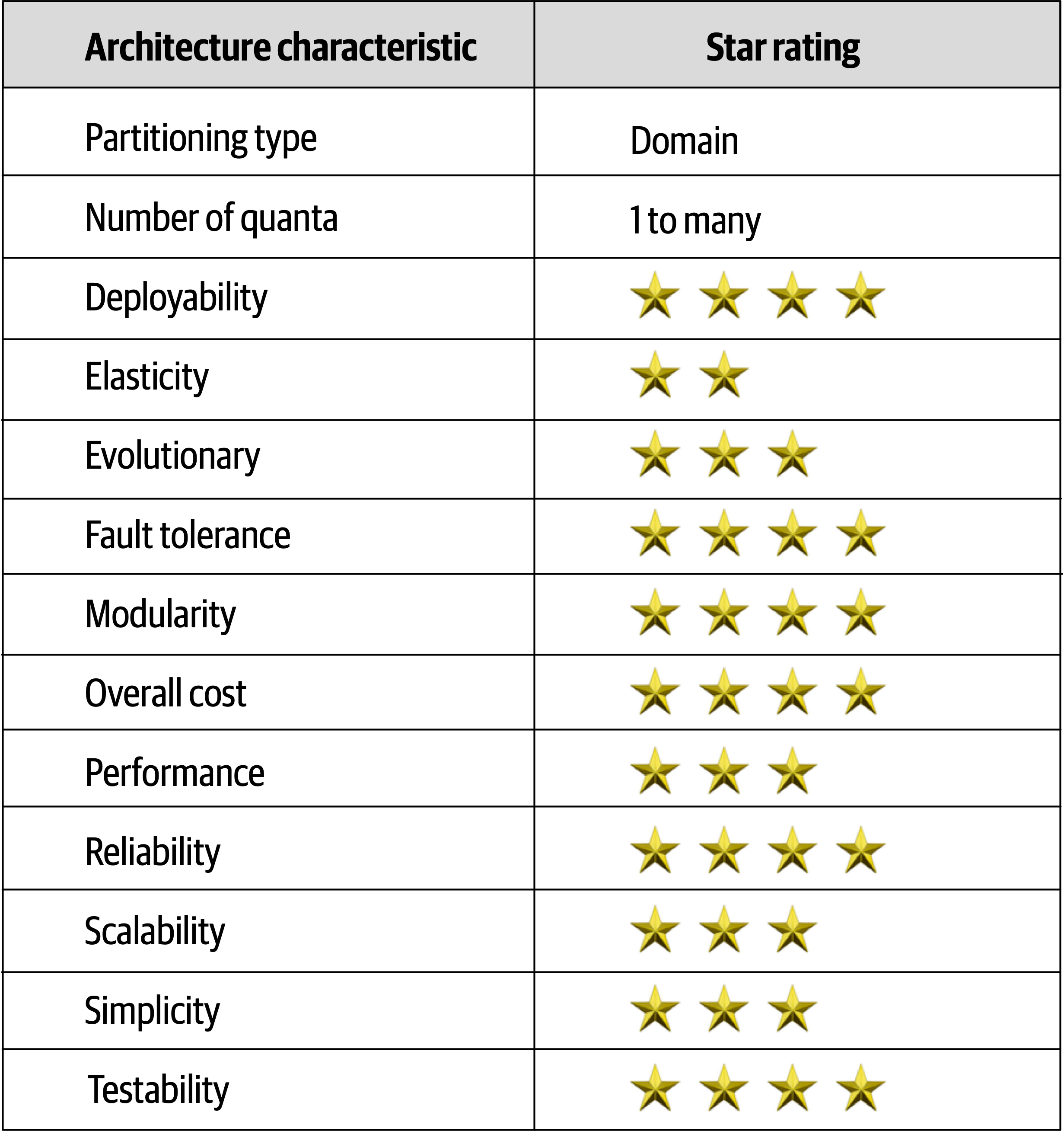

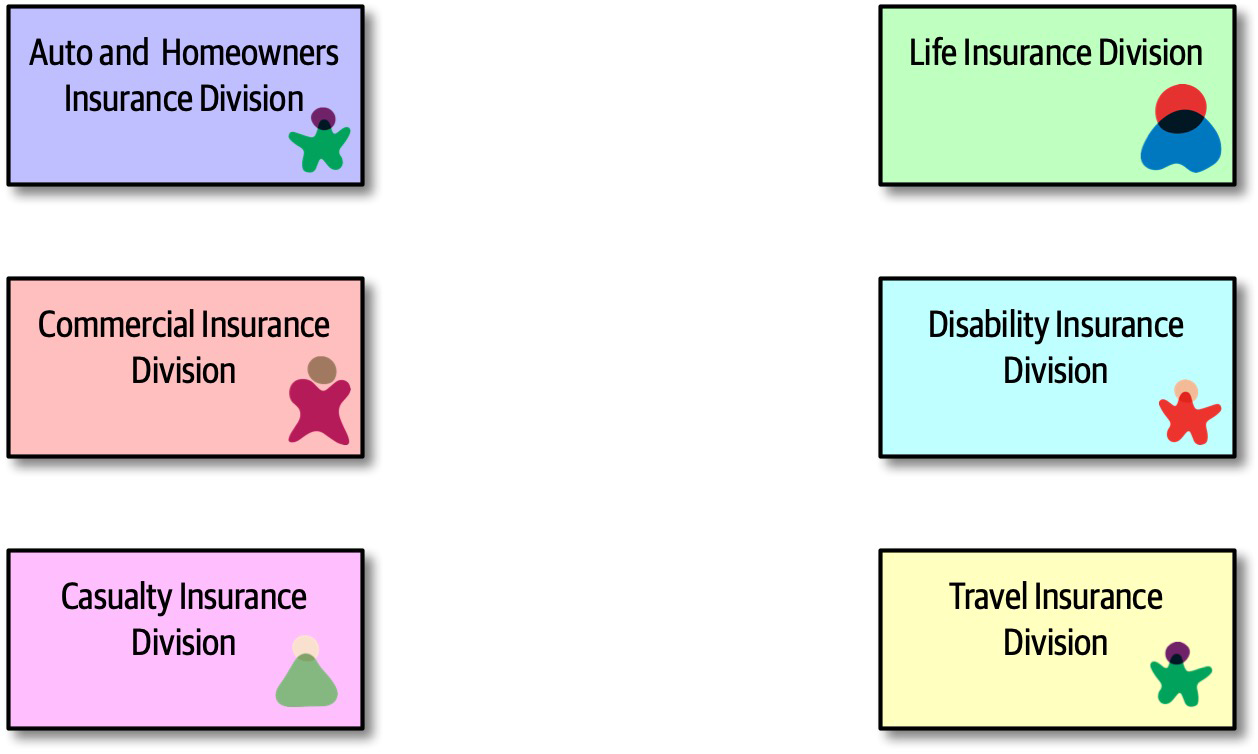

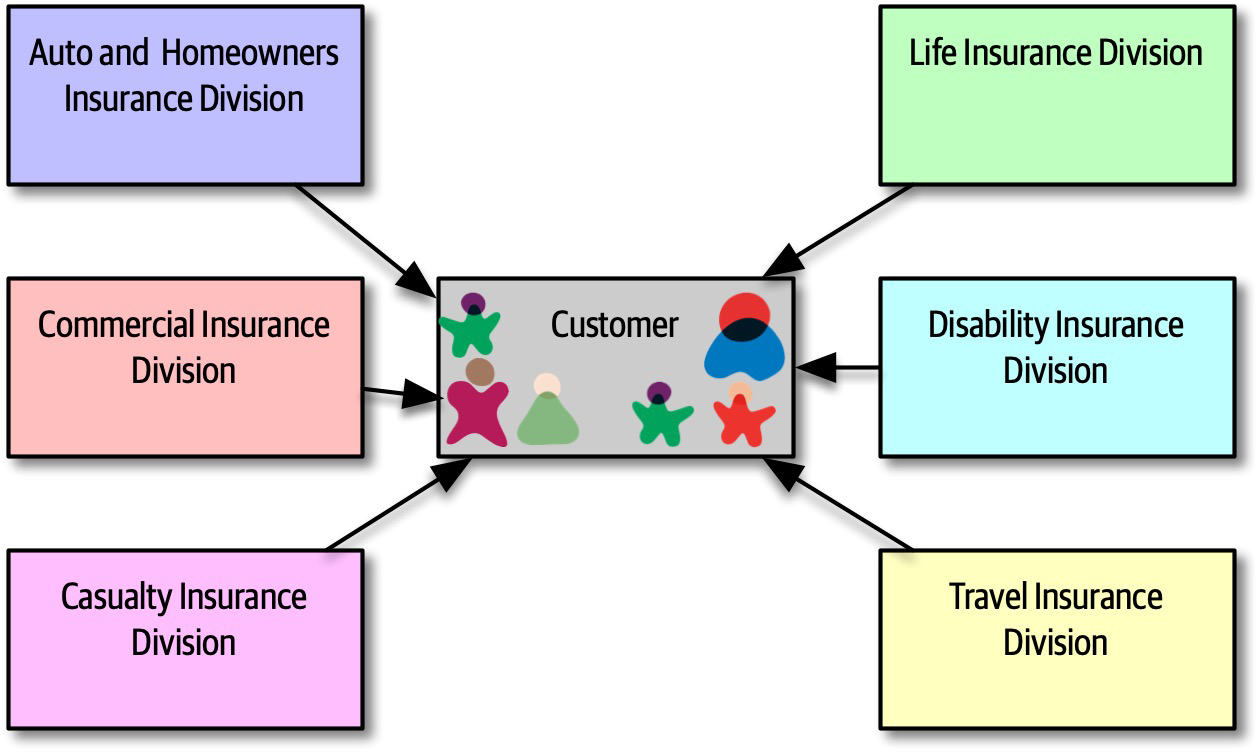

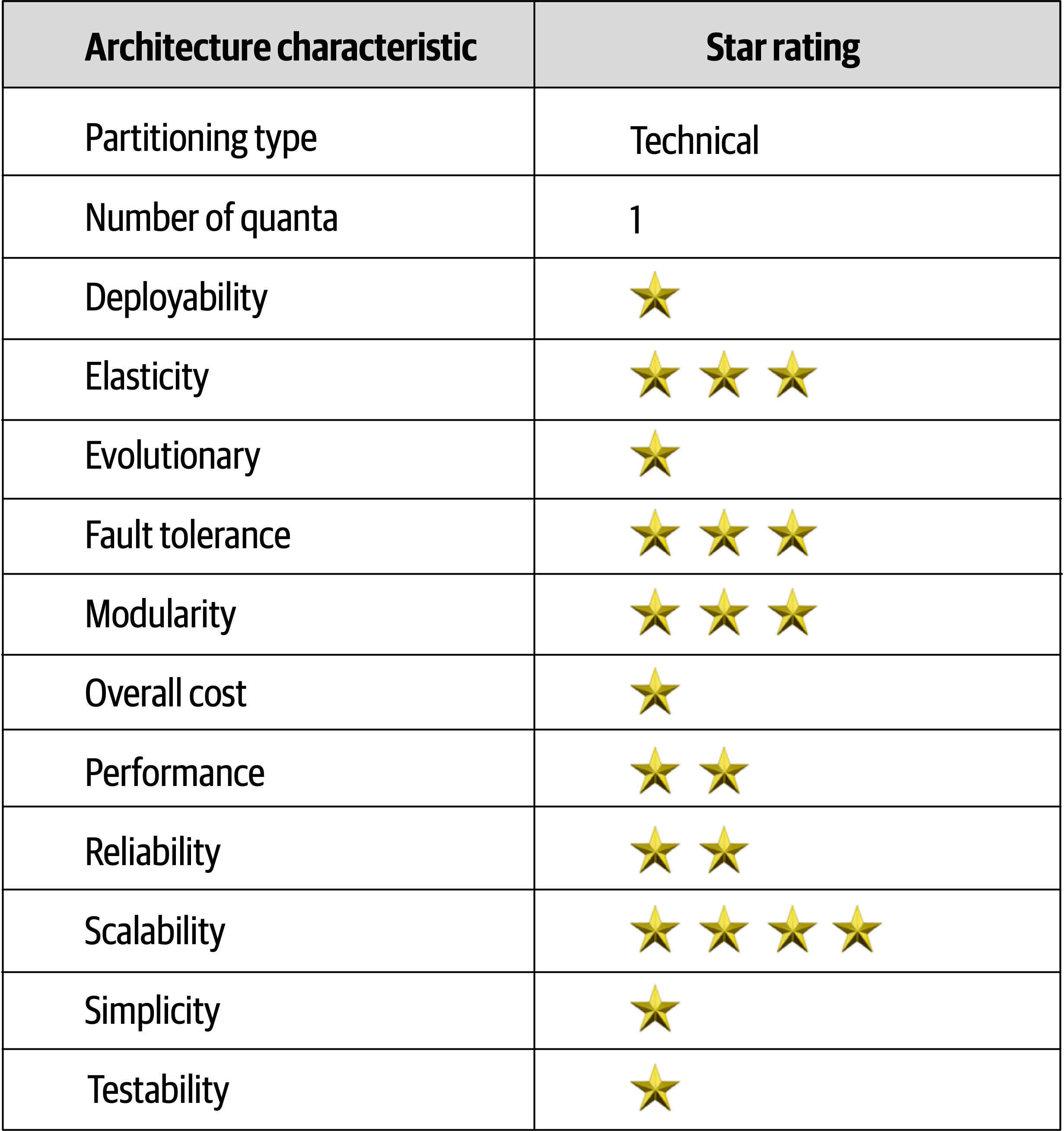

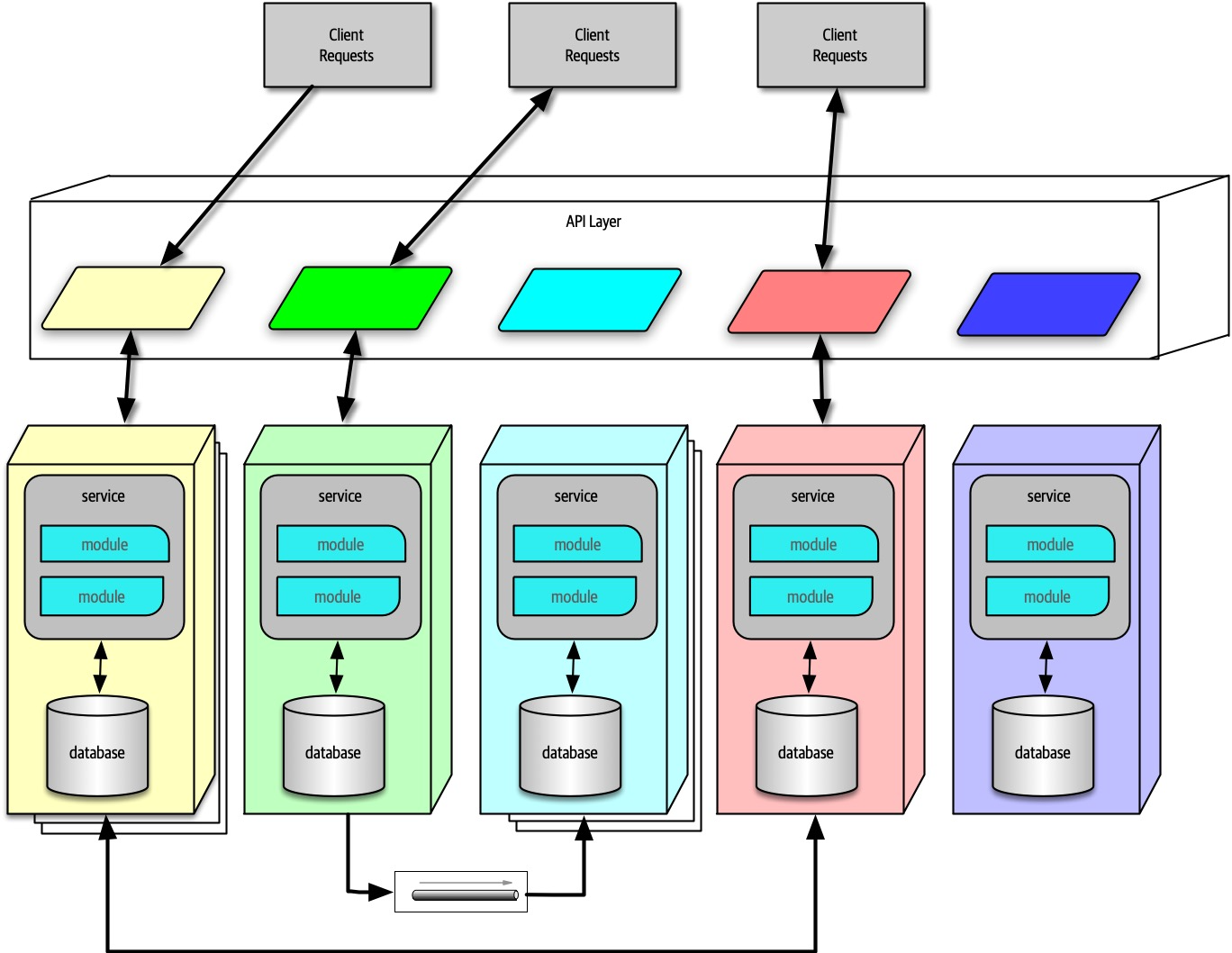

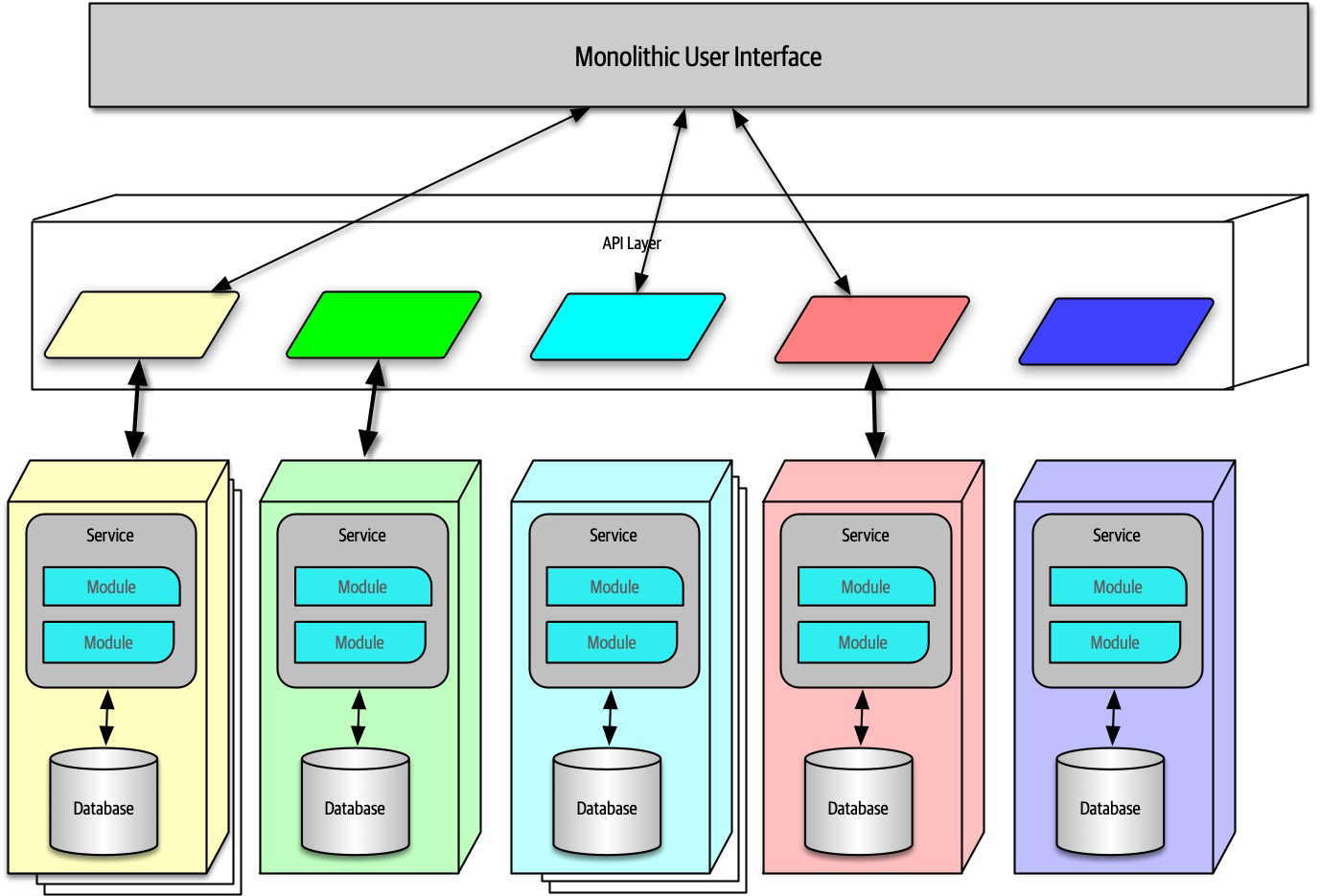

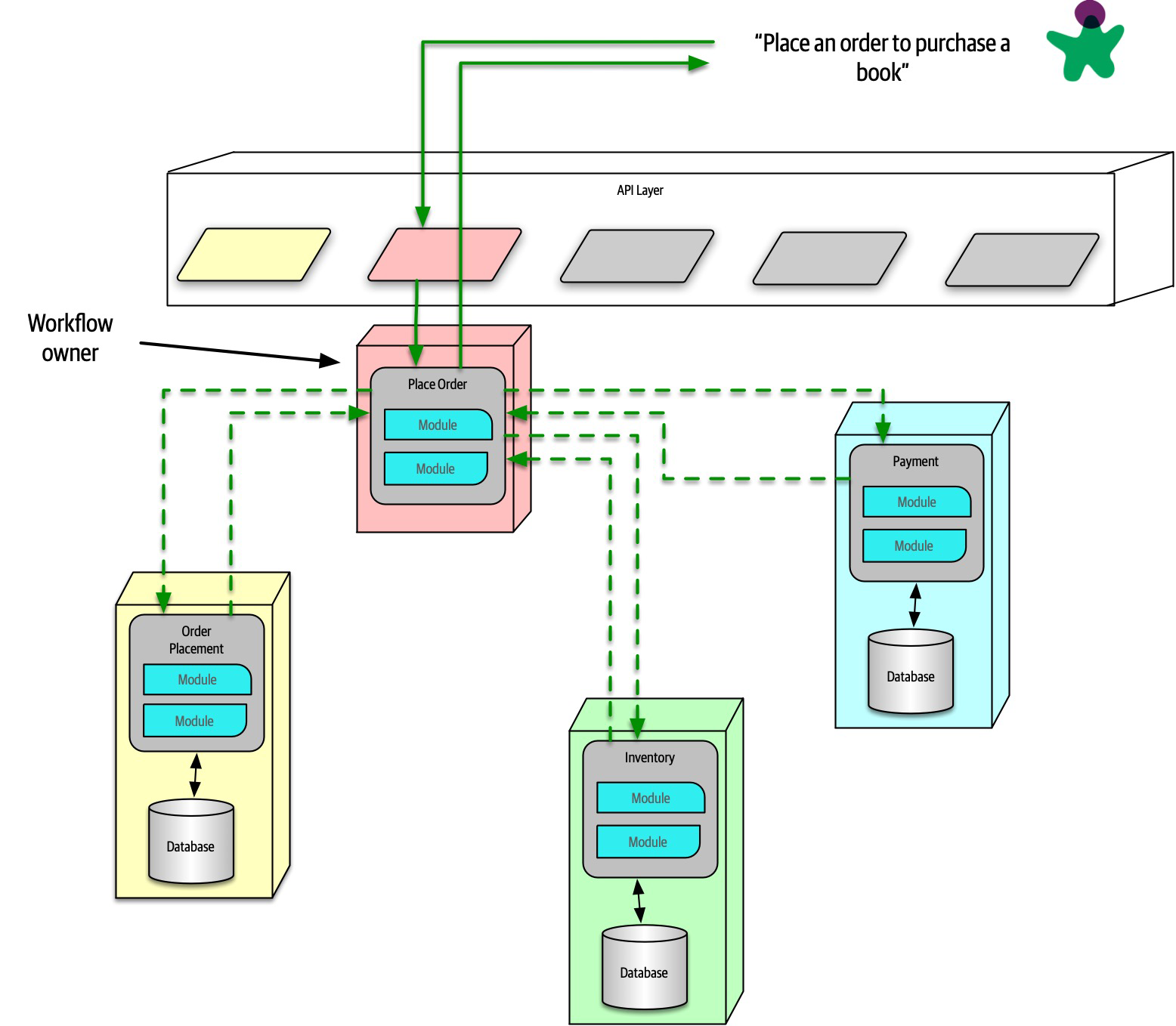

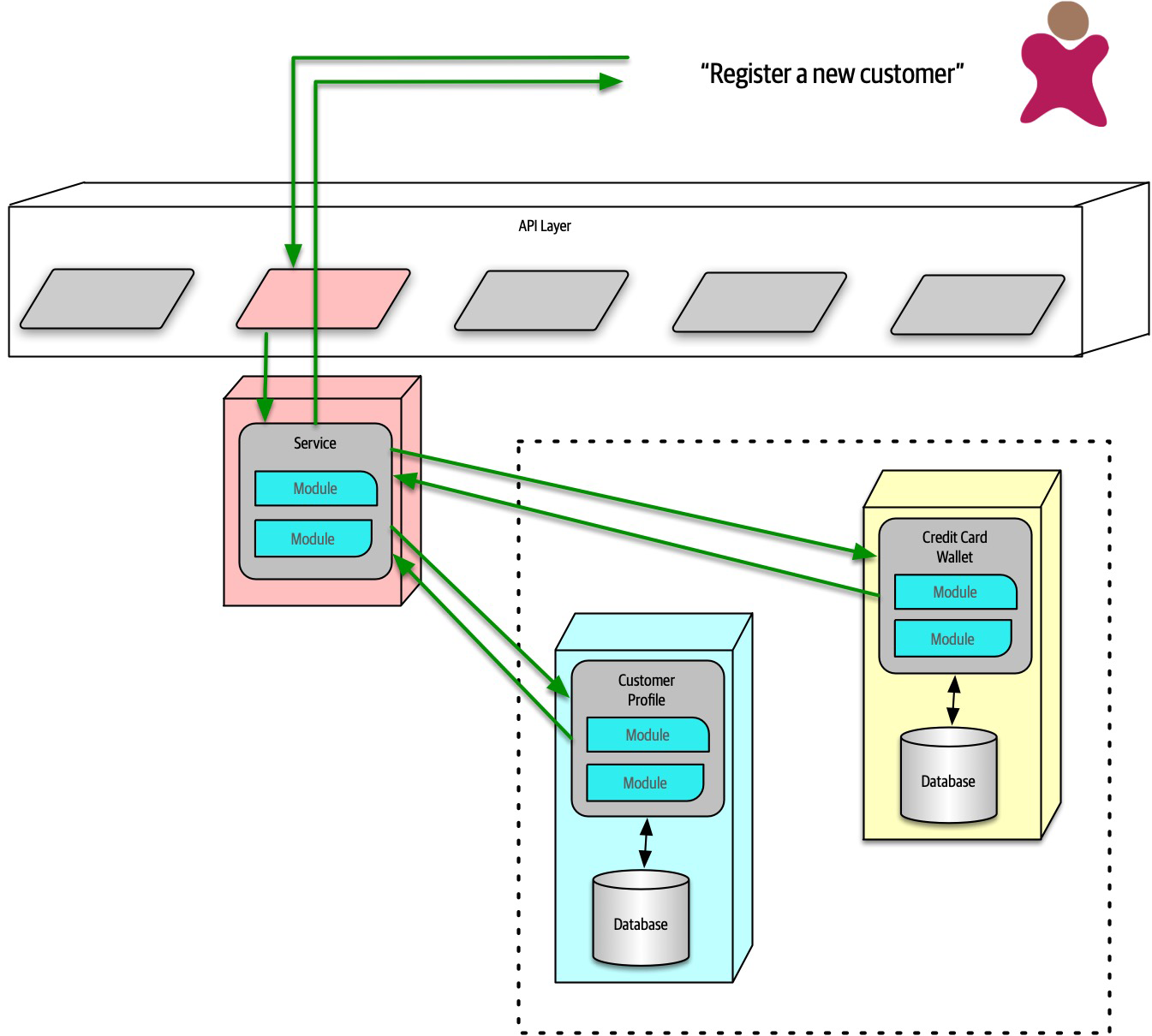

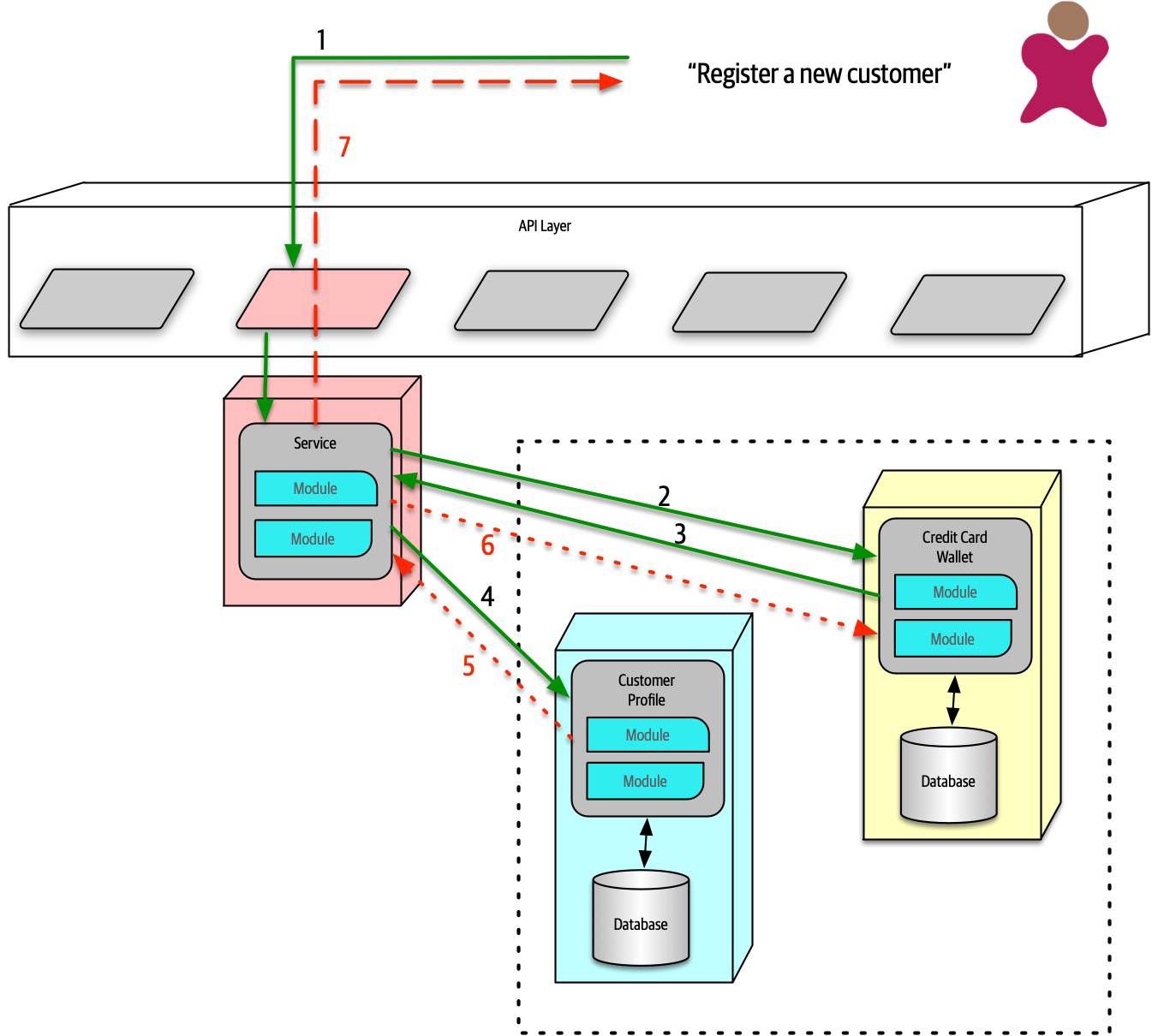

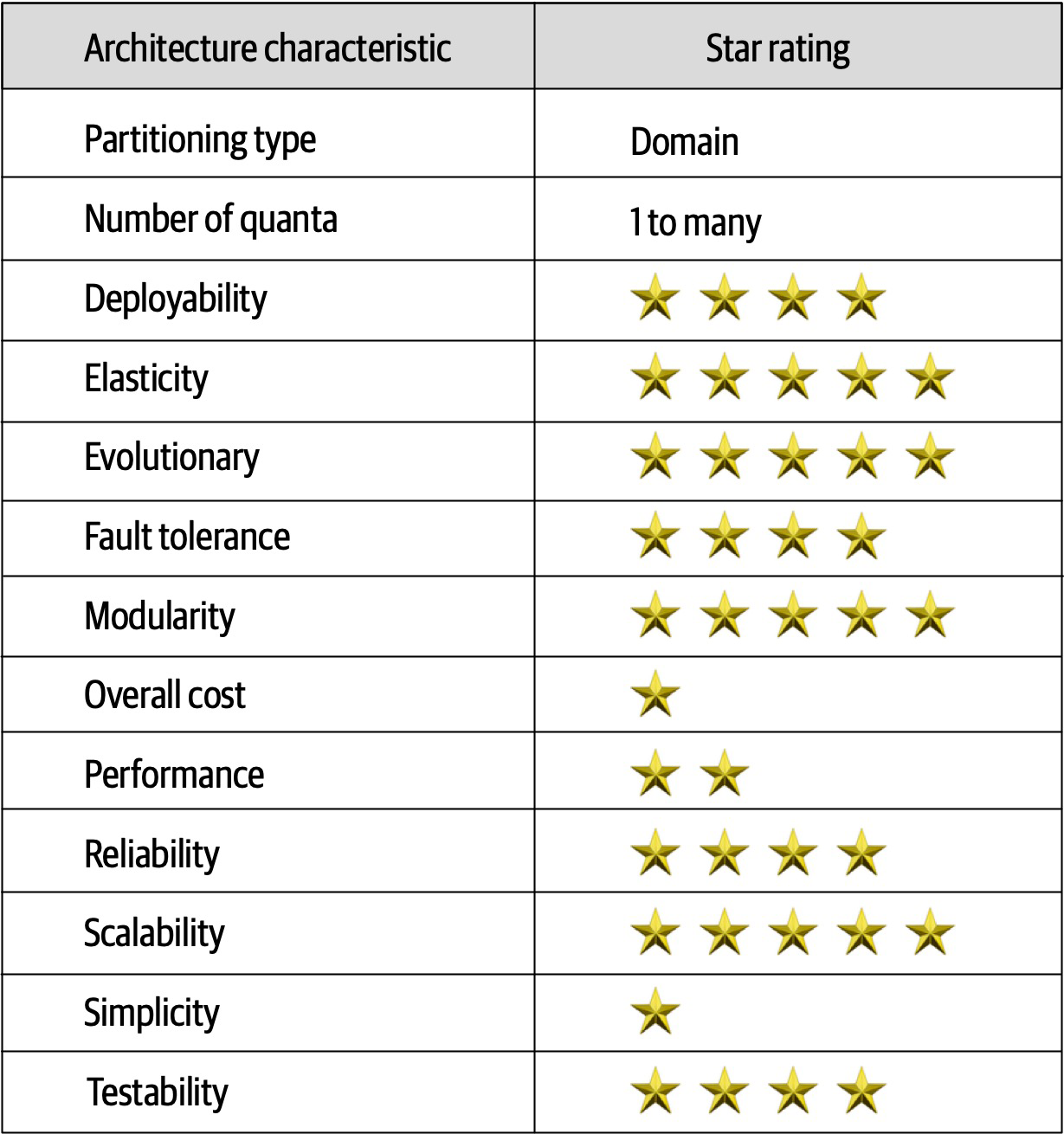

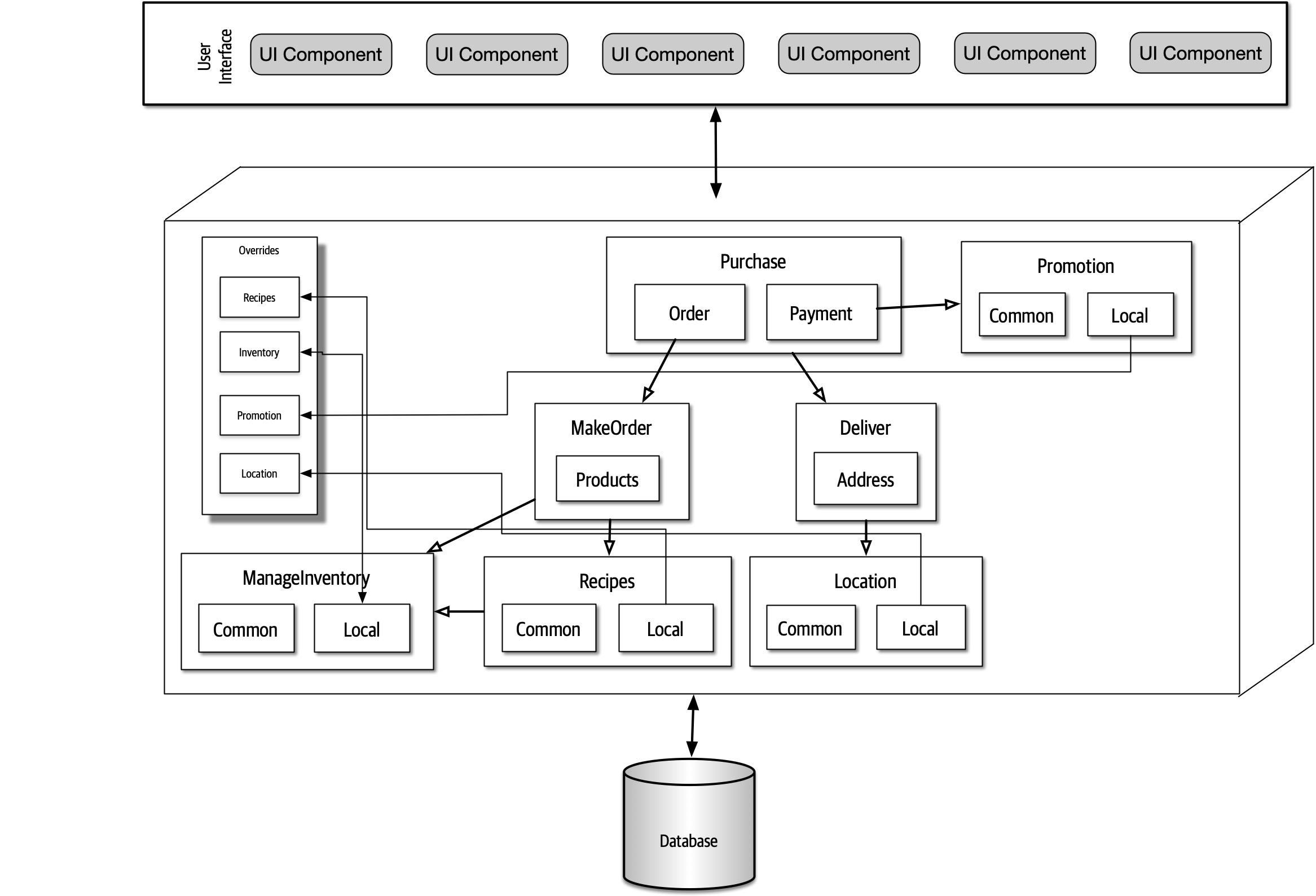

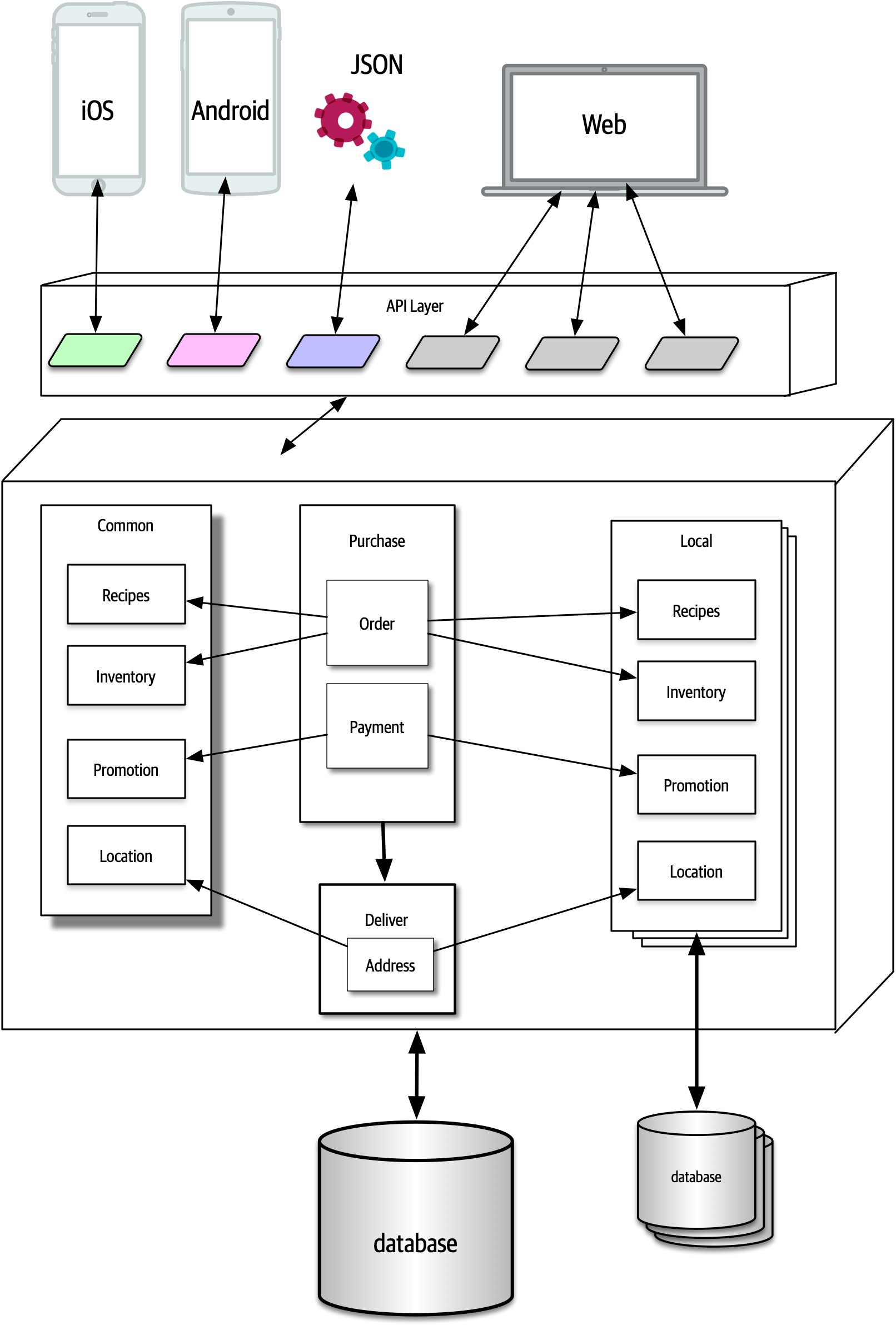

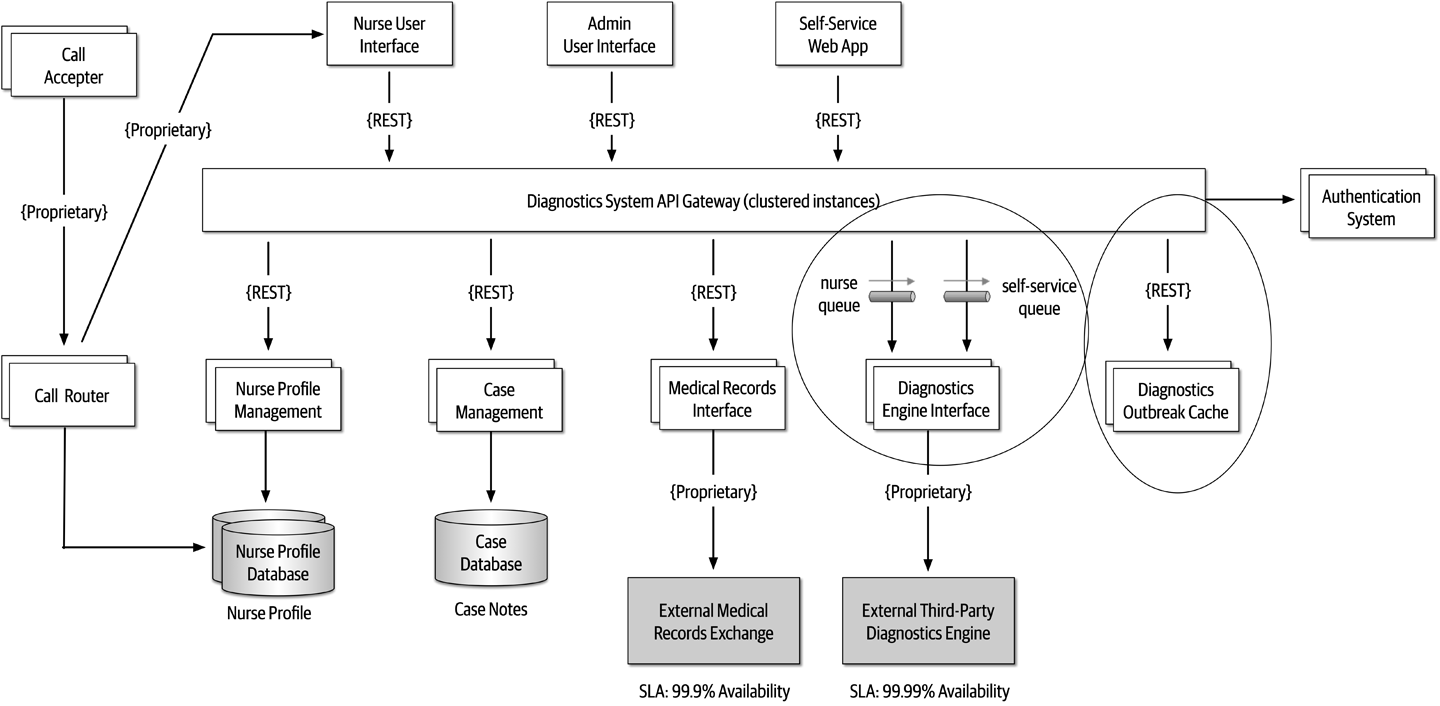

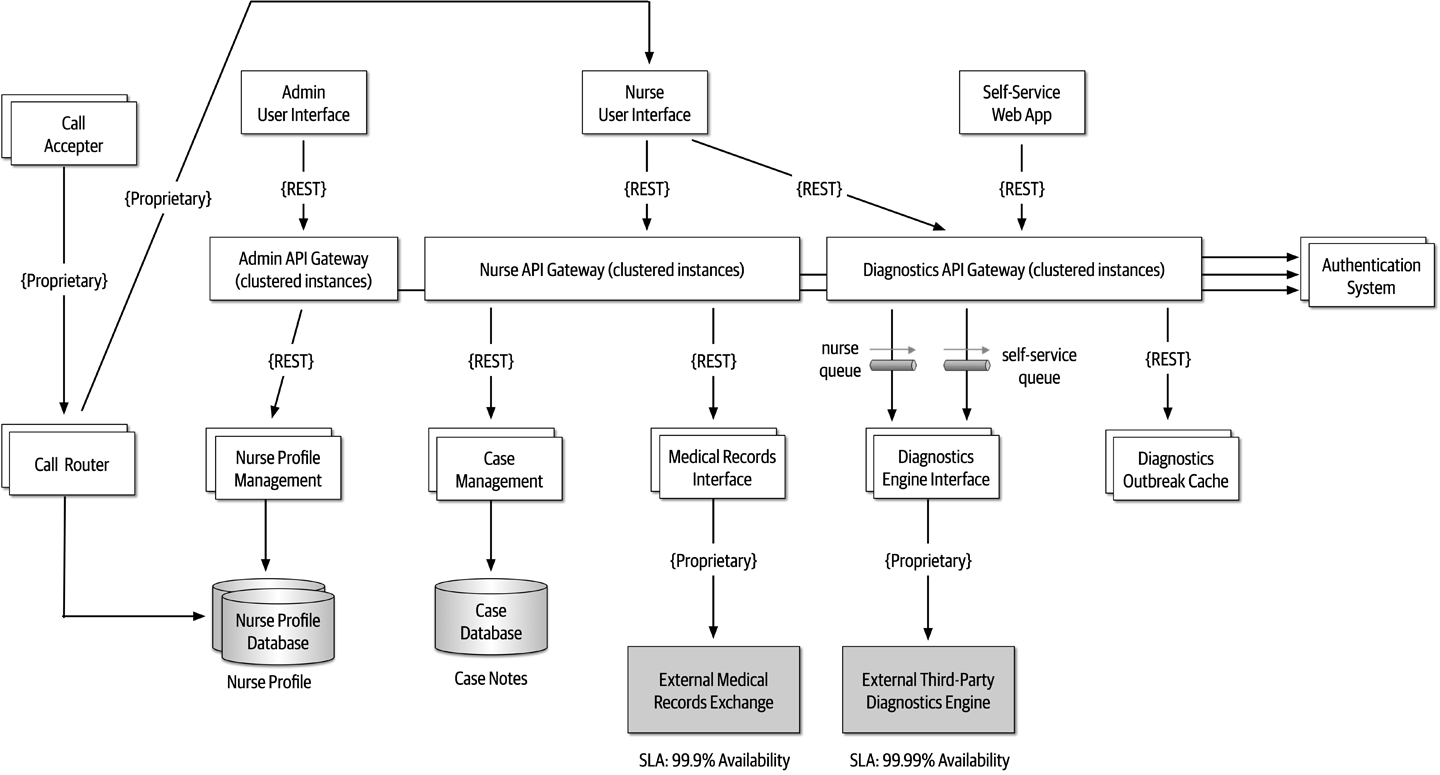

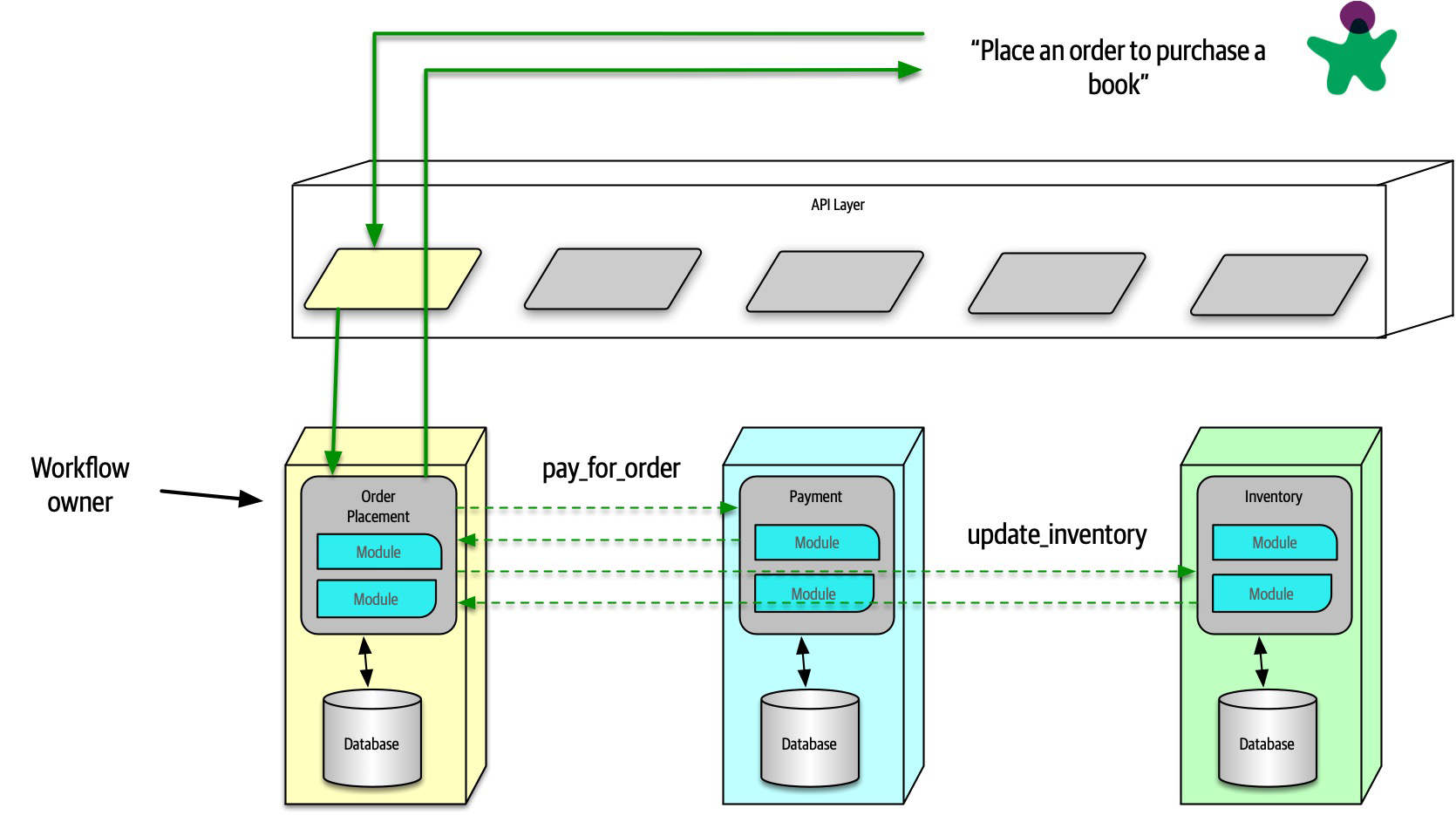

- 13. Service-Based Architecture Style

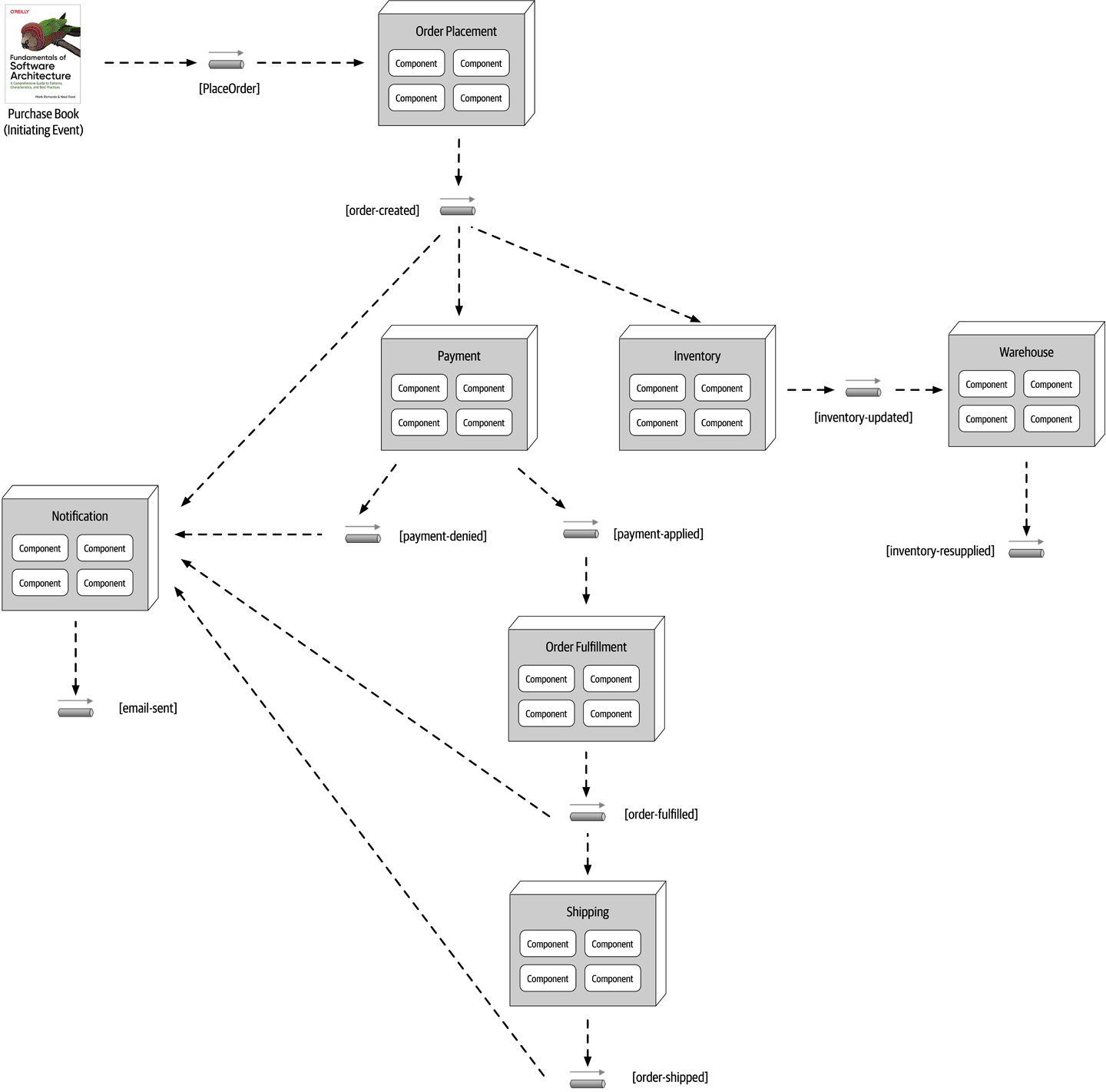

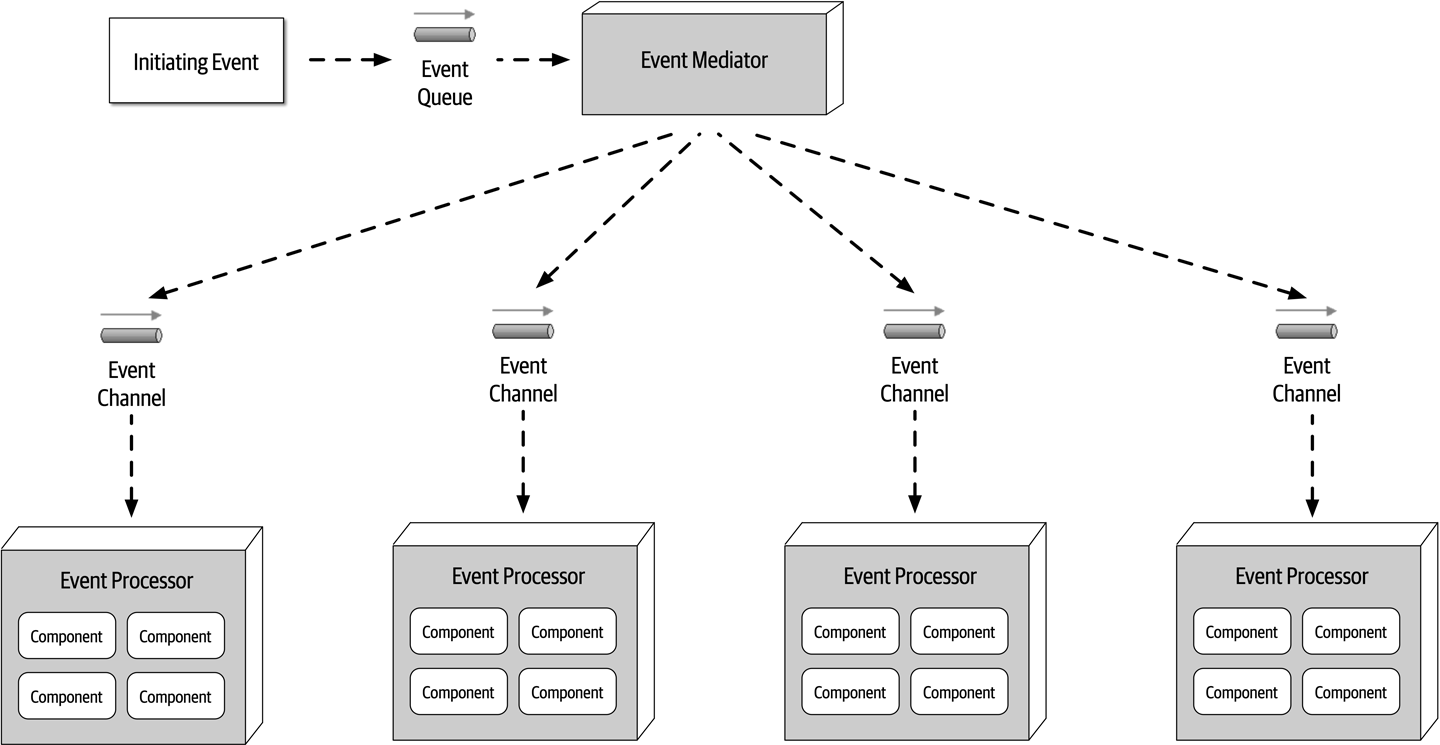

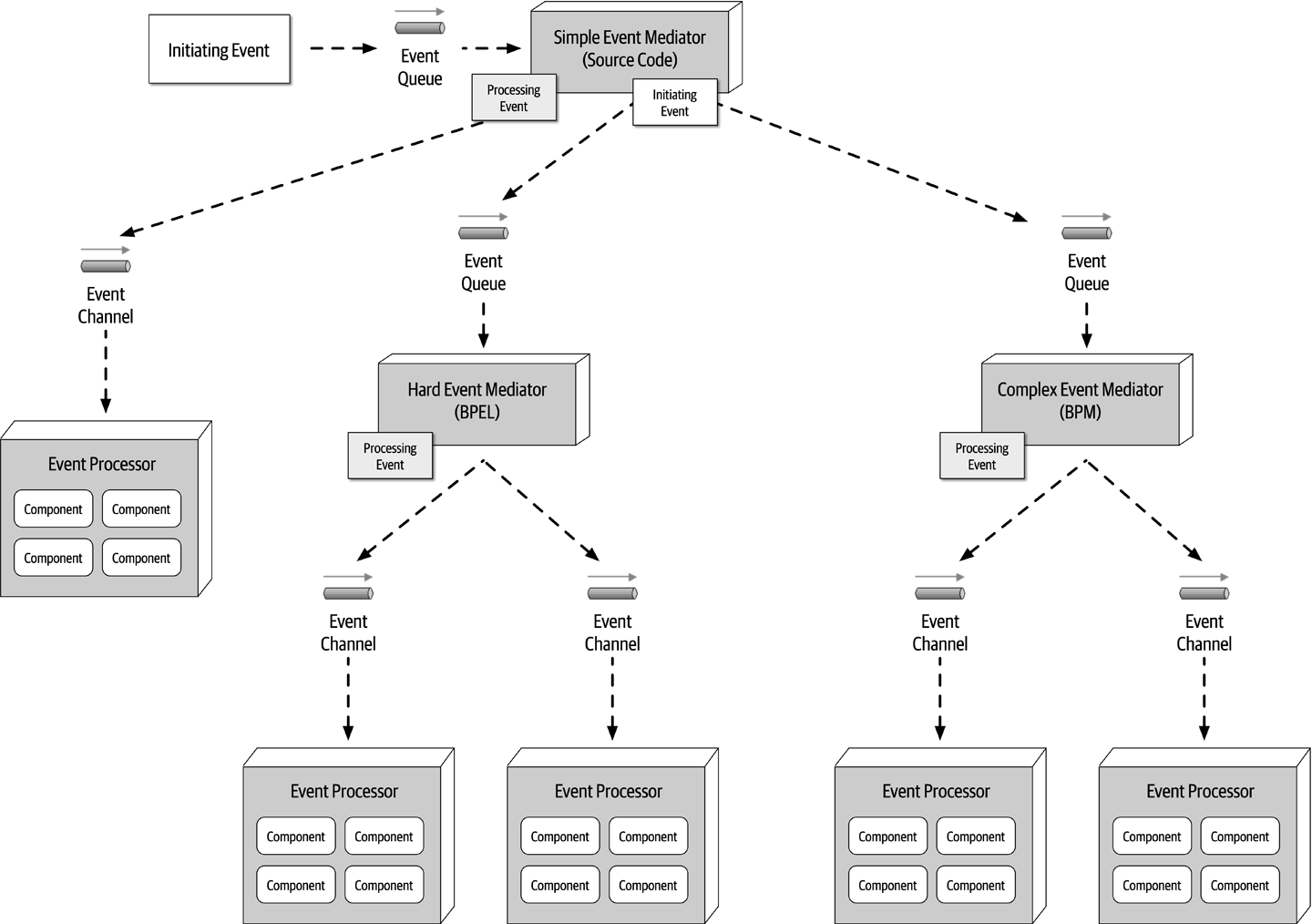

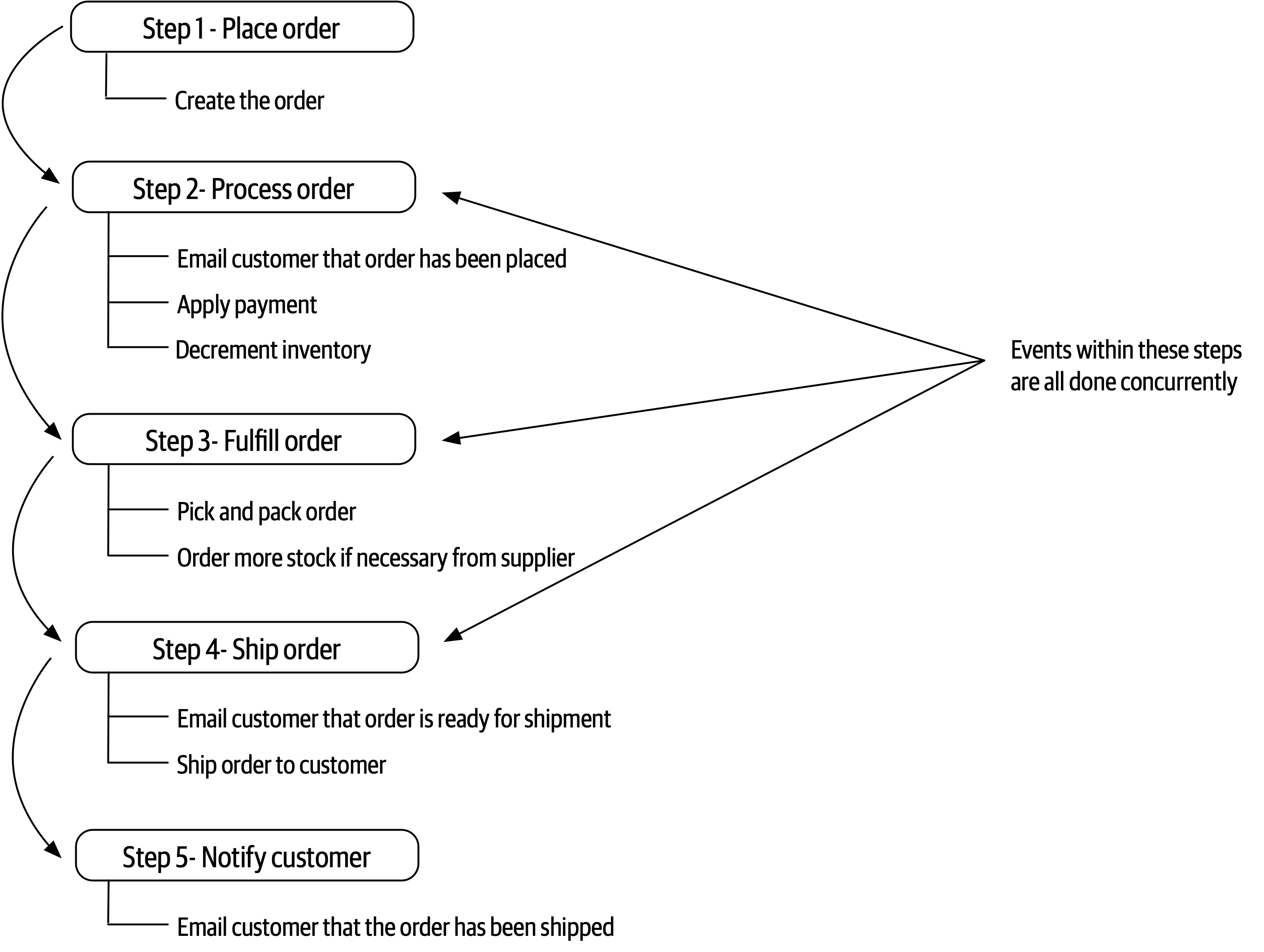

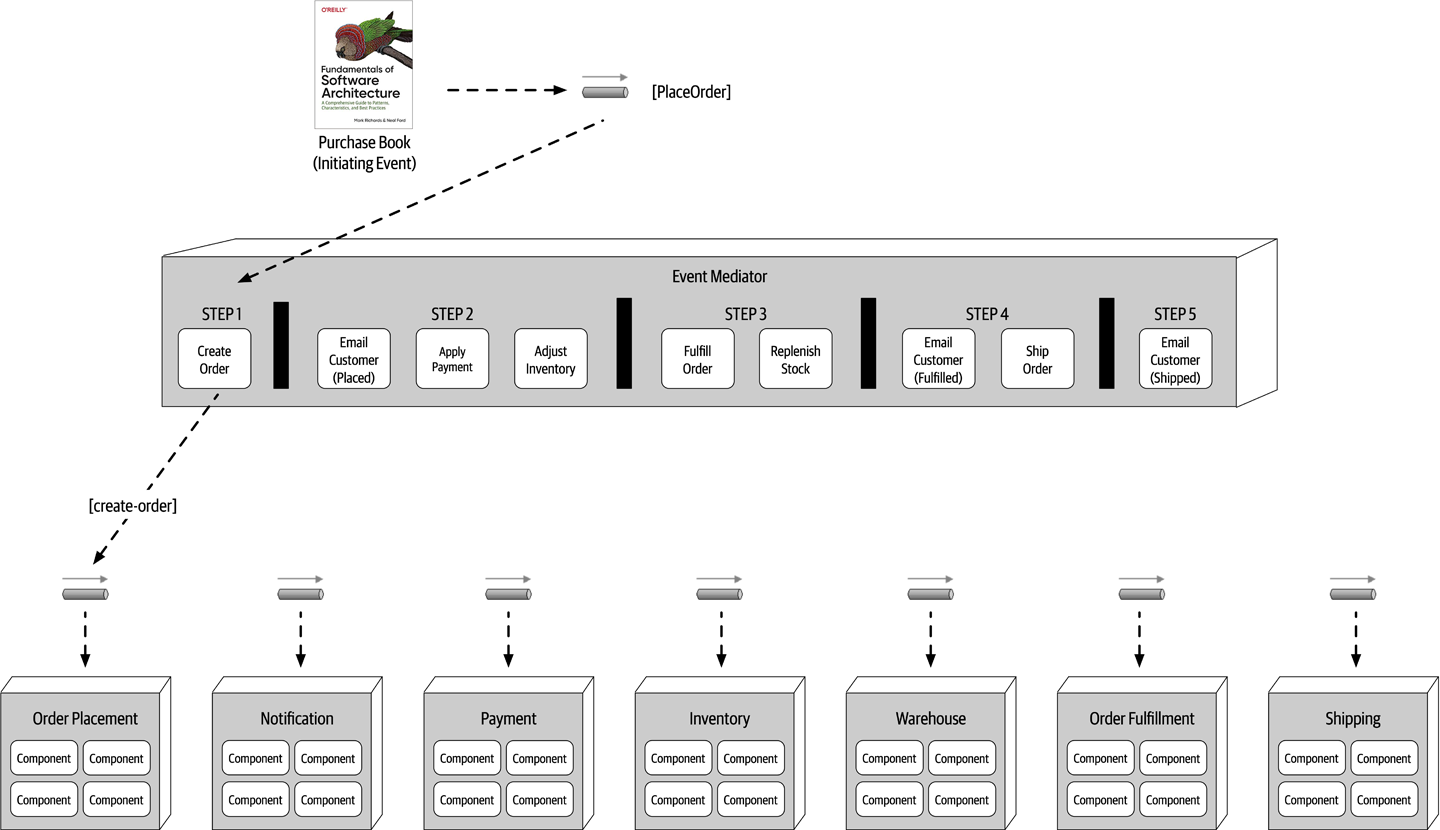

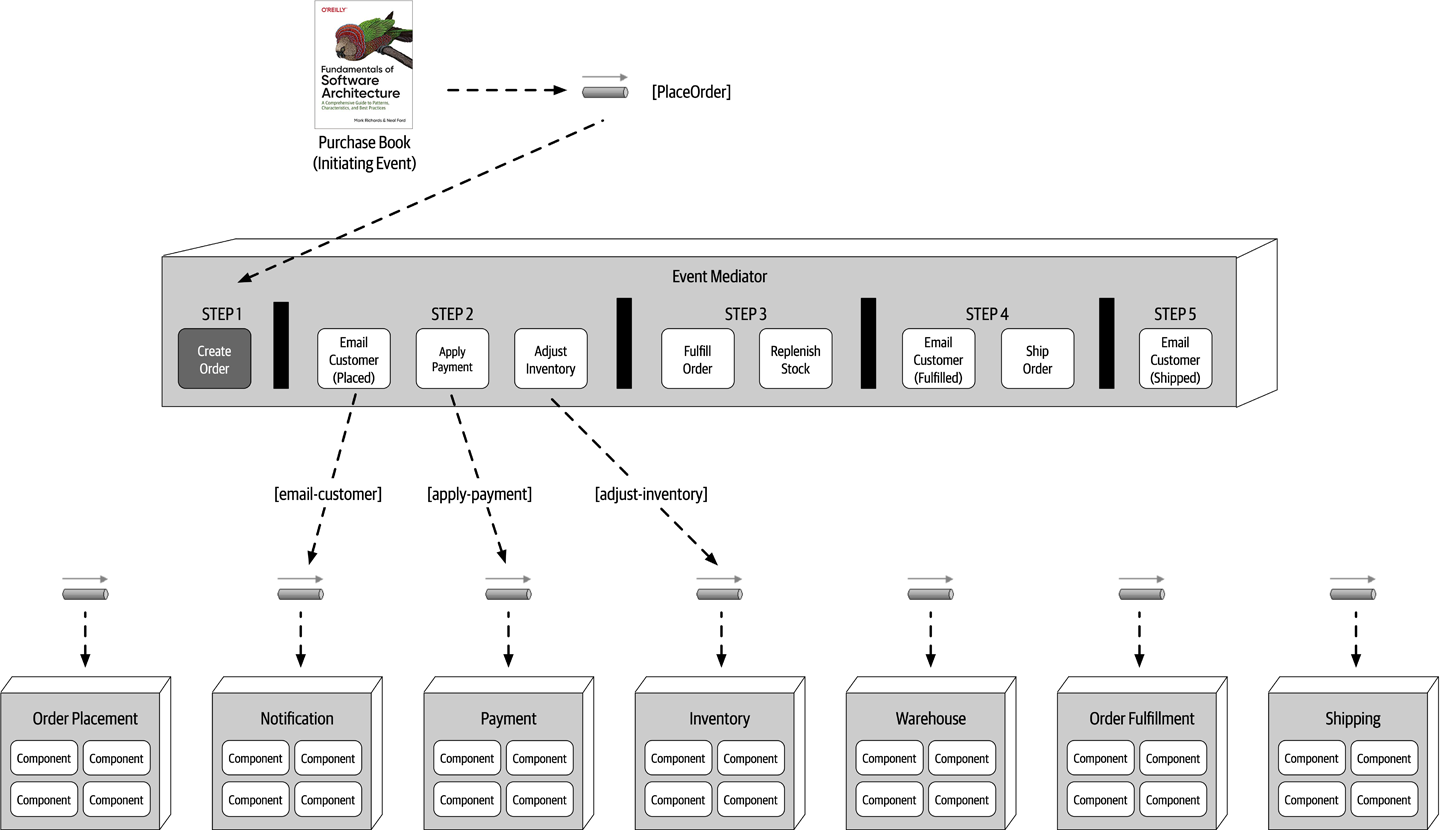

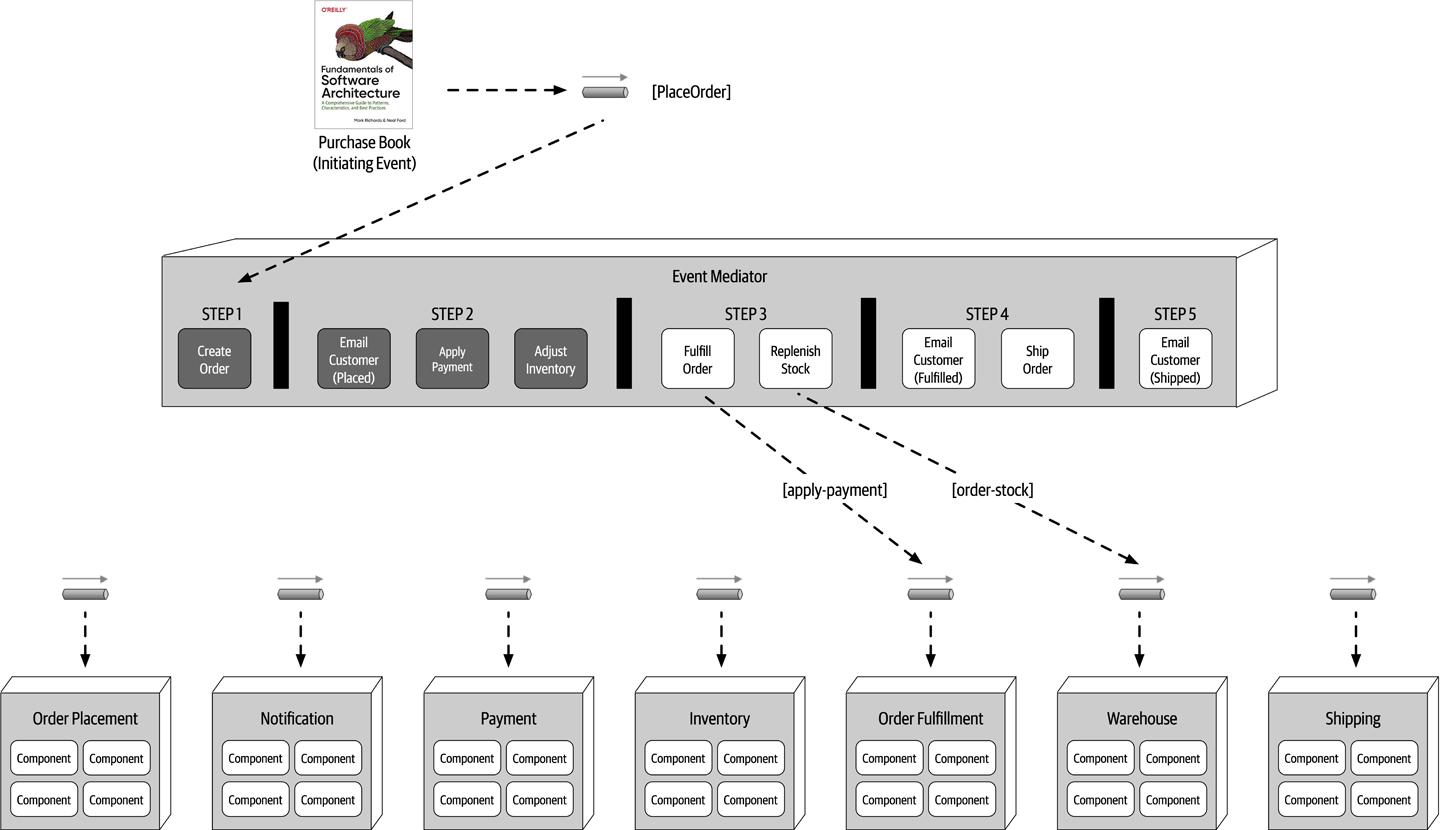

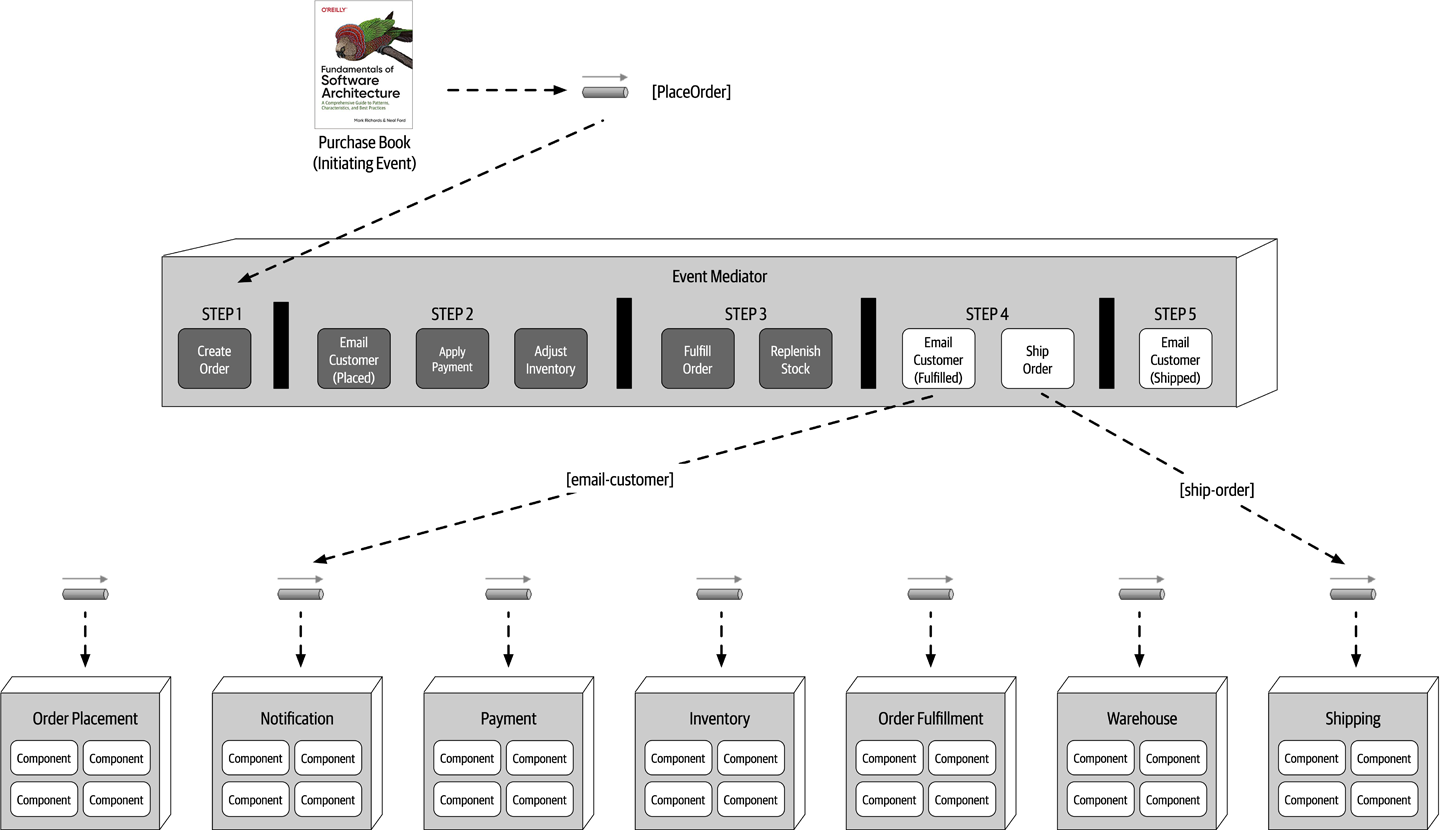

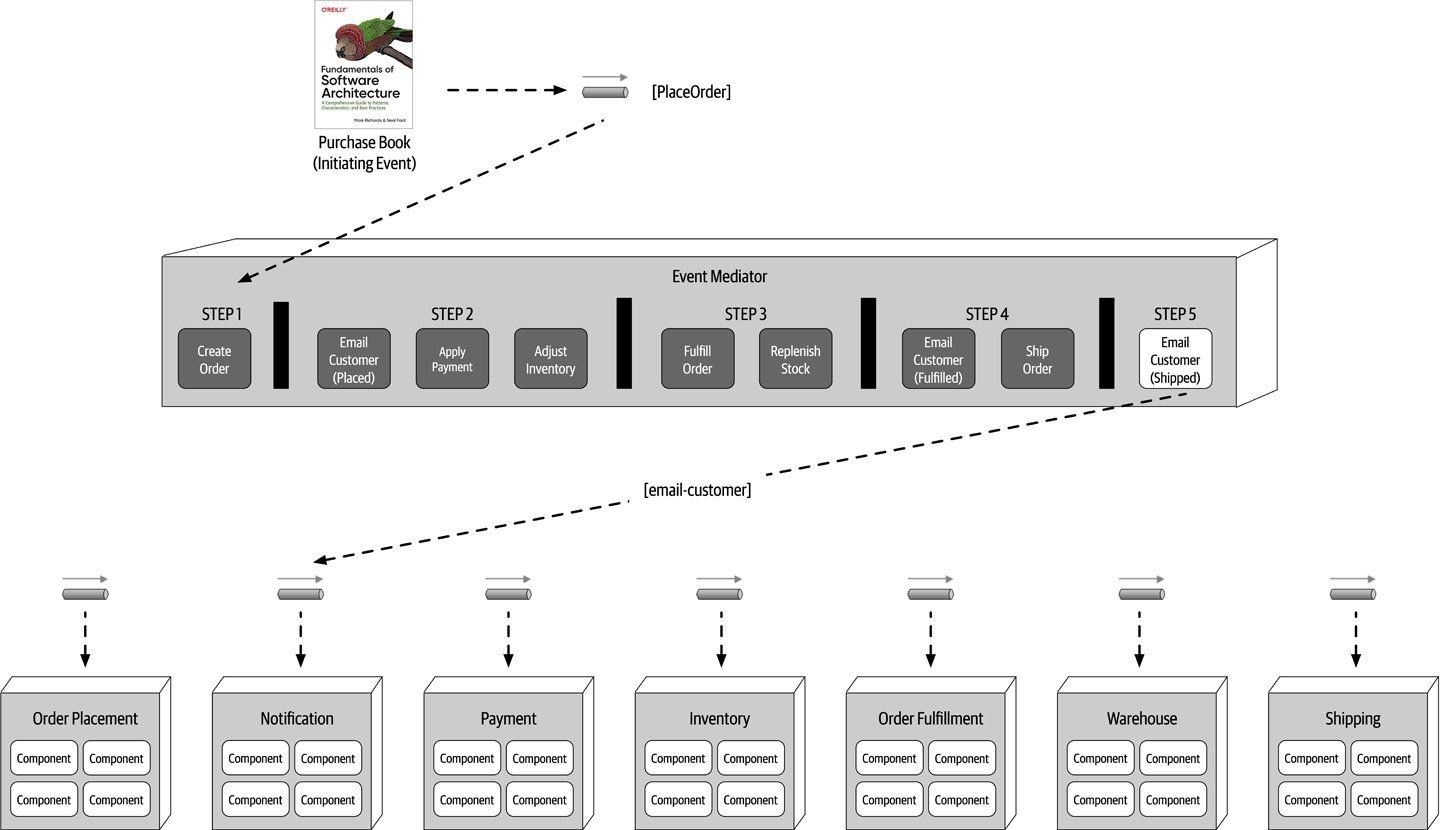

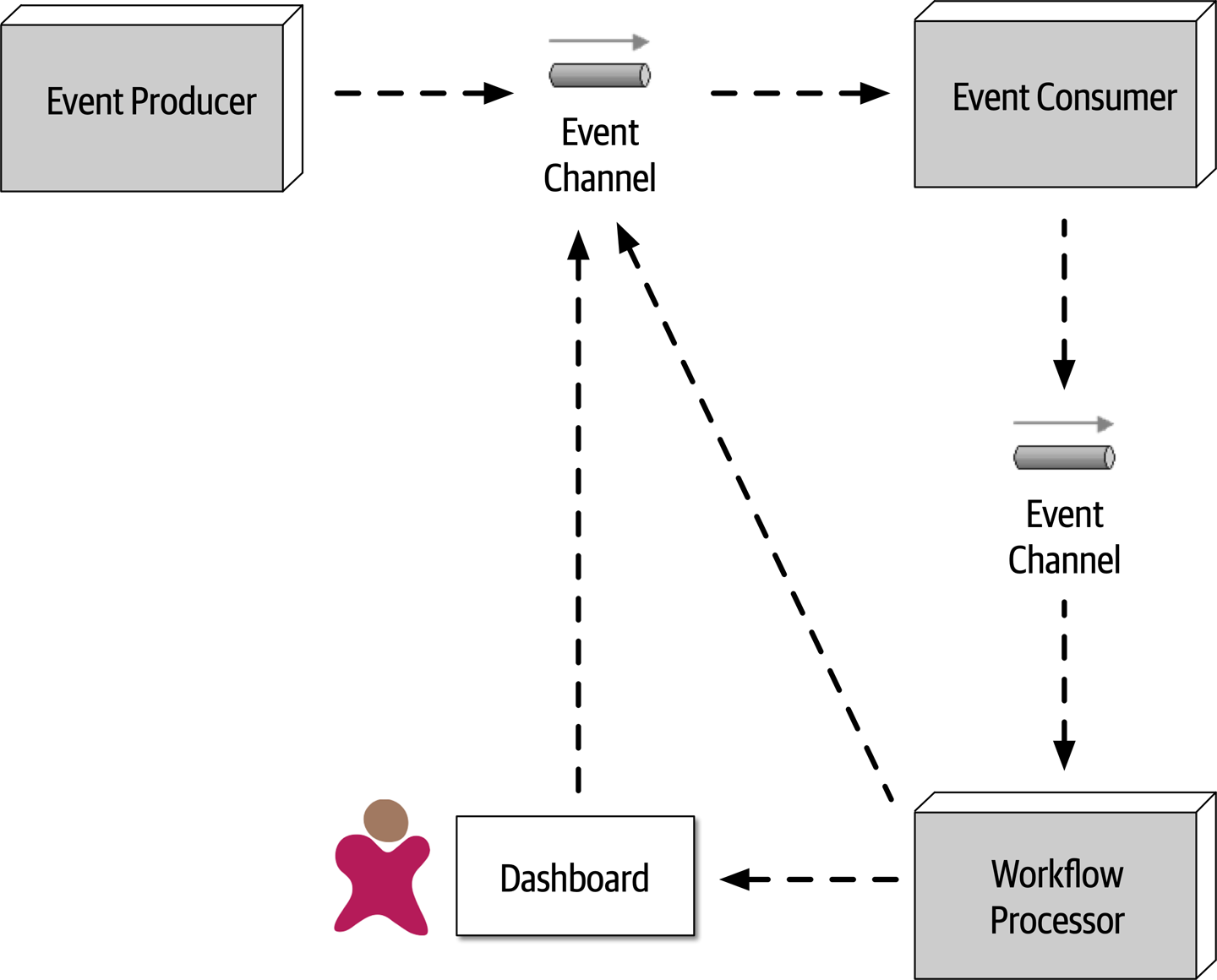

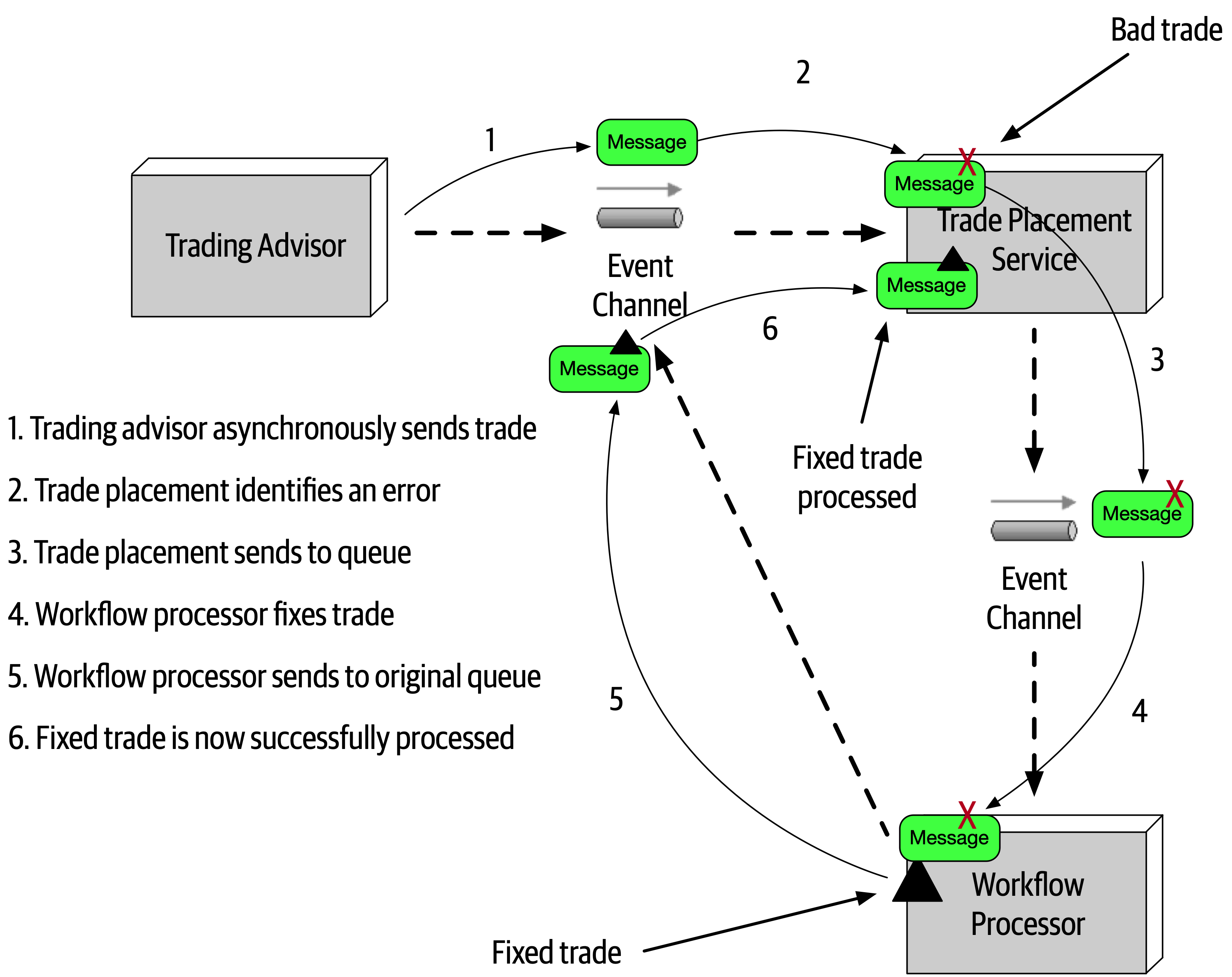

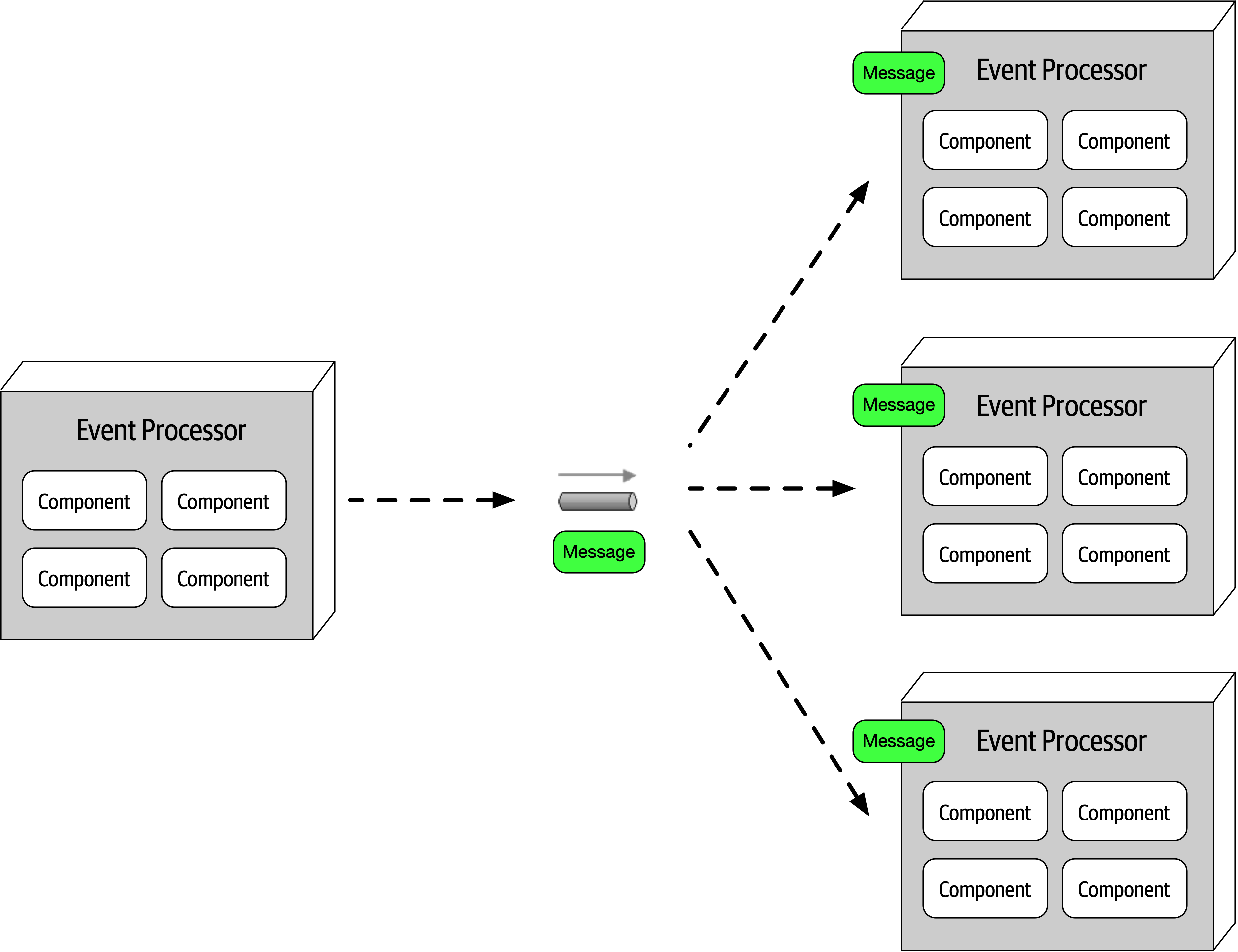

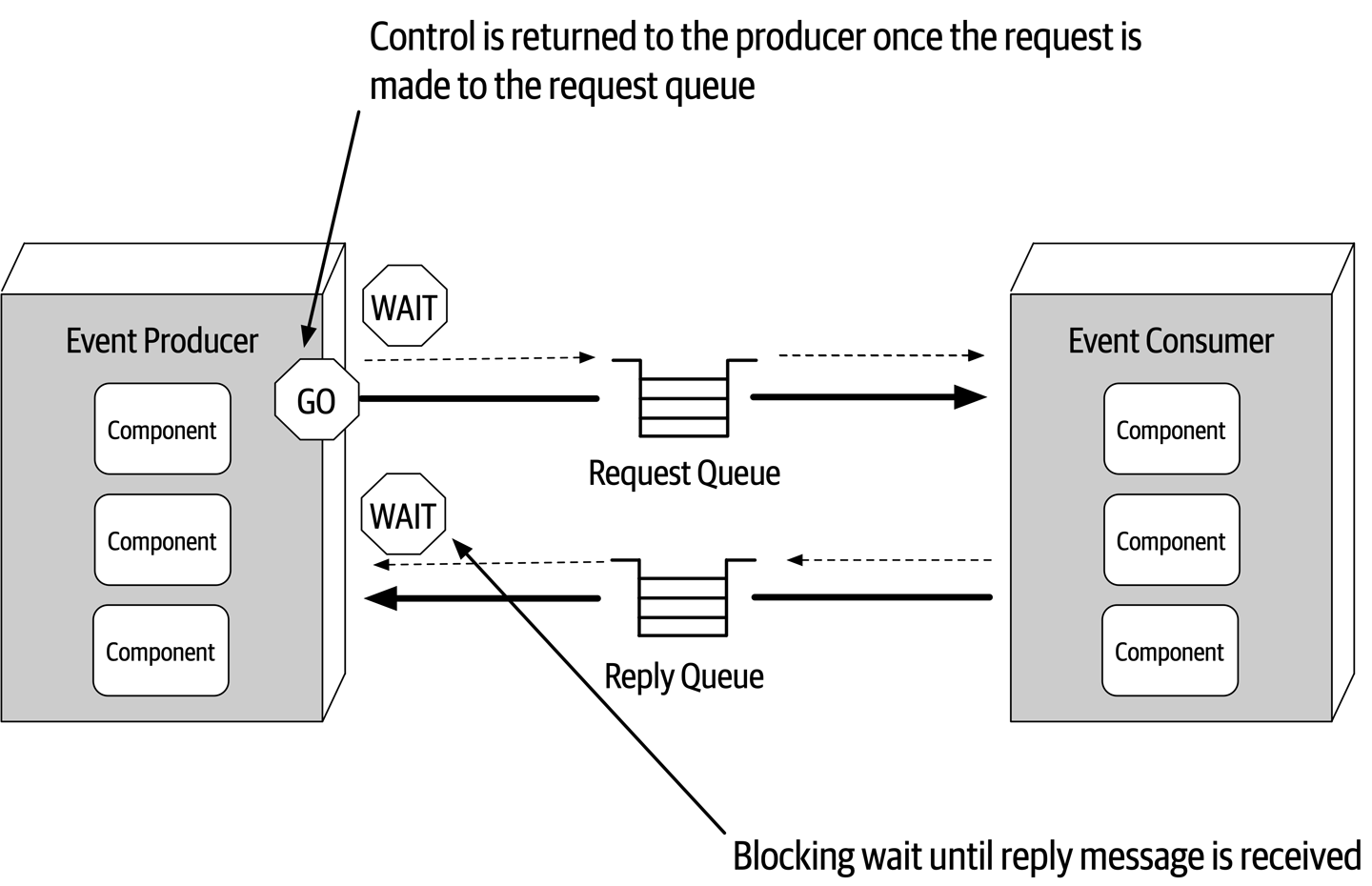

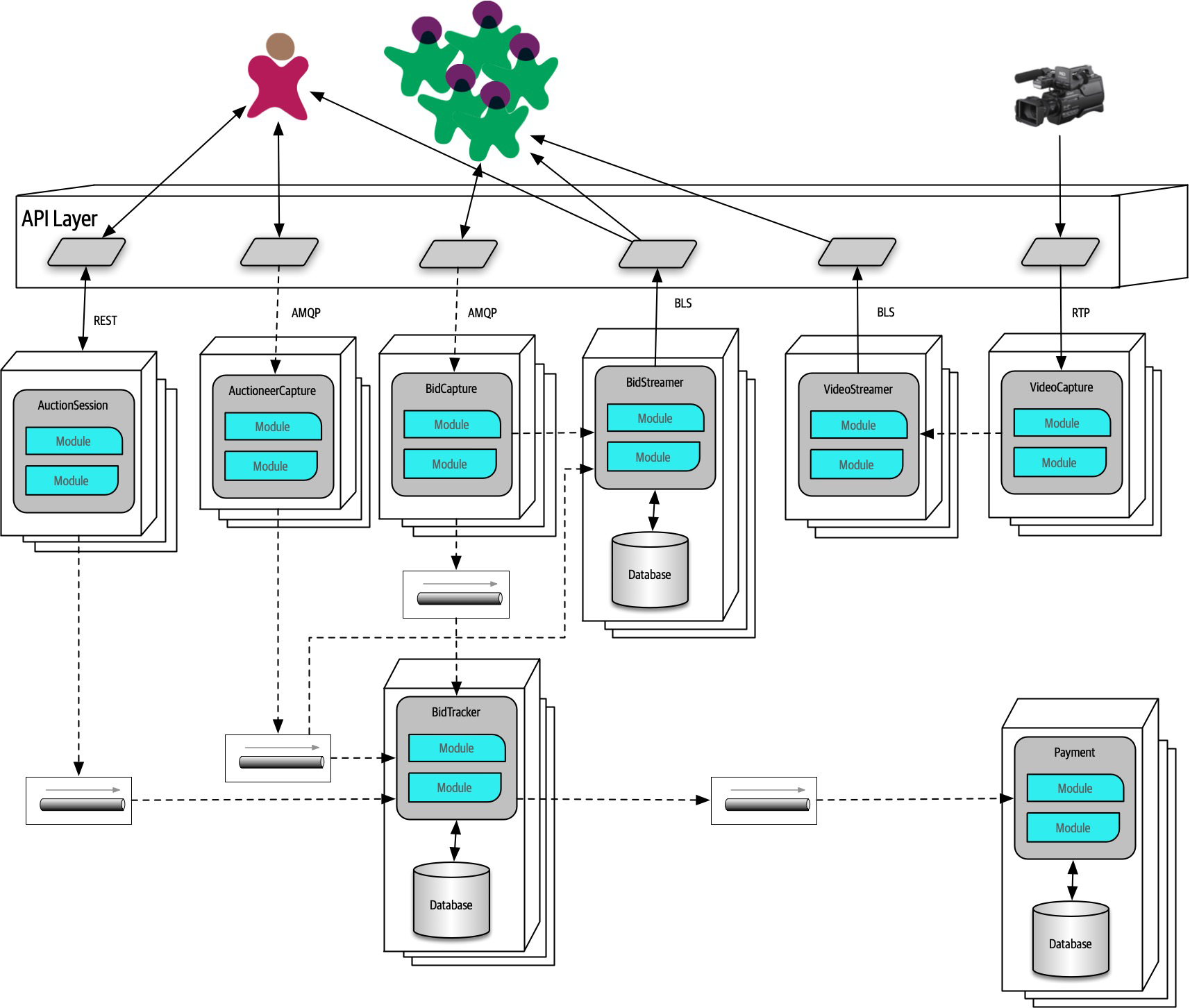

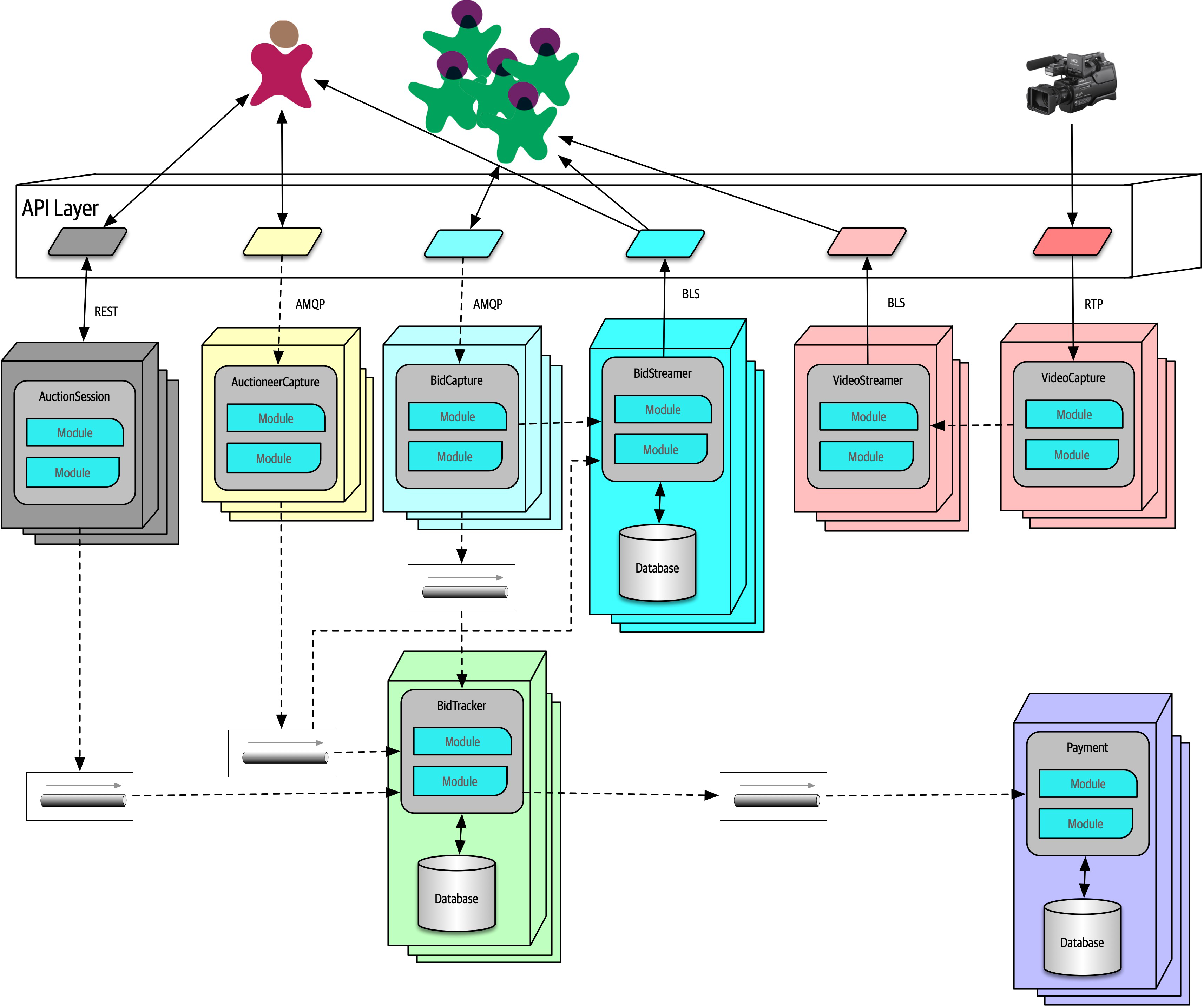

- 14. Event-Driven Architecture Style

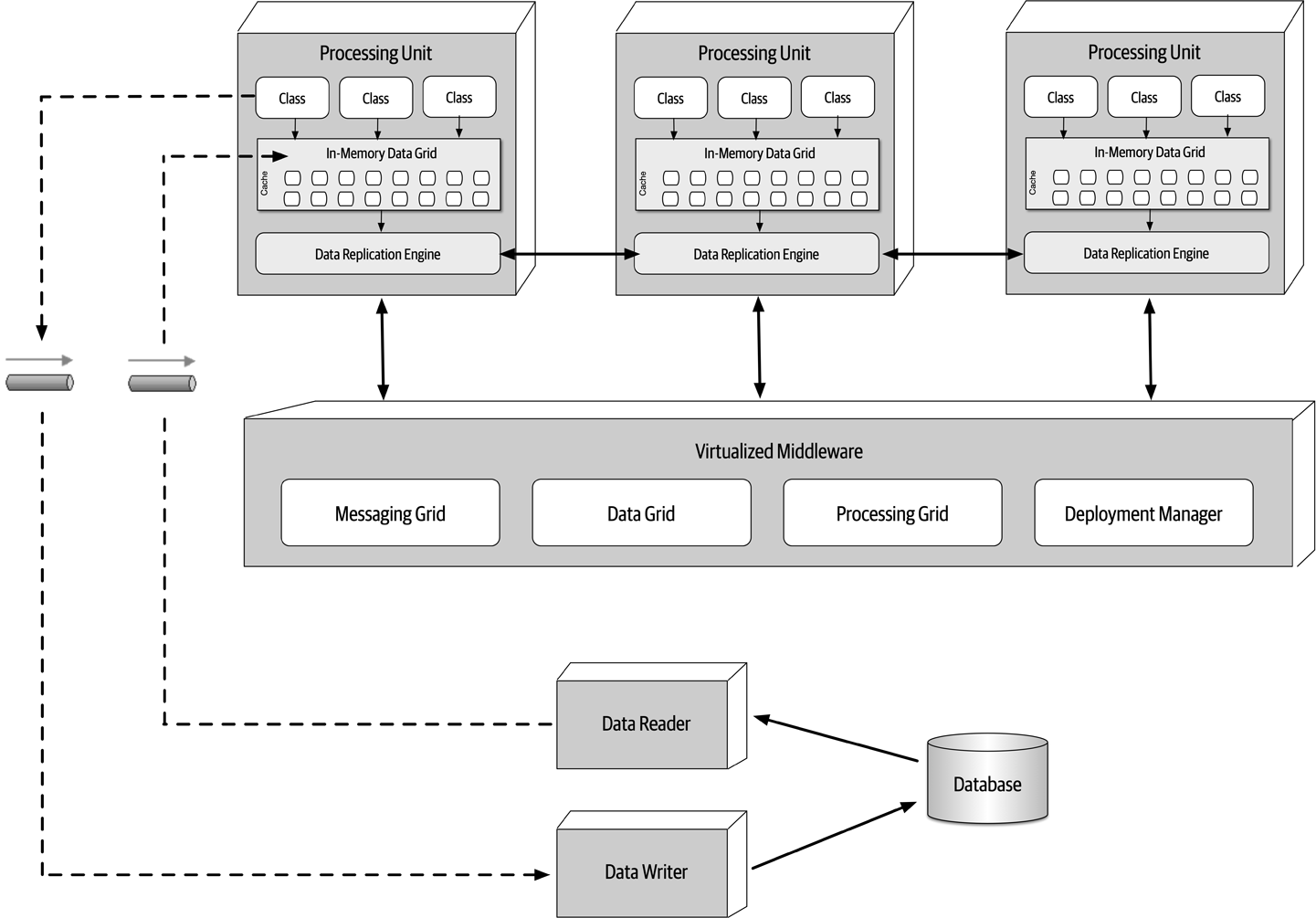

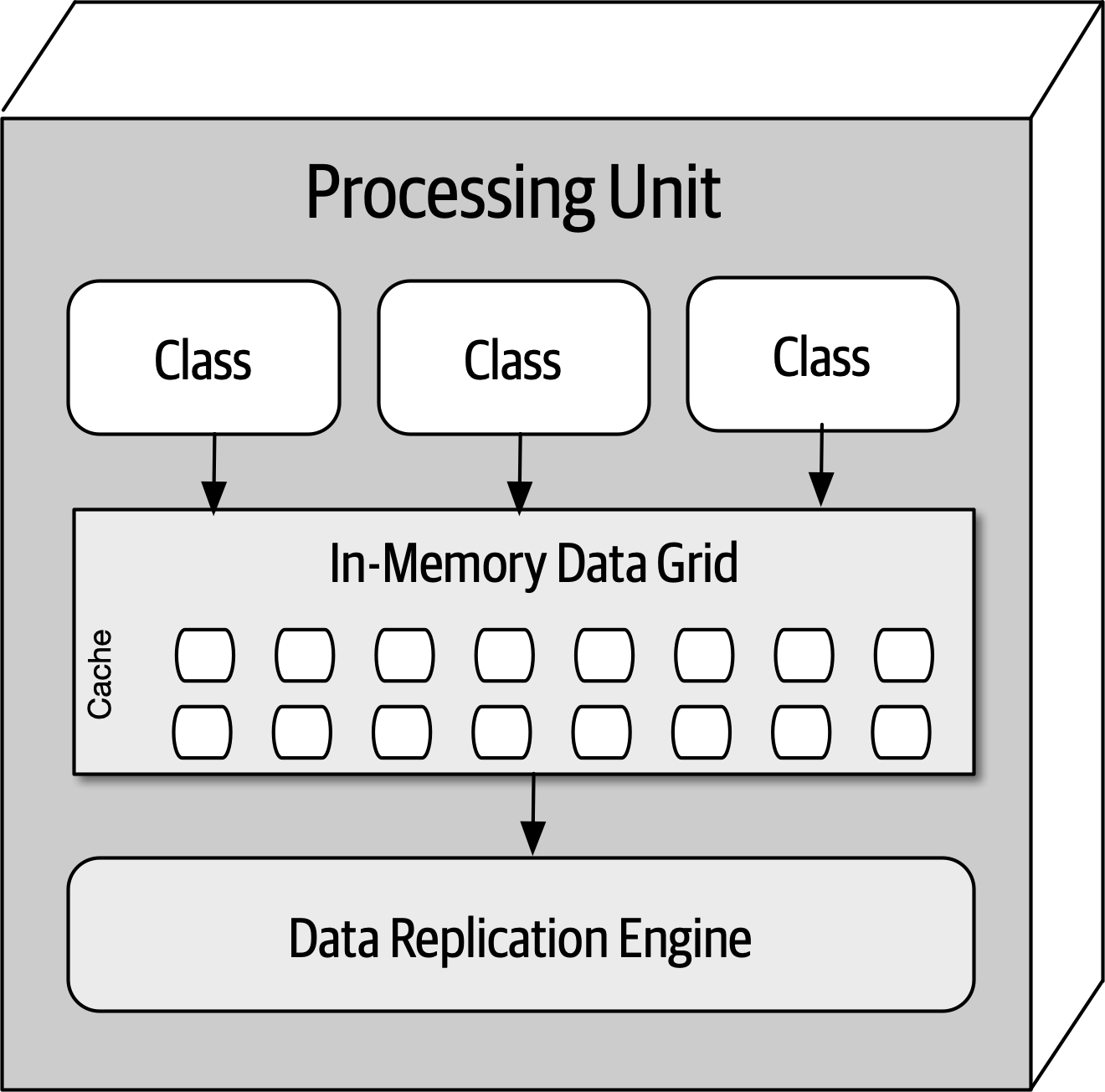

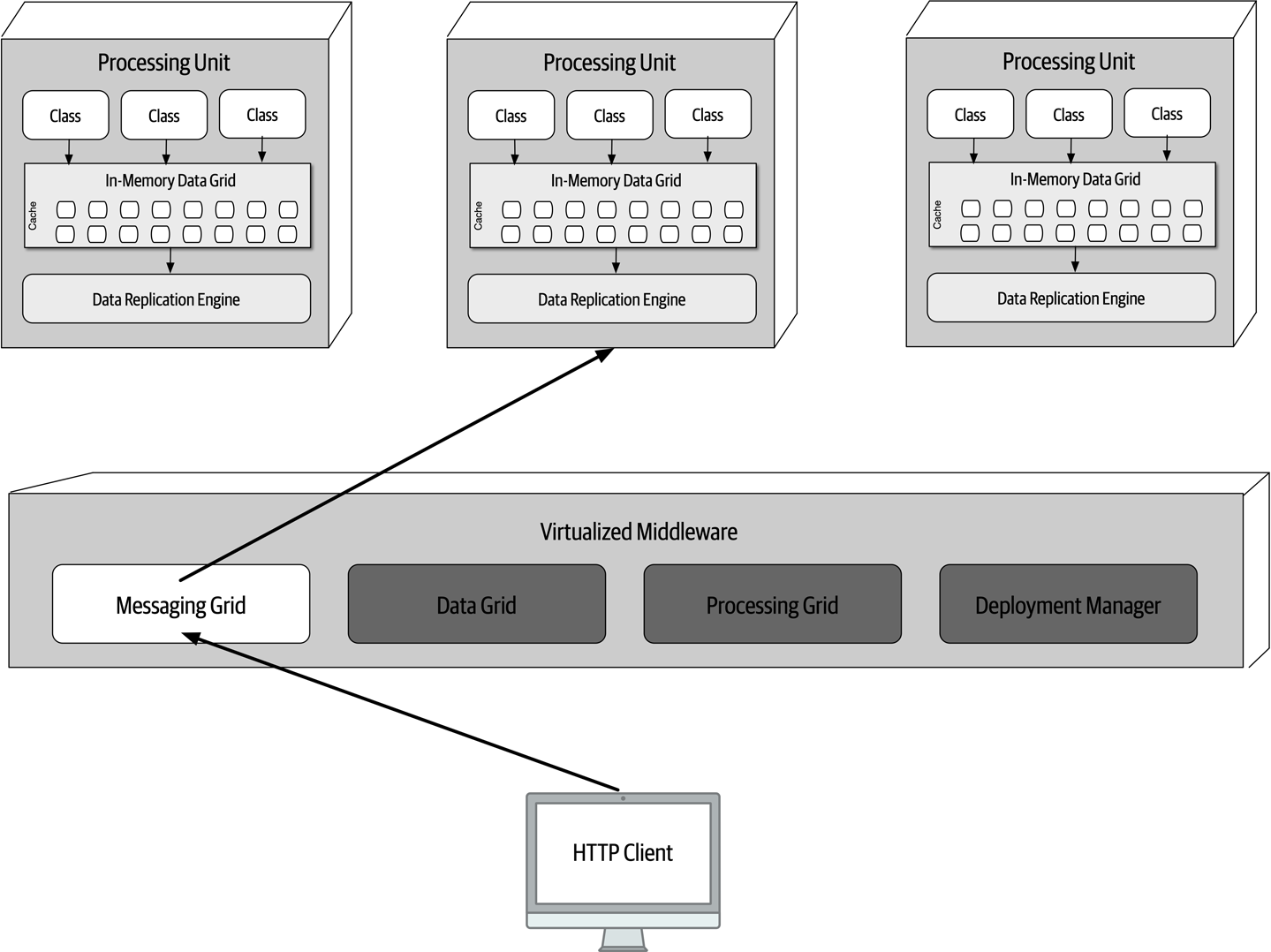

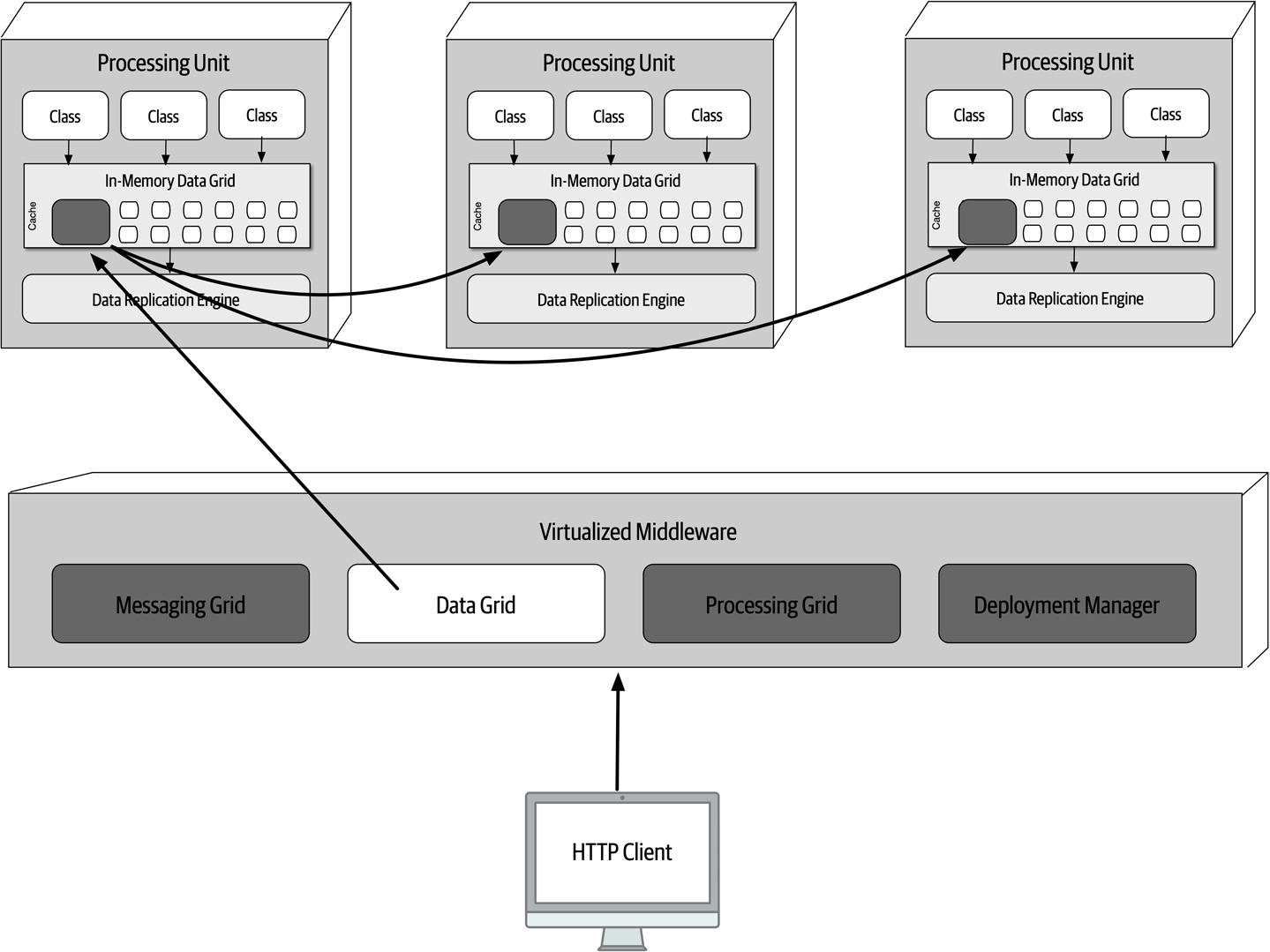

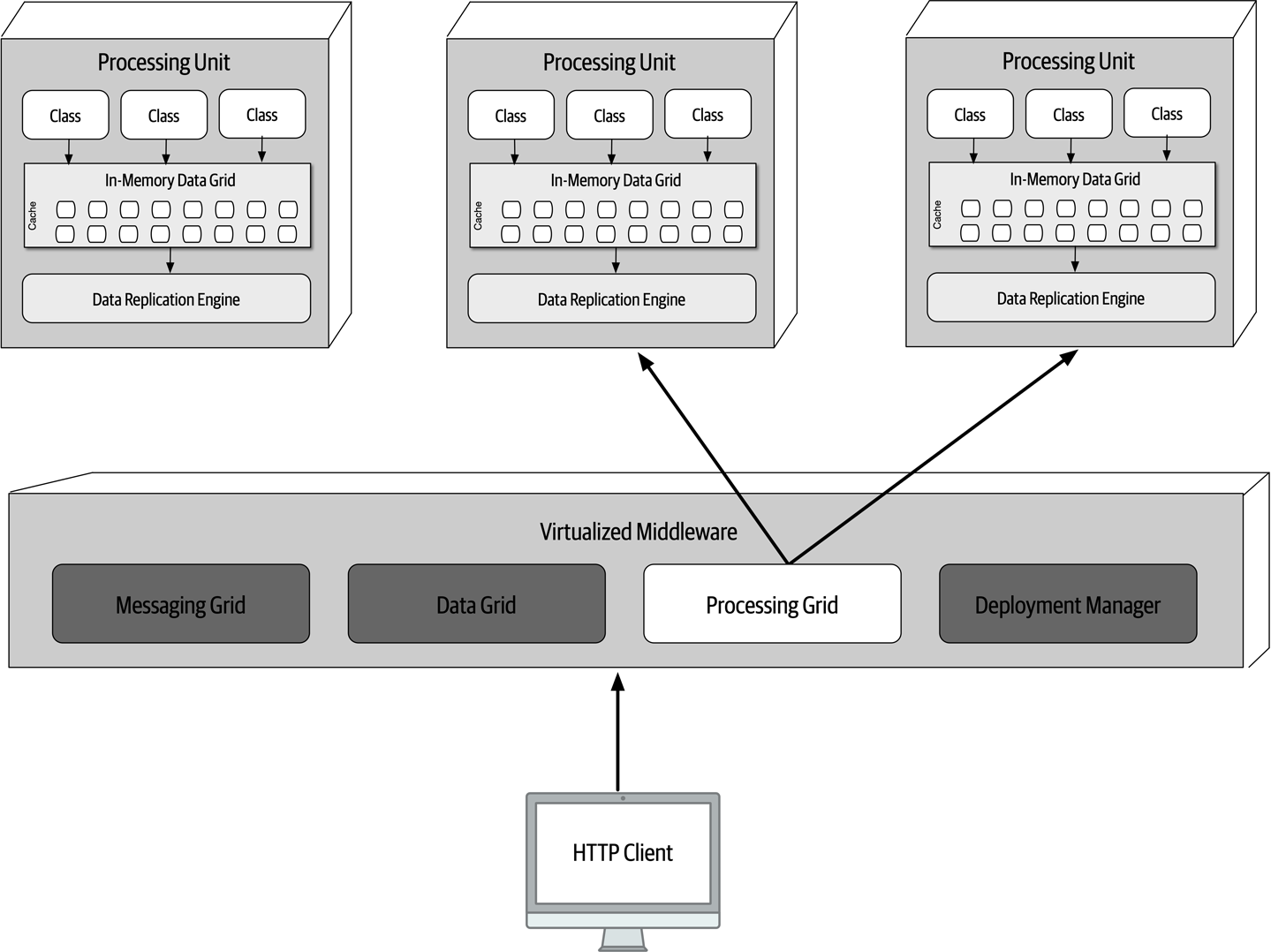

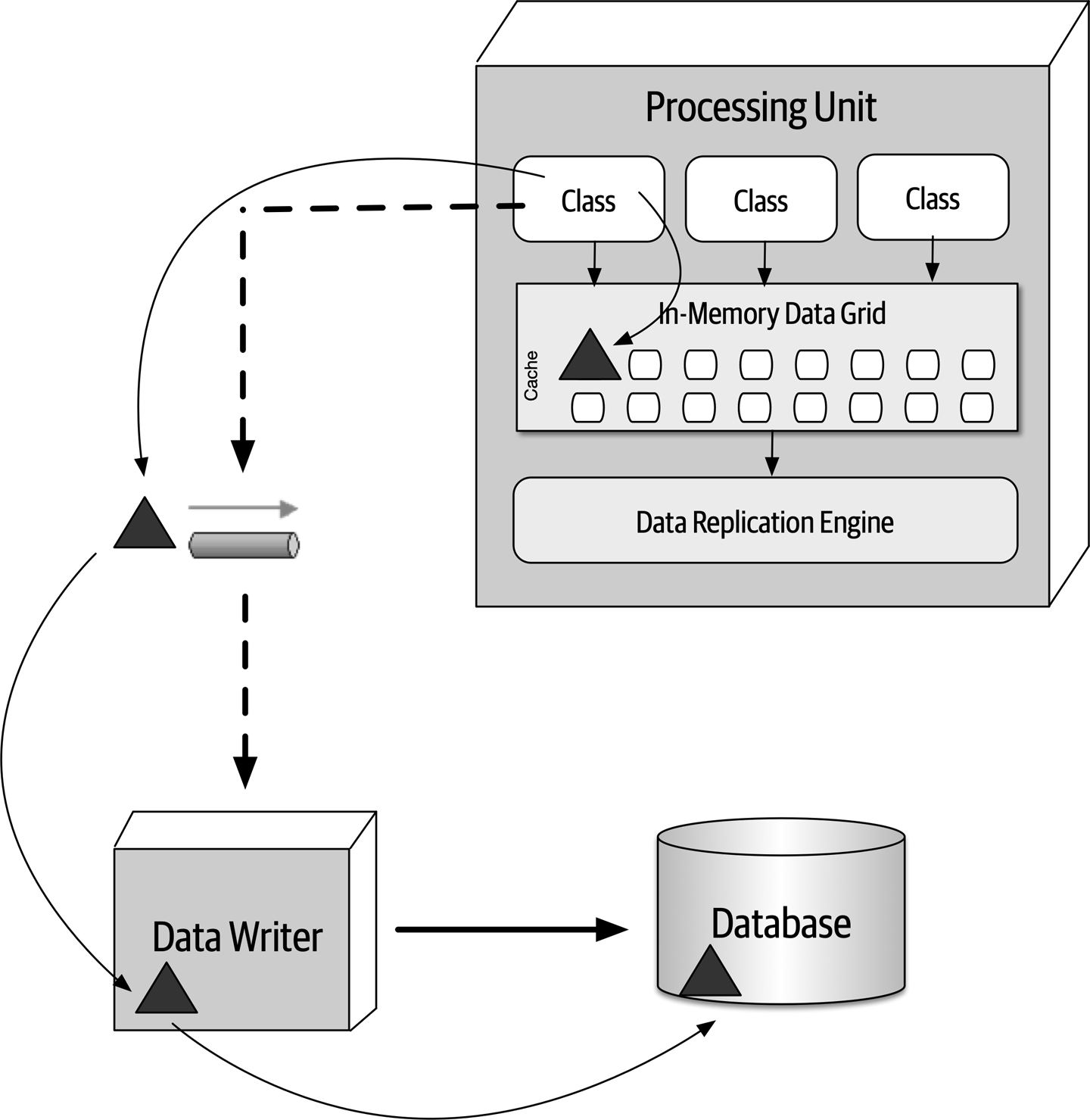

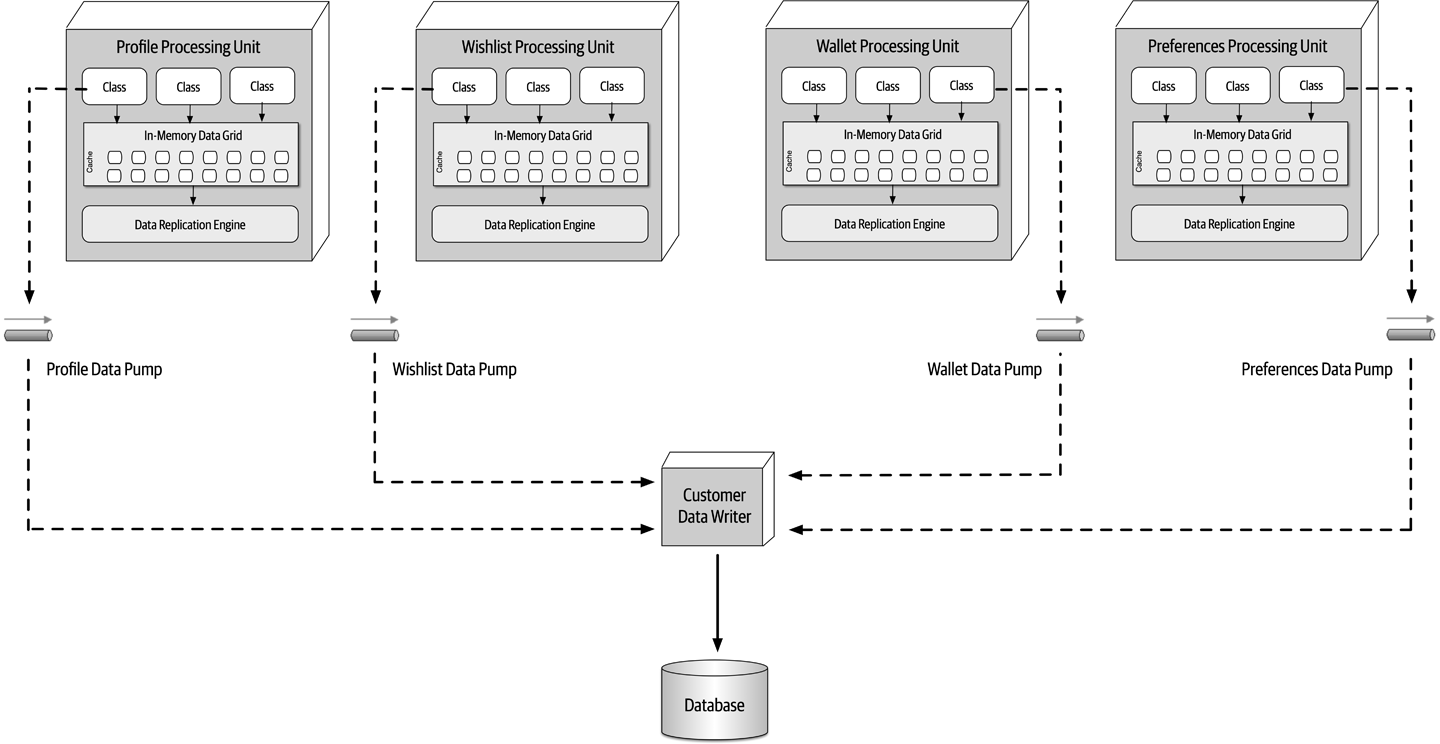

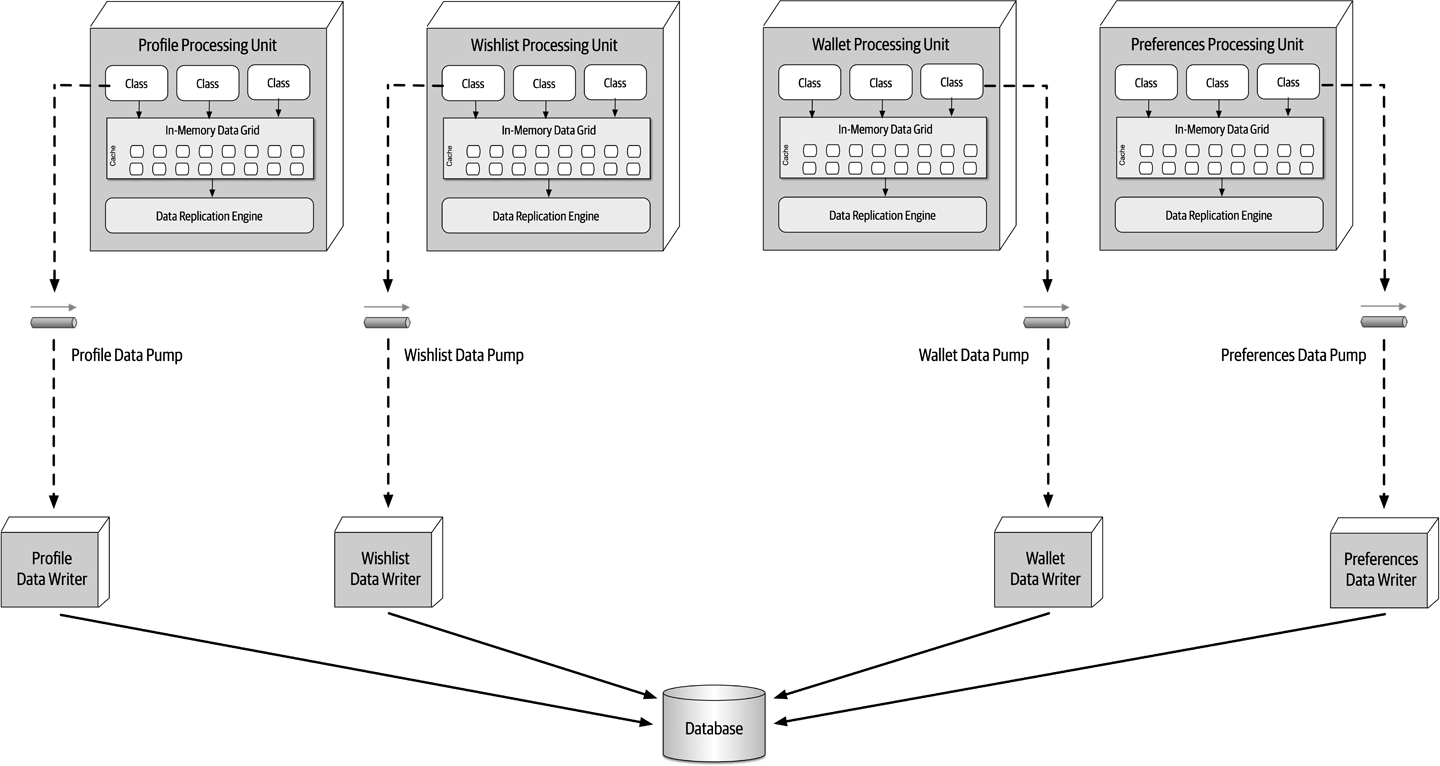

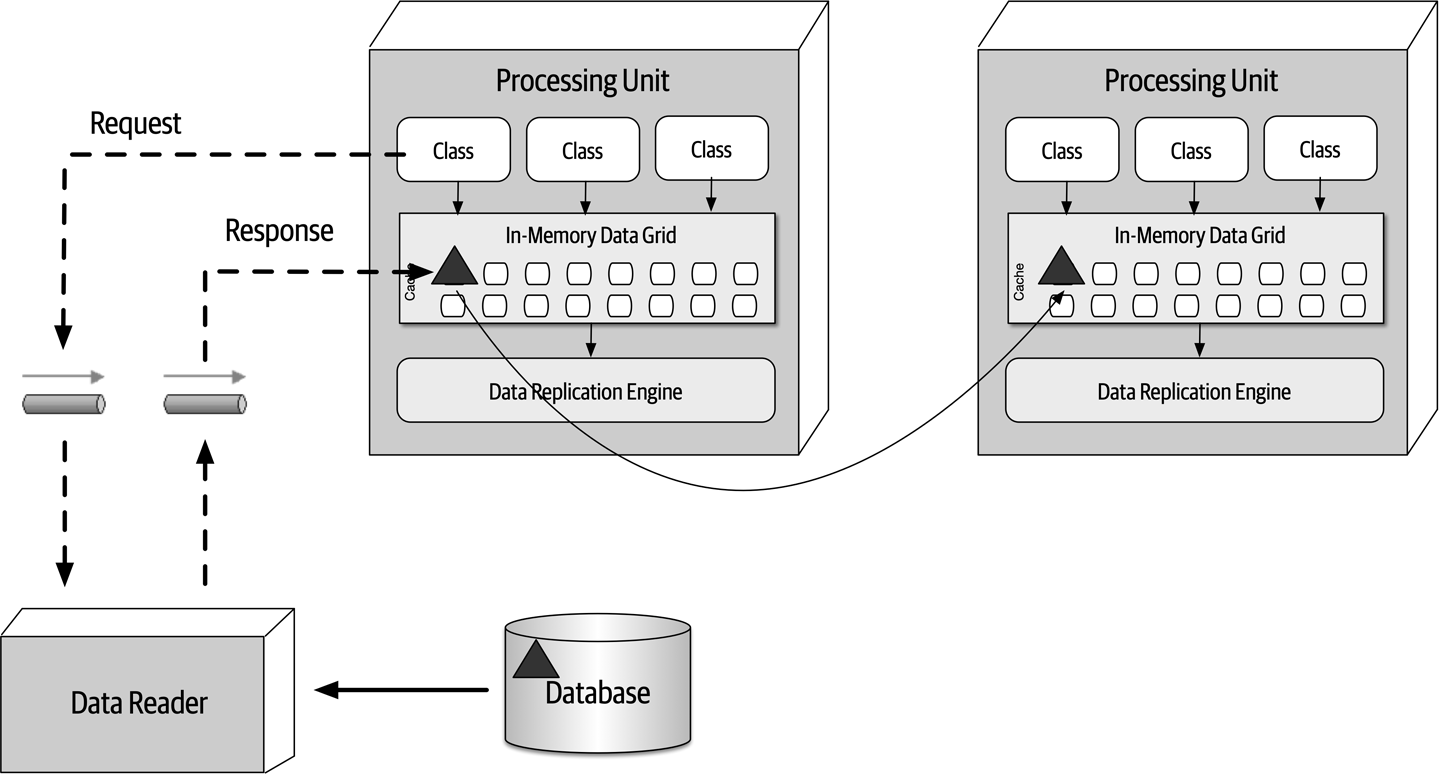

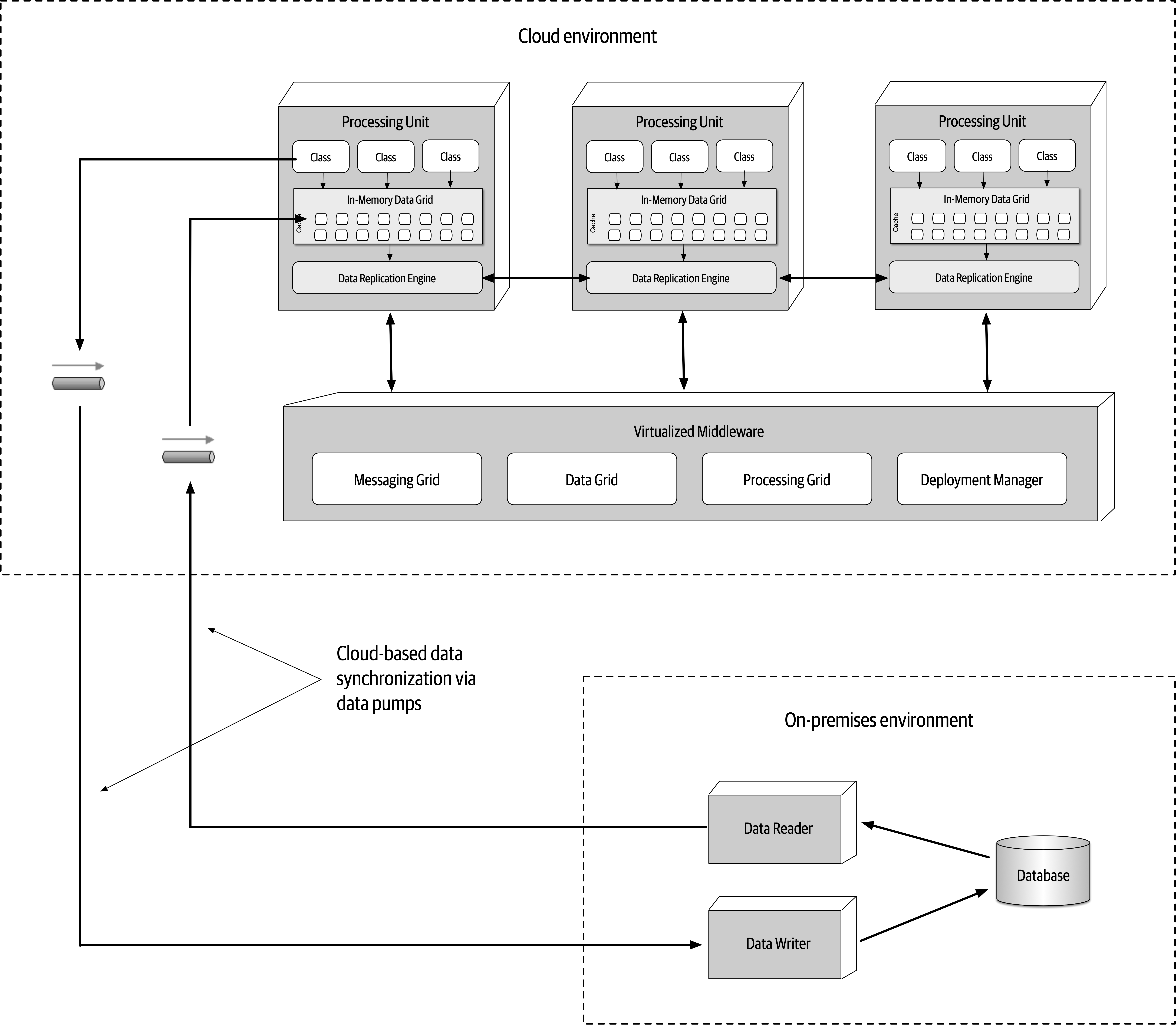

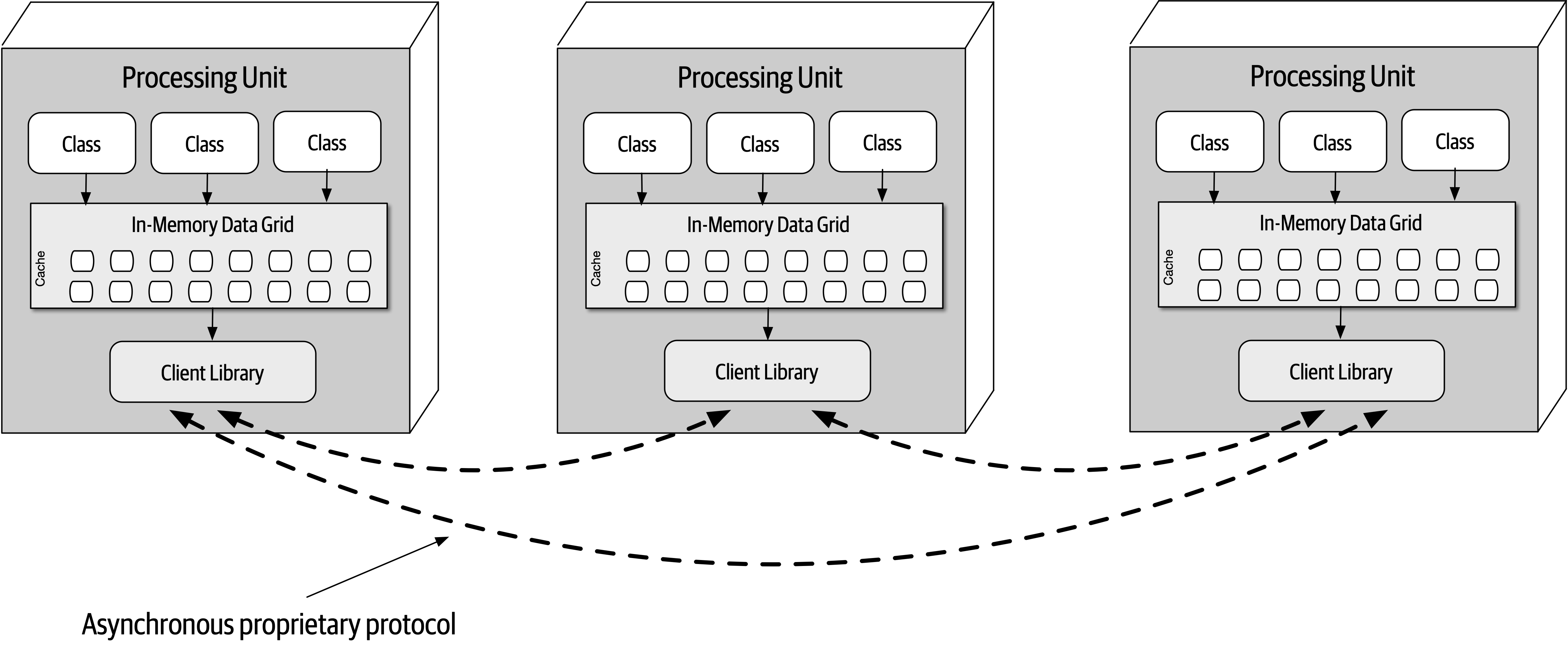

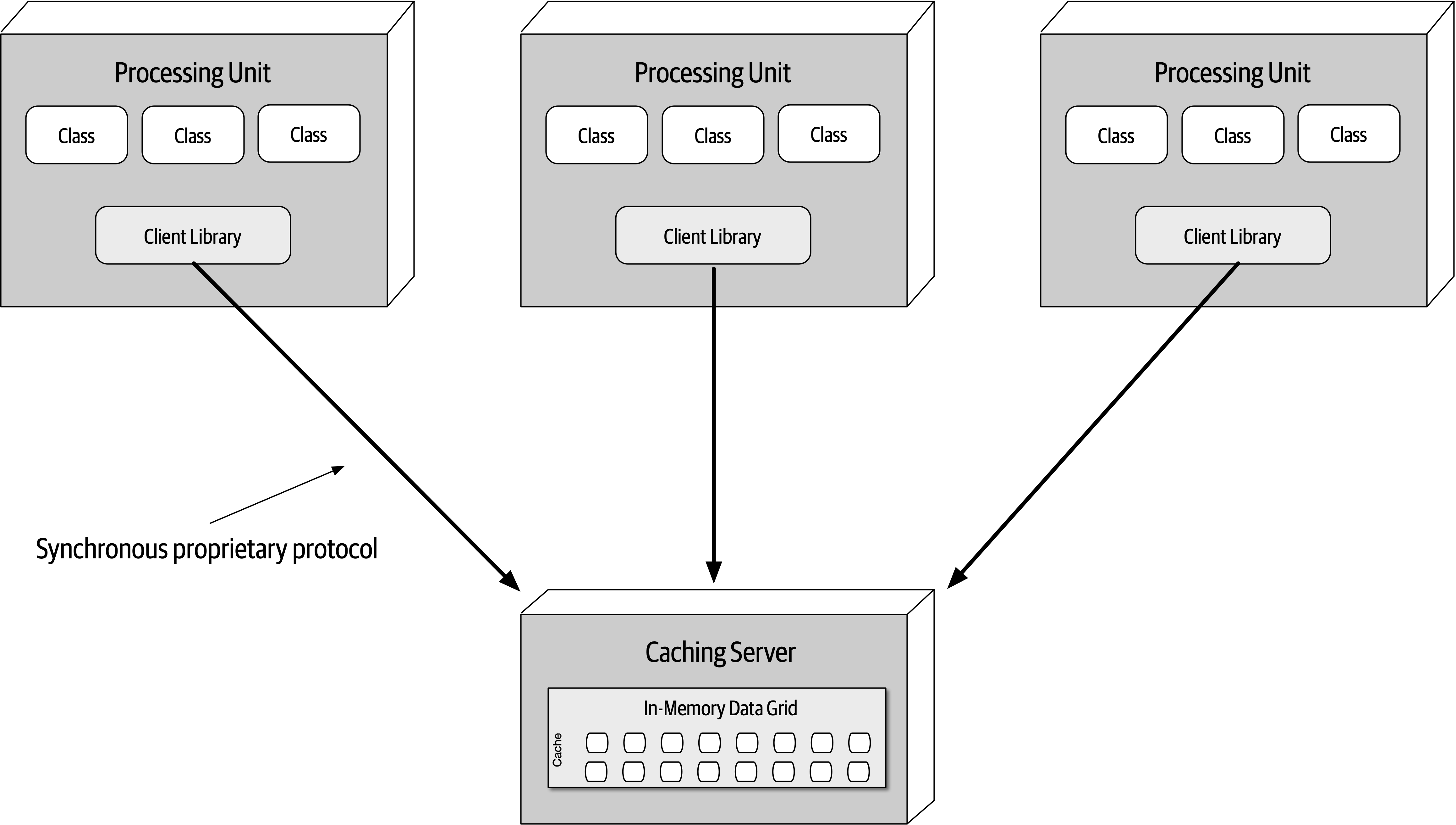

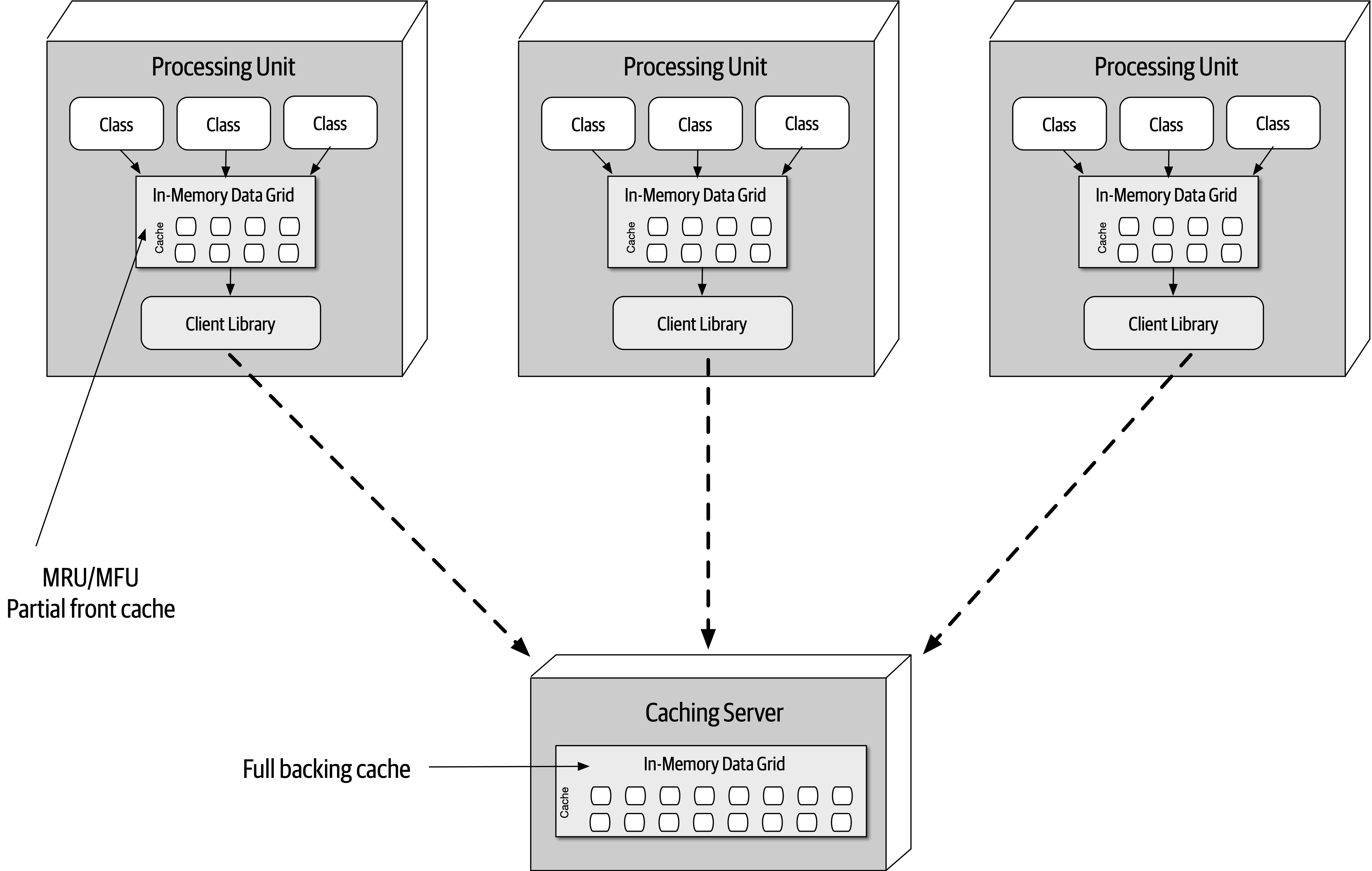

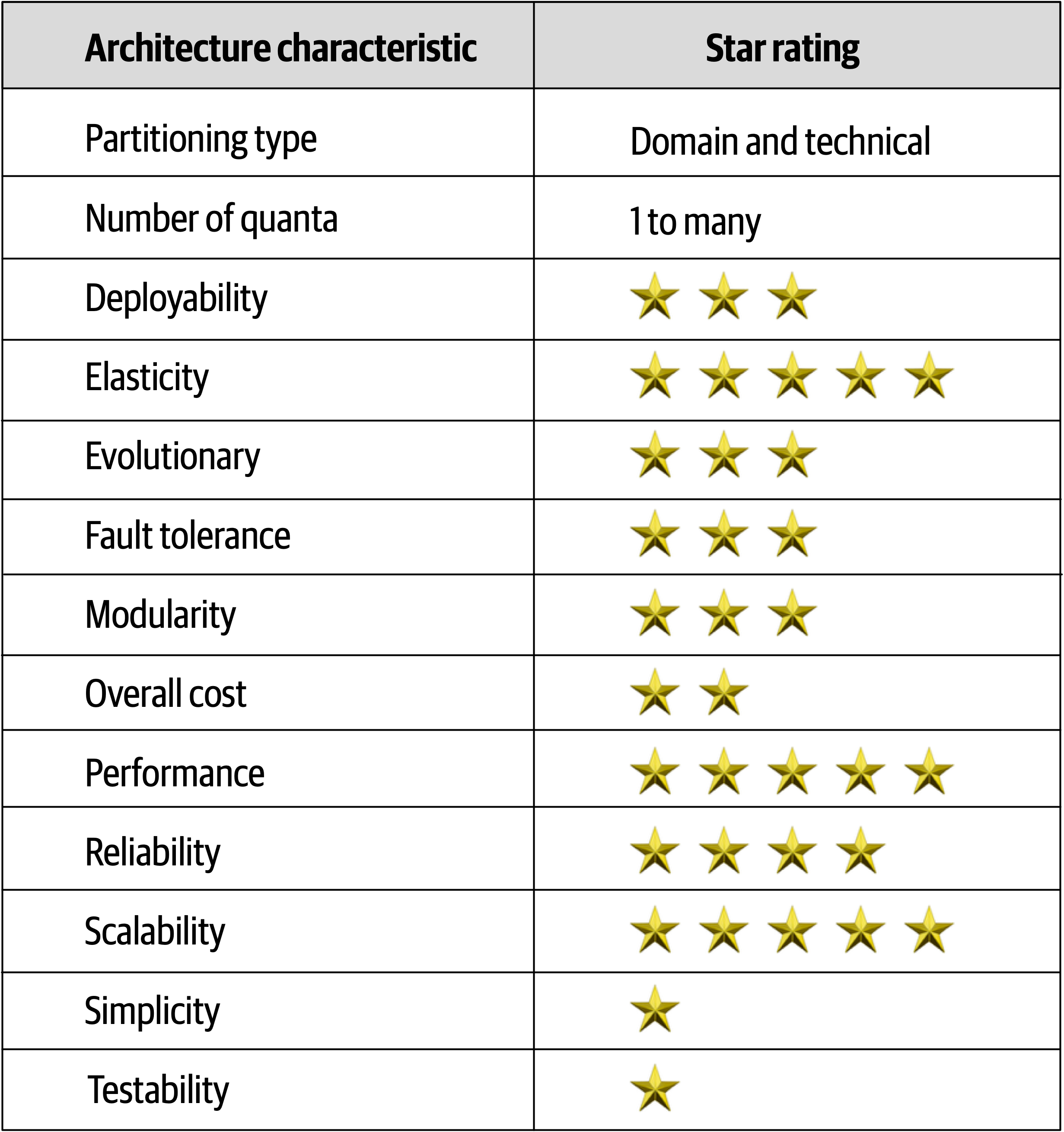

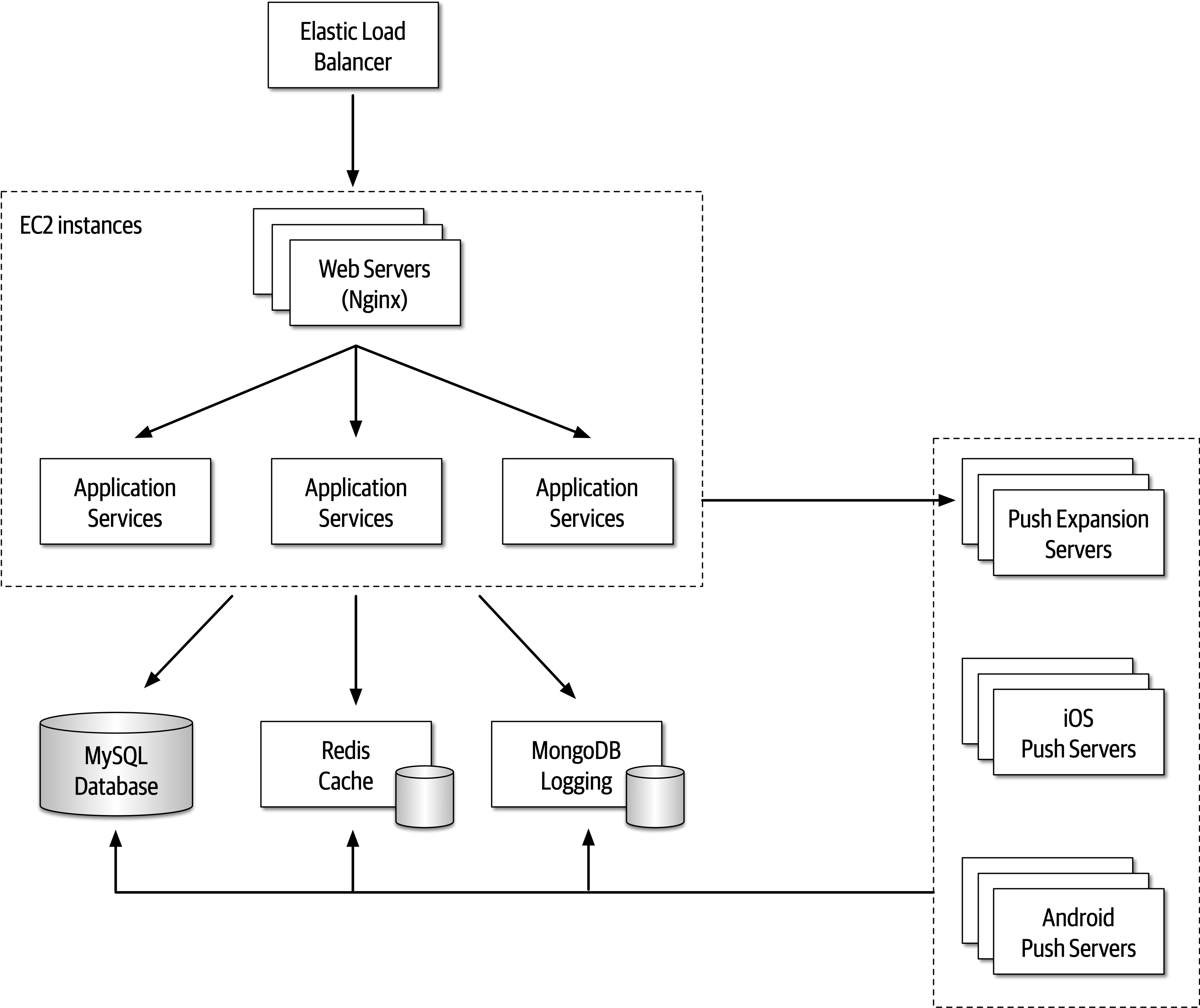

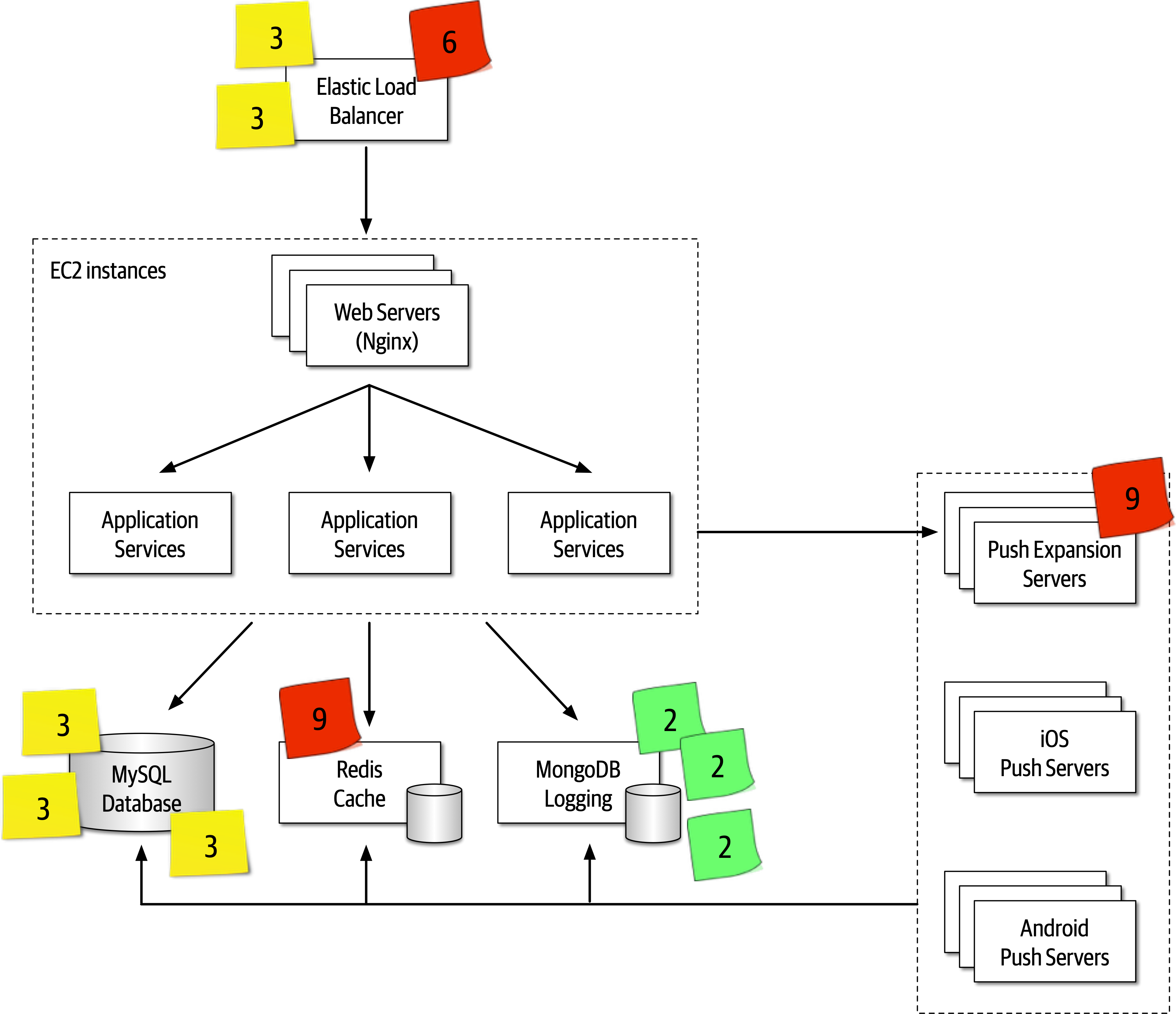

- 15. Space-Based Architecture Style

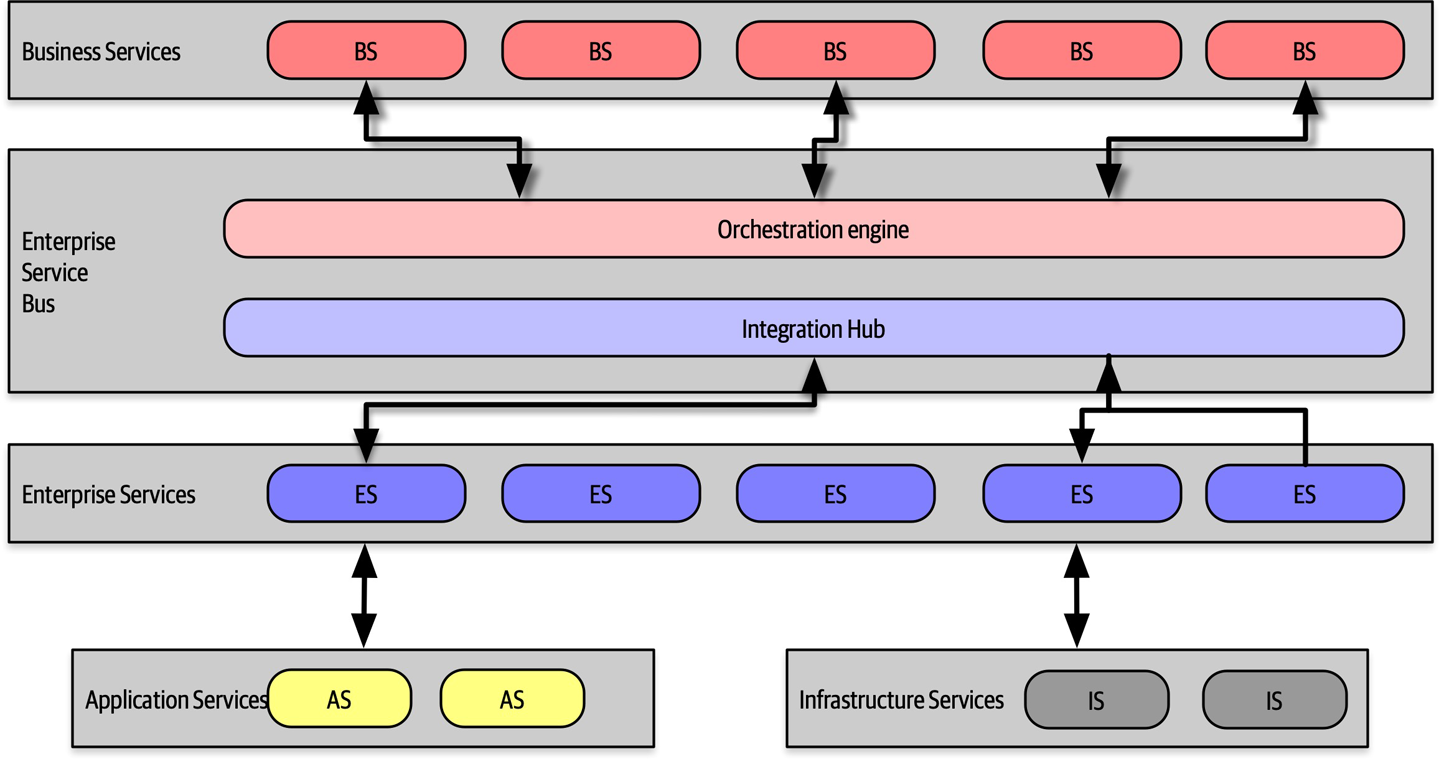

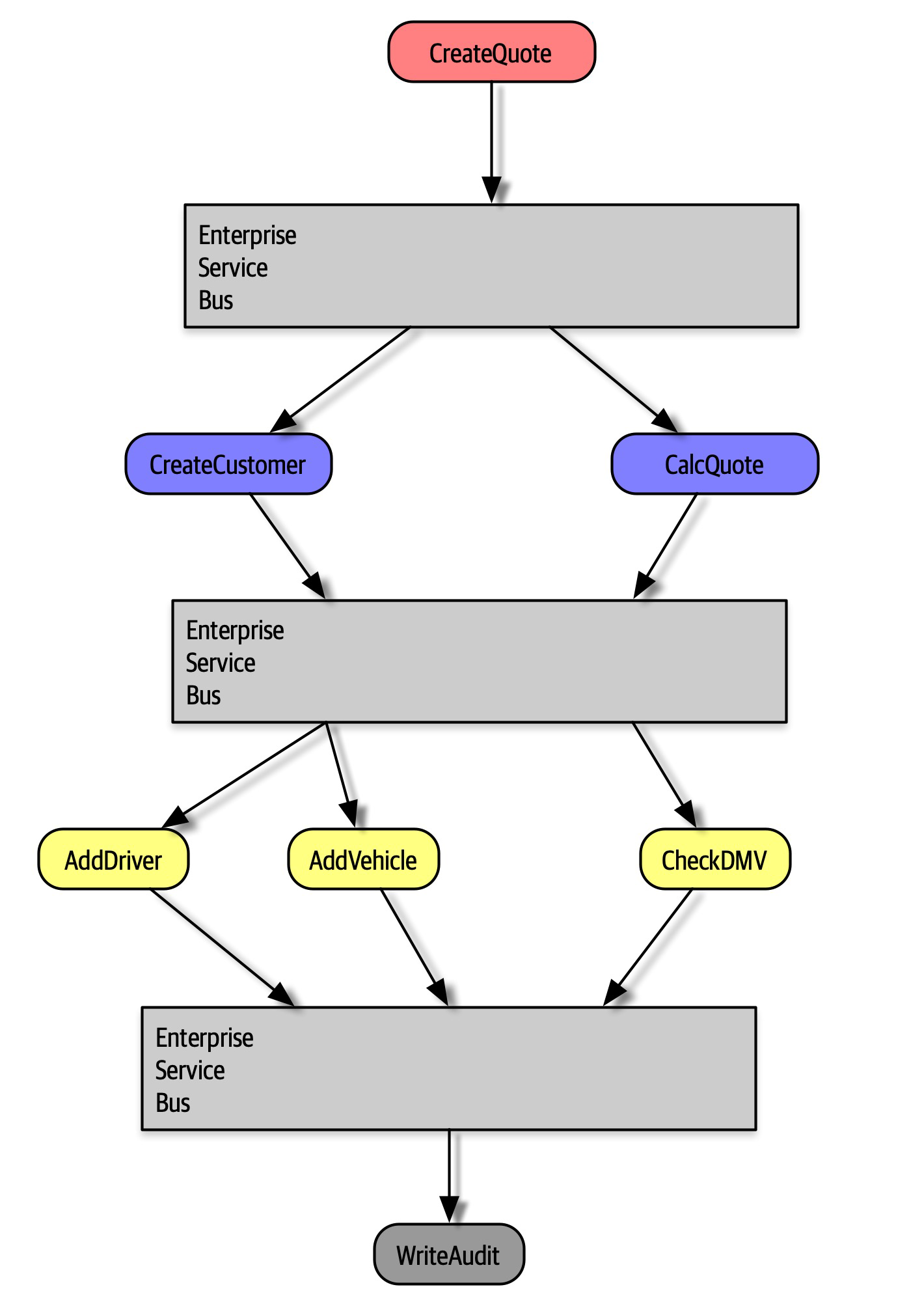

- 16. Orchestration-Driven Service-Oriented Architecture

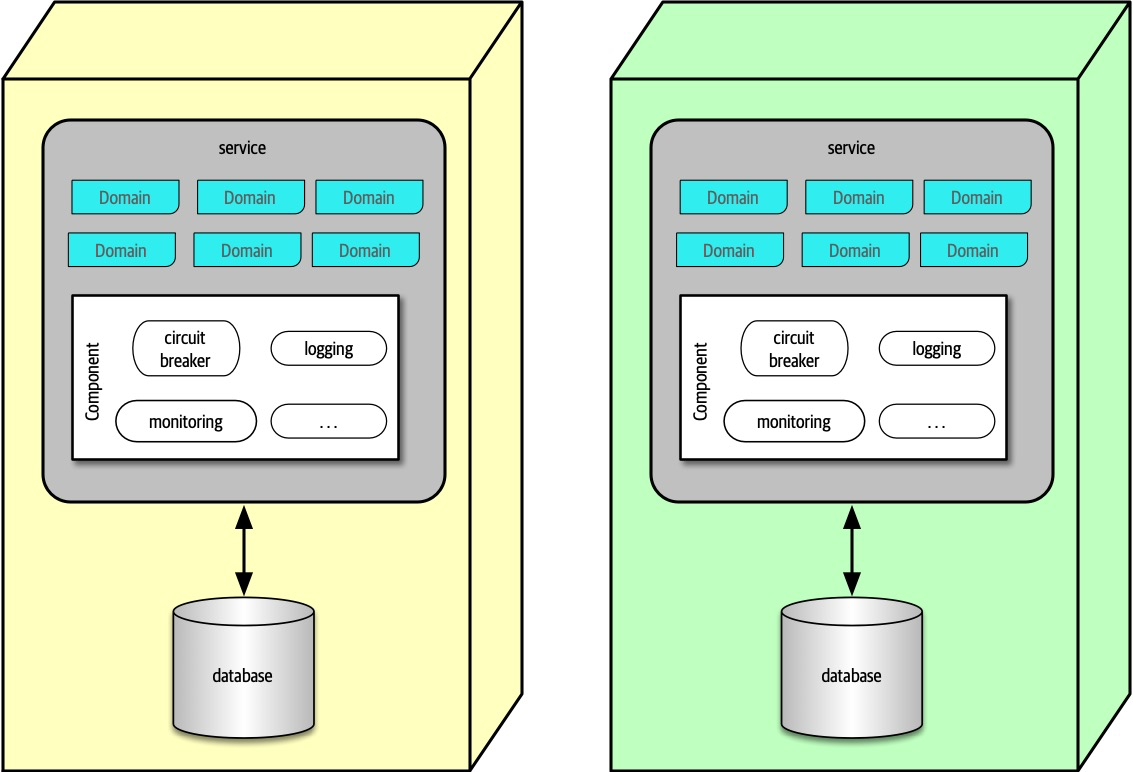

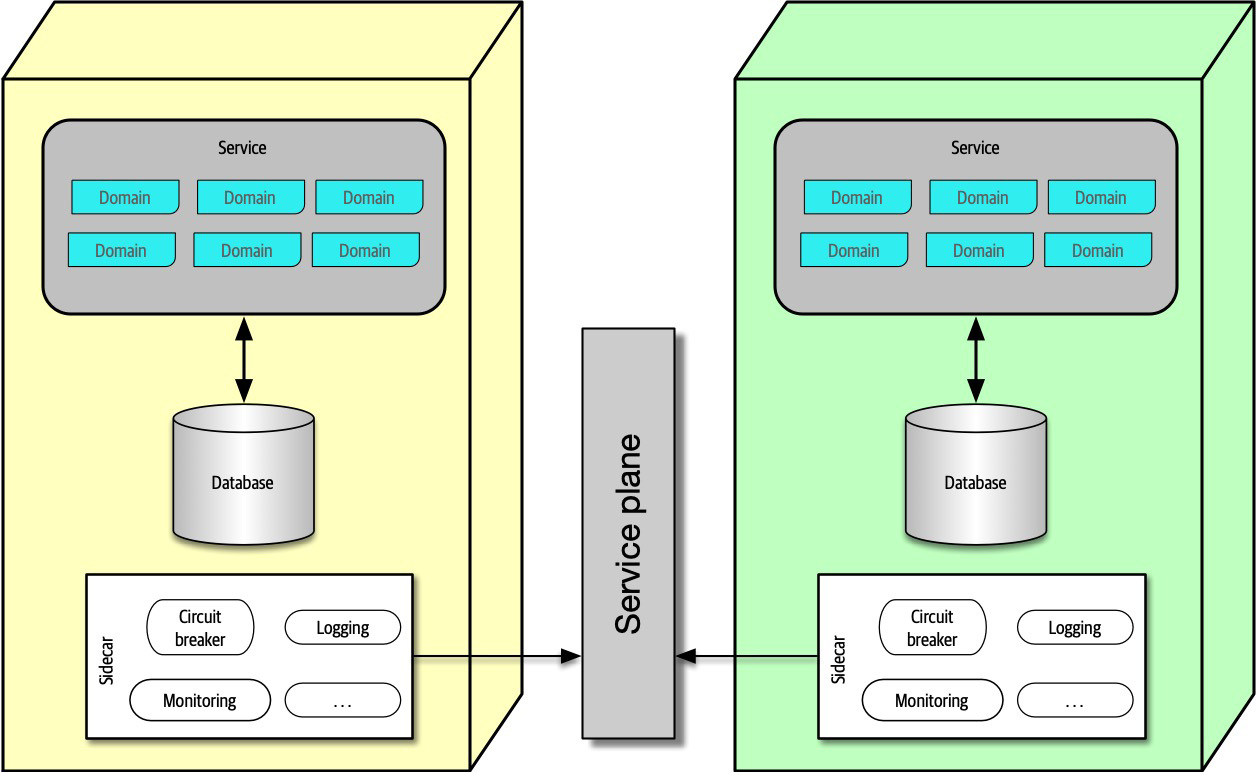

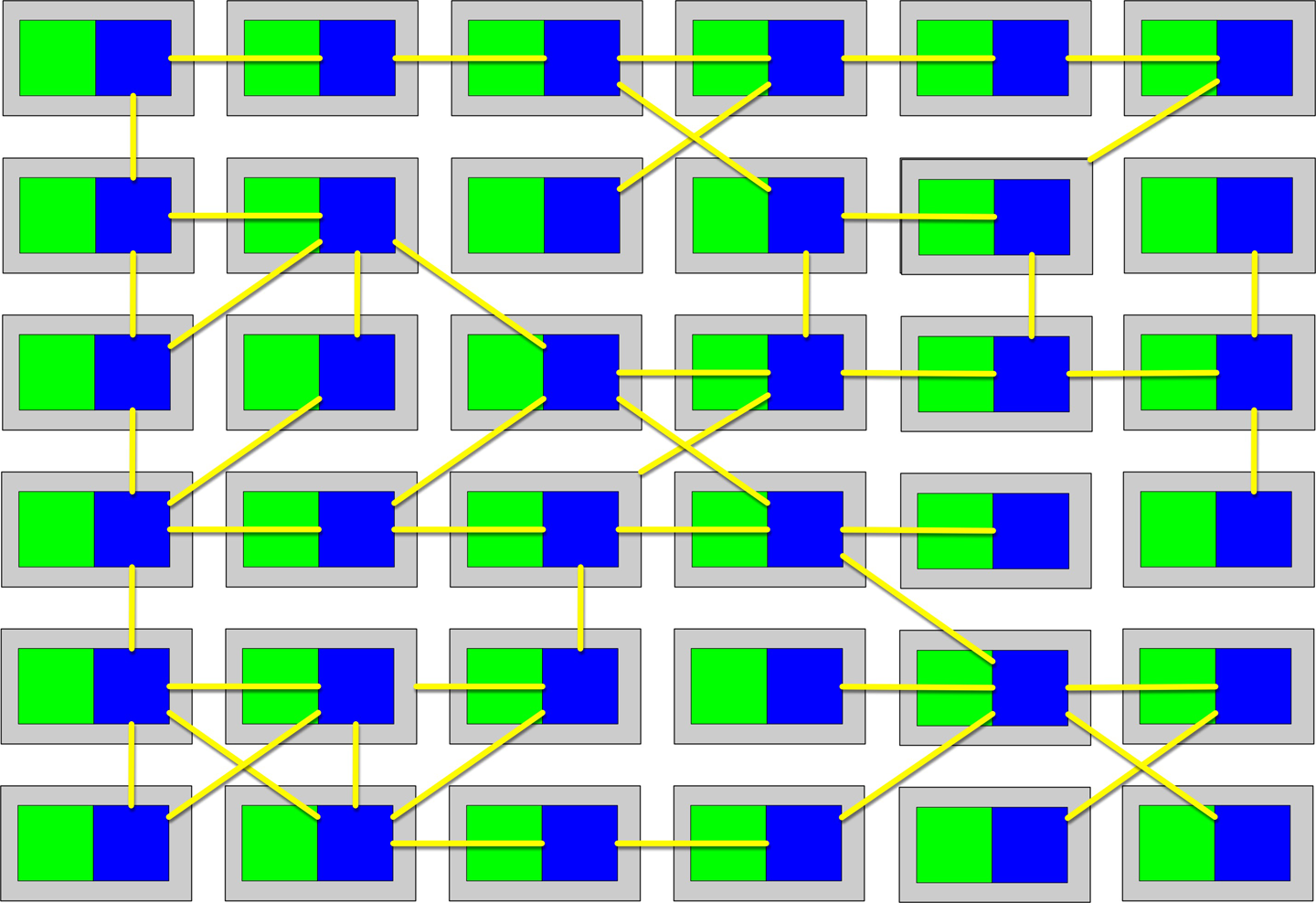

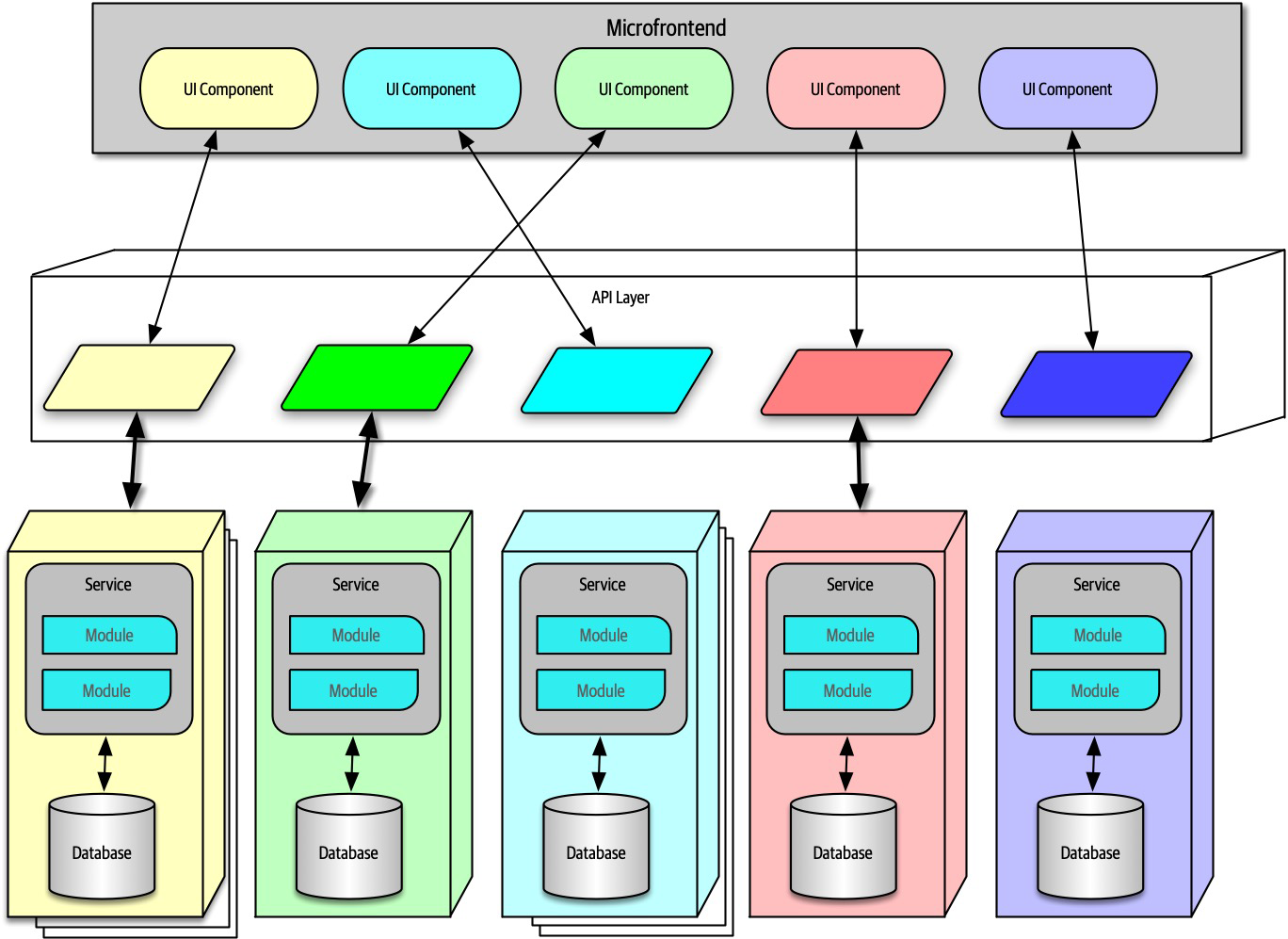

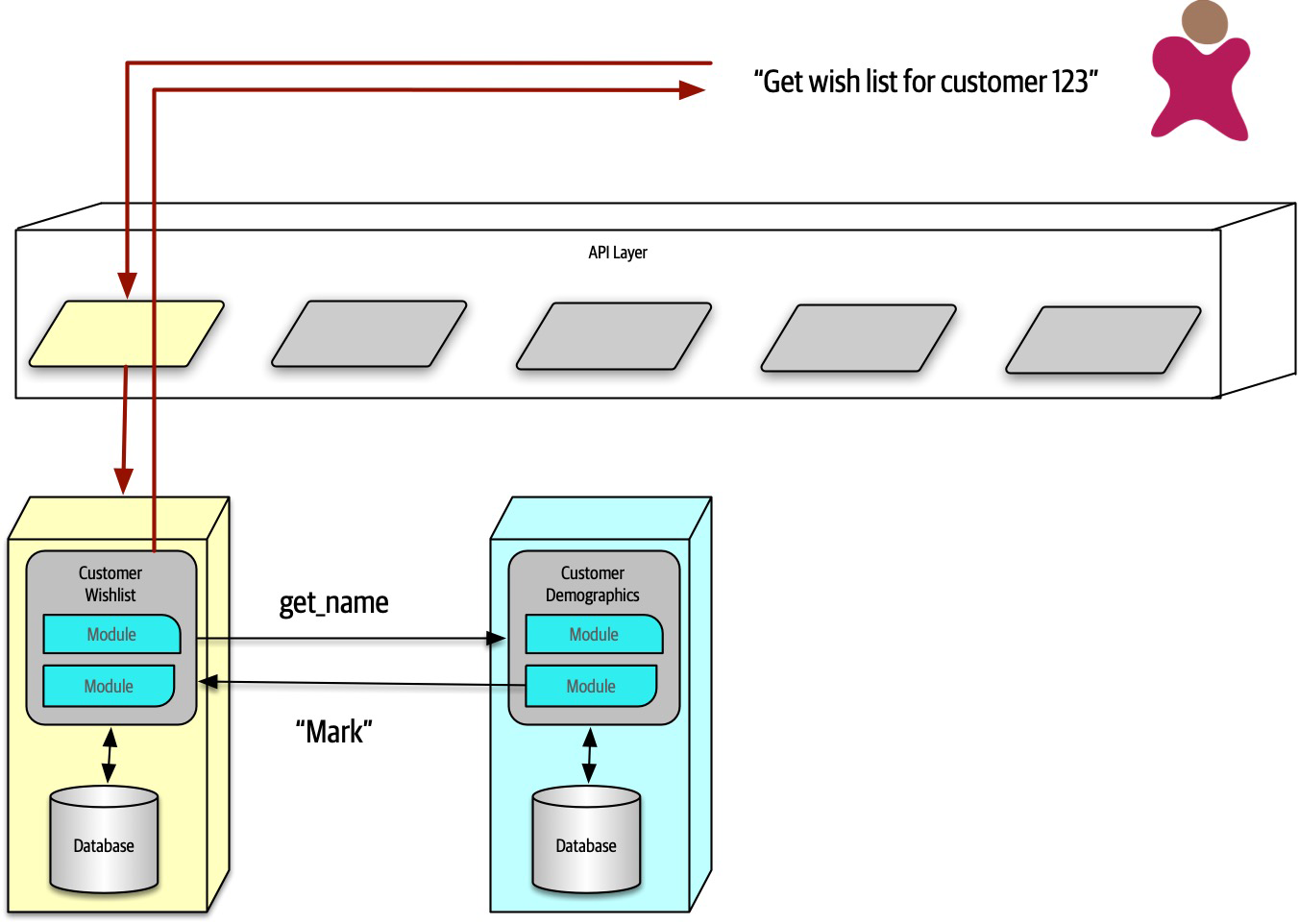

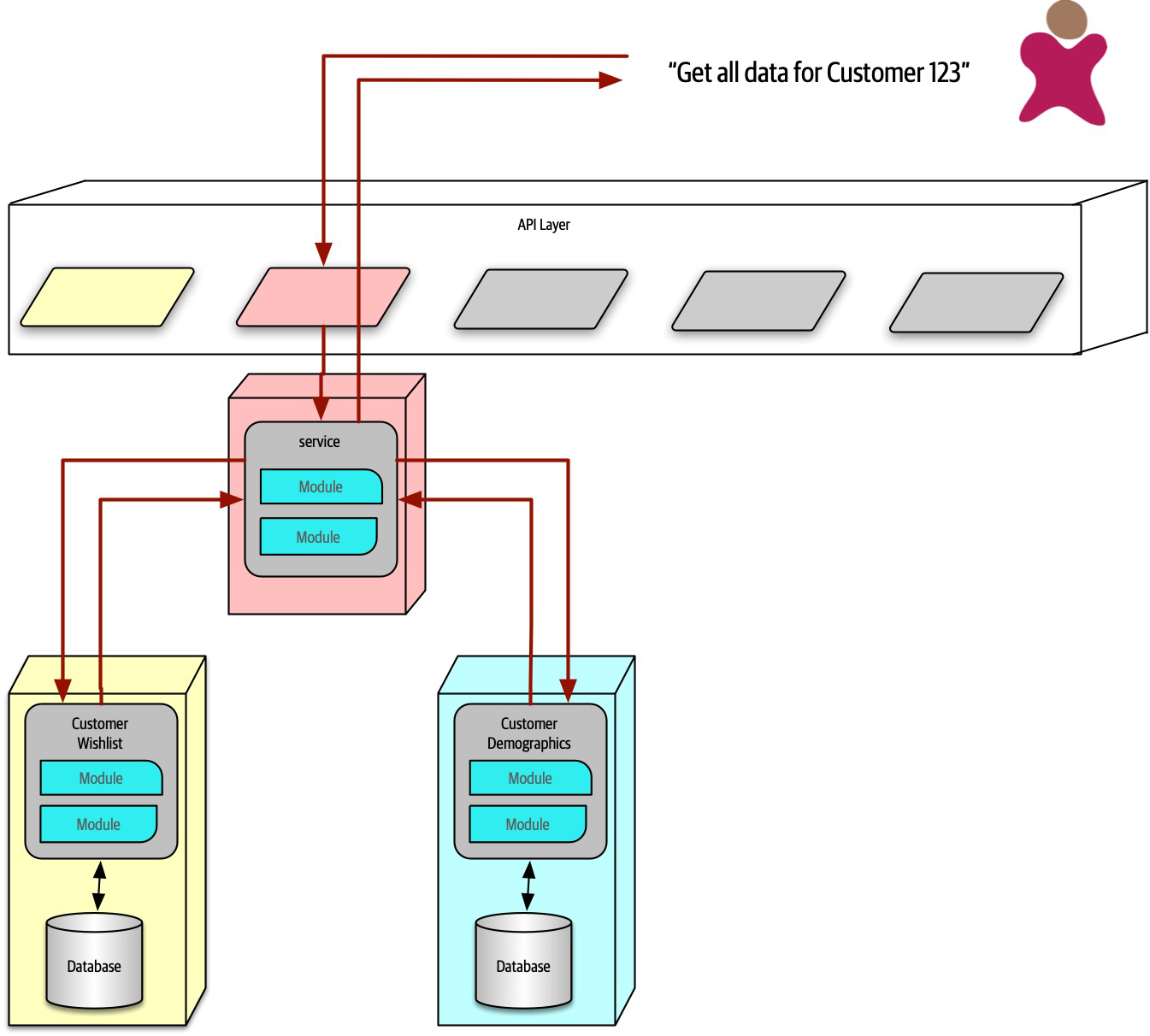

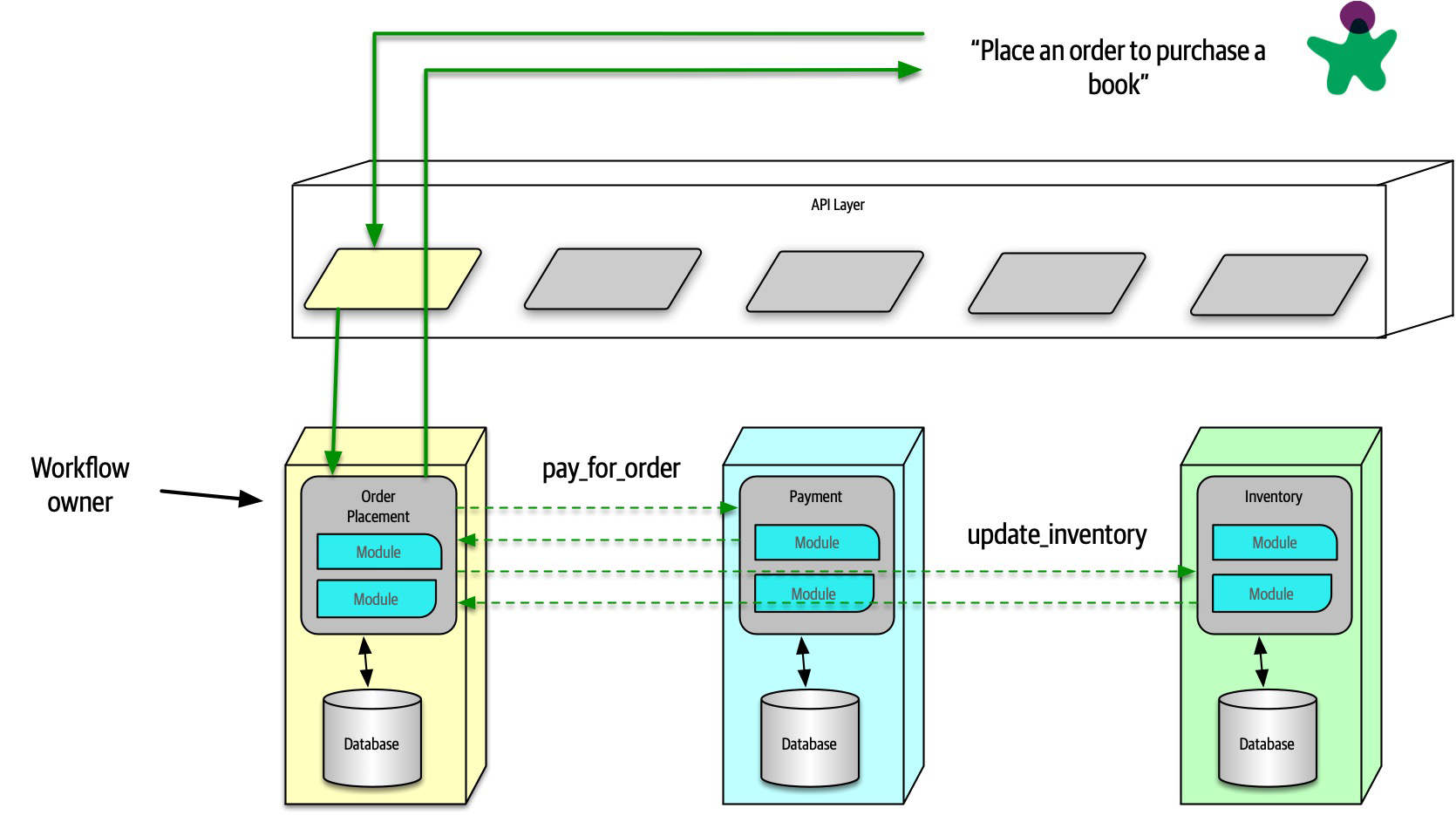

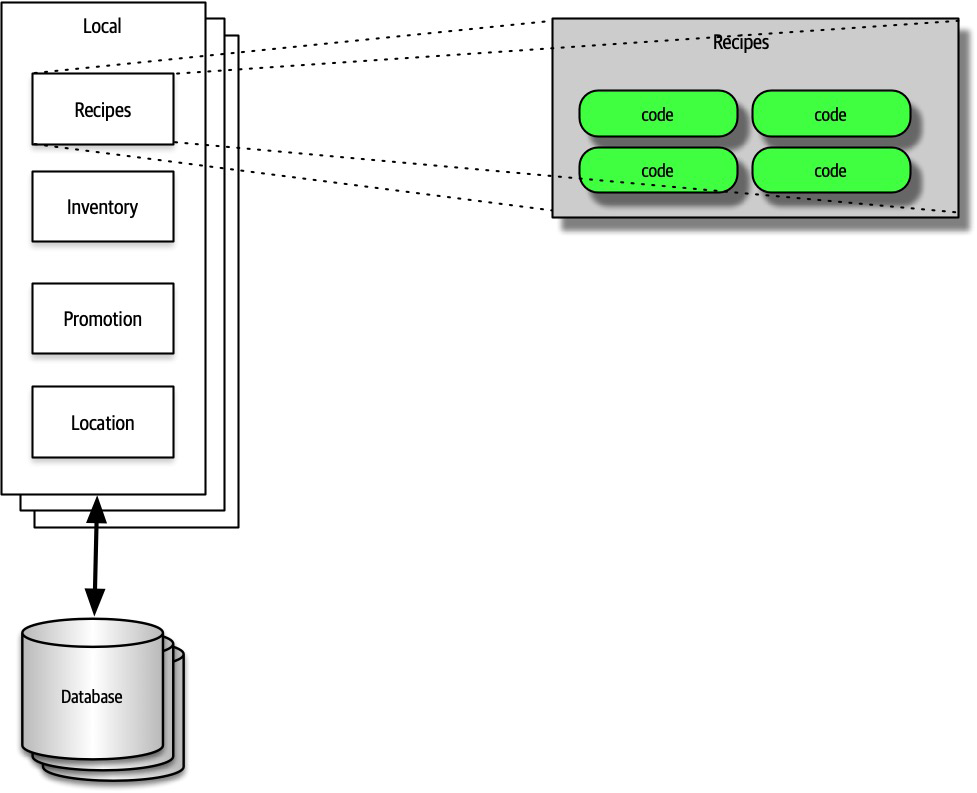

- 17. Microservices Architecture

- 18. Choosing the Appropriate Architecture Style

- III. Techniques and Soft Skills

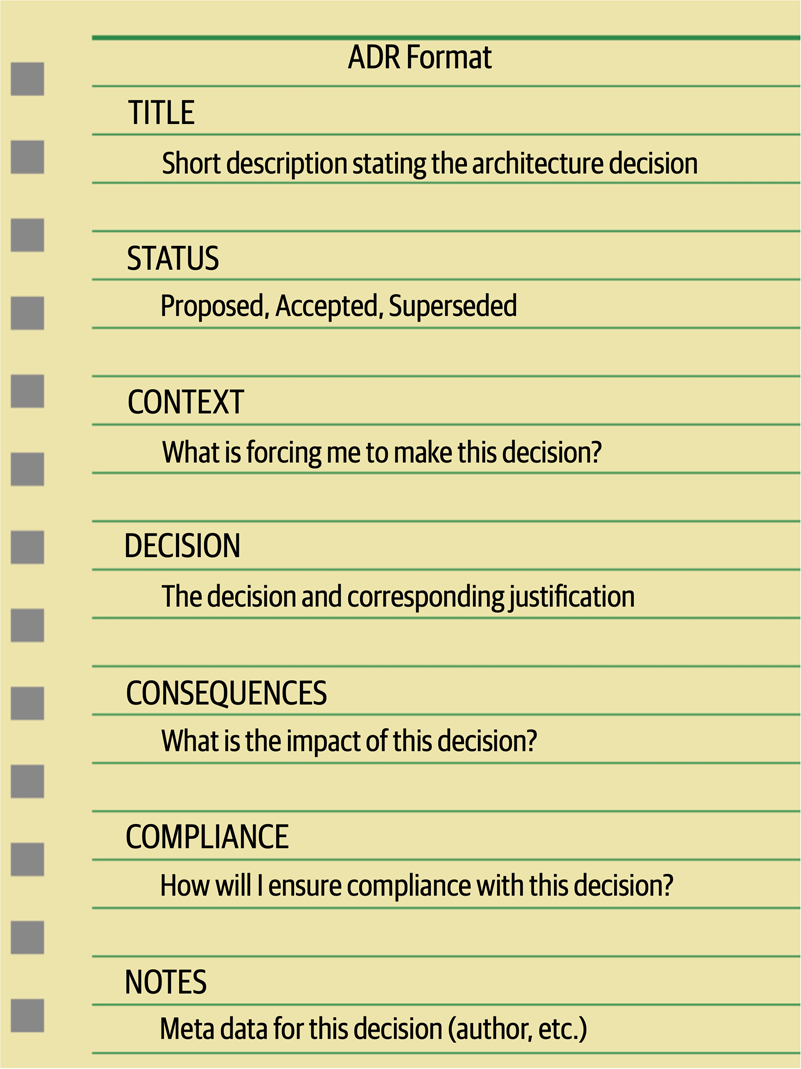

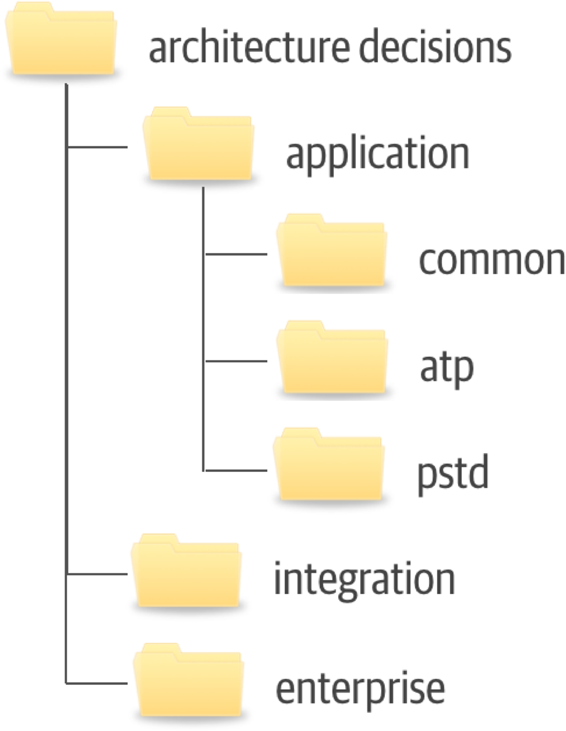

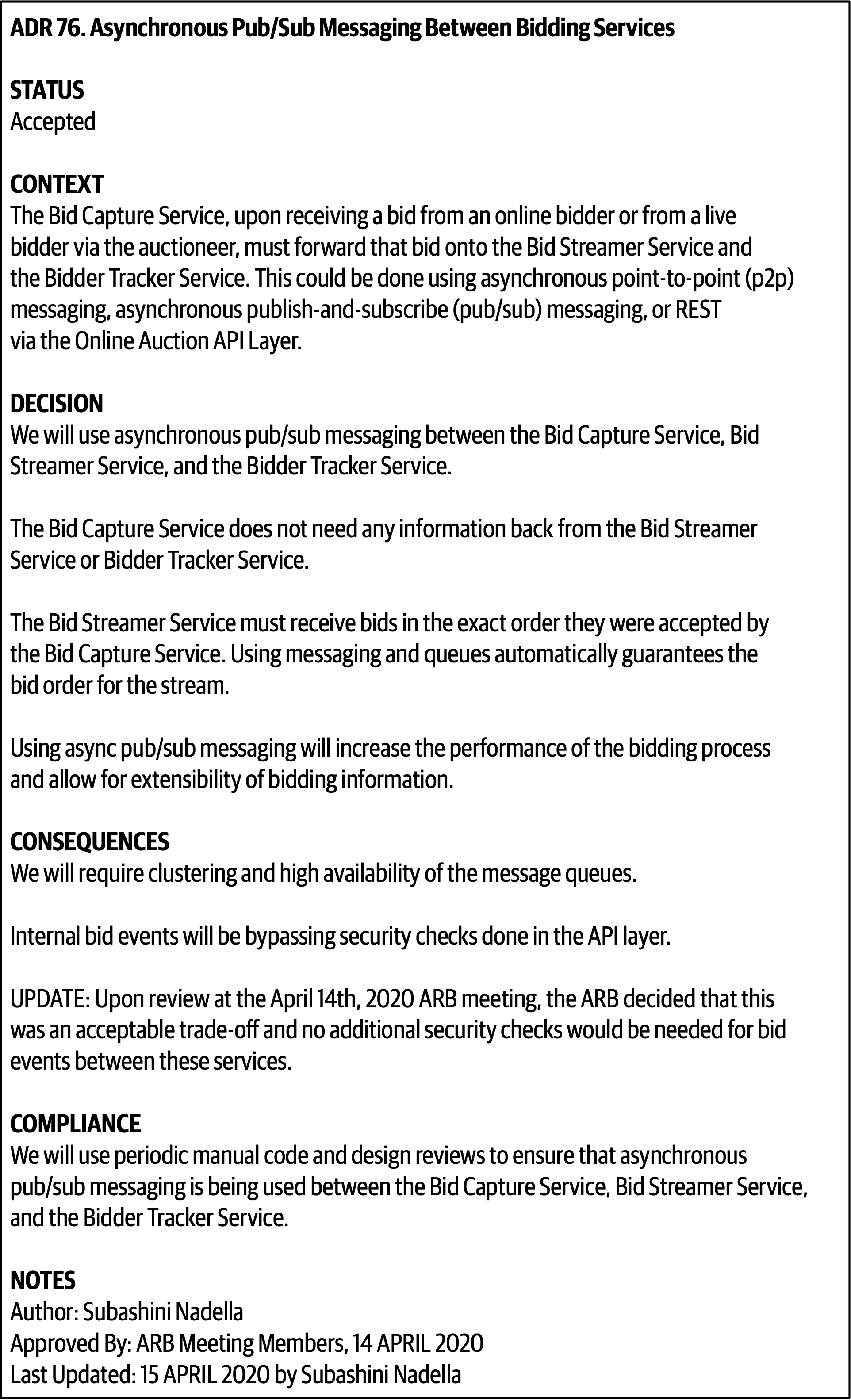

- 19. Architecture Decisions

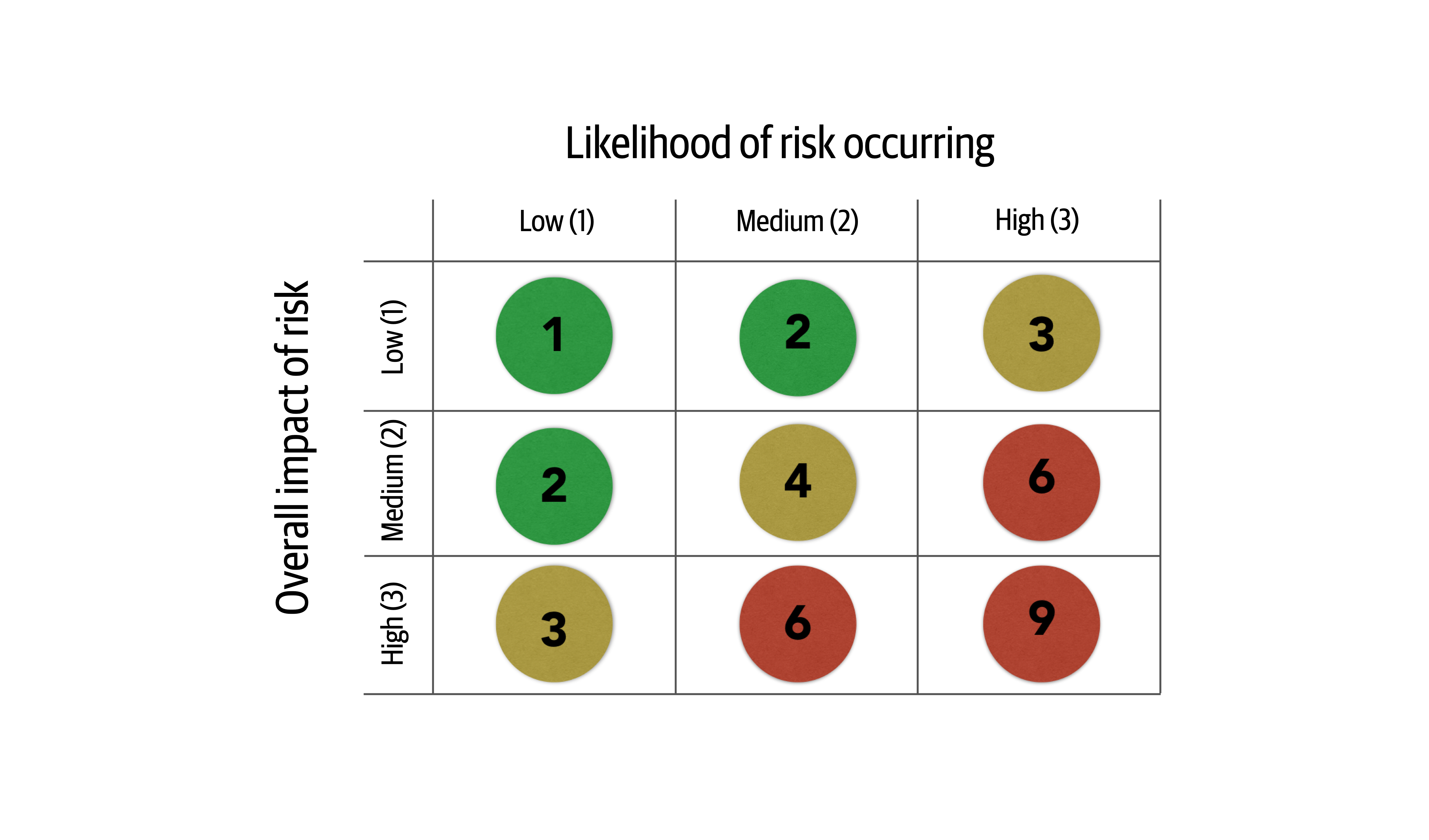

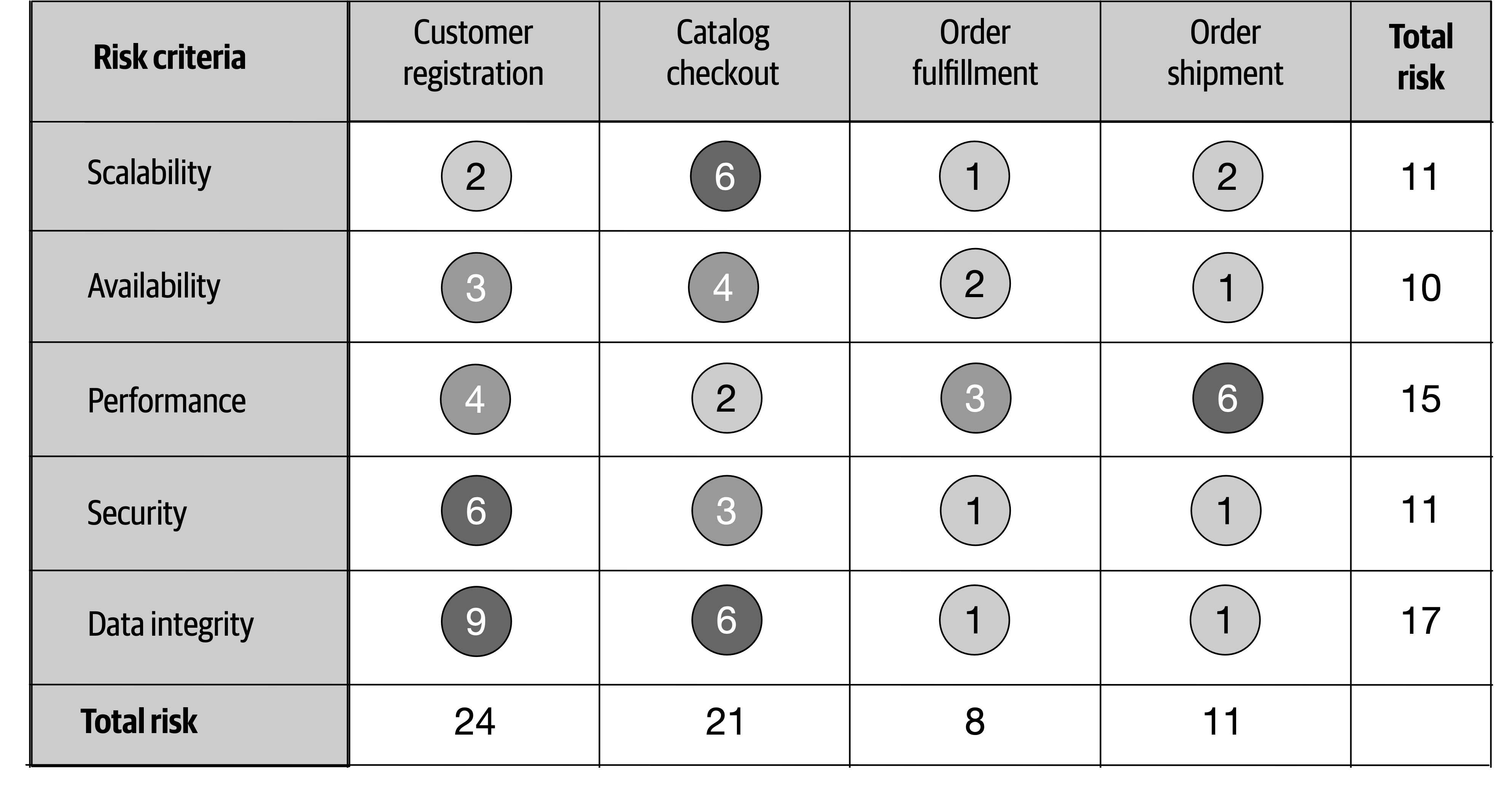

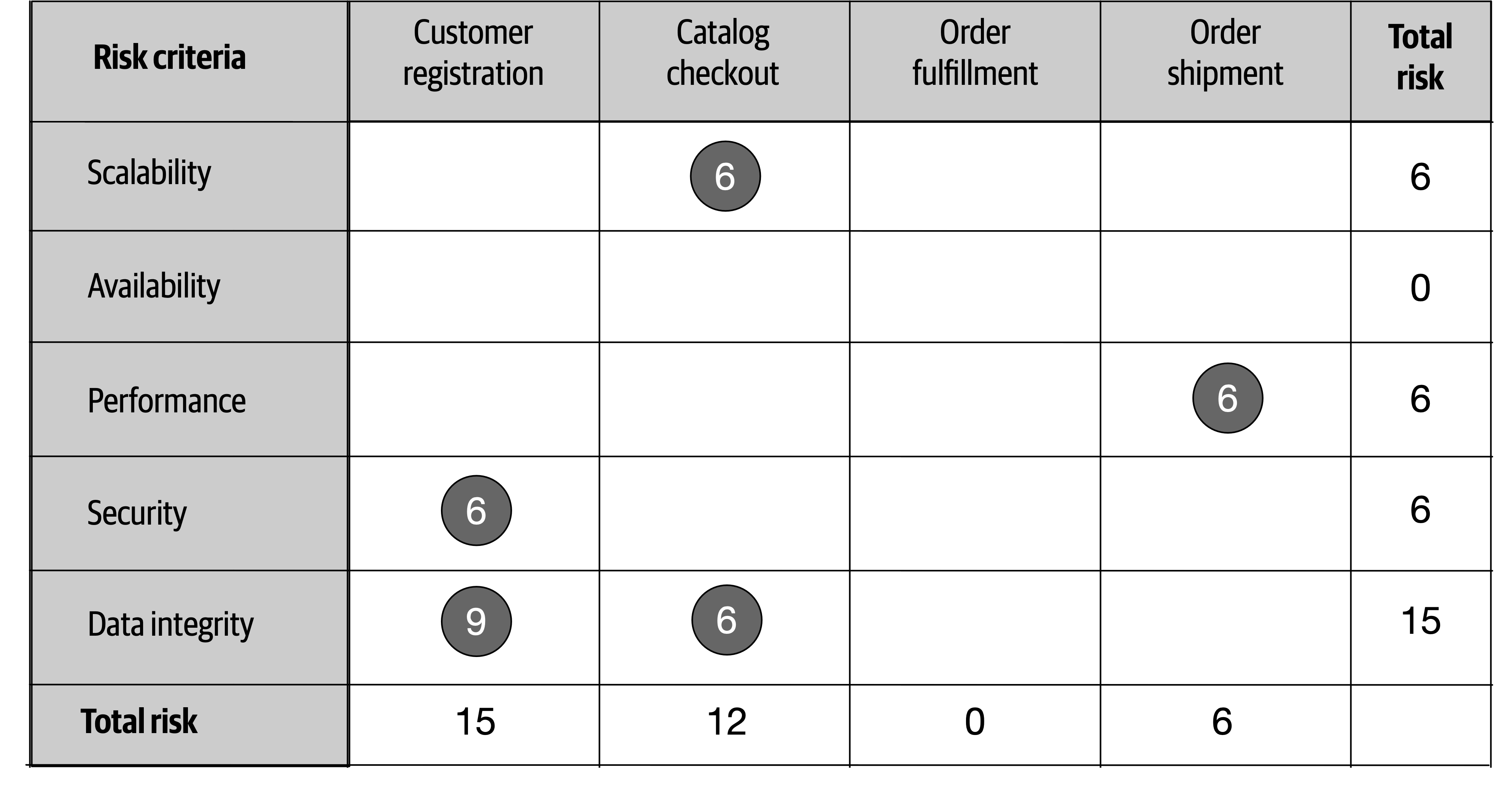

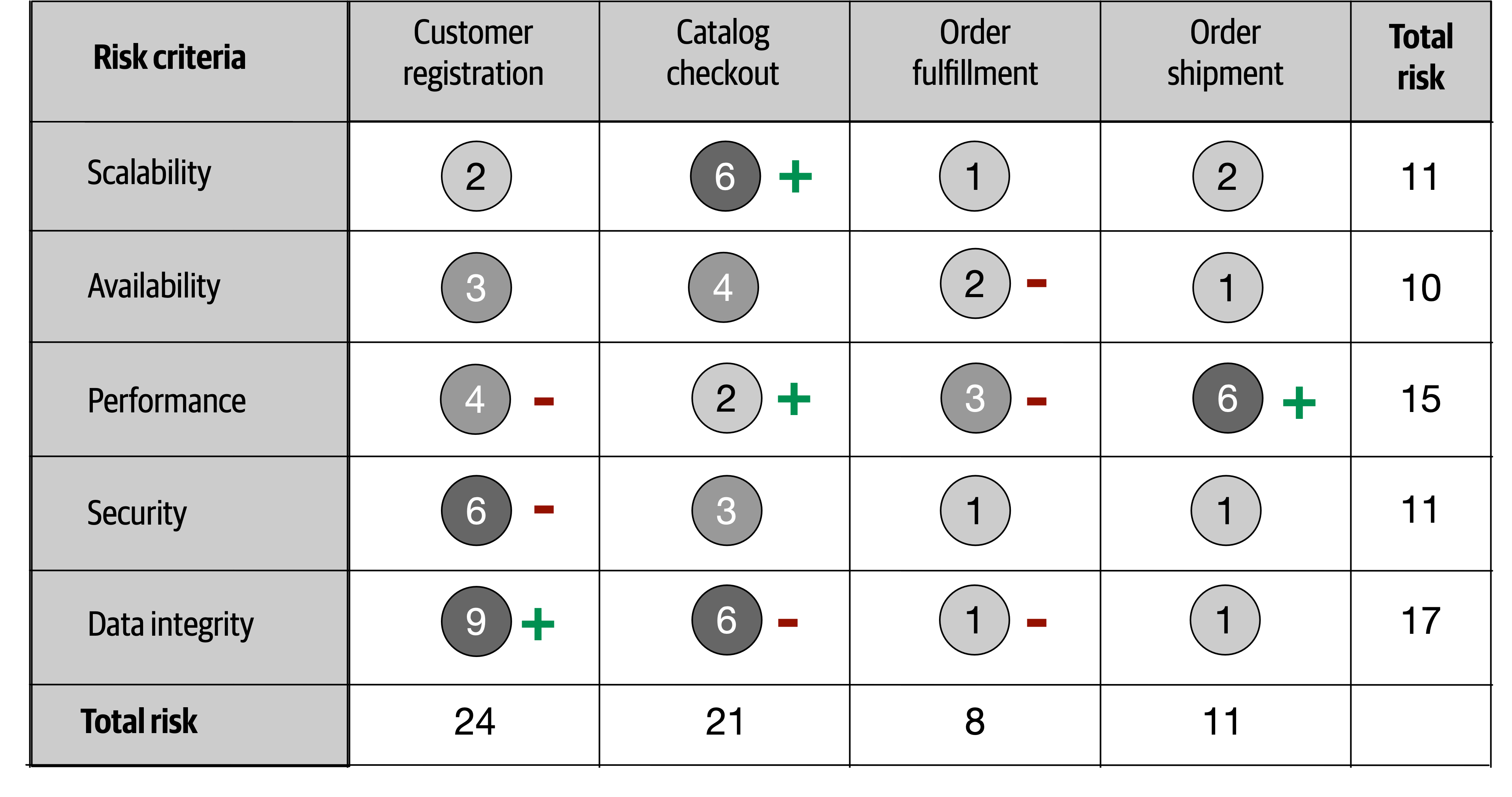

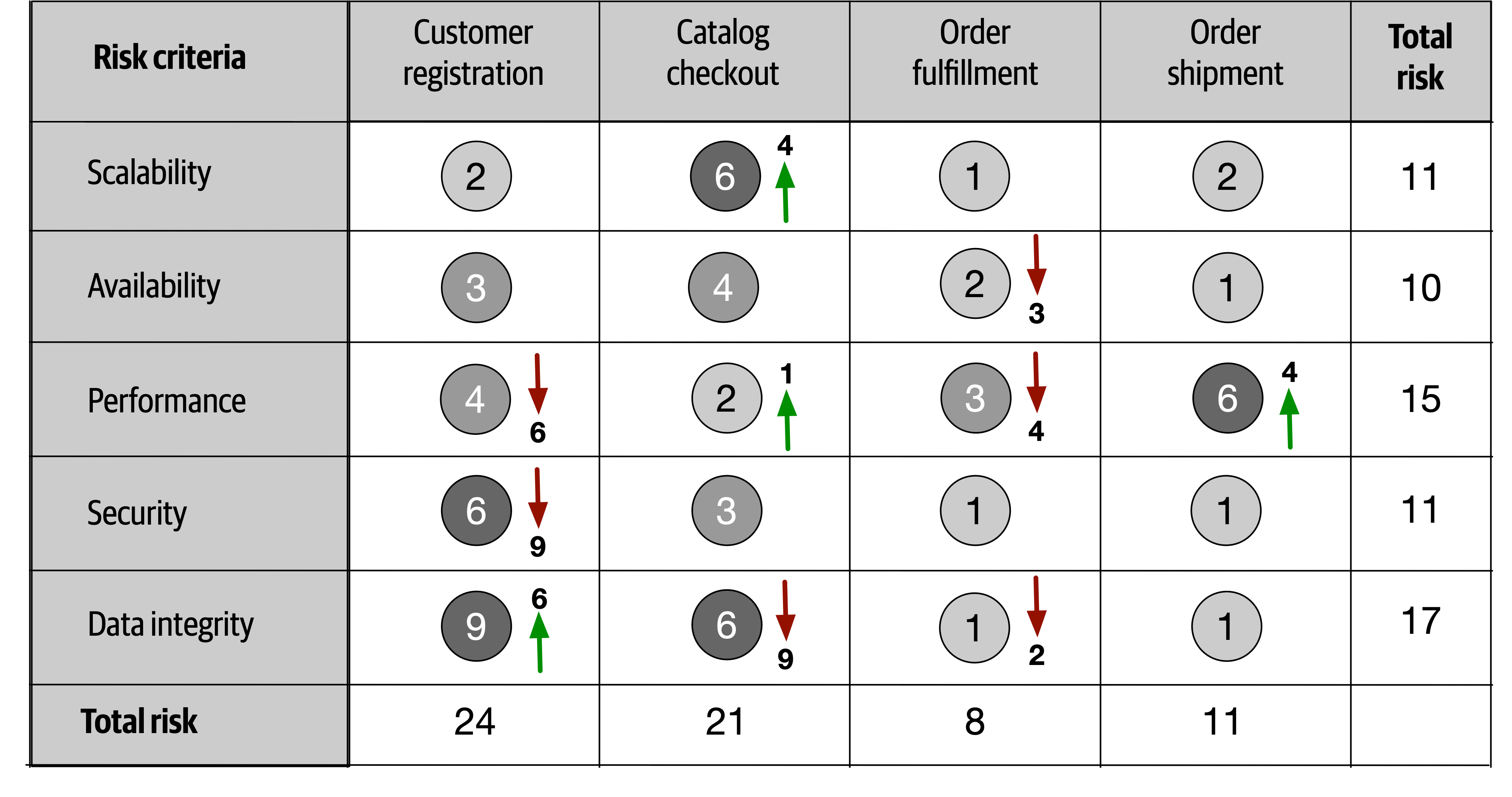

- 20. Analyzing Architecture Risk

- 21. Diagramming and Presenting Architecture

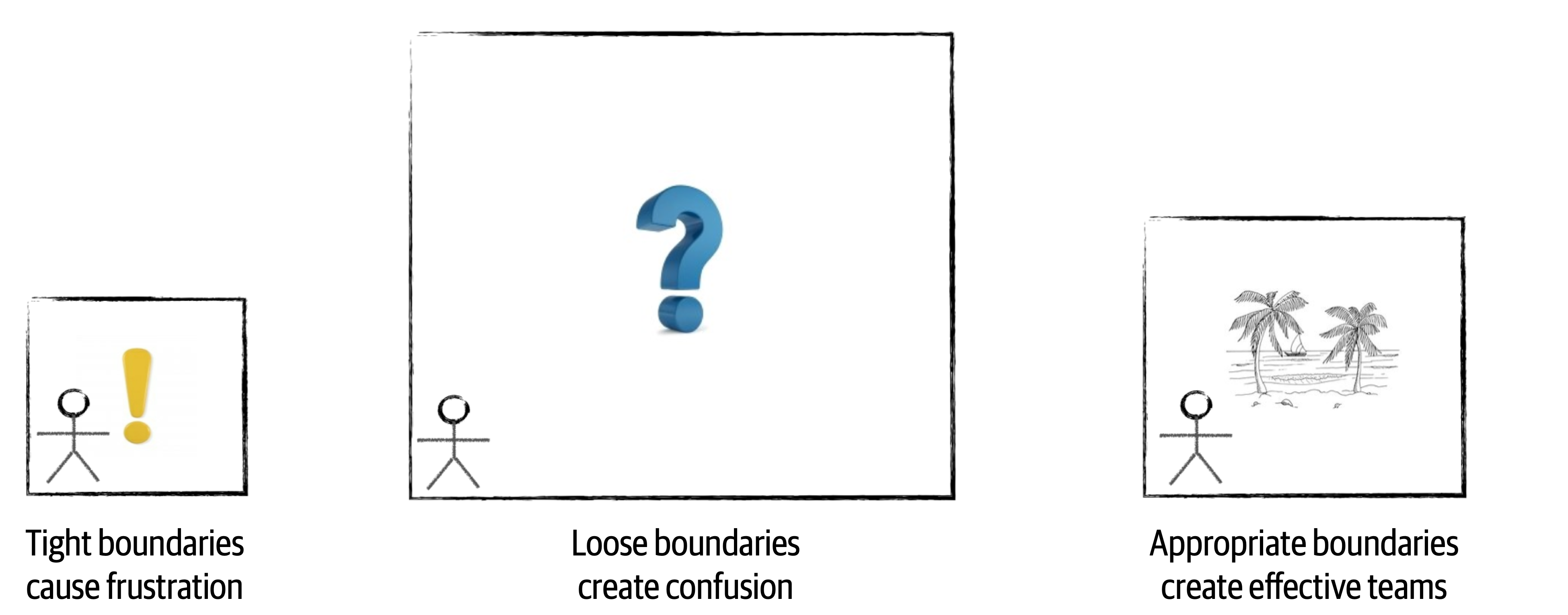

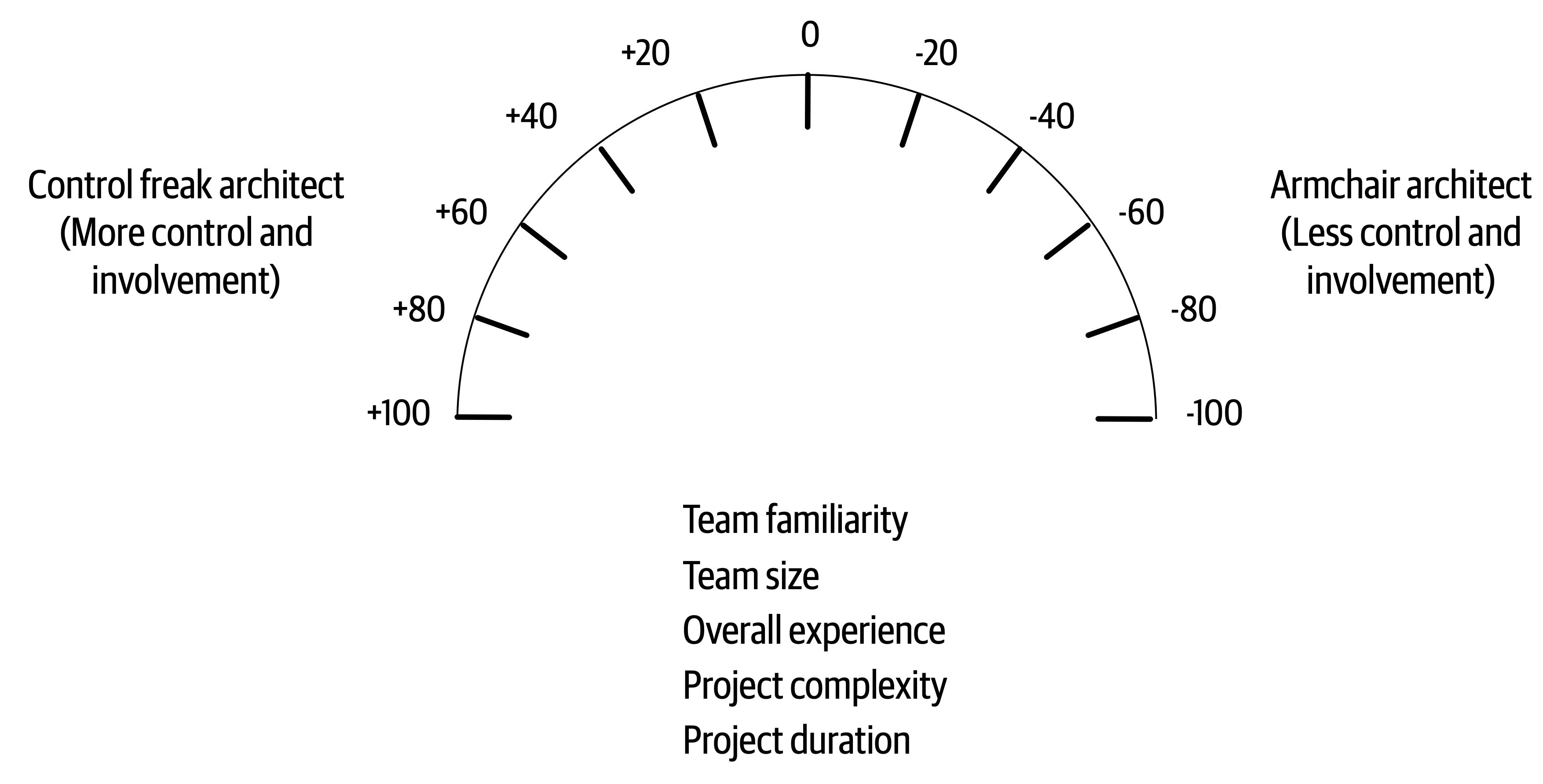

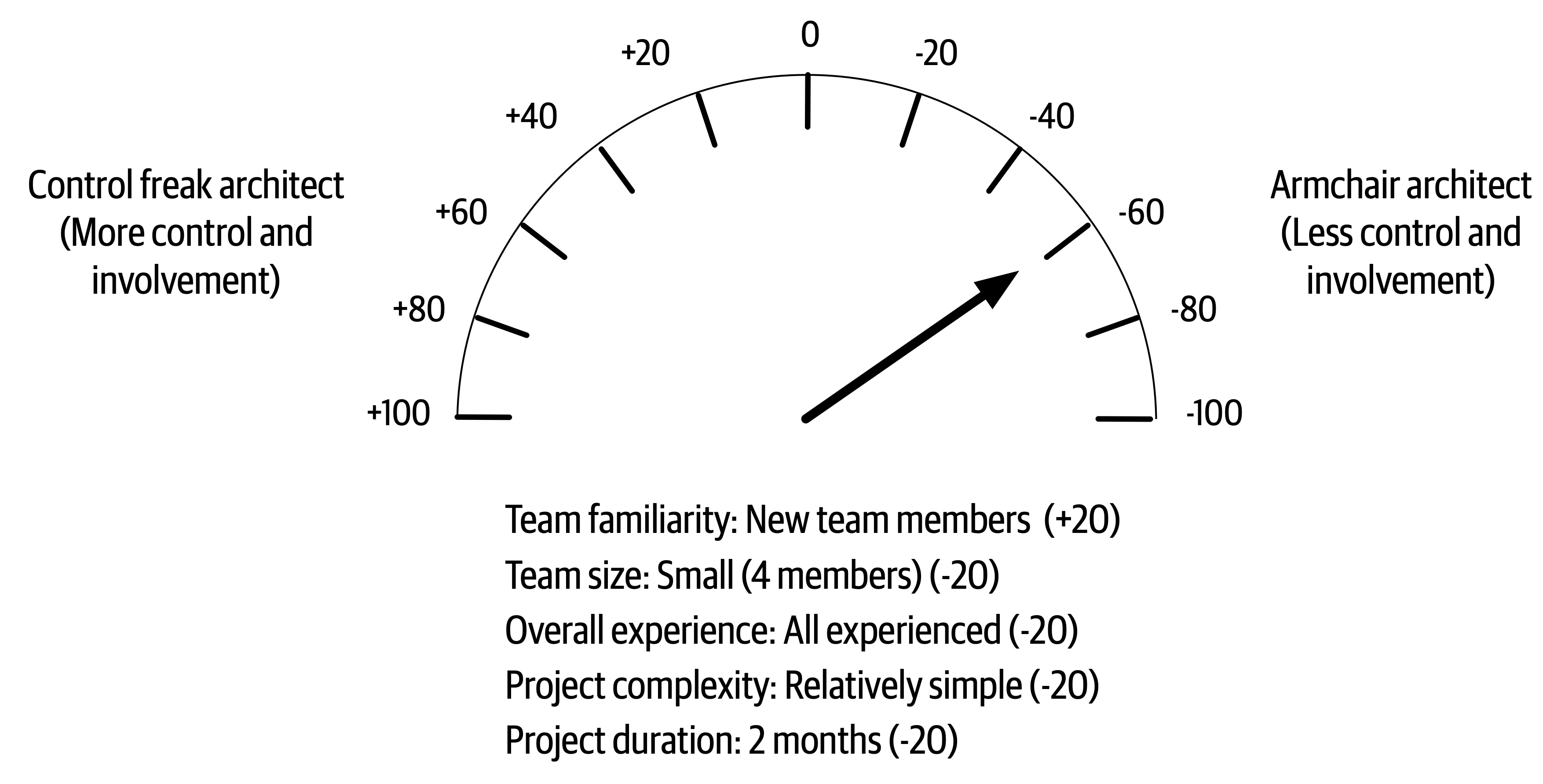

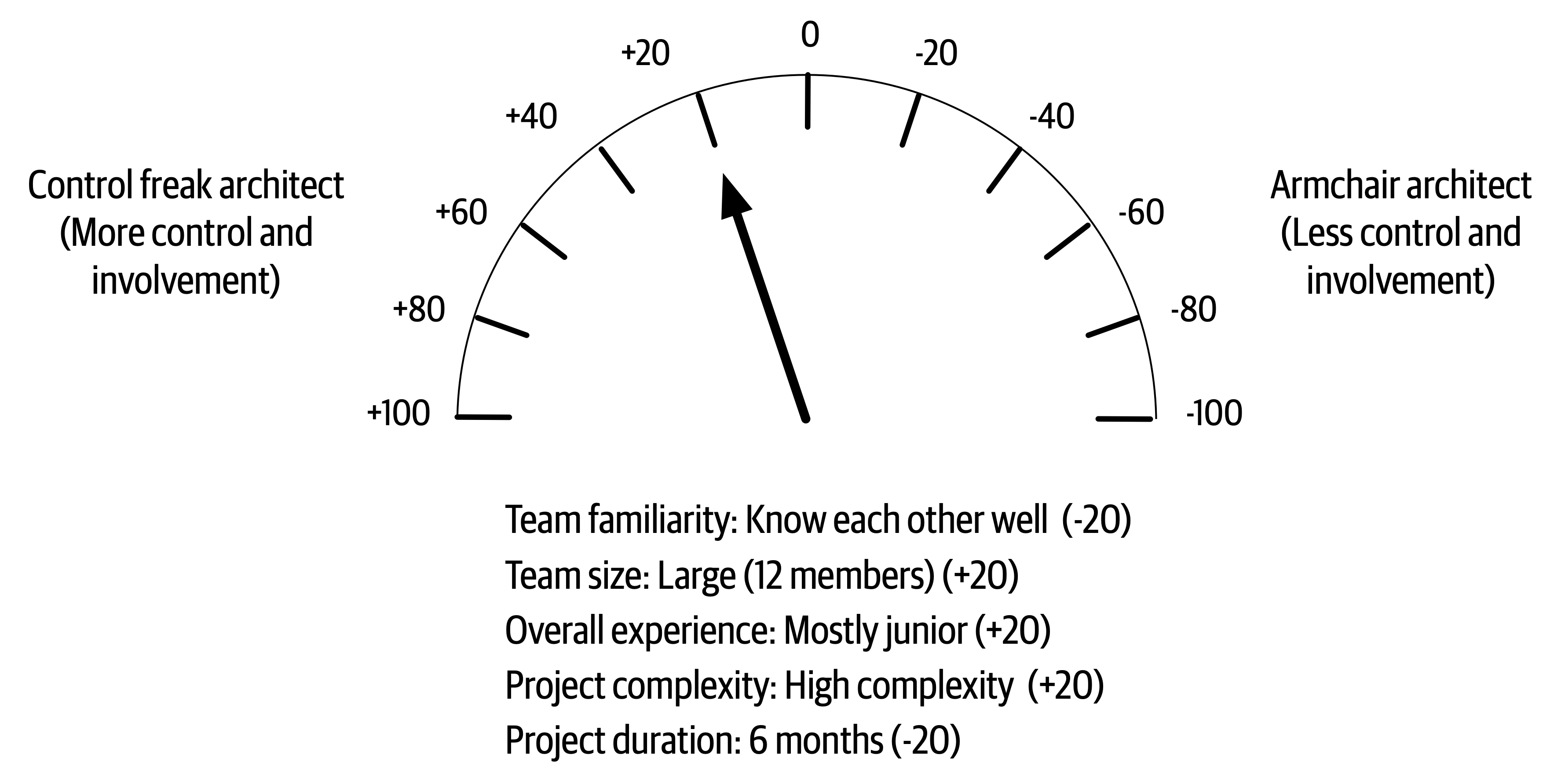

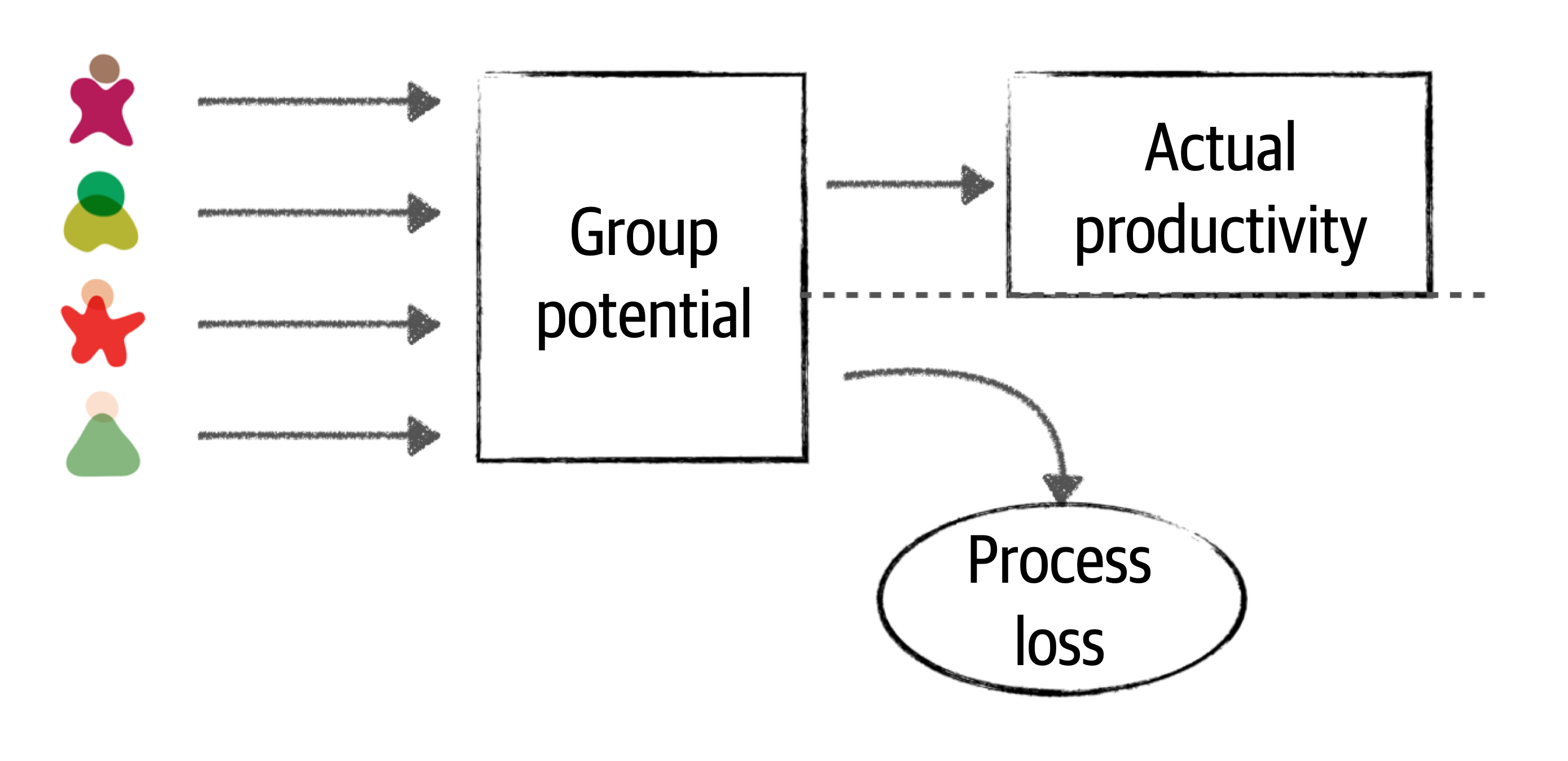

- 22. Making Teams Effective

- 23. Negotiation and Leadership Skills

- 24. Developing a Career Path

- A. Self-Assessment Questions

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Architectural Thinking

- Chapter 3: Modularity

- Chapter 4: Architecture Characteristics Defined

- Chapter 5: Identifying Architecture Characteristics

- Chapter 6: Measuring and Governing Architecture Characteristics

- Chapter 7: Scope of Architecture Characteristics

- Chapter 8: Component-Based Thinking

- Chapter 9: Architecture Styles

- Chapter 10: Layered Architecture Style

- Chapter 11: Pipeline Architecture

- Chapter 12: Microkernel Architecture

- Chapter 13: Service-Based Architecture

- Chapter 14: Event-Driven Architecture Style

- Chapter 15: Space-Based Architecture

- Chapter 16: Orchestration-Driven Service-Oriented Architecture

- Chapter 17: Microservices Architecture

- Chapter 18: Choosing the Appropriate Architecture Style

- Chapter 19: Architecture Decisions

- Chapter 20: Analyzing Architecture Risk

- Chapter 21: Diagramming and Presenting Architecture

- Chapter 22: Making Teams Effective

- Chapter 23: Negotiation and Leadership Skills

- Chapter 24: Developing a Career Path

- Index

Praise for Fundamentals of Software Architecture

Neal and Mark aren’t just outstanding software architects; they are also exceptional teachers. With Fundamentals of Software Architecture, they have managed to condense the sprawling topic of architecture into a concise work that reflects their decades of experience. Whether you’re new to the role or you’ve been a practicing architect for many years, this book will help you be better at your job. I only wish they’d written this earlier in my career.

Nathaniel Schutta, Architect as a Service, ntschutta.io

Mark and Neal set out to achieve a formidable goal—to elucidate the many, layered fundamentals required to excel in software architecture—and they completed their quest. The software architecture field continuously evolves, and the role requires a daunting breadth and depth of knowledge and skills. This book will serve as a guide for many as they navigate their journey to software architecture mastery.

Rebecca J. Parsons, CTO, ThoughtWorks

Mark and Neal truly capture real world advice for technologists to drive architecture excellence. They achieve this by identifying common architecture characteristics and the trade-offs that are necessary to drive success.

Cassie Shum, Technical Director, ThoughtWorks

Fundamentals of Software Architecture

An Engineering Approach

Mark Richards and Neal Ford

Fundamentals of Software Architecture

by Mark Richards and Neal Ford

Copyright © 2020 Mark Richards, Neal Ford. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472.

O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (http://oreilly.com). For more information, contact our corporate/institutional sales department: 800-998-9938 or corporate@oreilly.com.

- Acquisitions Editor: Chris Guzikowski

- Development Editors: Alicia Young and Virginia Wilson

- Production Editor: Christopher Faucher

- Copyeditor: Sonia Saruba

- Proofreader: Amanda Kersey

- Indexer: Ellen Troutman-Zaig

- Interior Designer: David Futato

- Cover Designer: Karen Montgomery

- Illustrator: Rebecca Demarest

- February 2020: First Edition

Revision History for the First Edition

- 2020-01-27: First Release

See http://oreilly.com/catalog/errata.csp?isbn=9781492043454 for release details.

The O’Reilly logo is a registered trademark of O’Reilly Media, Inc. Fundamentals of Software Architecture, the cover image, and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc.

The views expressed in this work are those of the authors, and do not represent the publisher’s views. While the publisher and the authors have used good faith efforts to ensure that the information and instructions contained in this work are accurate, the publisher and the authors disclaim all responsibility for errors or omissions, including without limitation responsibility for damages resulting from the use of or reliance on this work. Use of the information and instructions contained in this work is at your own risk. If any code samples or other technology this work contains or describes is subject to open source licenses or the intellectual property rights of others, it is your responsibility to ensure that your use thereof complies with such licenses and/or rights.

978-1-492-04345-4

[LSI]

Preface: Invalidating Axioms

- Axiom

A statement or proposition which is regarded as being established, accepted, or self-evidently true.

Mathematicians create theories based on axioms, assumptions for things indisputably true. Software architects also build theories atop axioms, but the software world is, well, softer than mathematics: fundamental things continue to change at a rapid pace, including the axioms we base our theories upon.

The software development ecosystem exists in a constant state of dynamic equilibrium: while it exists in a balanced state at any given point in time, it exhibits dynamic behavior over the long term. A great modern example of the nature of this ecosystem follows the ascension of containerization and the attendant changes: tools like Kubernetes didn’t exist a decade ago, yet now entire software conferences exist to service its users. The software ecosystem changes chaotically: one small change causes another small change; when repeated hundreds of times, it generates a new ecosystem.

Architects have an important responsibility to question assumptions and axioms left over from previous eras. Many of the books about software architecture were written in an era that only barely resembles the current world. In fact, the authors believe that we must question fundamental axioms on a regular basis, in light of improved engineering practices, operational ecosystems, software development processes—everything that makes up the messy, dynamic equilibrium where architects and developers work each day.

Careful observers of software architecture over time witnessed an evolution of capabilities. Starting with the engineering practices of Extreme Programming, continuing with Continuous Delivery, the DevOps revolution, microservices, containerization, and now cloud-based resources, all of these innovations led to new capabilities and trade-offs. As capabilities changed, so did architects’ perspectives on the industry. For many years, the tongue-in-cheek definition of software architecture was “the stuff that’s hard to change later.” Later, the microservices architecture style appeared, where change is a first-class design consideration.

Each new era requires new practices, tools, measurements, patterns, and a host of other changes. This book looks at software architecture in modern light, taking into account all the innovations from the last decade, along with some new metrics and measures suited to today’s new structures and perspectives.

The subtitle of our book is “An Engineering Approach.” Developers have long wished to change software development from a craft, where skilled artisans can create one-off works, to an engineering discipline, which implies repeatability, rigor, and effective analysis. While software engineering still lags behind other types of engineering disciplines by many orders of magnitude (to be fair, software is a very young discipline compared to most other types of engineering), architects have made huge improvements, which we’ll discuss. In particular, modern Agile engineering practices have allowed great strides in the types of systems that architects design.

We also address the critically important issue of trade-off analysis. As a software developer, it’s easy to become enamored with a particular technology or approach. But architects must always soberly assess the good, bad, and ugly of every choice, and virtually nothing in the real world offers convenient binary choices—everything is a trade-off. Given this pragmatic perspective, we strive to eliminate value judgments about technology and instead focus on analyzing trade-offs to equip our readers with an analytic eye toward technology choices.

This book won’t make someone a software architecture overnight—it’s a nuanced field with many facets. We want to provide existing and burgeoning architects a good modern overview of software architecture and its many aspects, from structure to soft skills. While this book covers well-known patterns, we take a new approach, leaning on lessons learned, tools, engineering practices, and other input. We take many existing axioms in software architecture and rethink them in light of the current ecosystem, and design architectures, taking the modern landscape into account.

Conventions Used in This Book

The following typographical conventions are used in this book:

- Italic

-

Indicates new terms, URLs, email addresses, filenames, and file extensions.

Constant width-

Used for program listings, as well as within paragraphs to refer to program elements such as variable or function names, databases, data types, environment variables, statements, and keywords.

Constant width bold-

Shows commands or other text that should be typed literally by the user.

Constant width italic-

Shows text that should be replaced with user-supplied values or by values determined by context.

Tip

This element signifies a tip or suggestion.

Using Code Examples

Supplemental material (code examples, exercises, etc.) is available for download at http://fundamentalsofsoftwarearchitecture.com.

If you have a technical question or a problem using the code examples, please send email to bookquestions@oreilly.com.

This book is here to help you get your job done. In general, if example code is offered with this book, you may use it in your programs and documentation. You do not need to contact us for permission unless you’re reproducing a significant portion of the code. For example, writing a program that uses several chunks of code from this book does not require permission. Selling or distributing examples from O’Reilly books does require permission. Answering a question by citing this book and quoting example code does not require permission. Incorporating a significant amount of example code from this book into your product’s documentation does require permission.

We appreciate, but generally do not require, attribution. An attribution usually includes the title, author, publisher, and ISBN. For example: “Fundamentals of Software Architecture by Mark Richards and Neal Ford (O’Reilly). Copyright 2020 Mark Richards, Neal Ford, 978-1-492-04345-4.”

If you feel your use of code examples falls outside fair use or the permission given above, feel free to contact us at permissions@oreilly.com.

O’Reilly Online Learning

Note

For more than 40 years, O’Reilly Media has provided technology and business training, knowledge, and insight to help companies succeed.

Our unique network of experts and innovators share their knowledge and expertise through books, articles, conferences, and our online learning platform. O’Reilly’s online learning platform gives you on-demand access to live training courses, in-depth learning paths, interactive coding environments, and a vast collection of text and video from O’Reilly and 200+ other publishers. For more information, please visit http://oreilly.com.

How to Contact Us

Please address comments and questions concerning this book to the publisher:

- O’Reilly Media, Inc.

- 1005 Gravenstein Highway North

- Sebastopol, CA 95472

- 800-998-9938 (in the United States or Canada)

- 707-829-0515 (international or local)

- 707-829-0104 (fax)

We have a web page for this book, where we list errata, examples, and any additional information. You can access this page at https://oreil.ly/fundamentals-of-software-architecture.

Email bookquestions@oreilly.com to comment or ask technical questions about this book.

For more information about our books, courses, conferences, and news, see our website at http://www.oreilly.com.

Find us on Facebook: http://facebook.com/oreilly

Follow us on Twitter: http://twitter.com/oreillymedia

Watch us on YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/oreillymedia

Acknowledgments

Mark and Neal would like to thank all the people who attended our classes, workshops, conference sessions, user group meetings, as well as all the other people who listened to versions of this material and provided invaluable feedback. We would also like to thank the publishing team at O’Reilly, who made this as painless an experience as writing a book can be. We would also like to thank No Stuff Just Fluff director Jay Zimmerman for creating a conference series that allows good technical content to grow and spread, and all the other speakers whose feedback and tear-soaked shoulders we appreciate. We would also like to thank a few random oases of sanity-preserving and idea-sparking groups that have names like Pasty Geeks and the Hacker B&B.

Acknowledgments from Mark Richards

In addition to the preceding acknowledgments, I would like to thank my lovely wife, Rebecca. Taking everything else on at home and sacrificing the opportunity to work on your own book allowed me to do additional consulting gigs and speak at more conferences and training classes, giving me the opportunity to practice and hone the material for this book. You are the best.

Acknowledgments from Neal Ford

Neal would like to thank his extended family, ThoughtWorks as a collective, and Rebecca Parsons and Martin Fowler as individual parts of it. ThoughtWorks is an extraordinary group who manage to produce value for customers while keeping a keen eye toward why things work so that that we can improve them. ThoughtWorks supported this book in many myriad ways and continues to grow ThoughtWorkers who challenge and inspire every day. Neal would also like to thank our neighborhood cocktail club for a regular escape from routine. Lastly, Neal would like to thank his wife, Candy, whose tolerance for things like book writing and conference speaking apparently knows no bounds. For decades she’s kept me grounded and sane enough to function, and I hope she will for decades more as the love of my life.

Chapter 1. Introduction

The job “software architect” appears near the top of numerous lists of best jobs across the world.

Architecture is about the important stuff…whatever that is.

Ralph Johnson

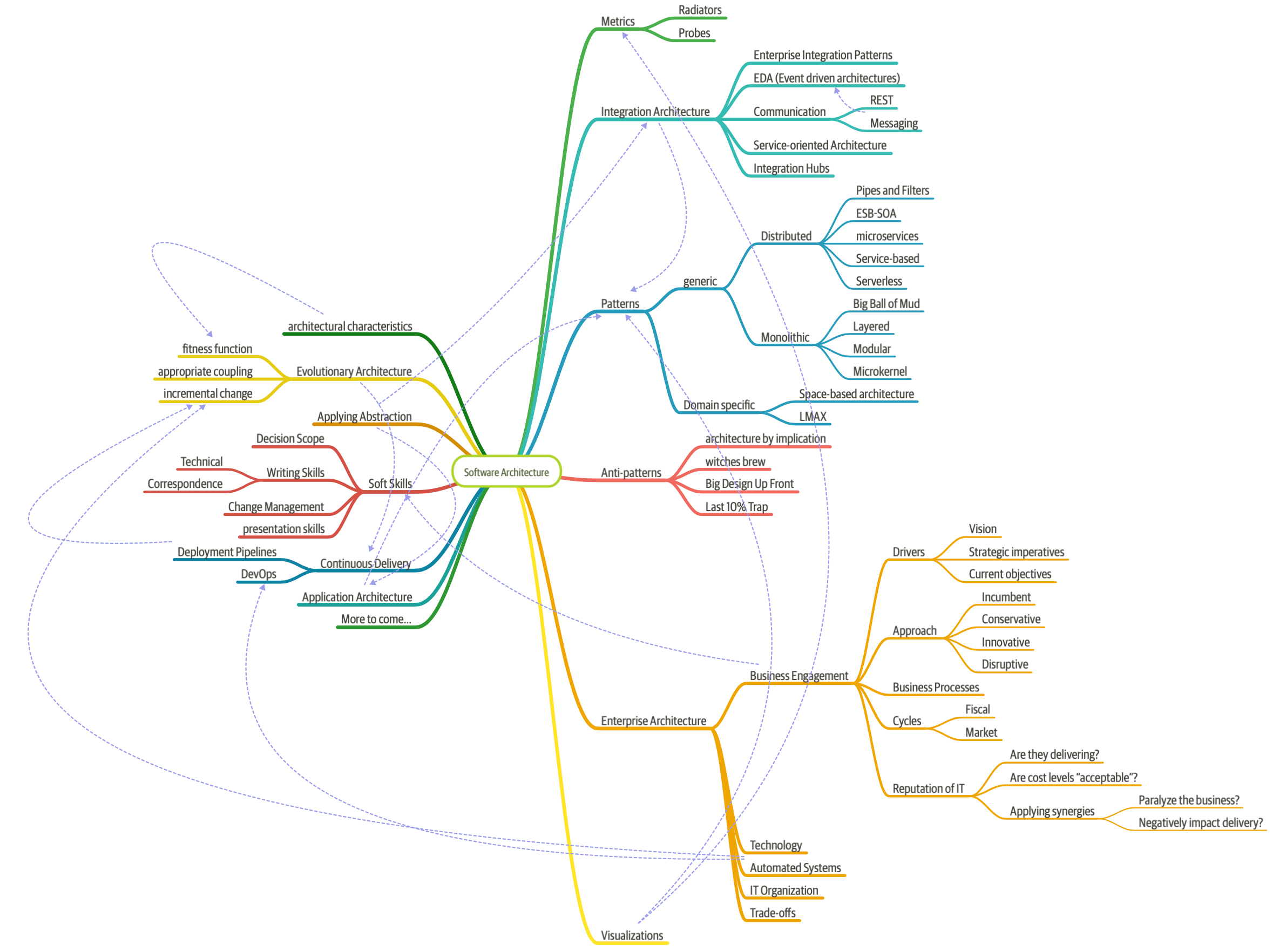

When pressed, we created the mindmap shown in Figure 1-1, which is woefully incomplete but indicative of the scope of software architecture. We will, in fact, offer our definition of software architecture shortly.

Second, as illustrated in the mindmap, the role of software architect embodies a massive amount and scope of responsibility that continues to expand. A decade ago, software architects dealt only with the purely technical aspects of architecture, like modularity, components, and patterns. Since then, because of new architectural styles that leverage a wider swath of capabilities (like microservices), the role of software architect has expanded. We cover the many intersections of architecture and the remainder of the organization in “Intersection of Architecture and…”.

Figure 1-1. The responsibilities of a software architect encompass technical abilities, soft skills, operational awareness, and a host of others

Third, software architecture is a constantly moving target because of the rapidly evolving software development ecosystem. Any definition cast today will be hopelessly outdated in a few years. The Wikipedia definition of software architecture provides a reasonable overview, but many statements are outdated, such as “Software architecture is about making fundamental structural choices which are costly to change once implemented.” Yet architects designed modern architectural styles like microservices with the idea of incremental built in—it is no longer expensive to make structural changes in microservices. Of course, that capability means trade-offs with other concerns, such as coupling. Many books on software architecture treat it as a static problem; once solved, we can safely ignore it. However, we recognize the inherent dynamic nature of software architecture, including the definition itself, throughout the book.

Fourth, much of the material about software architecture has only historical relevance. Readers of the Wikipedia page won’t fail to notice the bewildering array of acronyms and cross-references to an entire universe of knowledge. Yet, many of these acronyms represent outdated or failed attempts. Even solutions that were perfectly valid a few years ago cannot work now because the context has changed. The history of software architecture is littered with things architects have tried, only to realize the damaging side effects. We cover many of those lessons in this book.

Why a book on software architecture fundamentals now? The scope of software architecture isn’t the only part of the development world that constantly changes. New technologies, techniques, capabilities…in fact, it’s easier to find things that haven’t changed over the last decade than to list all the changes. Software architects must make decisions within this constantly changing ecosystem. Because everything changes, including foundations upon which we make decisions, architects should reexamine some core axioms that informed earlier writing about software architecture. For example, earlier books about software architecture don’t consider the impact of DevOps because it didn’t exist when these books were written.

Defining Software Architecture

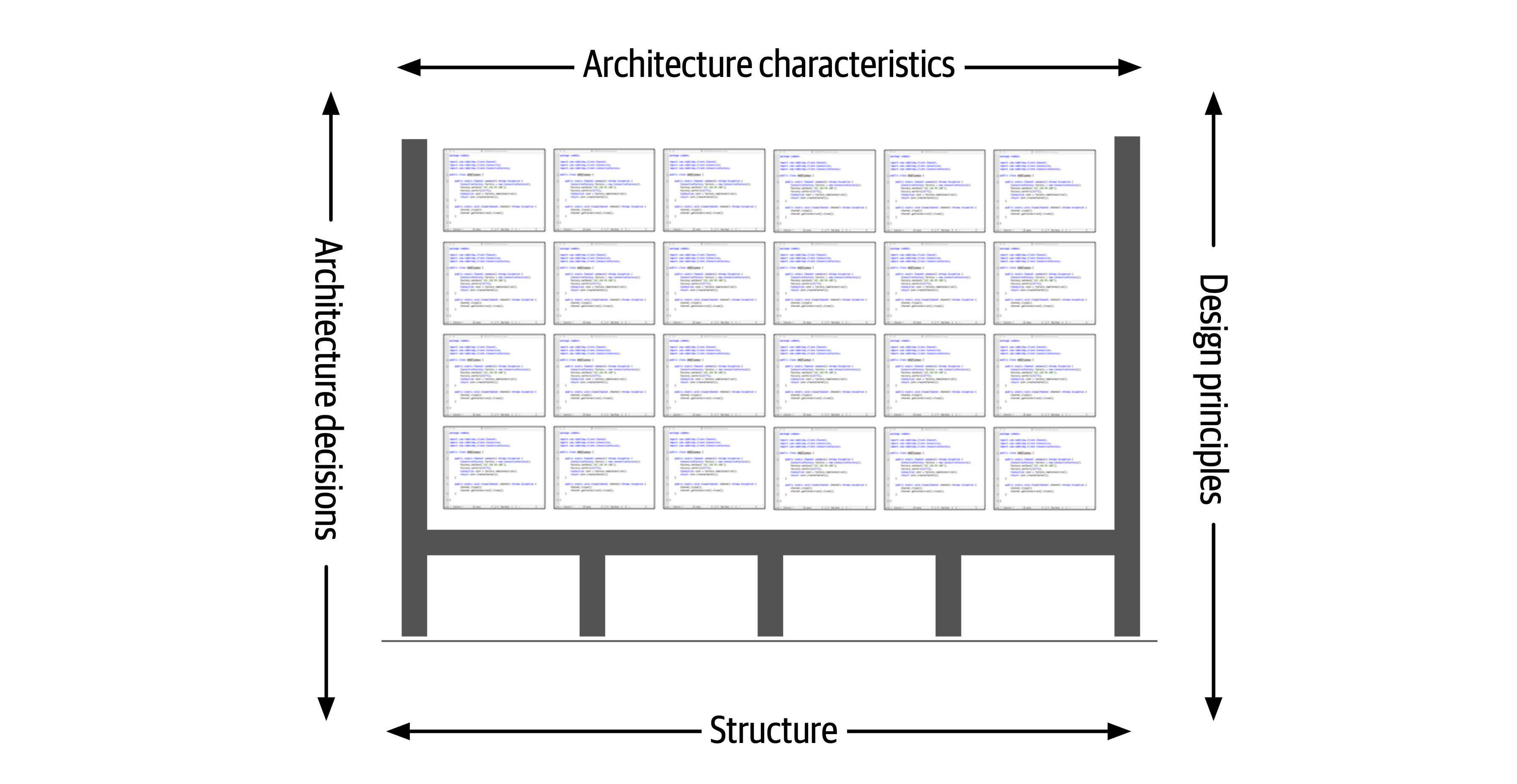

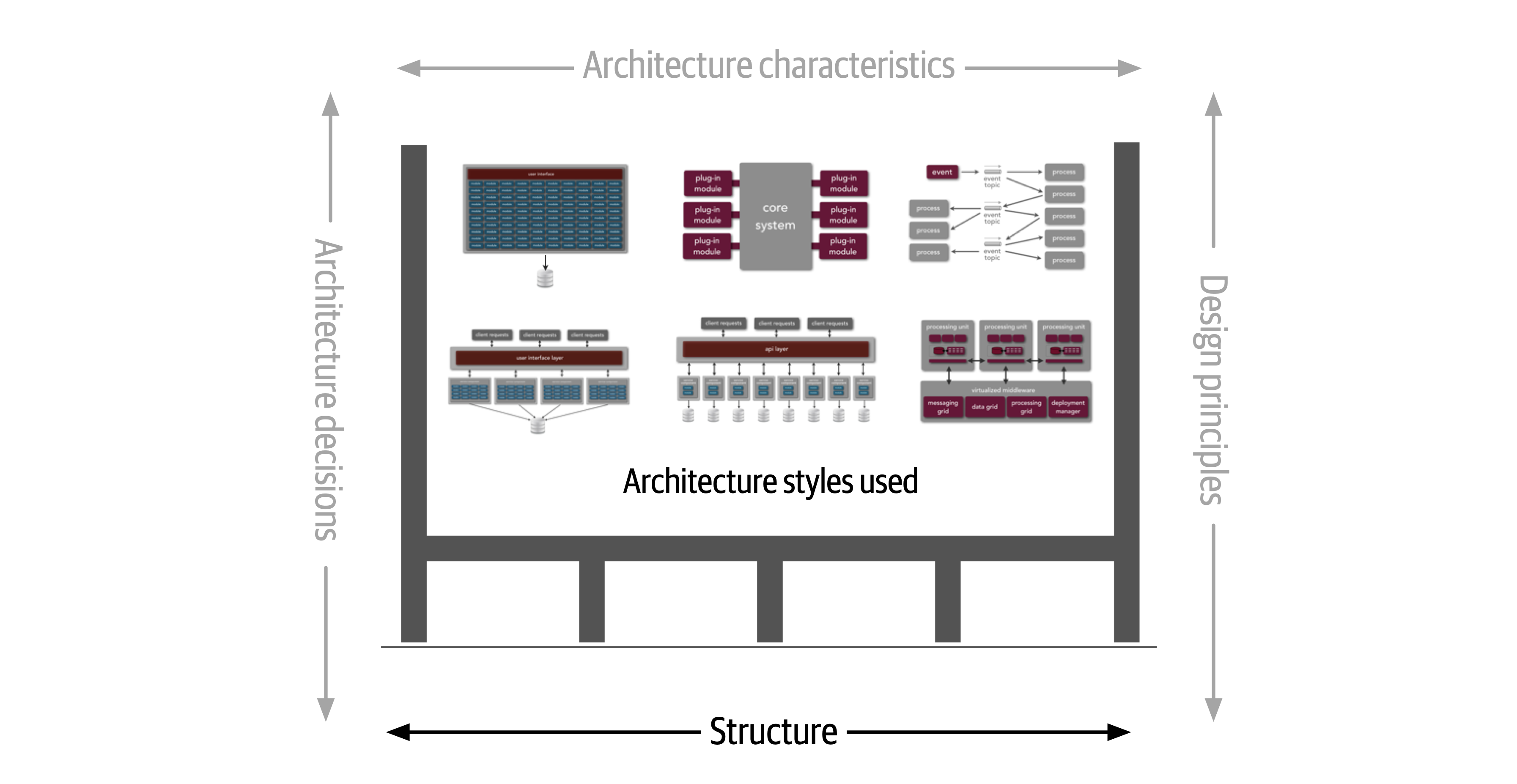

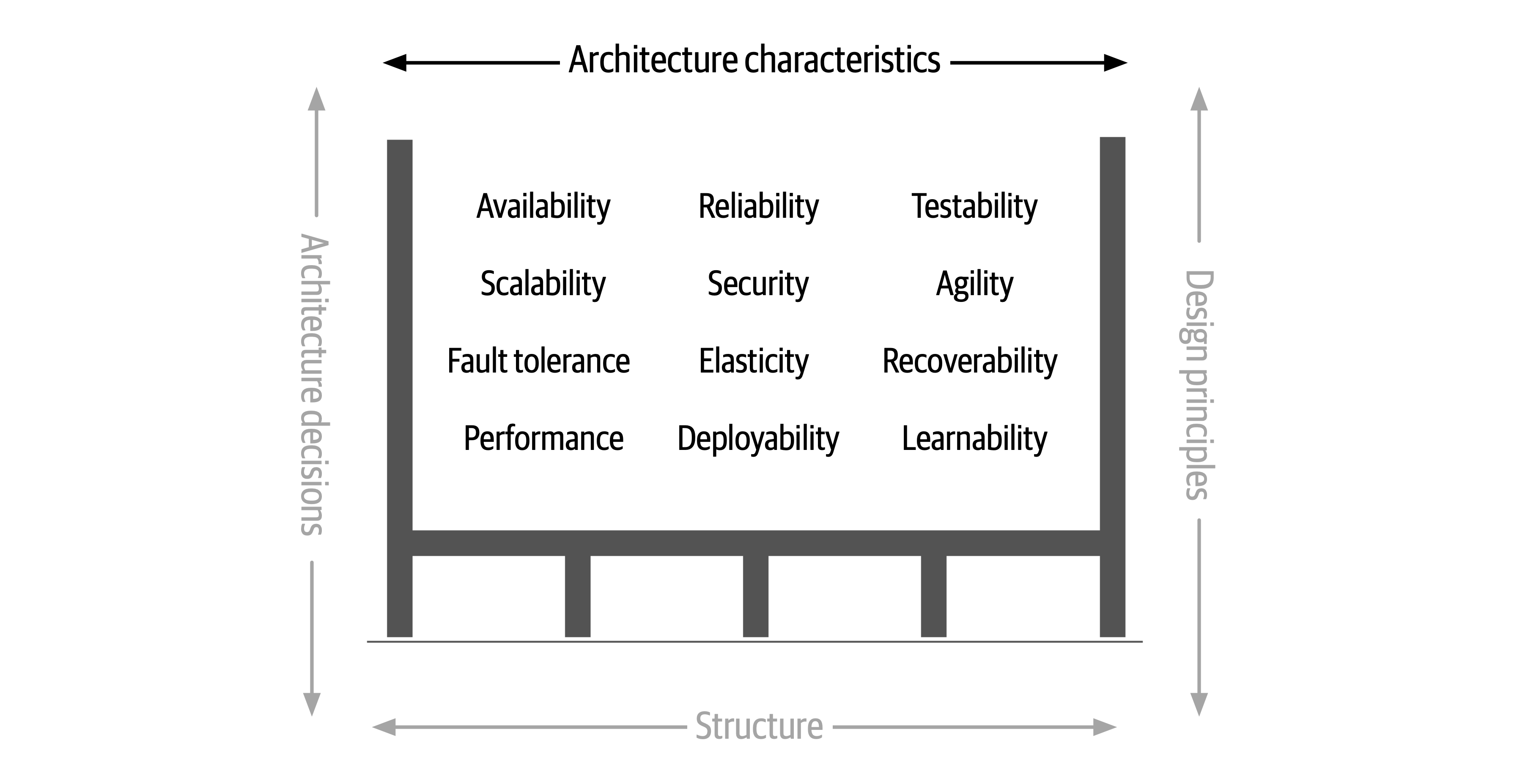

Figure 1-2. Architecture consists of the structure combined with architecture characteristics (“-ilities”), architecture decisions, and design principles

Figure 1-3. Structure refers to the type of architecture styles used in the system

Figure 1-4. Architecture characteristics refers to the “-ilities” that the system must support

The next

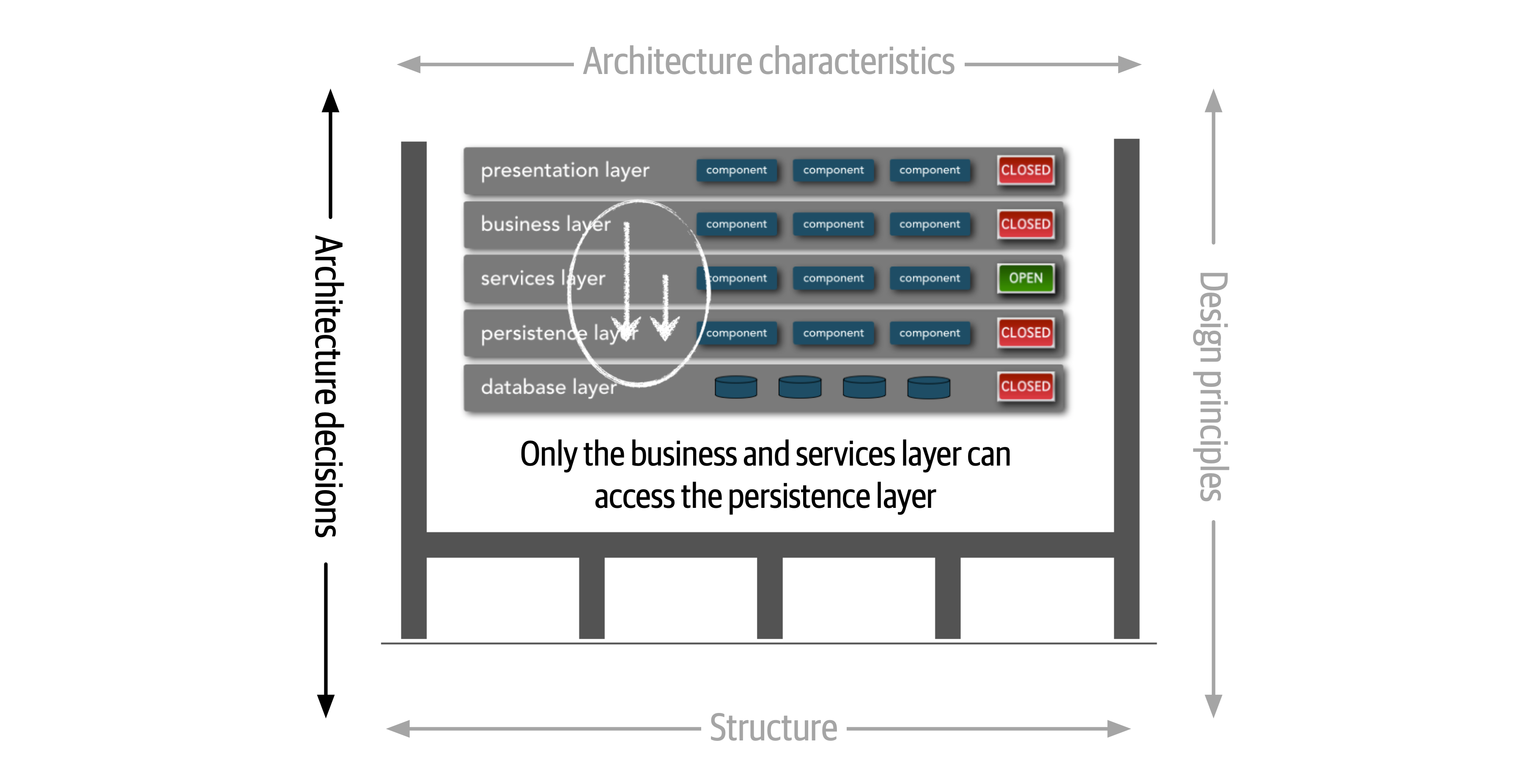

Figure 1-5. Architecture decisions are rules for constructing systems

If a particular architecture decision cannot be implemented in one part of the system due to some condition or other constraint, that decision (or rule) can be broken through something called a variance.

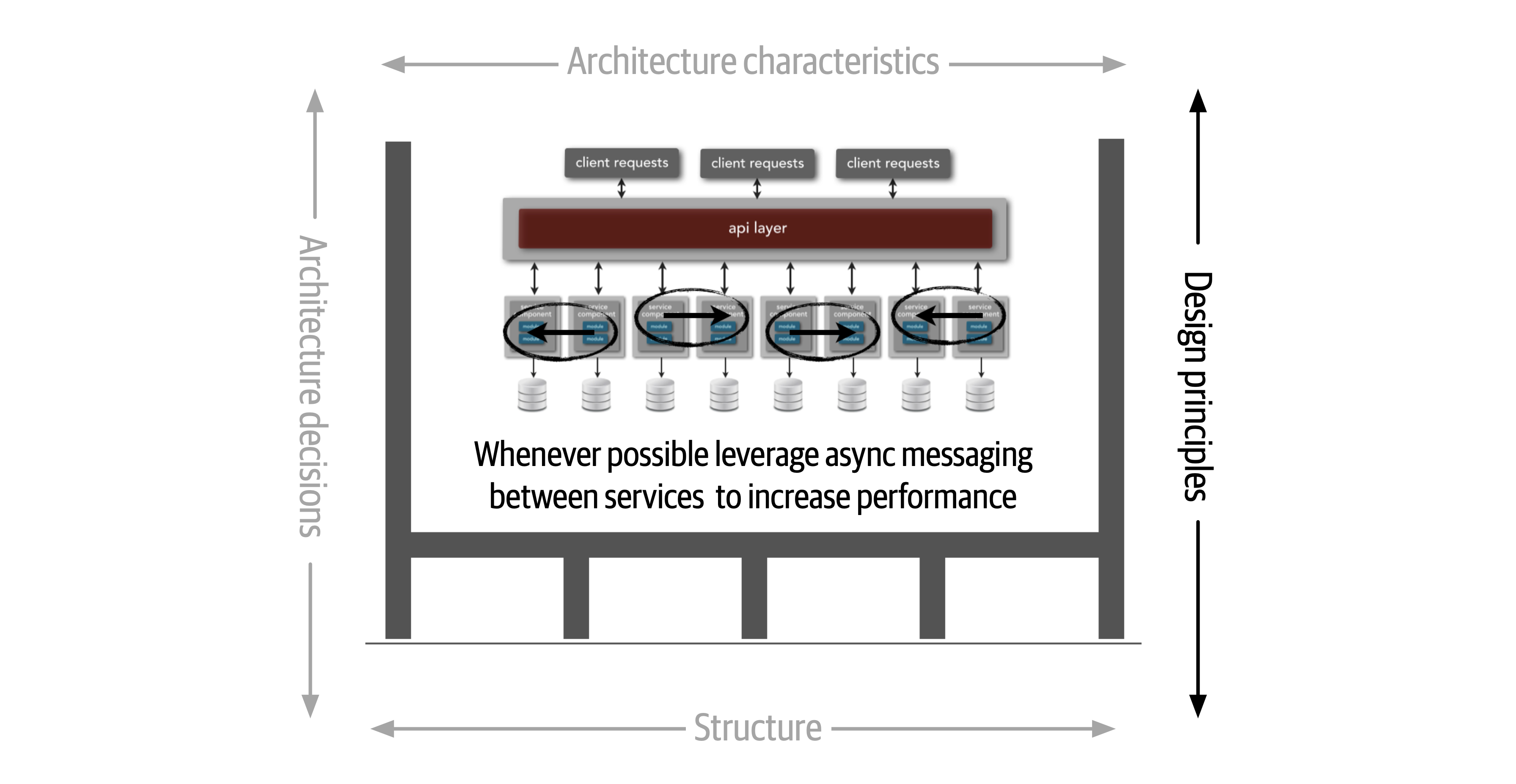

Figure 1-6. Design principles are guidelines for constructing systems

Expectations of an Architect

There are eight core expectations placed on a software architect, irrespective of any given role, title, or job description:

-

Make architecture decisions

-

Continually analyze the architecture

-

Keep current with latest trends

-

Ensure compliance with decisions

-

Diverse exposure and experience

-

Have business domain knowledge

-

Possess interpersonal skills

-

Understand and navigate politics

The first key to effectiveness and success in the software architect role depends on understanding and practicing each of these expectations.

Make Architecture Decisions

An architect is expected to define the architecture decisions and design principles used to guide technology decisions within the team, the department, or across the enterprise.

Guide is the key operative word in this first expectation. An architect should guide rather than specify technology choices. For example, an architect might make a decision to use React.js for frontend development. In this case, the architect is making a technical decision rather than an architectural decision or design principle that will help the development team make choices. An architect should instead instruct development teams to use a reactive-based framework for frontend web development, hence guiding the development team in making the choice between Angular, Elm, React.js, Vue, or any of the other reactive-based web frameworks.

Continually Analyze the Architecture

An architect is expected to continually analyze the architecture and current technology environment and then recommend solutions for improvement.

This expectation of an architect refers to architecture vitality, which assesses how viable the architecture that was defined three or more years ago is today, given changes in both business and technology.

Other forgotten aspects of this expectation that architects frequently forget are testing and release environments. Agility for code modification has obvious benefits, but if it takes teams weeks to test changes and months for releases, then architects cannot achieve agility in the overall architecture.

An architect must holistically analyze changes in technology and problem domains to determine the soundness of the architecture. While this kind of consideration rarely appears in a job posting, architects must meet this expectation to keep applications relevant.

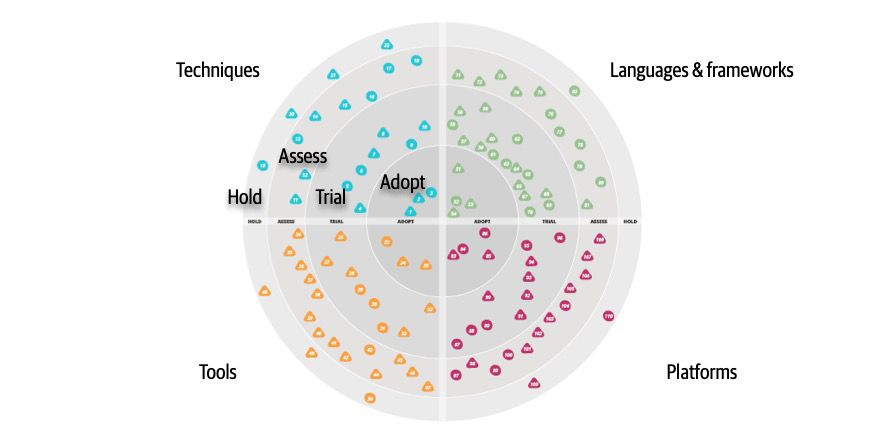

Keep Current with Latest Trends

An architect is expected to keep current with the latest technology and industry trends.

Developers must keep up to date on the latest technologies they use on a daily basis to remain relevant (and to retain a job!). An architect has an even more critical requirement to keep current on the latest technical and industry trends. The decisions an architect makes tend to be long-lasting and difficult to change. Understanding and following key trends helps the architect prepare for the future and make the correct decision.

Ensure Compliance with Decisions

An architect is expected to ensure compliance with architecture decisions and design principles.

Ensuring compliance means that the architect is continually verifying that development teams are following the architecture decisions and design principles defined, documented, and communicated by the architect. Consider the scenario where an architect makes a decision to restrict access to the database in a layered architecture to only the business and services layers (and not the presentation layer). This means that the presentation layer must go through all layers of the architecture to make even the simplest of database calls. A user interface developer might disagree with this decision and access the database (or the persistence layer) directly for performance reasons. However, the architect made that architecture decision for a specific reason: to control change. By closing the layers, database changes can be made without impacting the presentation layer. By not ensuring compliance with architecture decisions, violations like this can occur, the architecture will not meet the required architectural characteristics (“-ilities”), and the application or system will not work as expected.

In Chapter 6 we talk more about measuring compliance using automated fitness functions and automated tools.

Diverse Exposure and Experience

An architect is expected to have exposure to multiple and diverse technologies, frameworks, platforms, and environments.

This expectation does not mean an architect must be an expert in every framework, platform, and language, but rather that an architect must at least be familiar with a variety of technologies. Most environments these days are heterogeneous, and at a minimum an architect should know how to interface with multiple systems and services, irrespective of the language, platform, and technology those systems or services are written in.

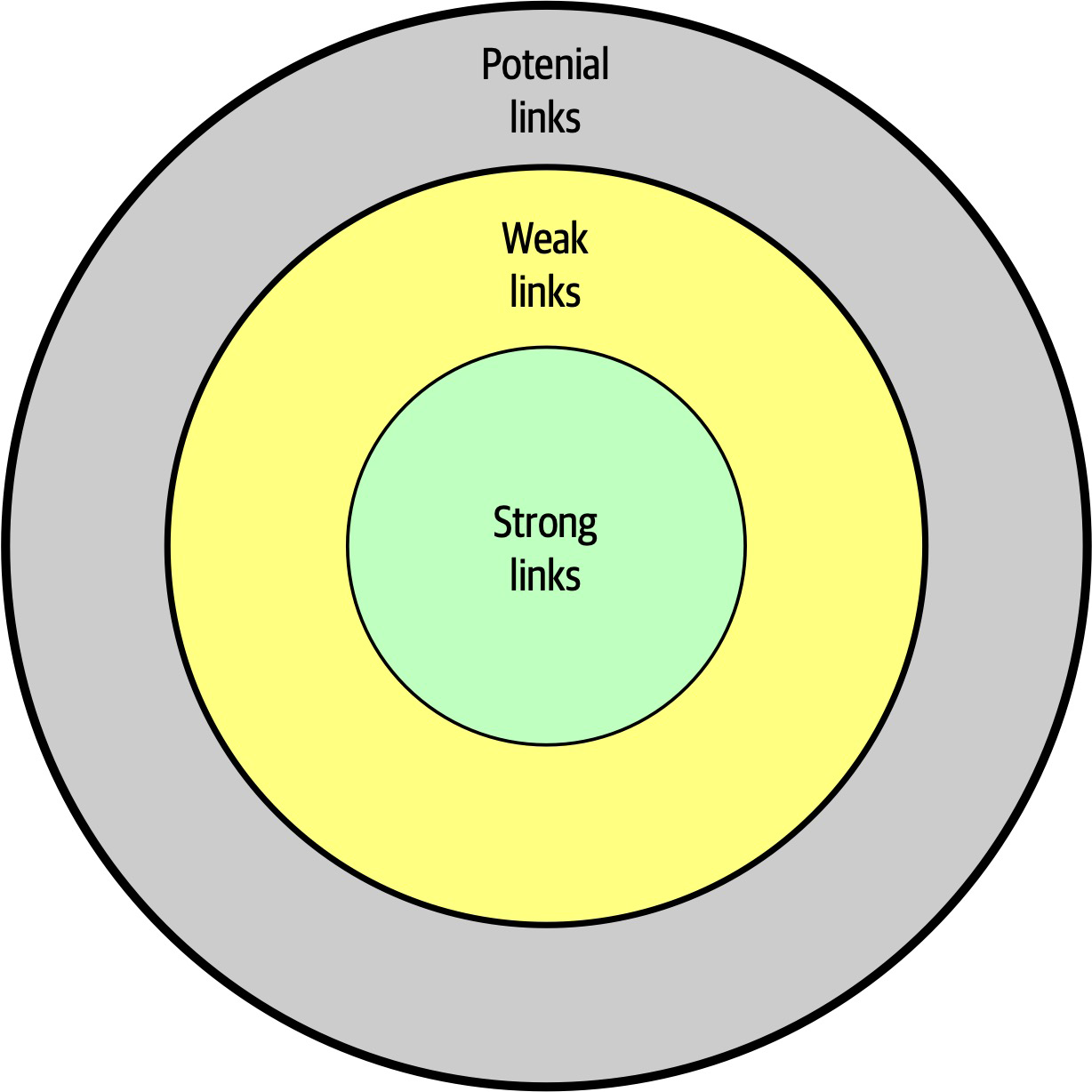

One of the best ways of mastering this expectation is for the architect to stretch their comfort zone. Focusing only on a single technology or platform is a safe haven. An effective software architect should be aggressive in seeking out opportunities to gain experience in multiple languages, platforms, and technologies. A good way of mastering this expectation is to focus on technical breadth rather than technical depth. Technical breadth includes the stuff you know about, but not at a detailed level, combined with the stuff you know a lot about. For example, it is far more valuable for an architect to be familiar with 10 different caching products and the associated pros and cons of each rather than to be an expert in only one of them.

Have Business Domain Knowledge

An architect is expected to have a certain level of business domain expertise.

Effective software architects understand not only technology but also the business domain of a problem space.

The most successful architects we know are those who have broad, hands-on technical knowledge coupled with a strong knowledge of a particular domain. These software architects are able to effectively communicate with C-level executives and business users using the domain knowledge and language that these stakeholders know and understand. This in turn creates a strong level of confidence that the software architect knows what they are doing and is competent to create an effective and correct architecture.

Possess Interpersonal Skills

An architect is expected to possess exceptional interpersonal skills, including teamwork, facilitation, and leadership.

The industry is flooded with software architects, all competing for a limited number of architecture positions. Having strong leadership and interpersonal skills is a good way for an architect to differentiate themselves from other architects and stand out from the crowd. We’ve known many software architects who are excellent technologists but are ineffective architects due to the inability to lead teams, coach and mentor developers, and effectively communicate ideas and architecture decisions and principles. Needless to say, those architects have difficulties holding a position or job.

Understand and Navigate Politics

An architect is expected to understand the political climate of the enterprise and be able to navigate the politics.

It might seem rather strange talk about negotiation and navigating office politics in

Now consider the scenario where an architect, responsible for a large customer relationship management system, is having issues controlling database access from other systems, securing certain customer data, and making any database schema change because too many other systems are using the CRM database. The architect therefore makes the decision to create what are called application silos, where each application database is only accessible from the application owning that database. Making this decision will give the architect better control over the customer data, security, and change control. However, unlike the previous developer scenario, this decision will also be challenged by almost everyone in the company (with the possible exception of the CRM application team, of course). Other applications need the customer management data. If those applications are no longer able to access the database directly, they must now ask the CRM system for the data, requiring remote access calls through REST, SOAP, or some other remote access protocol.

Intersection of Architecture and…

The following sections delve into some of the newer intersections between the role of architect and other parts of an organization, highlighting new capabilities and responsibilities for architects.

Engineering Practices

However, over the last few years, engineering advances have thrust process concerns upon software architecture. It is useful to separate software development process from engineering practices. By process, we mean how teams are formed and managed, how meetings are conducted, and workflow organization; it refers to the mechanics of how people organize and interact. Software engineering practices, on the other hand, refer to process-agnostic practices that have illustrated, repeatable benefit. For example, continuous integration is a proven engineering practice that doesn’t rely on a particular process.

Focusing on engineering practices is important. First, software development lacks many of the features of more mature engineering disciplines. For example, civil engineers can predict structural change with much more accuracy than similarly important aspects of software structure. Second, one of the Achilles heels of software development is estimation—how much time, how many resources, how much money? Part of this difficulty lies with antiquated accounting practices that cannot accommodate the exploratory nature of software development, but another part is because we’re traditionally bad at estimation, at least in part because of unknown unknowns.

…because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don’t know we don’t know.Former United States Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld

Unknown unknowns are the nemesis of software systems. Many projects start with a list of known unknowns: things developers must learn about the domain and technology they know are upcoming. However, projects also fall victim to unknown unknowns: things no one knew were going to crop up yet have appeared unexpectedly. This is why all “Big Design Up Front” software efforts suffer: architects cannot design for unknown unknowns. To quote Mark (one of your authors):

All architectures become iterative because of unknown unknowns, Agile just recognizes this and does it sooner.

Thus, while process is mostly separate from architecture, an iterative process fits the nature of software architecture better. Teams trying to build a modern system such as microservices using an antiquated process like Waterfall will find a great deal of friction from an antiquated process that ignores the reality of how software comes together.

Often, the architect is also the technical leader on projects and therefore determines the engineering practices the team uses. Just as architects must carefully consider the problem domain before choosing an architecture, they must also ensure that the architectural style and engineering practices form a symbiotic mesh. For example, a microservices architecture assumes automated machine provisioning, automated testing and deployment, and a raft of other assumptions. Trying to build one of these architectures with an antiquated operations group, manual processes, and little testing creates tremendous friction and challenges to success. Just as different problem domains lend themselves toward certain architectural styles, engineering practices have the same kind of symbiotic relationship.

Figure 1-7. The architecture for a software system consists of both requirements and all the other architectural characteristics

As any experience in the software development world illustrates, nothing remains static. Thus, architects may design a system to meet certain criteria, but that design must survive both implementation (how can architects make sure that their design is implemented correctly) and the inevitable change driven by the software development ecosystem. What we need is an evolutionary architecture.

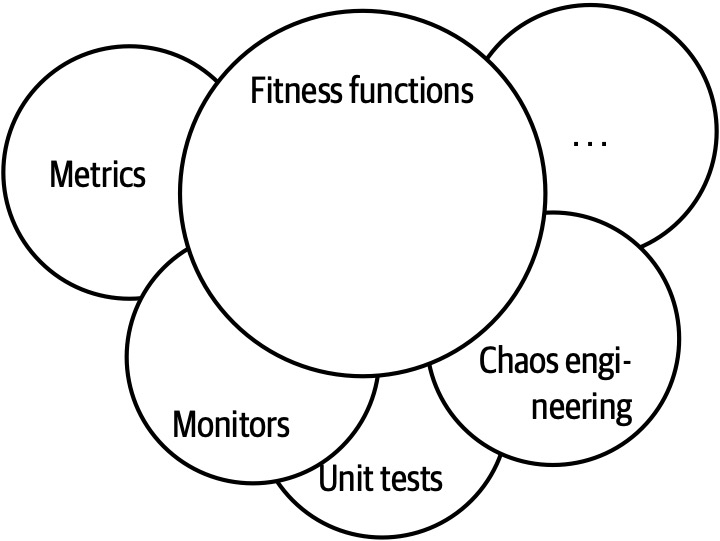

Building Evolutionary Architectures introduces the concept of using fitness functions to protect (and govern) architectural characteristics as change occurs over time.

We won’t go into the full details of fitness functions here. However, we will point out opportunities and examples of the approach where applicable. Note the correlation between how often fitness functions execute and the feedback they provide. You’ll see that adopting Agile engineering practices such as continuous integration, automated machine provisioning, and similar practices makes building resilient architectures easier. It also illustrates how intertwined architecture has become with engineering practices.

Operations/DevOps

However, a few years ago, several companies started experimenting with new forms of architecture that combine many operational concerns with the architecture. For example, in older-style architectures, such as ESB-driven SOA, the architecture was designed to handle things like elastic scale, greatly complicating the architecture in the process. Basically, architects were forced to defensively design around the limitations introduced because of the cost-saving measure of outsourcing operations. Thus, they built architectures that could handle scale, performance, elasticity, and a host of other capabilities internally. The side effect of that design was vastly more complex architecture.

The builders of the microservices style of architecture realized that these operational concerns are better handled by operations.

Process

Another axiom is that software architecture is mostly orthogonal to the software development process; the way that you build software (process) has little impact on the software architecture (structure).

As the previous quote from Mark observes, all architecture becomes iterative; it’s only a matter of time. Toward that end, we’re going assume a baseline of Agile methodologies throughout and call out exceptions where appropriate. For example, it is still common for many monolithic architectures to use older processes because of their age, politics, or other mitigating factors unrelated to software.

Data

A large percentage of serious application development includes external data storage, often in the form of a relational (or, increasingly, NoSQL) database. However, many

Laws of Software Architecture

While the scope of software architecture is almost impossibly broad, unifying elements do exist.

Everything in software architecture is a trade-off.

First Law of Software Architecture

Nothing exists on a nice, clean spectrum for software architects. Every decision must take into account many opposing factors.

If an architect thinks they have discovered something that isn’t a trade-off, more likely they just haven’t identified the trade-off yet.

Corollary 1

Why is more important than how.

Second Law of Software Architecture

The authors discovered the importance of this perspective when we tried keeping the results of exercises done by students during workshop as they crafted architecture solutions. Because the exercises were timed, the only artifacts we kept were the diagrams representing the topology. In other words, we captured how they solved the problem but not why the team made particular choices. An architect can look at an existing system they have no knowledge of and ascertain how the structure of the architecture works, but will struggle explaining why certain choices were made versus others.

Part I. Foundations

To understand important trade-offs in architecture, developers must understand some basic concepts and terminology concerning components, modularity, coupling, and connascence.

Chapter 2. Architectural Thinking

An architect sees things differently from a developer’s point of view, much in the same way a meteorologist might see clouds differently from an artist’s point of view.

Figure 2-1. Architectural thinking (iStockPhoto)

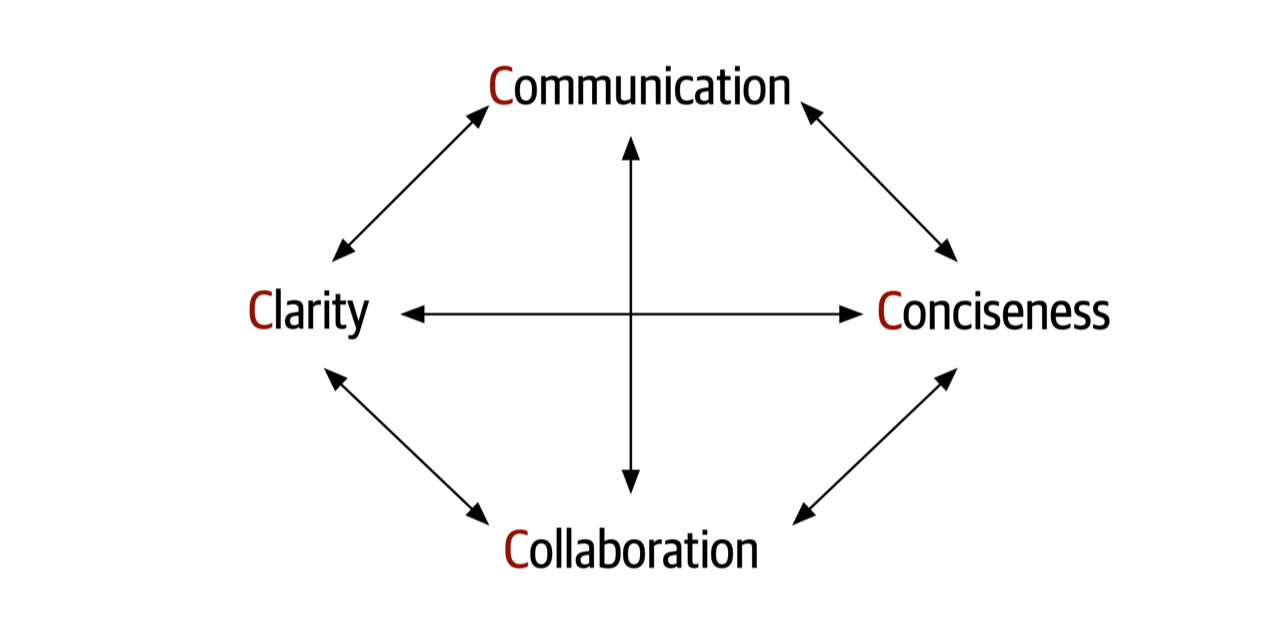

Architectural thinking is much more than that. It is seeing things with an architectural eye, or an architectural point of view. There are four main aspects of thinking like an architect. First, it’s understanding the difference between architecture and design and knowing how to collaborate with development teams to make architecture work. Second, it’s about having a wide breadth of technical knowledge while still maintaining a certain level of technical depth, allowing the architect to see solutions and possibilities that others do not see. Third, it’s about understanding, analyzing, and reconciling trade-offs between various solutions and technologies. Finally, it’s about understanding the importance of business drivers and how they translate to architectural concerns.

In this chapter we explore these four aspects of thinking like an architect and seeing things with an architectural eye.

Architecture Versus Design

The difference between architecture and design is often a confusing one. Where does architecture end and design begin?

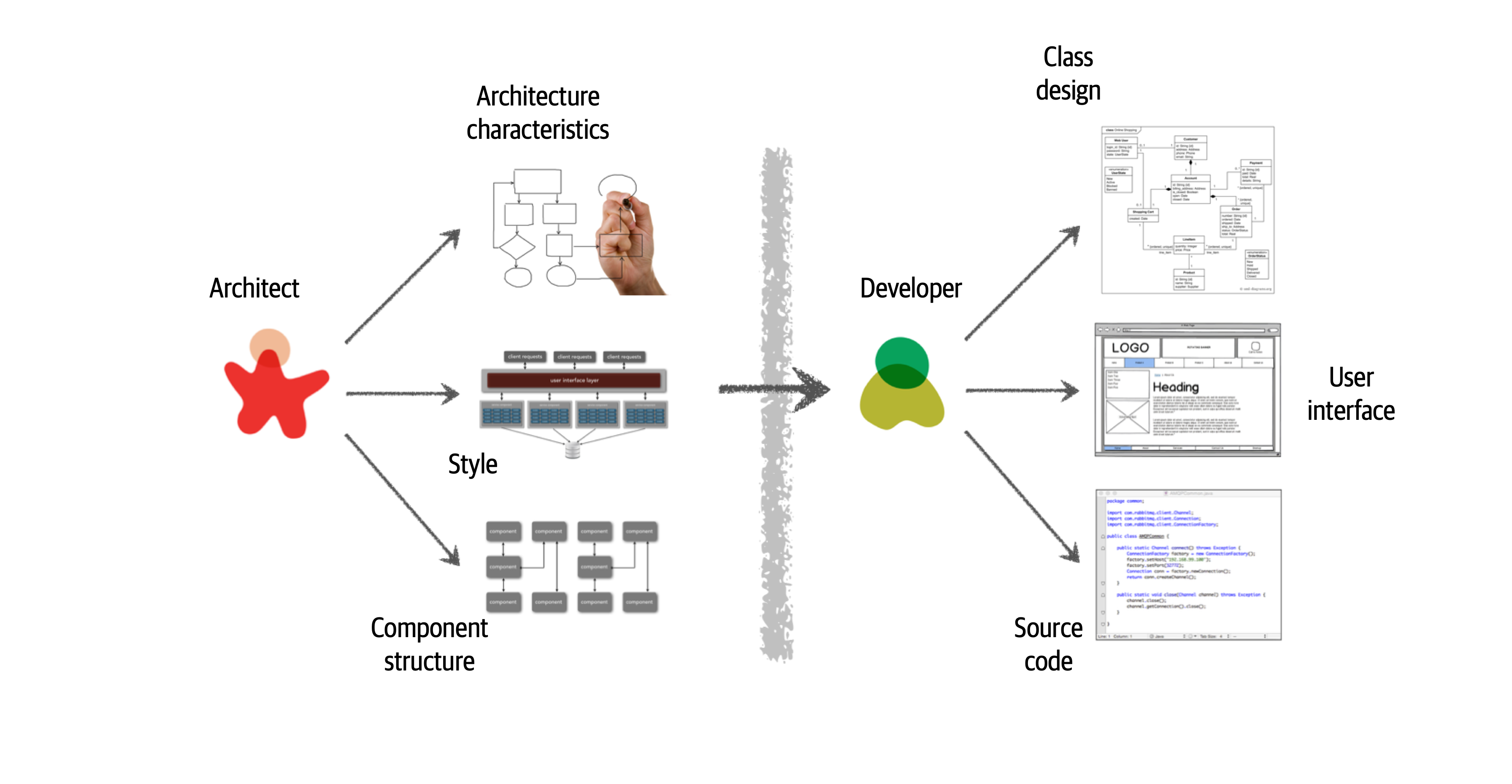

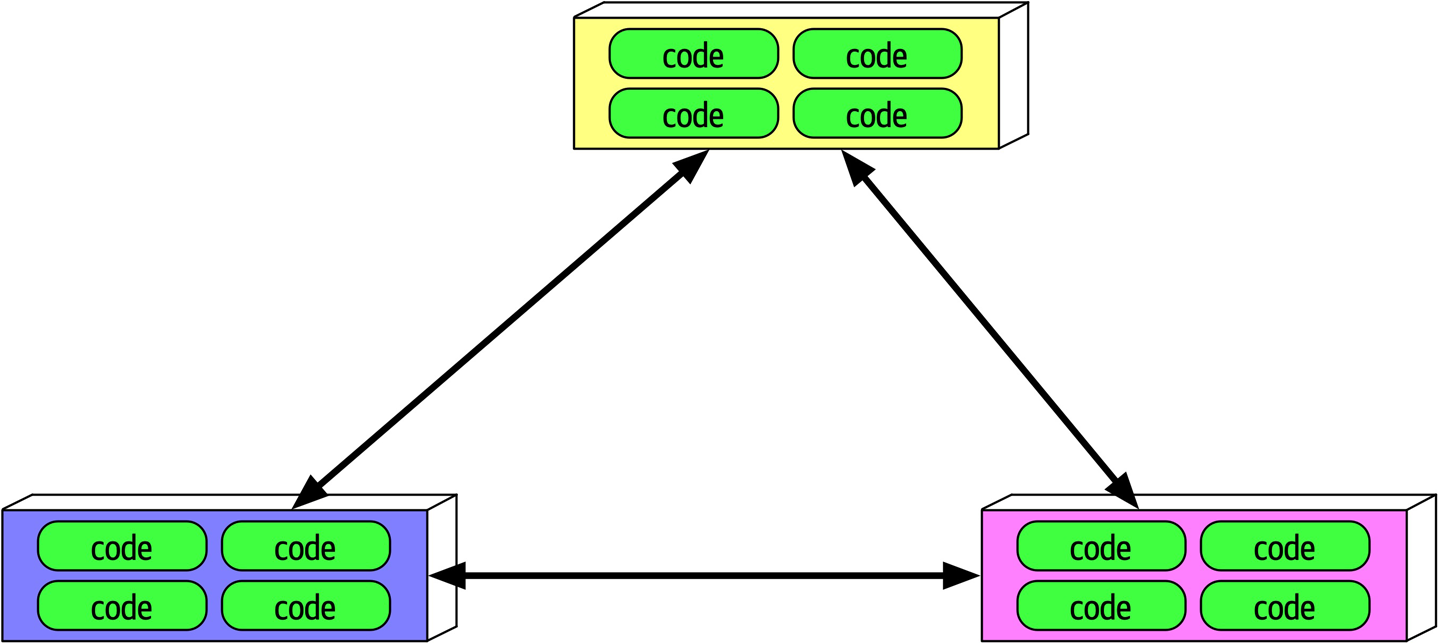

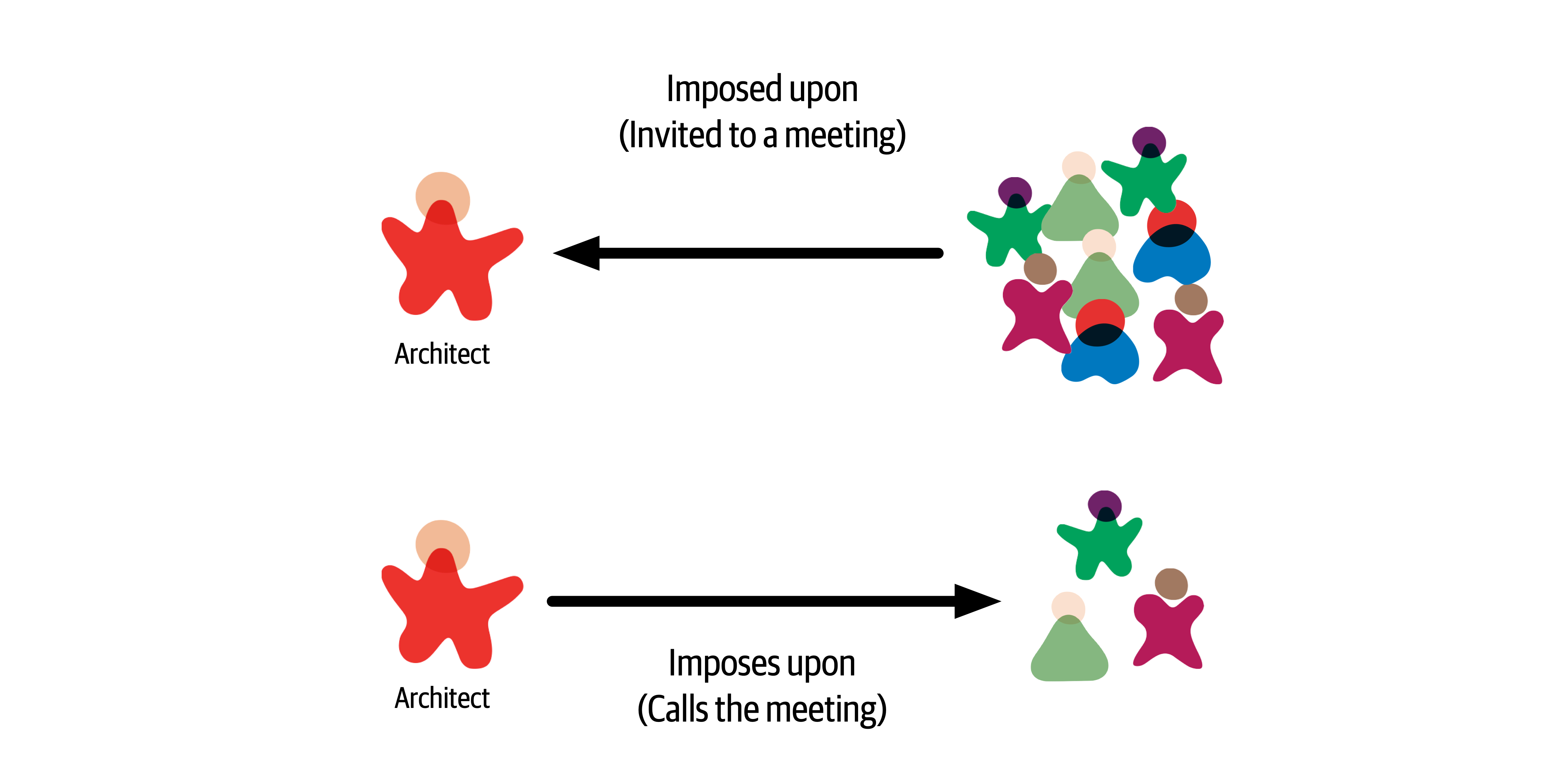

Figure 2-2. Traditional view of architecture versus design

There are several issues with the traditional responsibility model illustrated in Figure 2-2. As a matter of fact, this illustration shows exactly why architecture rarely works. Specifically, it is the unidirectional arrow passing though the virtual and physical barriers separating the architect from the developer that causes all of the problems associated with architecture. Decisions an architect makes sometimes never make it to the development teams, and decisions development teams make that change the architecture rarely get back to the architect. In this model the architect is disconnected from the development teams, and as such the architecture rarely provides what it was originally set out to do.

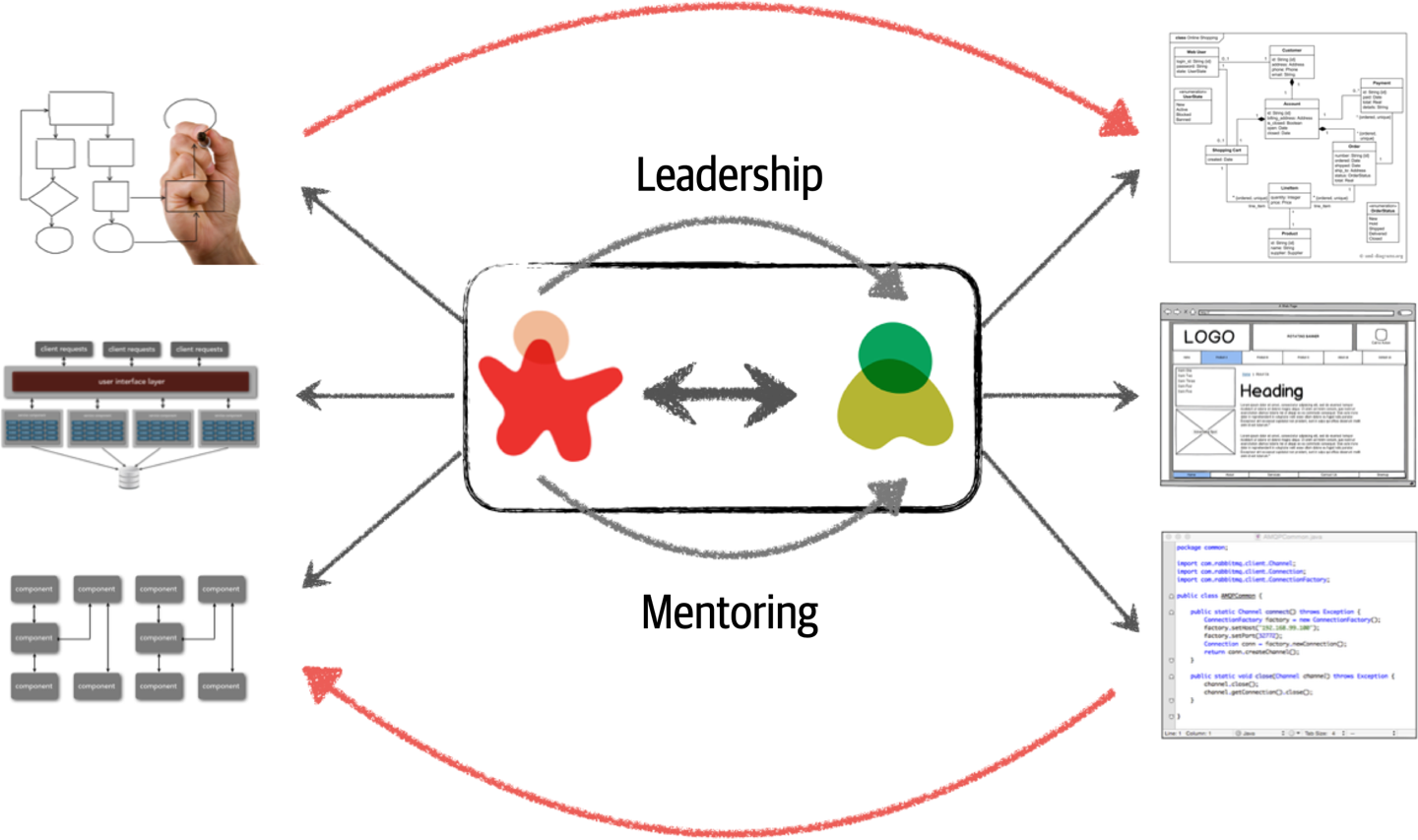

To make architecture work, both the physical and virtual barriers that exist between architects and developers must be broken down, thus forming a strong bidirectional relationship between architects and development teams. The architect and developer must be on the same virtual team to make this work, as depicted in Figure 2-3. Not only does this model facilitate strong bidirectional communication between architecture and development, but it also allows the architect to provide mentoring and coaching to developers on the team.

Figure 2-3. Making architecture work through collaboration

Unlike the old-school waterfall approaches to static and rigid software architecture, the architecture of today’s systems changes and evolves every iteration or phase of a project. A tight collaboration between the architect and the development team is essential for the success of any software project. So where does architecture end and design begin? It doesn’t. They are both part of the circle of life within a software project and must always be kept in synchronization

Technical Breadth

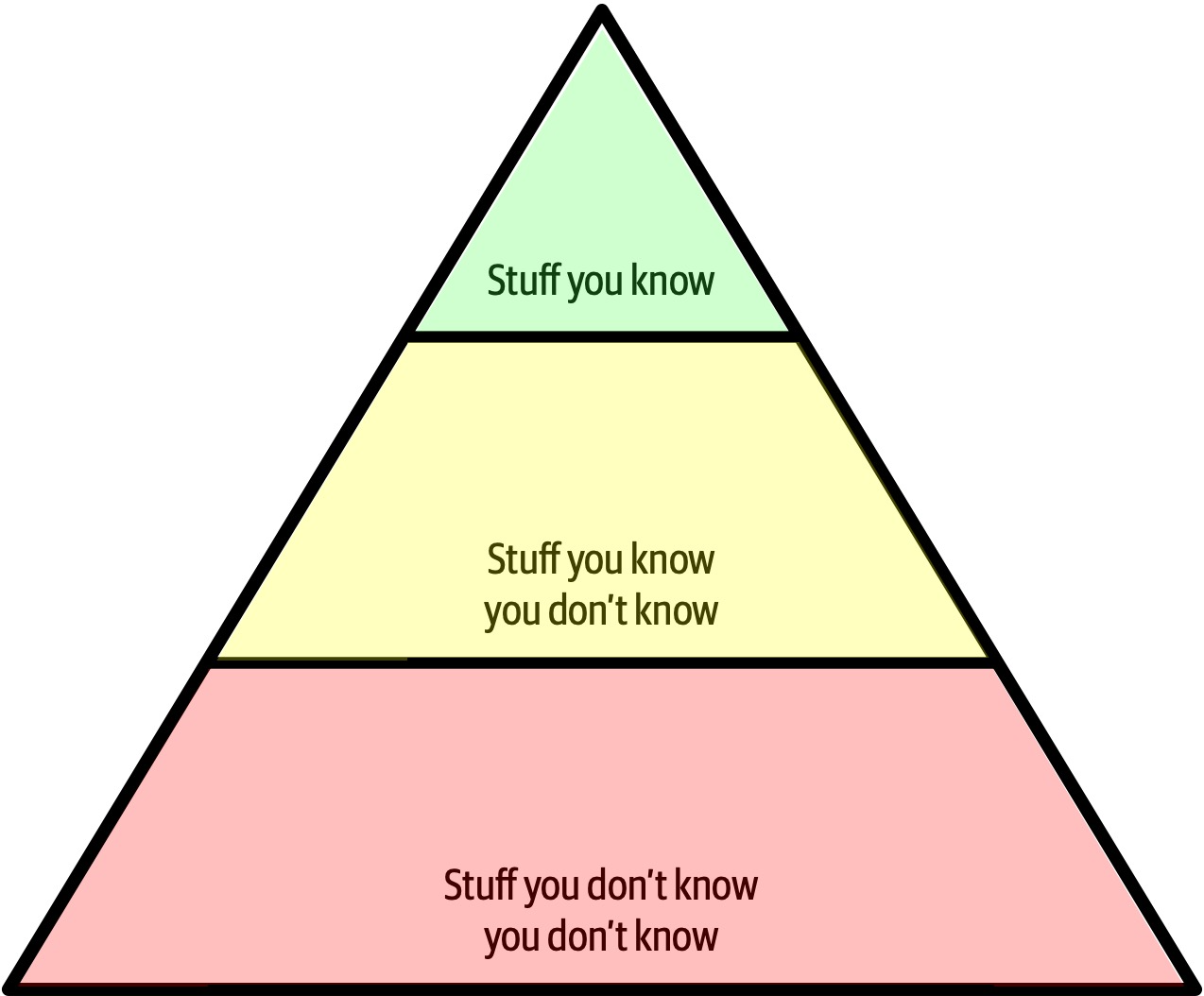

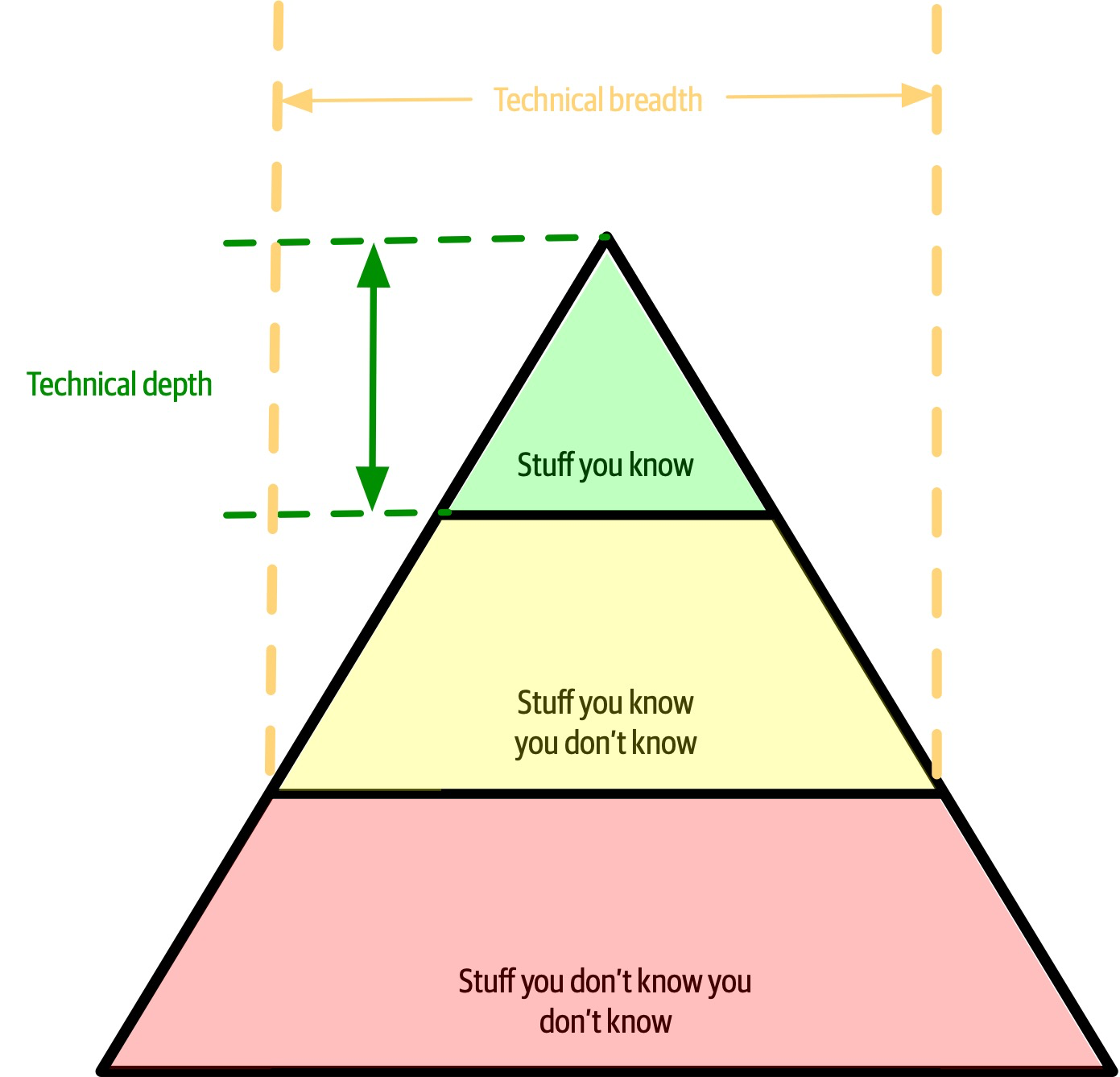

Figure 2-4. The pyramid representing all knowledge

As shown in Figure 2-4, any individual can partition all their knowledge into three sections: stuff you know, stuff you know you don’t know, and stuff you don’t know you don’t know.

Stuff you know includes the technologies, frameworks, languages, and tools a technologist uses on a daily basis to perform their job, such as knowing Java as a Java programmer. Stuff you know you don’t know includes those things a technologist knows a little about or has heard of but has little or no expertise in. A good example of this level of knowledge is the Clojure programming language. Most technologists have heard of Clojure and know it’s a programming language based on Lisp, but they can’t code in the language. Stuff you don’t know you don’t know is the largest part of the knowledge triangle and includes the entire host of technologies, tools, frameworks, and languages that would be the perfect solution to a problem a technologist is trying to solve, but the technologist doesn’t even know those things exist.

A developer’s early career focuses on expanding the top of the pyramid, to build experience and expertise. This is the ideal focus early on, because developers need more perspective, working knowledge, and hands-on experience. Expanding the top incidentally expands the middle section; as developers encounter more technologies and related artifacts, it adds to their stock of stuff you know you don’t know.

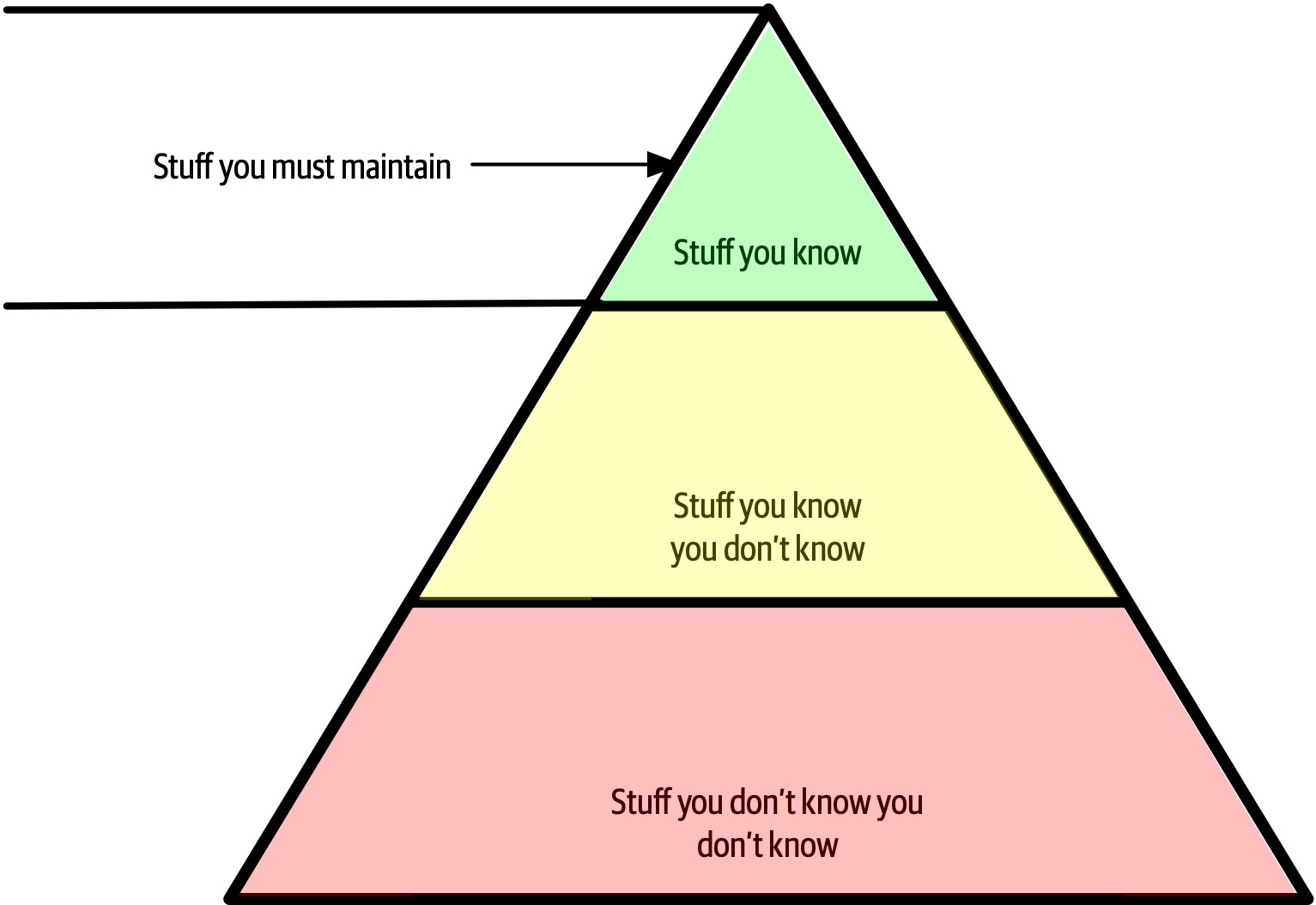

In Figure 2-5, expanding the top of the pyramid is beneficial because expertise is valued. However, the stuff you know is also the stuff you must maintain—nothing is static in the software world. If a developer becomes an expert in Ruby on Rails, that expertise won’t last if they ignore Ruby on Rails for a year or two. The things at the top of the pyramid require time investment to maintain expertise. Ultimately, the size of the top of an individual’s pyramid is their technical depth.

Figure 2-5. Developers must maintain expertise to retain it

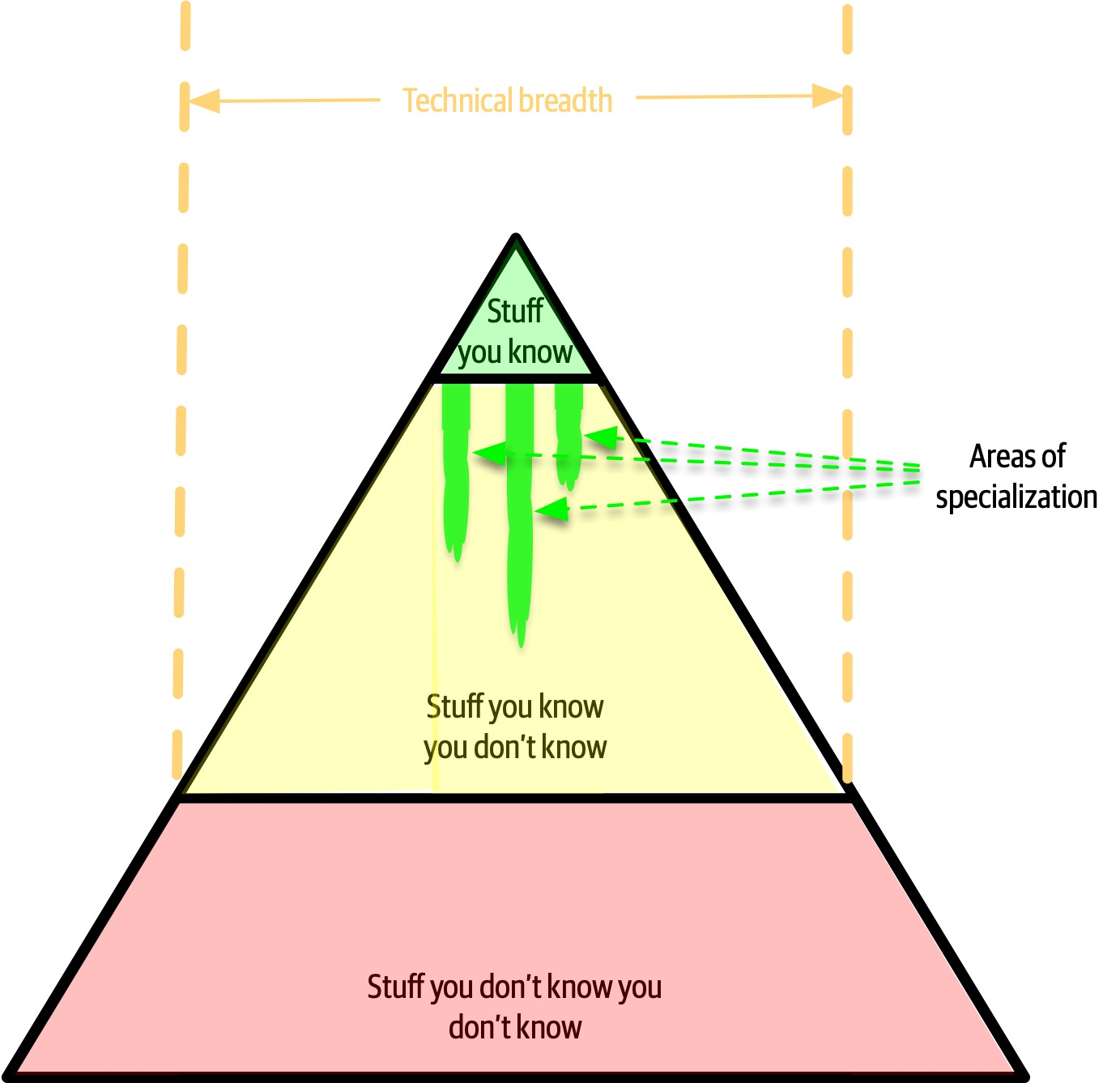

However, the nature of knowledge changes as developers transition into the architect role. A large part of the value of an architect is a broad understanding of technology and how to use it to solve particular problems. For example, as an architect, it is more beneficial to know that five solutions exist for a particular problem than to have singular expertise in only one. The most important parts of the pyramid for architects are the top and middle sections; how far the middle section penetrates into the bottom section represents an architect’s technical breadth, as shown in Figure 2-6.

Figure 2-6. What someone knows is technical depth, and how much someone knows is technical breadth

As an architect, breadth is more important than depth. Because architects must make decisions that match capabilities to technical constraints, a broad understanding of a wide variety of solutions is valuable. Thus, for an architect, the wise course of action is to sacrifice some hard-won expertise and use that time to broaden their portfolio, as shown in Figure 2-7. As illustrated in the diagram, some areas of expertise will remain, probably in particularly enjoyable technology areas, while others usefully atrophy.

Figure 2-7. Enhanced breadth and shrinking depth for the architect role

Our knowledge pyramid illustrates how fundamentally different the role of architect compares to developer. Developers spend their whole careers honing expertise, and transitioning to the architect role means a shift in that perspective, which many individuals find difficult. This in turn leads to two common dysfunctions: first, an architect tries to maintain expertise in a wide variety of areas, succeeding in none of them and working themselves ragged in the process. Second, it manifests as stale expertise—the mistaken sensation that your outdated information is still cutting edge. We see this often in large companies where the developers who founded the company have moved into leadership roles yet still make technology decisions using ancient criteria (see “Frozen Caveman Anti-Pattern”).

Architects should focus on technical breadth so that they have a larger quiver from which to draw arrows. Developers transitioning to the architect role may have to change the way they view knowledge acquisition. Balancing their portfolio of knowledge regarding depth versus breadth is something every developer should consider throughout their career.

Analyzing Trade-Offs

Architecture is the stuff you can’t Google.

There are no right or wrong answers in architecture—only trade-offs.

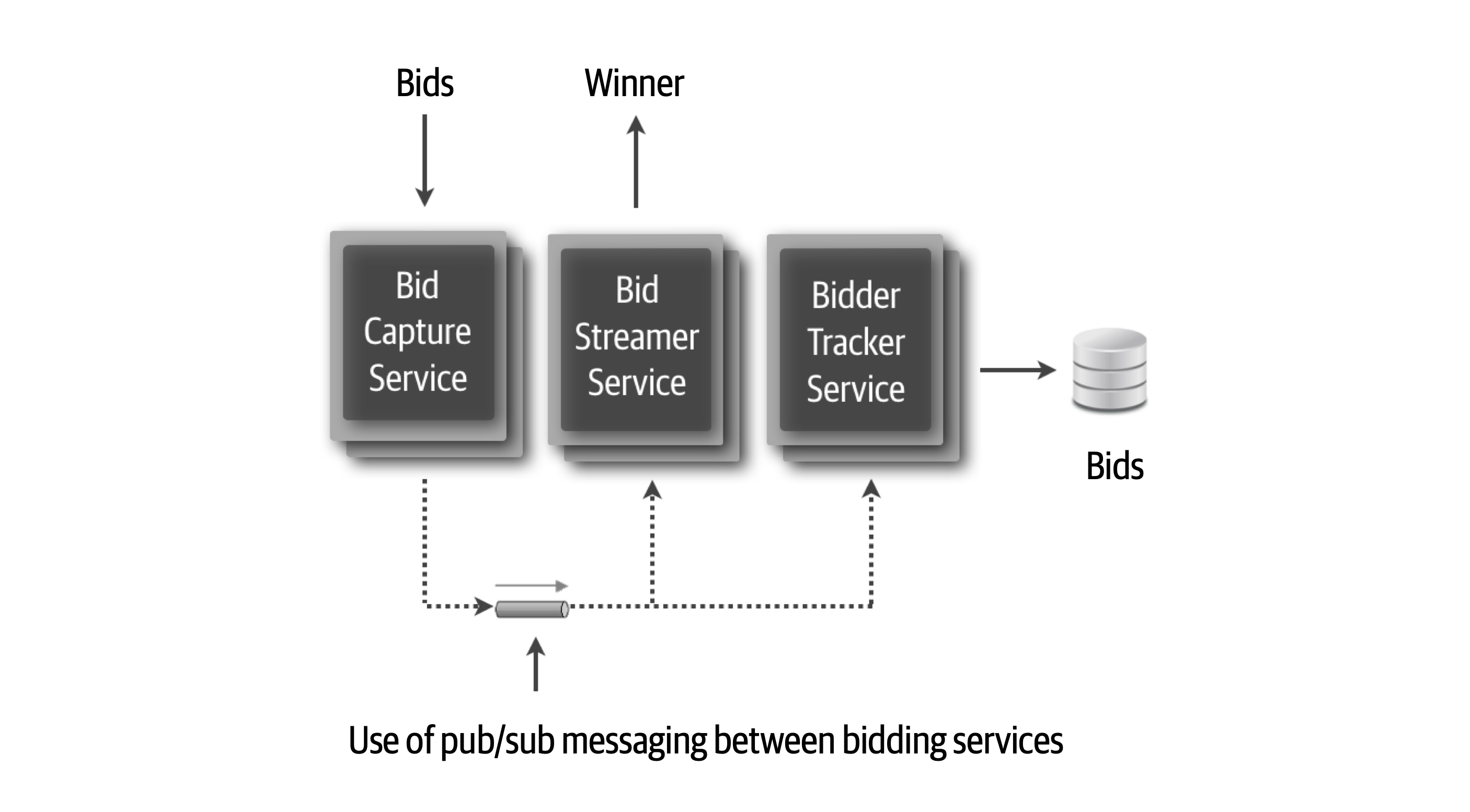

Figure 2-8. Auction system example of a trade-off—queues or topics?

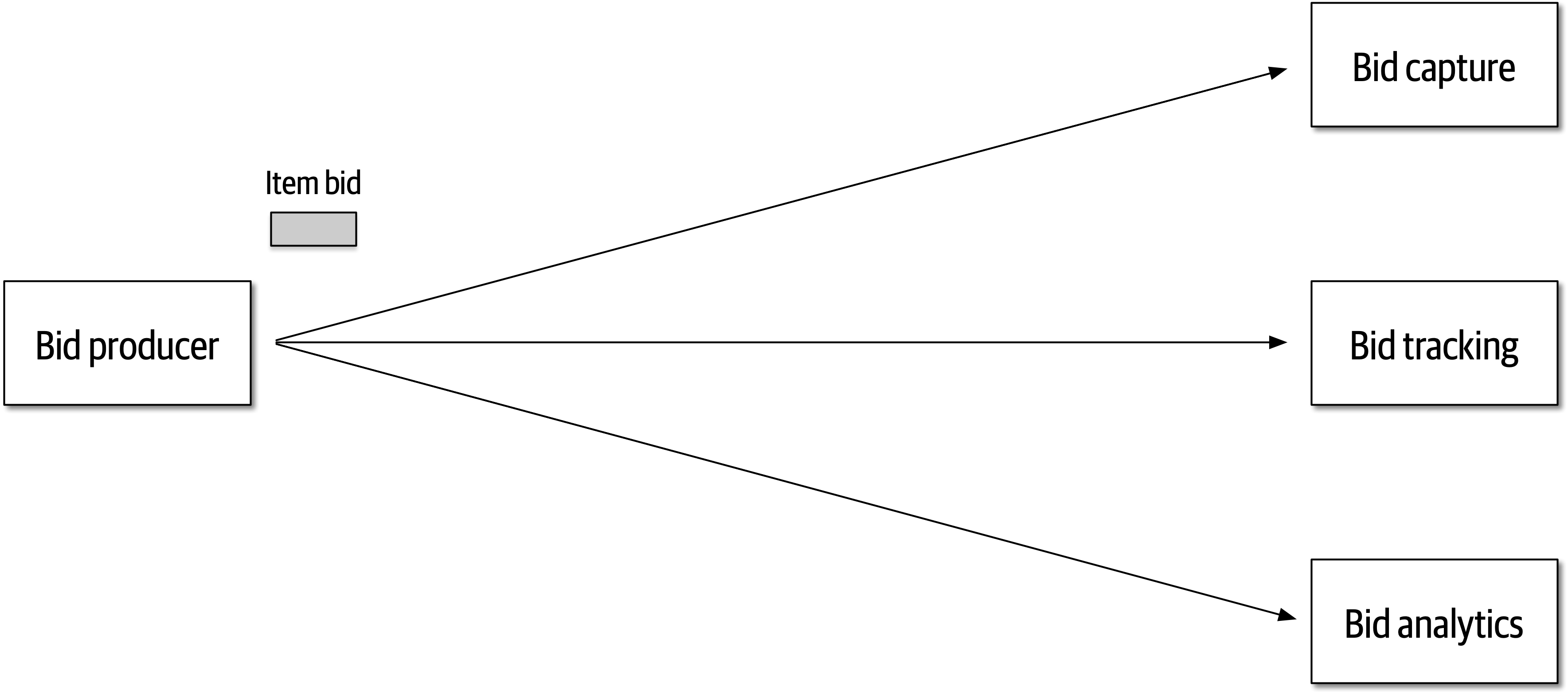

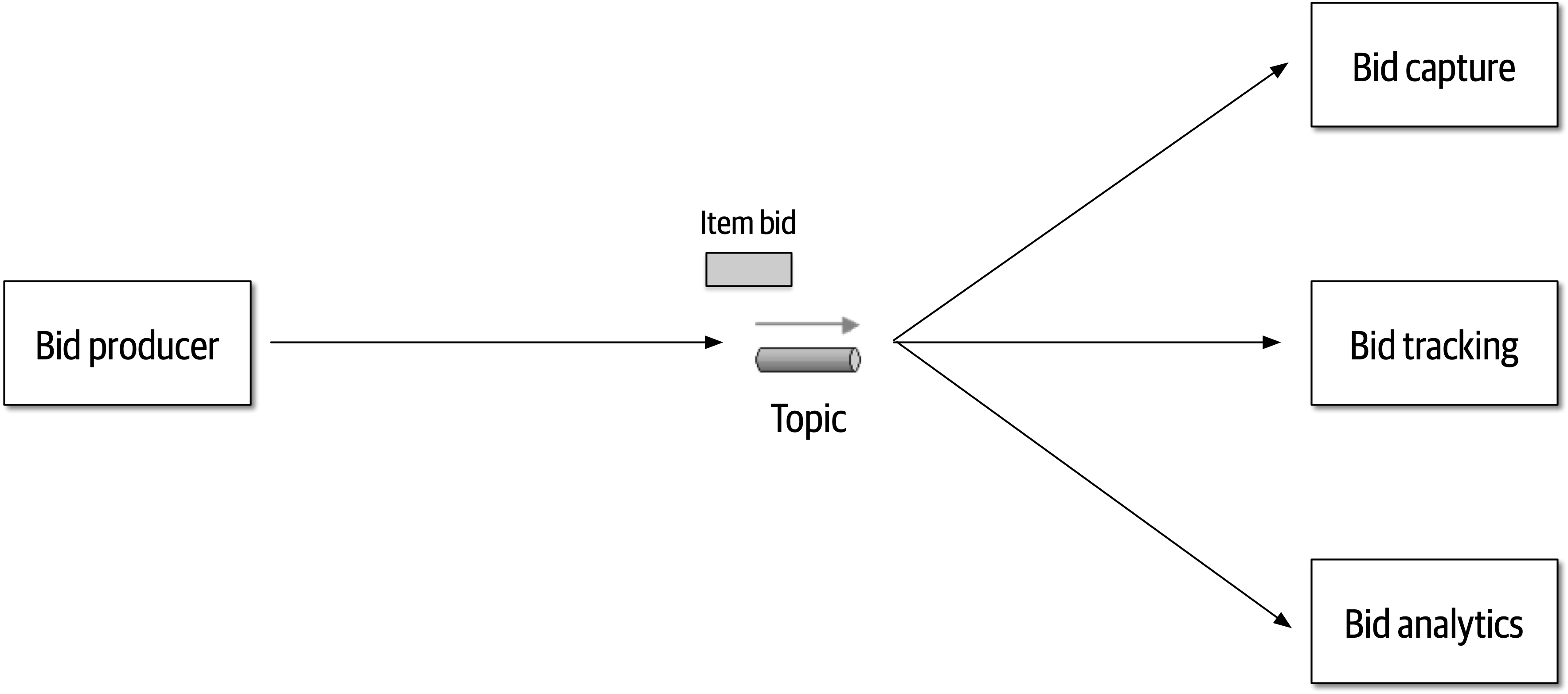

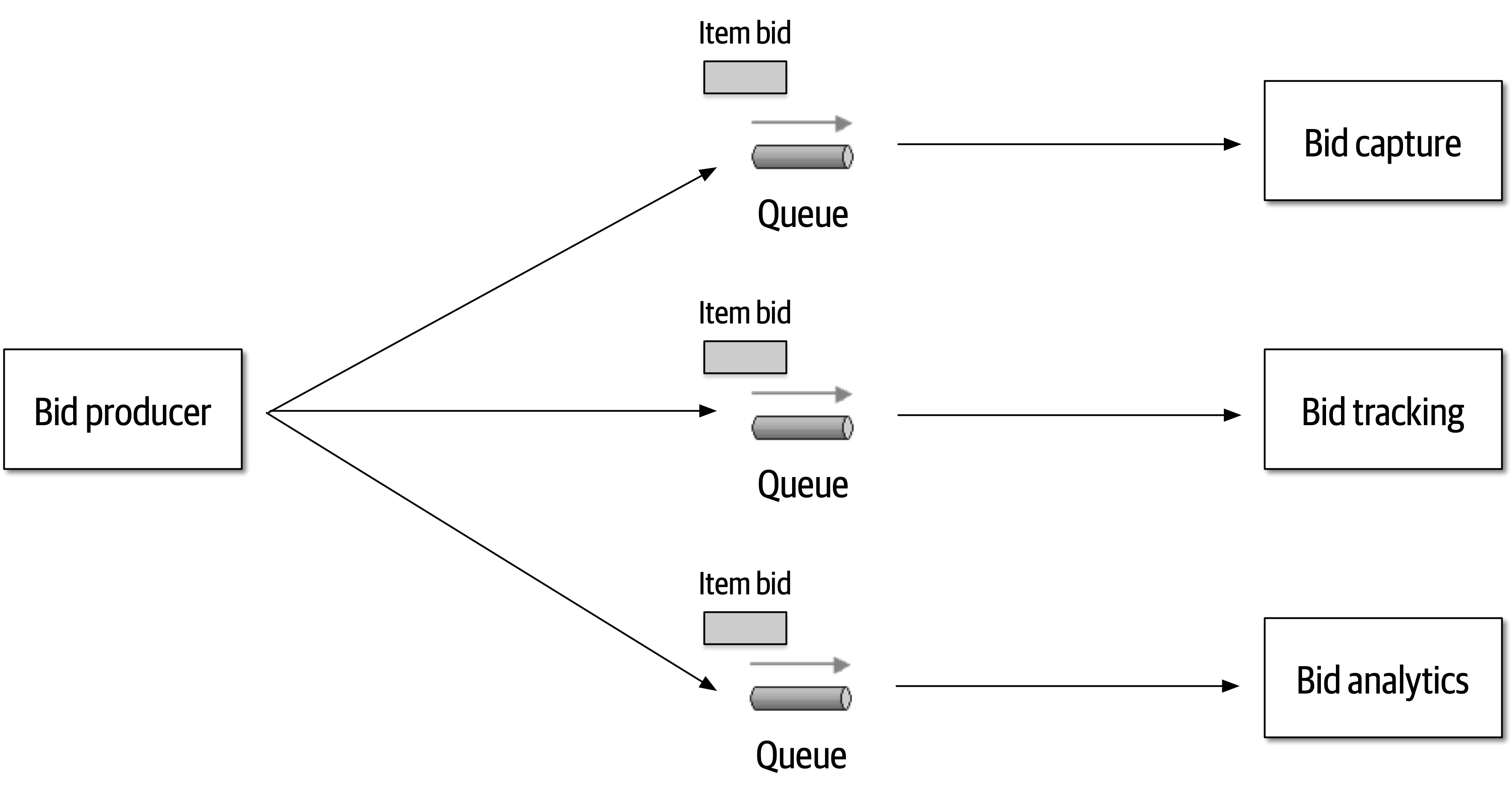

The Bid Producer service generates a bid from the bidder and then sends that bid amount to the Bid Capture, Bid Tracking, and Bid Analytics services. This could be done by using queues in a point-to-point messaging fashion or by using a topic in a publish-and-subscribe messaging fashion. Which one should the architect use? You can’t Google the answer. Architectural thinking requires the architect to analyze the trade-offs associated with each option and select the best one given the specific situation.

Figure 2-9. Use of a topic for communication between services

Figure 2-10. Use of queues for communication between services

The clear advantage (and seemingly obvious solution) to this problem in Figure 2-9 is that of architectural extensibility. The Bid Producer service only requires a single connection to a topic, unlike the queue solution in Figure 2-10 where the Bid Producer needs to connect to three different queues.

Bid History were to be added to this system due to the requirement to provide each bidder with a history of all the bids they made in each auction, no changes at all would be needed to the existing system. When the new Bid History service is created, it could simply subscribe to the topic already containing the bid information. In the queue option shown in Bid History service, and the Bid Producer would need to be modified to add an additional connection to the new queue. The point here is that using queues requires significant change to the system when adding new bidding functionality, whereas with the topic approach no changes are needed at all in the existing infrastructure. Also, notice that the Bid Producer is more decoupled in the topic option—the Bid Producer doesn’t know how the bidding information will be used or by which services. In the queue option the Bid Producer knows exactly how the bidding information is used (and by whom), and hence is more coupled to the system. With this analysis it seems clear that the topic approach using the publish-and-subscribe

Programmers know the benefits of everything and the trade-offs of nothing. Architects need to understand both.

In addition to the security issue, the topic solution in Figure 2-9 only supports homogeneous contracts. All services receiving the bidding data must accept the same contract and set of bidding data. In the queue option in Figure 2-10, each consumer can have its own contract specific to the data it needs. For example, suppose the new Bid History service requires the current asking price along with the bid, but no other service needs that information. In this case, the contract would need to be modified, impacting all other services using that data. In the queue model, this would be a separate channel, hence a separate contract not impacting any other service.

Another disadvantage of the topic model illustrated in Figure 2-9 is that it does not support monitoring of the number of messages in the topic and hence auto-scaling capabilities. However, with the queue option in Figure 2-10, each queue can be monitored individually, and programmatic load balancing applied to each bidding consumer so that each can be automatically scaled independency from one another. Note that this trade-off is technology specific in that the Advanced Message Queuing Protocol (AMQP) can support programmatic load balancing and monitoring because of the separation between an exchange (what the producer sends to) and a queue (what the consumer listens to).

| Topic advantages | Topic disadvantages |

|---|---|

Architectural extensibility | Data access and data security concerns |

Service decoupling | No heterogeneous contracts |

Monitoring and programmatic scalability |

The point here is that everything in software architecture has a trade-off: an advantage and disadvantage. Thinking like an architect is analyzing these trade-offs, then asking “which is more important: extensibility or security?” The decision between different solutions will always depend on the business drivers, environment, and a host of other factors.

Understanding Business Drivers

Thinking like an architect is understanding the business drivers that are required for the success of the system and translating those requirements into architecture characteristics (such as scalability, performance, and availability).

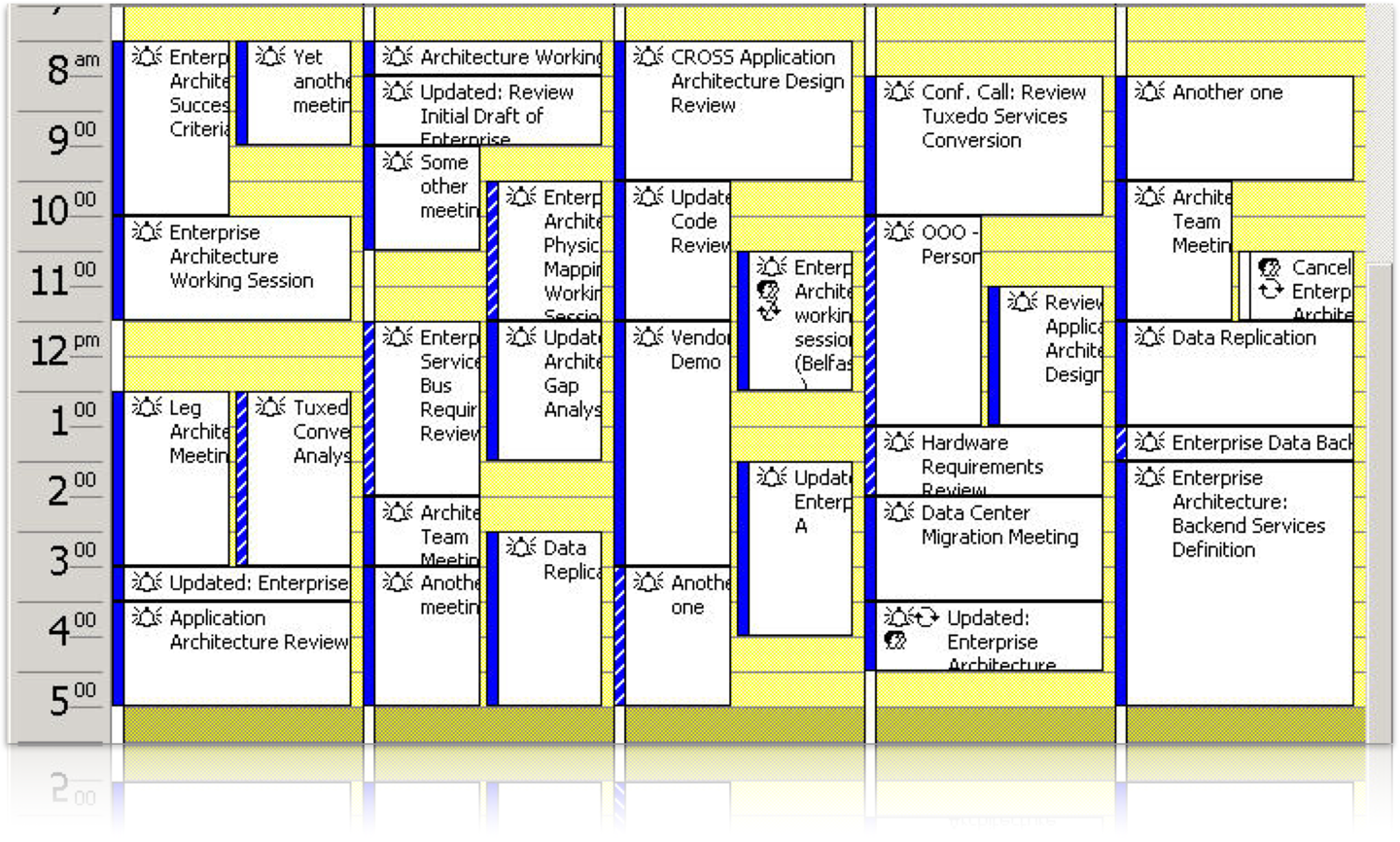

Balancing Architecture and Hands-On Coding

One of the difficult tasks an architect faces is how to balance hands-on coding with software architecture.

The first tip in striving for a balance between hands-on coding and being a software

One way to avoid the bottleneck trap as an effective software architect is to delegate the critical path and framework code to others on the development team and then focus on coding a piece of business functionality (a service or a screen) one to three iterations down the road. Three positive things happen by doing this. First, the architect is gaining hands-on experience writing production code while no longer becoming a bottleneck on the team. Second, the critical path and framework code is distributed to the development team (where it belongs), giving them ownership and a better understanding of the harder parts of the system. Third, and perhaps most important, the architect is writing the same business-related source code as the development team and is therefore better able to identify with the development team in terms of the pain they might be going through with processes, procedures, and the development environment.

Suppose, however, that the architect is not able to develop code with the development team. How can a software architect still remain hands-on and maintain some level of technical depth? There are four basic ways an architect can still remain hands-on at work without having to “practice coding from home” (although we recommend practicing coding at home as well).

Our advice when doing proof-of-concept work is that, whenever possible, the architect should write the best production-quality code they can. We recommend this practice for two reasons. First, quite often, throwaway proof-of-concept code goes into the source code repository and becomes the reference architecture or guiding example for others to follow. The last thing an architect would want is for their throwaway, sloppy code to be a representation of their typical work. The second reason is that by writing production-quality proof-of-concept code, the architect gets practice writing quality, well-structured code rather than continually developing bad coding practices.

A final technique to remain hands-on as an architect is to do frequent code reviews.

Chapter 3. Modularity

First, we want to untangle some common terms used and overused in discussions about architecture surrounding modularity and provide definitions for use throughout the book.

95% of the words [about software architecture] are spent extolling the benefits of “modularity” and that little, if anything, is said about how to achieve it.

Glenford J. Myers (1978)

Different platforms offer different reuse mechanisms for code, but all support some way of grouping related code together into modules. While this concept is universal in software architecture, it has proven slippery to define. A casual internet search yields dozens of definitions, with no consistency (and some contradictions). As you can see from the quote from Myers, this isn’t a new problem. However, because no recognized definition exists, we must jump into the fray and provide our own definitions for the sake of consistency throughout the book.

Understanding modularity and its many incarnations in the development platform of choice is critical for architects. Many of the tools we have to analyze architecture (such as metrics, fitness functions, and visualizations) rely on these modularity concepts. Modularity is an organizing principle. If an architect designs a system without paying attention to how the pieces wire together, they end up creating a system that presents myriad difficulties. To use a physics analogy, software systems model complex systems, which tend toward entropy (or disorder). Energy must be added to a physical system to preserve order. The same is true for software systems: architects must constantly expend energy to ensure good structural soundness, which won’t happen by accident.

Definition

package in Java, namespace in .NET, and so on). Developers typically use modules as a way to group related code together. For example, the com.mycompany.customer package in Java should contain things related to customers.Architects must be aware of how developers package things because it has important implications in architecture. For example, if several packages are tightly coupled together, reusing one of them for related work becomes more difficult.

For discussions about architecture, we use modularity as a general term to denote a related grouping of code: classes, functions, or any other grouping. This doesn’t imply a physical separation, merely a logical one; the difference is sometimes important. For example, lumping a large number of classes together in a monolithic application may make sense from a convenience standpoint. However, when it comes time to restructure the architecture, the coupling encouraged by loose partitioning becomes an impediment to breaking the monolith apart. Thus, it is useful to talk about modularity as a concept separate from the physical separation forced or implied by a particular platform.

Measuring Modularity

Cohesion

Cohesion refers to what extent the parts of a module should be contained within the same module. In other words, it is a measure of how related the parts are to one another. Ideally, a cohesive module is one where all the parts should be packaged together, because breaking them into smaller pieces would require coupling the parts together via calls between modules to achieve useful results.

Attempting to divide a cohesive module would only result in increased coupling and decreased readability.

Larry Constantine

Computer scientists have defined a range of cohesion measures, listed here from best to worst:

- Functional cohesion

-

Every part of the module is related to the other, and the module contains everything essential to function.

- Sequential cohesion

-

Two modules interact, where one outputs data that becomes the input for the other.

- Communicational cohesion

-

Two modules form a communication chain, where each operates on information and/or contributes to some output. For example, add a record to the database and generate an email based on that information.

- Procedural cohesion

-

Two modules must execute code in a particular order.

- Temporal cohesion

- Modules are related based on timing dependencies.For example, many systems have a list of seemingly unrelated things that must be initialized at system startup; these different tasks are temporally cohesive.

- Logical cohesion

-

The data within modules is related logically but not functionally. For example, consider a module that converts information from text, serialized objects, or streams. Operations are related, but the functions are quite different. A common example of this type of cohesion exists in virtually every Java project in the form of the

StringUtilspackage: a group of static methods that operate onStringbut are otherwise unrelated. - Coincidental cohesion

-

Elements in a module are not related other than being in the same source file; this represents the most negative form of cohesion.

Despite having seven variants listed, cohesion is a less precise metric than coupling. Often, the degree of cohesiveness of a particular module is at the discretion of a particular architect. For example, consider this module definition:

Customer Maintenance-

-

add customer -

update customer -

get customer -

notify customer -

get customer orders -

cancel customer orders

-

Should the last two entries reside in this module or should the developer create two separate modules, such as:

Customer Maintenance-

-

add customer -

update customer -

get customer -

notify customer

-

Order Maintenance-

-

get customer orders -

cancel customer orders

-

Which is the correct structure? As always, it depends:

-

Are those the only two operations for

Order Maintenance? If so, it may make sense to collapse those operations back intoCustomer Maintenance. -

Is

Customer Maintenanceexpected to grow much larger, encouraging developers to look for opportunities to extract behavior? -

Does

Order Maintenancerequire so much knowledge ofCustomerinformation that separating the two modules would require a high degree of coupling to make it functional? This relates back to the Larry Constantine quote.

These questions represent the kind of trade-off analysis at the heart of the job of a software architect.

The Chidamber and Kemerer Lack of Cohesion in Methods (LCOM) metric measures the structural cohesion of a module, typically a component. The initial version appears in Equation 3-1.

Equation 3-1. LCOM, version 1

P increases by one for any method that doesn’t access a particular shared field and Q decreases by one for methods that do share a particular shared field. The authors sympathize with those who don’t understand this formulation. Worse, it has gradually gotten more elaborate over time. The second variation introduced in 1996 (thus the name LCOM96B) appears in Equation 3-2.

Equation 3-2. LCOM 96b

We wont bother untangling the variables and operators in Equation 3-2 because the following written explanation is clearer. Basically, the LCOM metric exposes incidental coupling within classes. Here’s a better definition of LCOM:

- LCOM

-

The sum of sets of methods not shared via sharing fields

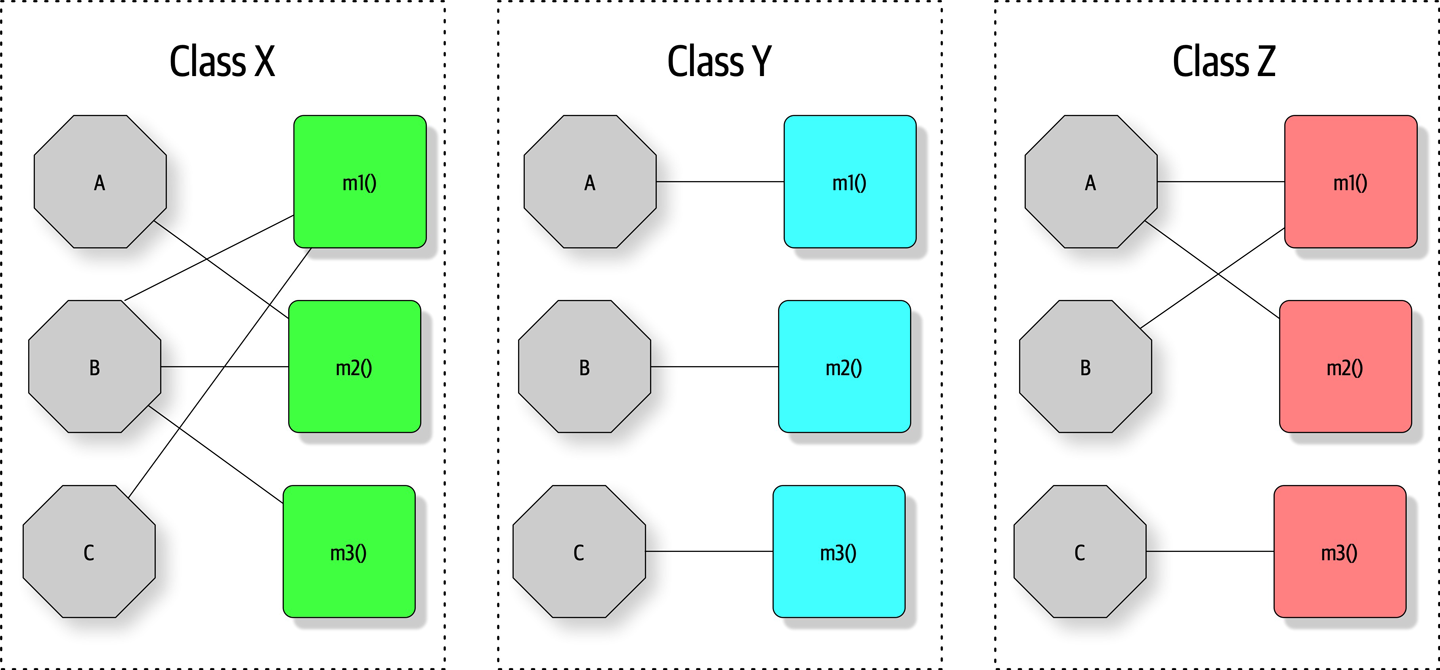

Consider a class with private fields a and b. Many of the methods only access a, and many other methods only access b. The sum of the sets of methods not shared via sharing fields (a and b) is high; therefore, this class reports a high LCOM score, indicating that it scores high in lack of cohesion in methods. Consider the three classes shown in Figure 3-1.

Figure 3-1. Illustration of the LCOM metric, where fields are octagons and methods are squares

In Figure 3-1, fields appear as single letters and methods appear as blocks. In Class X, the LCOM score is low, indicating good structural cohesion. Class Y, however, lacks cohesion; each of the field/method pairs in Class Y could appear in its own class without affecting behavior. Class Z shows mixed cohesion, where developers could refactor the last field/method combination into its own class.

The LCOM metric is useful to architects who are analyzing code bases in order to move from one architectural style to another. One of the common headaches when moving architectures are shared utility classes. Using the LCOM metric can help architects find classes that are incidentally coupled and should never have been a single class to begin with.

Many software metrics have serious deficiencies, and LCOM is not immune. All this metric can find is structural lack of cohesion; it has no way to determine logically if particular pieces fit together. This reflects back on our Second Law of Software Architecture: prefer why over how.

Coupling

Fortunately, we have better tools to analyze coupling in code bases, based in part on graph theory: because the method calls and returns form a call graph, analysis based on mathematics becomes possible. In 1979, Edward Yourdon and and Larry Constantine published Structured Design: Fundamentals of a Discipline of Computer Program and Systems Design (Prentice-Hall), defining many core concepts, including the metrics afferent and efferent coupling. Afferent coupling measures the number of incoming connections to a code artifact (component, class, function, and so on). Efferent coupling measures the outgoing connections to other code artifacts. For virtually every platform tools exist that allow architects to analyze the coupling characteristics of code in order to assist in restructuring, migrating, or understanding a code base.

Abstractness, Instability, and Distance from the Main Sequence

While the raw value of component coupling has value to architects, several other derived metrics allow a deeper evaluation. These metrics were created by Robert Martin for a C++ book, but are widely applicable to other object-oriented languages.

Abstractness is the ratio of abstract artifacts (abstract classes, interfaces, and so on) to concrete artifacts (implementation). It represents a measure of abstractness versus implementation. For example, consider a code base with no abstractions, just a huge, single function of code (as in a single main() method). The flip side is a code base with too many abstractions, making it difficult for developers to understand how things wire together (for example, it takes developers a while to figure out what to do with an AbstractSingletonProxyFactoryBean).

The formula for abstractness appears in Equation 3-3.

Equation 3-3. Abstractness

In the equation, represents abstract elements (interfaces or abstract classes) with the module, and represents concrete elements (nonabstract classes). This metric looks for the same criteria. The easiest way to visualize this metric: consider an application with 5,000 lines of code, all in one main() method. The abstractness numerator is 1, while the denominator is 5,000, yielding an abstractness of almost 0. Thus, this metric measures the ratio of abstractions in your code.

Architects calculate abstractness by calculating the ratio of the sum of abstract artifacts to the sum of the concrete ones.

Another derived metric, instability, is defined as the ratio of efferent coupling to the sum of both efferent and afferent coupling, shown in Equation 3-4.

Equation 3-4. Instability

In the equation, represents efferent (or outgoing) coupling, and represents afferent (or incoming) coupling.

The instability metric determines the volatility of a code base. A code base that exhibits high degrees of instability breaks more easily when changed because of high coupling. For example, if a class calls to many other classes to delegate work, the calling class shows high susceptibility to breakage if one or more of the called methods change.

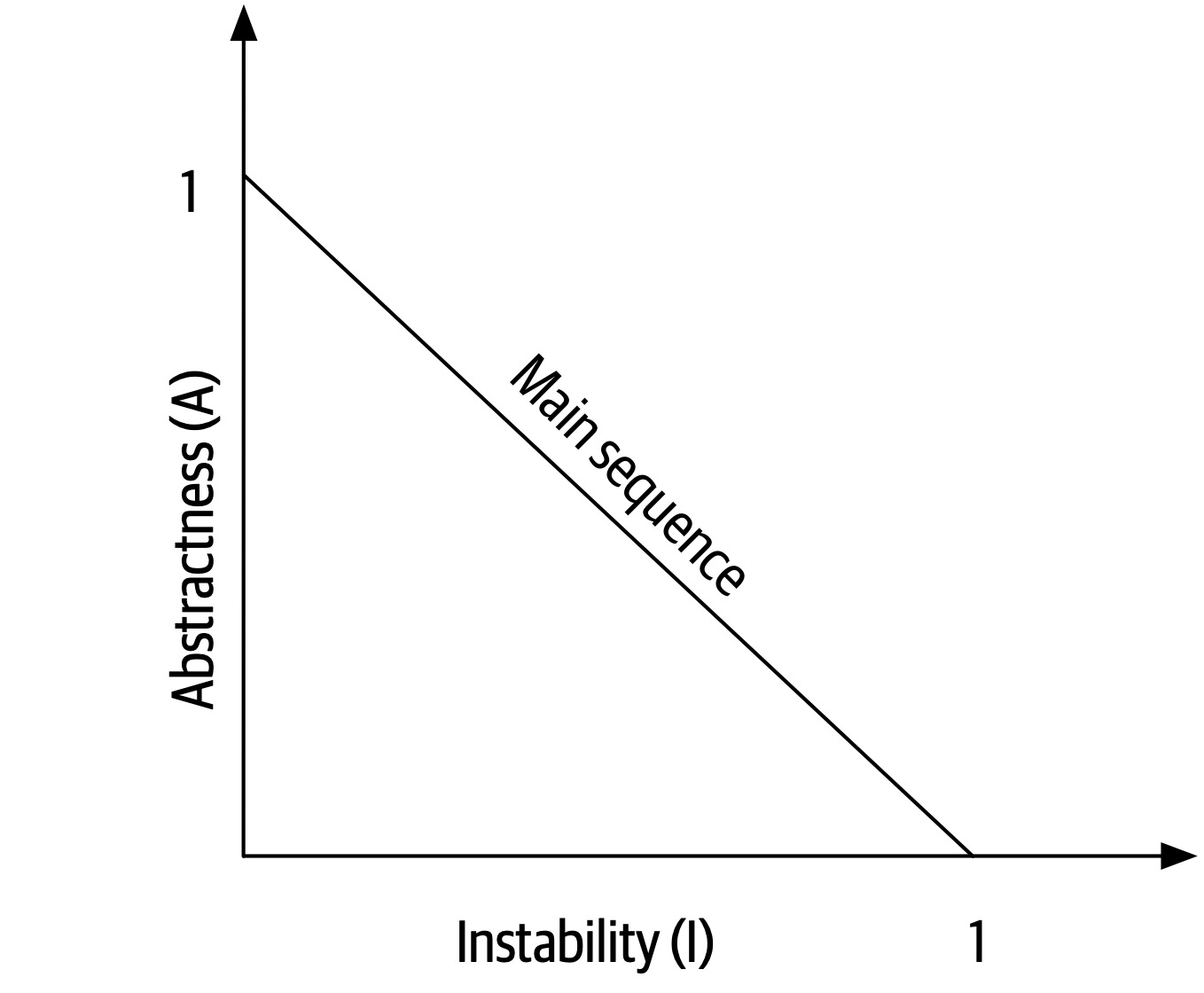

Distance from the Main Sequence

One of the few holistic metrics architects have for architectural structure is distance from the main sequence, a derived metric based on instability and abstractness, shown in Equation 3-5.

Equation 3-5. Distance from the main sequence

In the equation, A = abstractness and I = instability.

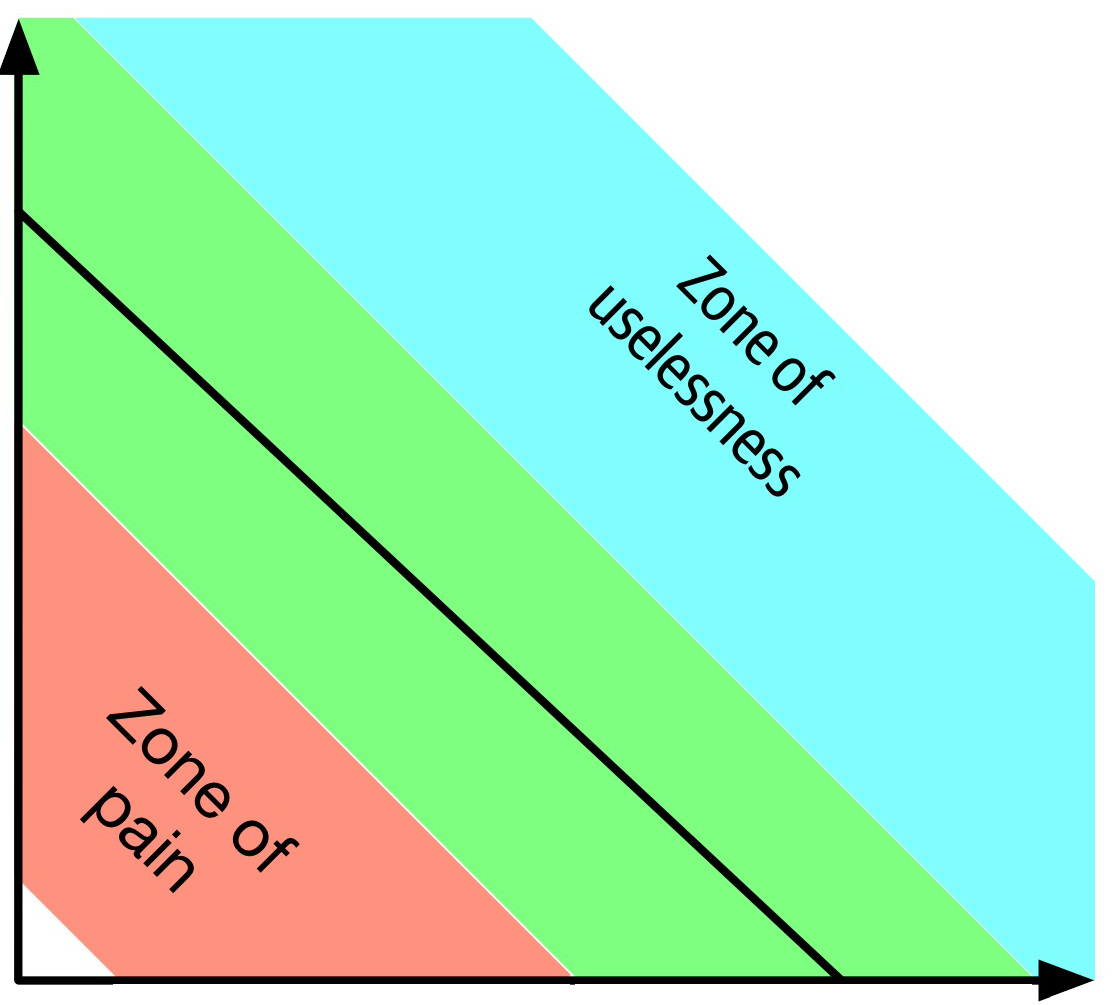

Note that both abstractness and instability are ratios, meaning their result will always fall between 0 and 1. Thus, when graphing the relationship, we see the graph in Figure 3-2.

Figure 3-2. The main sequence defines the ideal relationship between abstractness and instability

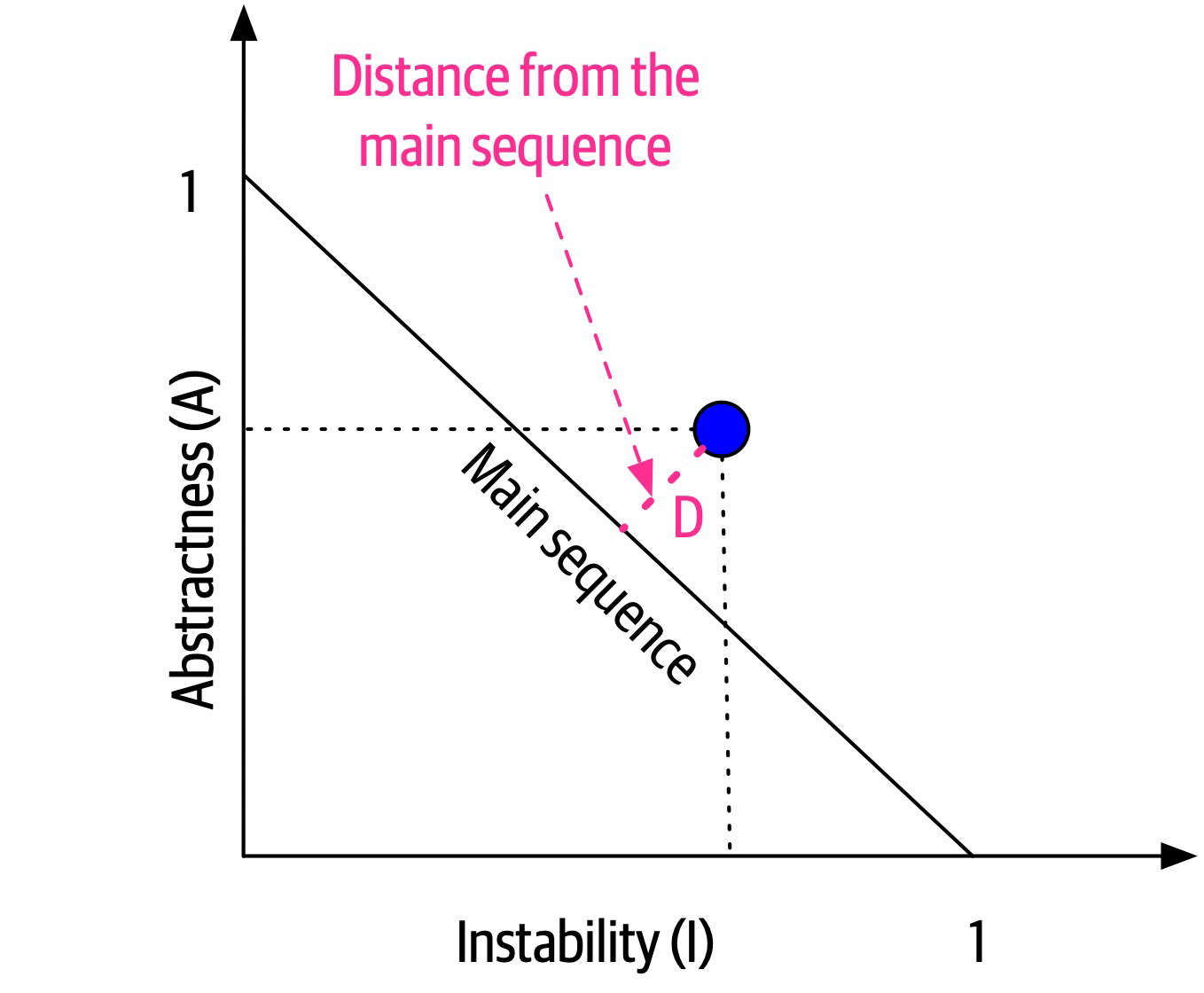

The distance metric imagines an ideal relationship between abstractness and instability; classes that fall near this idealized line exhibit a healthy mixture of these two competing concerns. For example, graphing a particular class allows developers to calculate the distance from the main sequence metric, illustrated in Figure 3-3.

Figure 3-3. Normalized distance from the main sequence for a particular class

In Figure 3-3, developers graph the candidate class, then measure the distance from the idealized line. The closer to the line, the better balanced the class. Classes that fall too far into the upper-righthand corner enter into what architects call the zone of uselessness: code that is too abstract becomes difficult to use. Conversely, code that falls into the lower-lefthand corner enter the zone of pain: code with too much implementation and not enough abstraction becomes brittle and hard to maintain, illustrated in Figure 3-4.

Figure 3-4. Zones of Uselessness and Pain

Tools exist in many platforms to provide these measures, which assist architects when analyzing code bases because of unfamiliarity, migration, or technical debt assessment.

Notice that the previously mentioned book by Edward Yourdon and and Larry Constantine (Structured Design: Fundamentals of a Discipline of Computer Program and Systems Design) predates the popularity of object-oriented languages, focusing instead on structured programming constructs, such as functions (not methods). It also defined other types of coupling that we do not cover here because they have been supplanted by connascence.

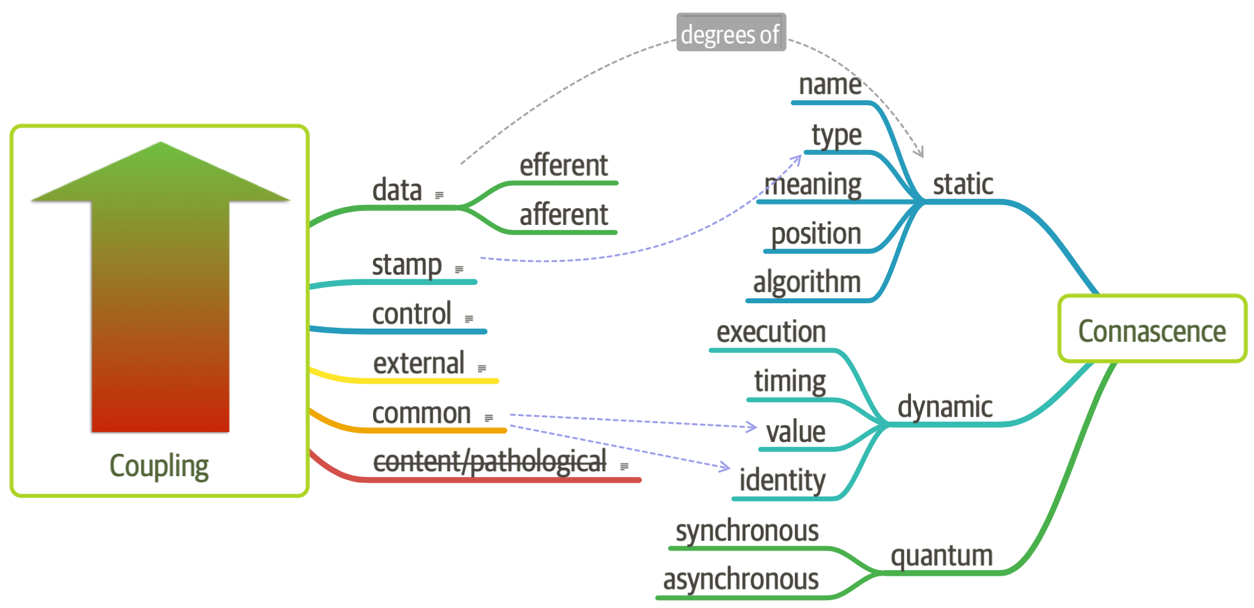

Connascence

In 1996, Meilir Page-Jones published What Every Programmer Should Know About Object-Oriented Design (Dorset House), refining the afferent and efferent coupling metrics and recasting them to object-oriented languages with a concept he named connascence. Here’s how he defined the term:

Two components are connascent if a change in one would require the other to be modified in order to maintain the overall correctness of the system.

Meilir Page-Jones

He developed two types of connascence: static and dynamic.

Static connascence

Static connascence refers to source-code-level coupling (as opposed to execution-time coupling, covered in “Dynamic connascence”); it is a refinement of the afferent and efferent couplings defined by Structured Design. In other words, architects view the following types of static connascence as the degree to which something is coupled, either afferently or efferently:

- Connascence of Name (CoN)

-

Multiple components must agree on the name of an entity.

Names of methods represents the most common way that code bases are coupled and the most desirable, especially in light of modern refactoring tools that make system-wide name changes trivial.

- Connascence of Type (CoT)

-

Multiple components must agree on the type of an entity.

This type of connascence refers to the common facility in many statically typed languages to limit variables and parameters to specific types. However, this capability isn’t purely a language feature—some dynamically typed languages offer selective typing, notably Clojure and Clojure Spec.

- Connascence of Meaning (CoM) or Connascence of Convention (CoC)

-

Multiple components must agree on the meaning of particular values.

The most common obvious case for this type of connascence in code bases is hard-coded numbers rather than constants. For example, it is common in some languages to consider defining somewhere

int TRUE = 1; int FALSE = 0. Imagine the problems if someone flips those values. - Connascence of Position (CoP)

-

Multiple entities must agree on the order of values.

This is an issue with parameter values for method and function calls even in languages that feature static typing. For example, if a developer creates a method

void updateSeat(String name, String seatLocation)and calls it with the valuesupdateSeat("14D", "Ford, N"), the semantics aren’t correct even if the types are. - Connascence of Algorithm (CoA)

-

Multiple components must agree on a particular algorithm.

A common case for this type of connascence occurs when a developer defines a security hashing algorithm that must run on both the server and client and produce identical results to authenticate the user. Obviously, this represents a high form of coupling—if either algorithm changes any details, the handshake will no longer work.

Dynamic connascence

The other type of connascence Page-Jones defined was dynamic connascence, which analyses calls at runtime. The following is a description of the different types of dynamic connascence:

- Connascence of Execution (CoE)

-

The order of execution of multiple components is important.

Consider this code:

email=newEmail();email.setRecipient("foo@example.com");email.setSender("me@me.com");email.send();email.setSubject("whoops");It won’t work correctly because certain properties must be set in order.

- Connascence of Timing (CoT)

-

The timing of the execution of multiple components is important.

The common case for this type of connascence is a race condition caused by two threads executing at the same time, affecting the outcome of the joint operation.

- Connascence of Values (CoV)

-

Occurs when several values relate on one another and must change together.

Consider the case where a developer has defined a rectangle as four points, representing the corners. To maintain the integrity of the data structure, the developer cannot randomly change one of points without considering the impact on the other points.

The more common and problematic case involves transactions, especially in distributed systems. When an architect designs a system with separate databases, yet needs to update a single value across all of the databases, all the values must change together or not at all.

- Connascence of Identity (CoI)

-

Occurs when several values relate on one another and must change together.

The common example of this type of connascence involves two independent components that must share and update a common data structure, such as a distributed queue.

Architects have a harder time determining dynamic connascence because we lack tools to analyze runtime calls as effectively as we can analyze the call graph.

Connascence properties

Connascence is an analysis tool for architect and developers, and some properties of connascence help developers use it wisely. The following is a description of each of these connascence properties:

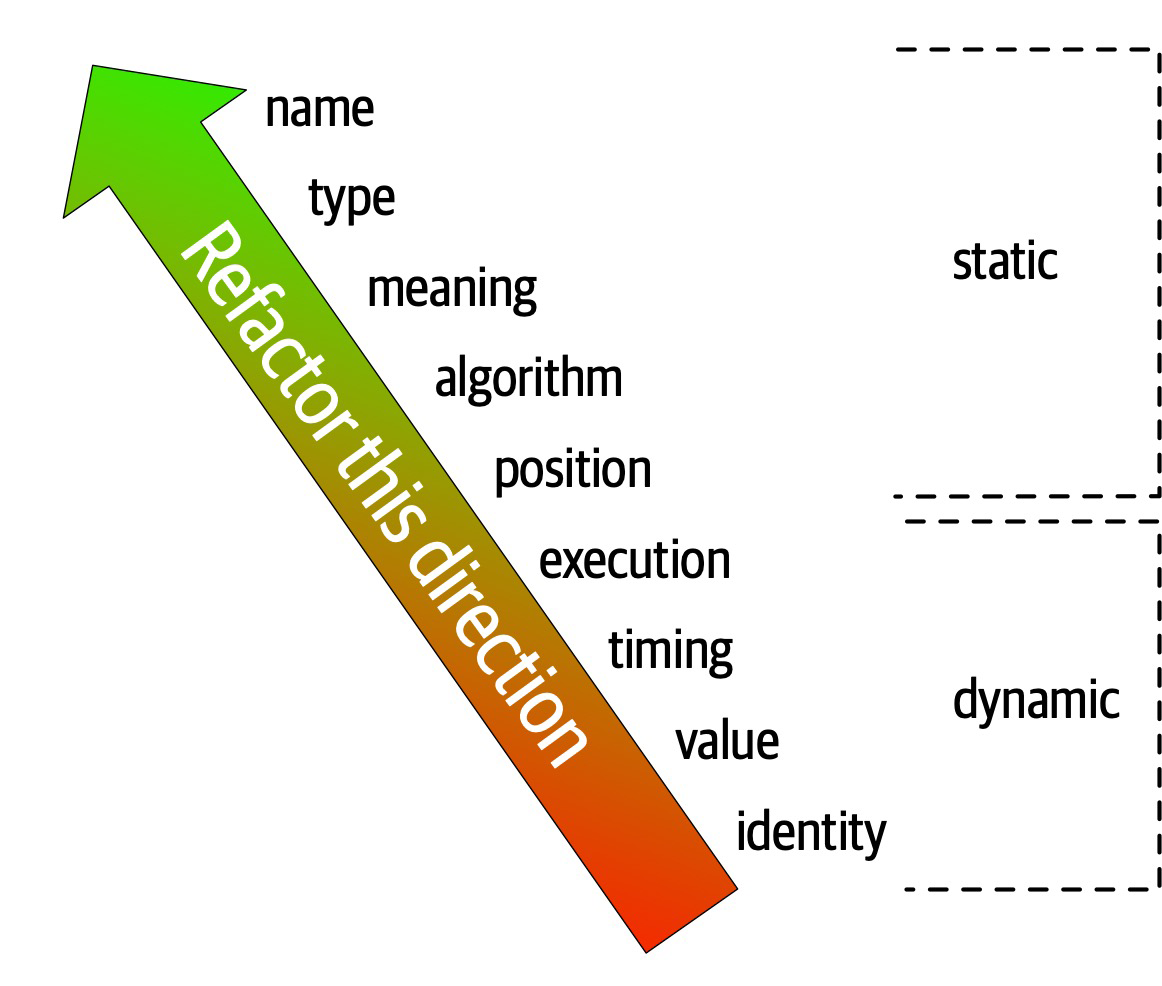

- Strength

-

Architects determine the strength of connascence by the ease with which a developer can refactor that type of coupling; different types of connascence are demonstrably more desirable, as shown in Figure 3-5. Architects and developers can improve the coupling characteristics of their code base by refactoring toward better types of connascence.

Architects should prefer static connascence to dynamic because developers can determine it by simple source code analysis, and modern tools make it trivial to improve static connascence. For example, consider the case of connascence of meaning, which developers can improve by refactoring to connascence of name by creating a named constant rather than a magic value.

Figure 3-5. The strength on connascence provides a good refactoring guide

- Locality

-

The locality of connascence measures how proximal the modules are to each other in the code base. Proximal code (in the same module) typically has more and higher forms of connascence than more separated code (in separate modules or code bases). In other words, forms of connascence that indicate poor coupling when far apart are fine when closer together. For example, if two classes in the same component have connascence of meaning, it is less damaging to the code base than if two components have the same form of connascence.

Developers must consider strength and locality together. Stronger forms of connascence found within the same module represent less code smell than the same connascence spread apart.

- Degree

-

The degree of connascence relates to the size of its impact—does it impact a few classes or many? Lesser degrees of connascence damage code bases less. In other words, having high dynamic connascence isn’t terrible if you only have a few modules. However, code bases tend to grow, making a small problem correspondingly bigger.

Page-Jones offers three guidelines for using connascence to improve systems modularity:

-

Minimize overall connascence by breaking the system into encapsulated elements

-

Minimize any remaining connascence that crosses encapsulation boundaries

-

Maximize the connascence within encapsulation boundaries

The legendary software architecture innovator Jim Weirich repopularized the concept of connascence and offers two great pieces of advice:

Rule of Degree: convert strong forms of connascence into weaker forms of connascence

Rule of Locality: as the distance between software elements increases, use weaker forms of connascence

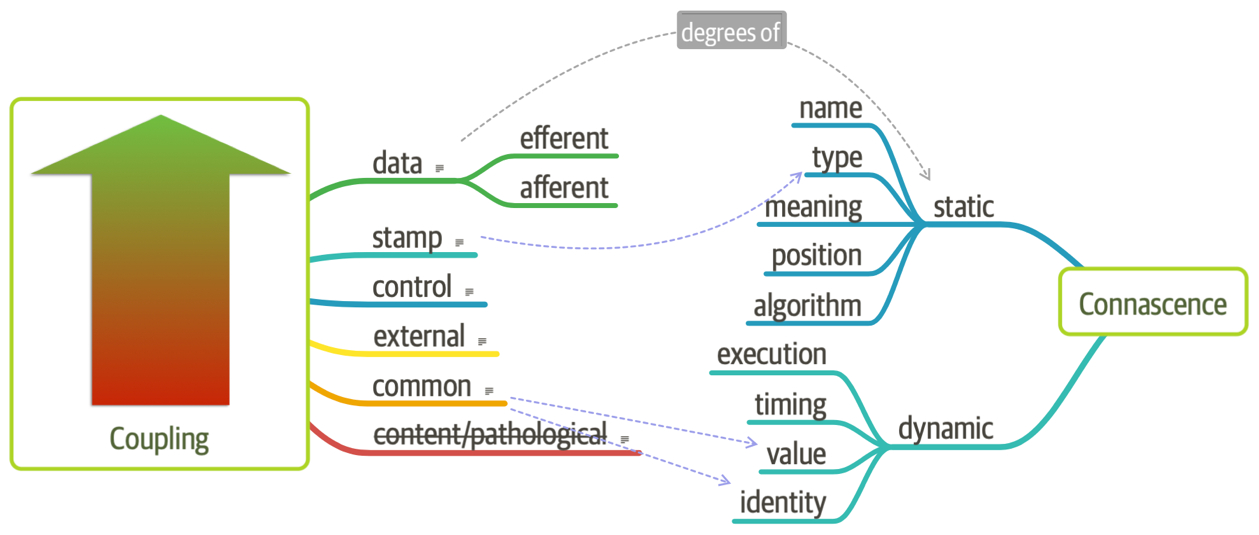

Unifying Coupling and Connascence Metrics

So far, we’ve discussed both coupling and connascence, measures from different eras and with different targets. However, from an architect’s point of view, these two views overlap. What Page-Jones identifies as static connascence represents degrees of either incoming or outgoing coupling. Structured programming only cares about in or out, whereas connascence cares about how things are coupled together. To help visualize the overlap in concepts, consider Figure 3-6.

Figure 3-6. Unifying coupling and connascence

In Figure 3-6, the structured programming coupling concepts appear on the left, while the connascence characteristics appear on the right. What structured programming called data coupling (method calls), connascence provides advice for how that coupling should manifest. Structured programming didn’t really address the areas covered by dynamic connascence; we encapsulate that concept shortly in “Architectural Quanta and Granularity”.

The problems with 1990s connascence

Several problems exist for architects when applying these useful metrics for analyzing and designing systems. First, these measures look at details at a low level of code, focusing on code quality and hygiene than necessarily architectural structure. Architects tend to care more about how modules are coupled rather than the degree of coupling. For example, an architect cares about synchronous versus asynchronous communication, and doesn’t care so much about how that’s implemented.

The second problem with connascence lies with the fact that it doesn’t really address a fundamental decision that many modern architects must make—synchronous or asynchronous communication in distributed architectures like microservices? Referring back to the First Law of Software Architecture, everything is a trade-off. After we discuss the scope of architecture characteristics in Chapter 7, we’ll introduce new ways to think about modern connascence.

From Modules to Components

We use the term module throughout as a generic name for a bundling of related code. However, most platforms support some form of component, one of the key building blocks for software architects. The concept and corresponding analysis of the logical or physical separation has existed since the earliest days of computer science. Yet, with all the writing and thinking about components and separation, developers and architects still struggle with achieving good outcomes.

Chapter 4. Architecture Characteristics Defined

A company decides to solve a particular problem using software, so it gathers a list of requirements for that system.

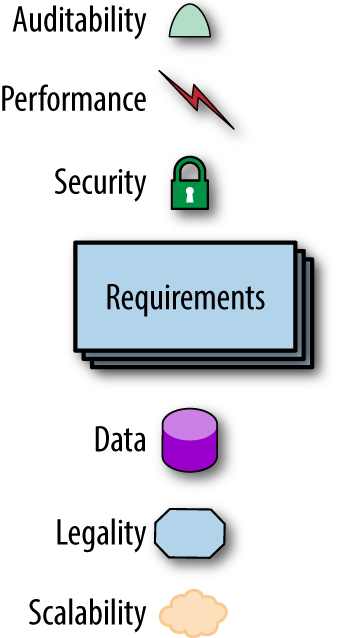

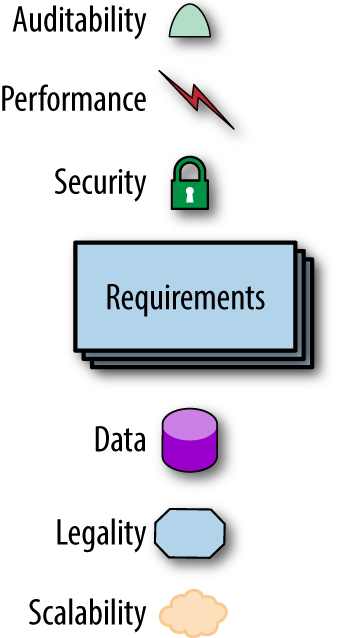

Figure 4-1. A software solution consists of both domain requirements and architectural characteristics

Architects may collaborate on defining the domain or business requirements, but one key responsibility entails defining, discovering, and otherwise analyzing all the things the software must do that isn’t directly related to the domain functionality: architectural characteristics.

What distinguishes software architecture from coding and design? Many things, including the role that architects have in defining architectural characteristics, the important aspects of the system independent of the problem domain. Many organizations describe these features of software with a variety of terms, including nonfunctional requirements, but we dislike that term because it is self-denigrating. Architects created that term to distinguish architecture characteristics from functional requirements, but naming something nonfunctional has a negative impact from a language standpoint: how can teams be convinced to pay enough attention to something “nonfunctional”? Another popular term is quality attributes, which we dislike because it implies after-the-fact quality assessment rather than design. We prefer architecture characteristics because it describes concerns critical to the success of the architecture, and therefore the system as a whole, without discounting its importance.

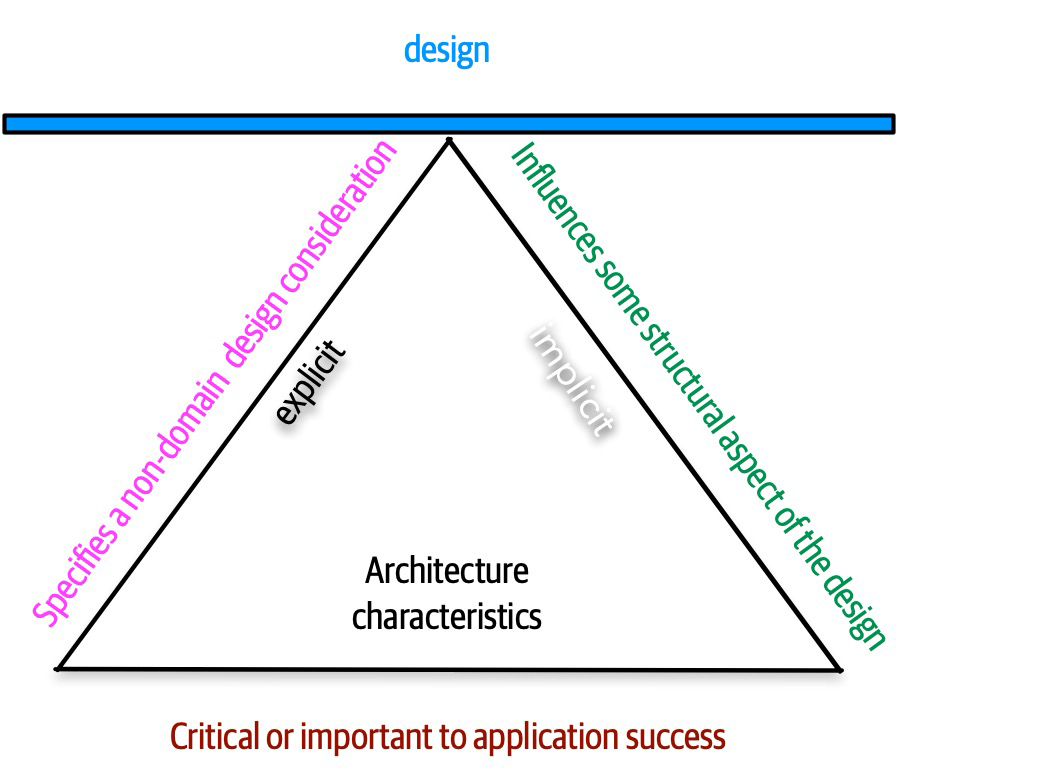

An architecture characteristic meets three criteria:

-

Specifies a nondomain design consideration

-

Influences some structural aspect of the design

-

Is critical or important to application success

These interlocking parts of our definition are illustrated in Figure 4-2.

Figure 4-2. The differentiating features of architecture characteristics

The definition illustrated in Figure 4-2 consists of the three components listed, in addition to a few modifiers:

- Specifies a nondomain design consideration

-

When designing an application, the requirements specify what the application should do; architecture characteristics specify operational and design criteria for success, concerning how to implement the requirements and why certain choices were made. For example, a common important architecture characteristic specifies a certain level of performance for the application, which often doesn’t appear in a requirements document. Even more pertinent: no requirements document states “prevent technical debt,” but it is a common design consideration for architects and developers. We cover this distinction between explicit and implicit characteristics in depth in “Extracting Architecture Characteristics from Domain Concerns”.

- Influences some structural aspect of the design