- Foreword

- Preface

- Introduction

- I. Strategic Design

- 1. Analyzing Business Domains

- 2. Discovering Domain Knowledge

- 3. Managing Domain Complexity

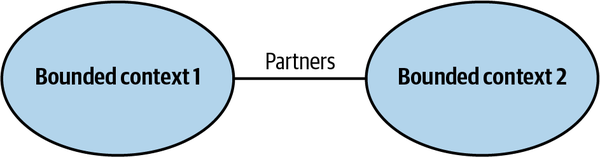

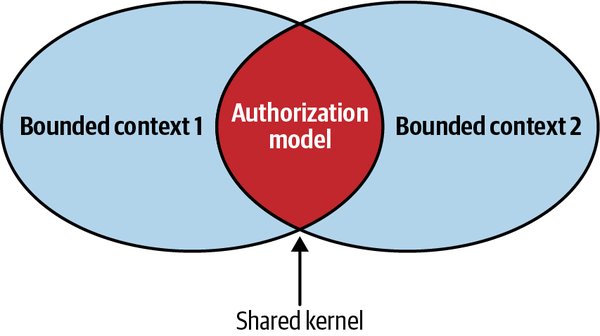

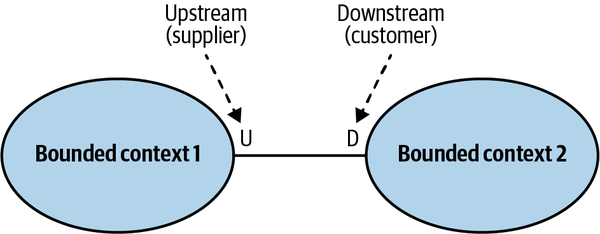

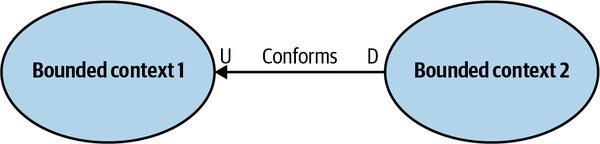

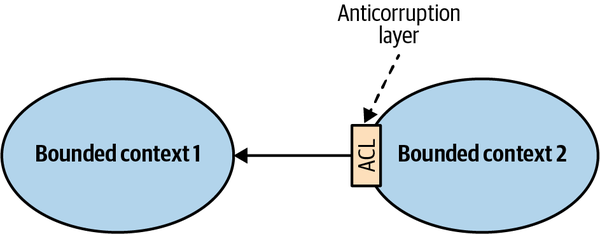

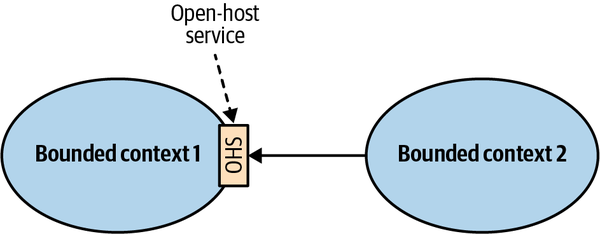

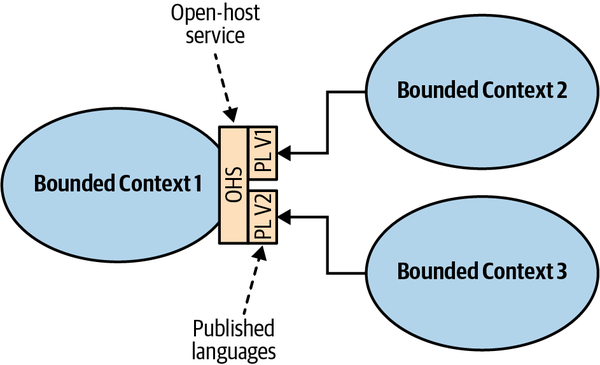

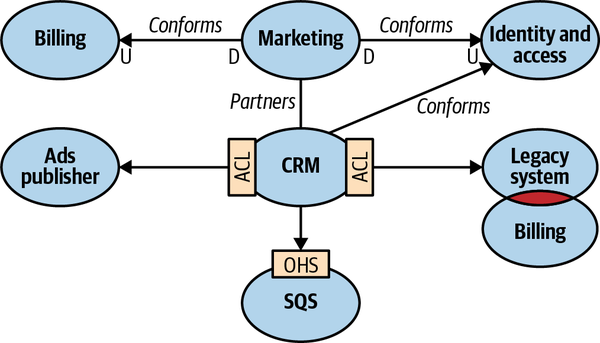

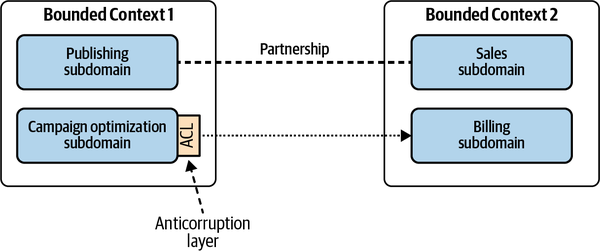

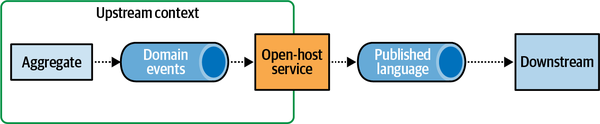

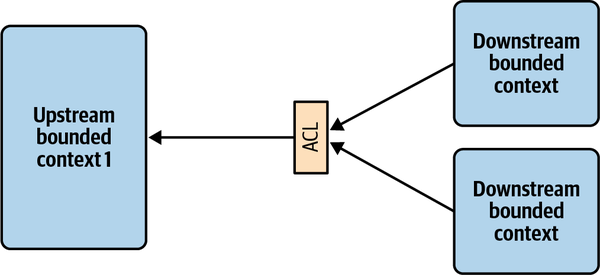

- 4. Integrating Bounded Contexts

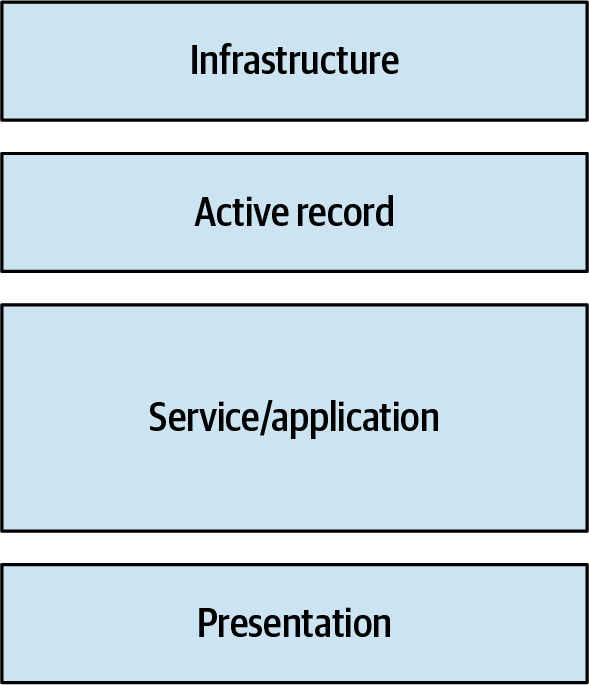

- II. Tactical Design

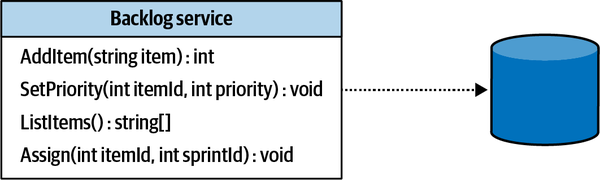

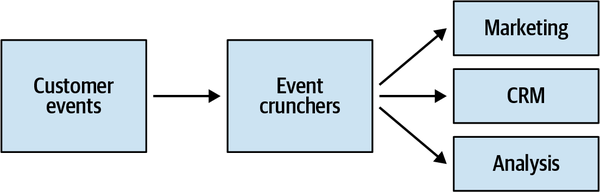

- 5. Implementing Simple Business Logic

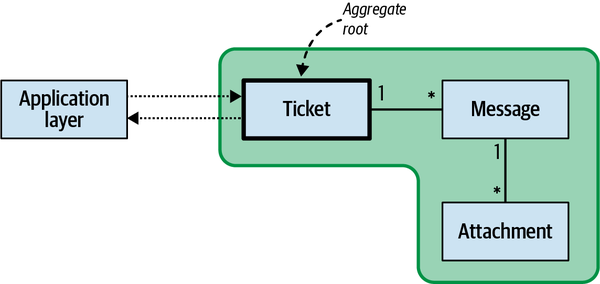

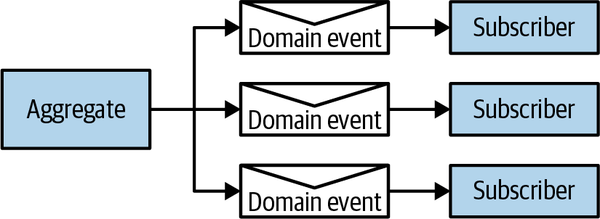

- 6. Tackling Complex Business Logic

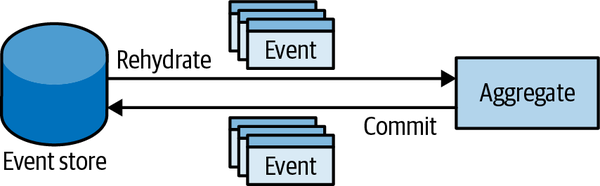

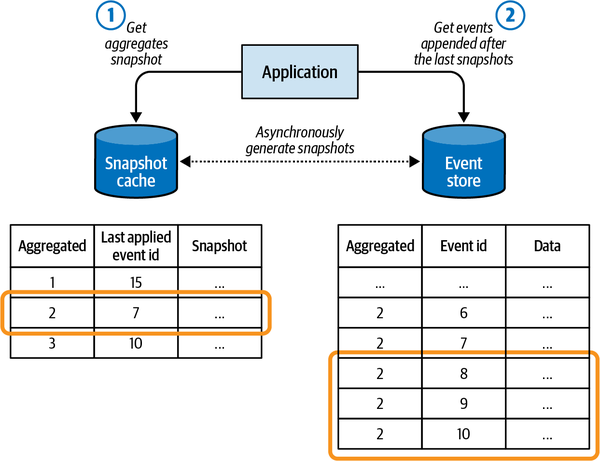

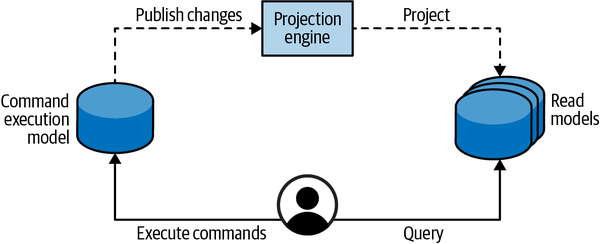

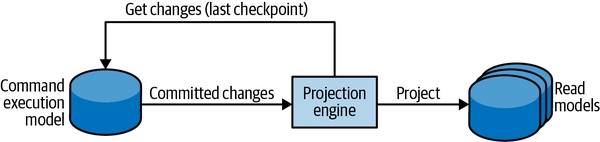

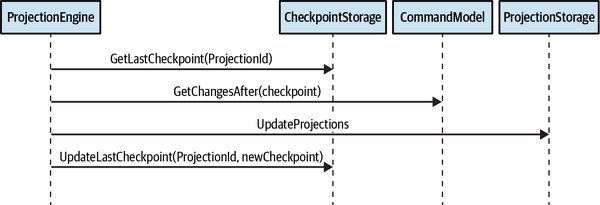

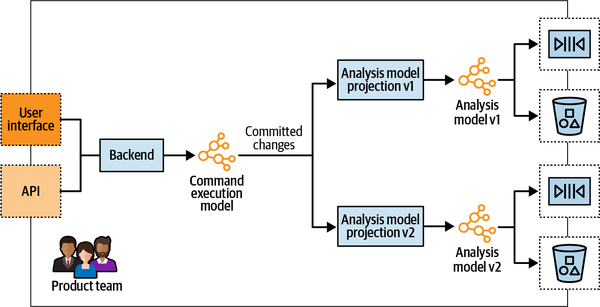

- 7. Modeling the Dimension of Time

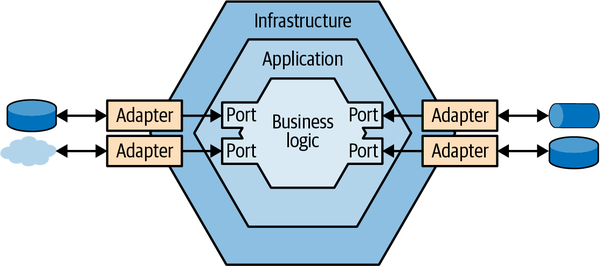

- 8. Architectural Patterns

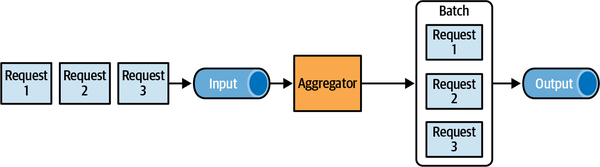

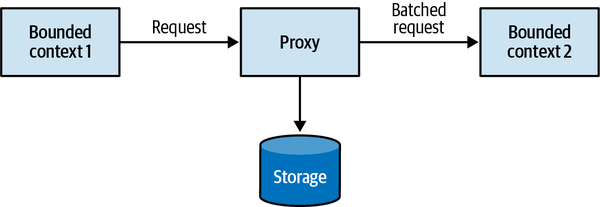

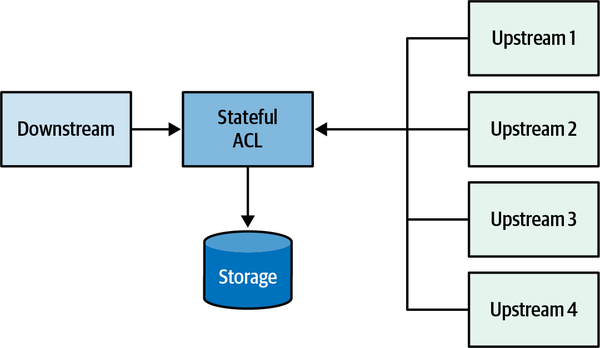

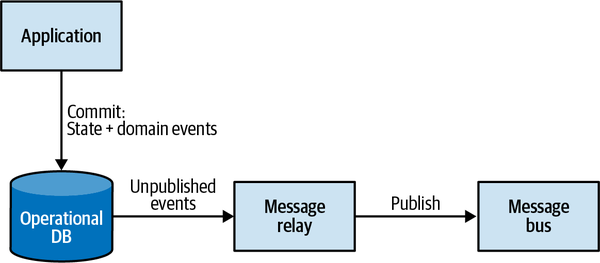

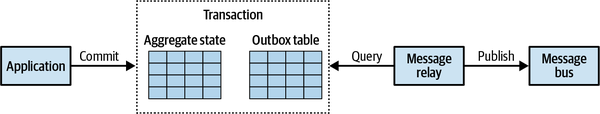

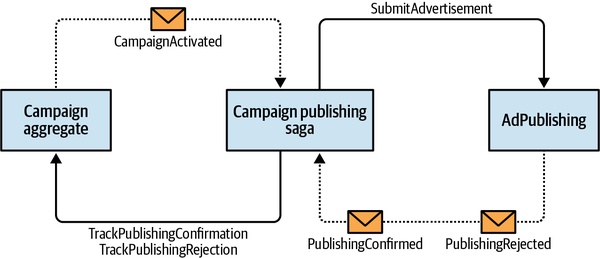

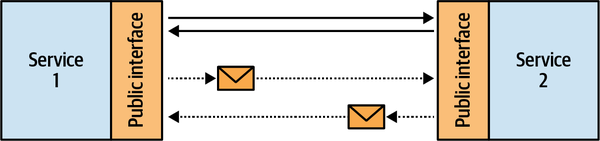

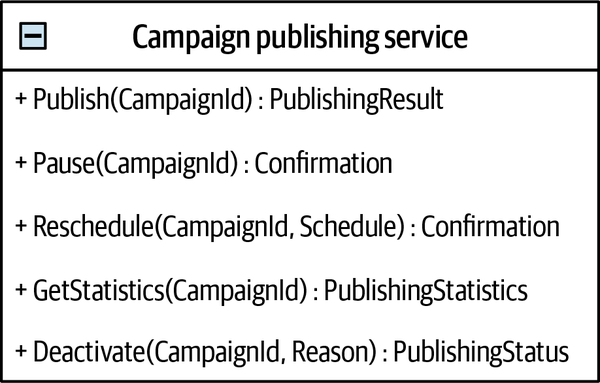

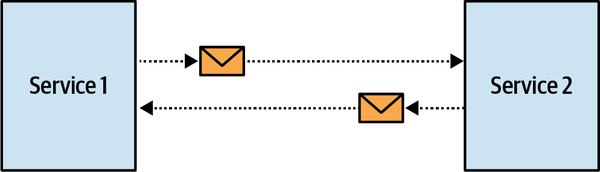

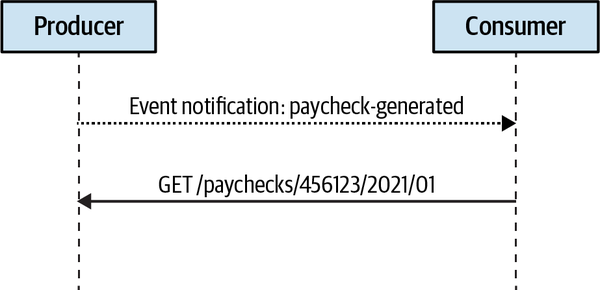

- 9. Communication Patterns

- III. Applying Domain-Driven Design in Practice

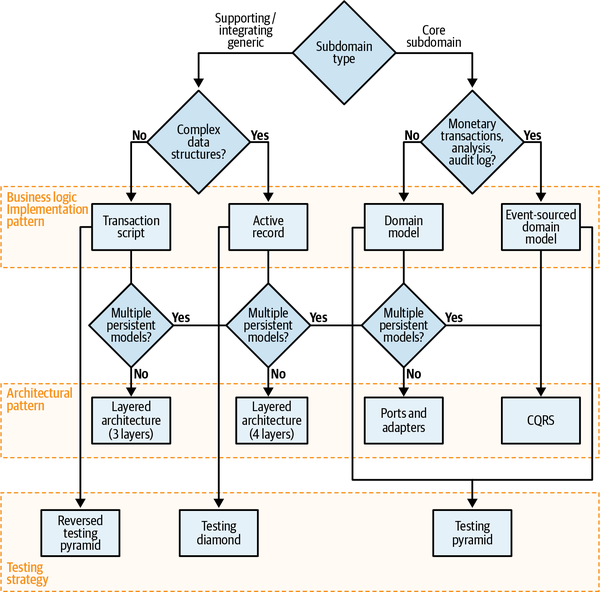

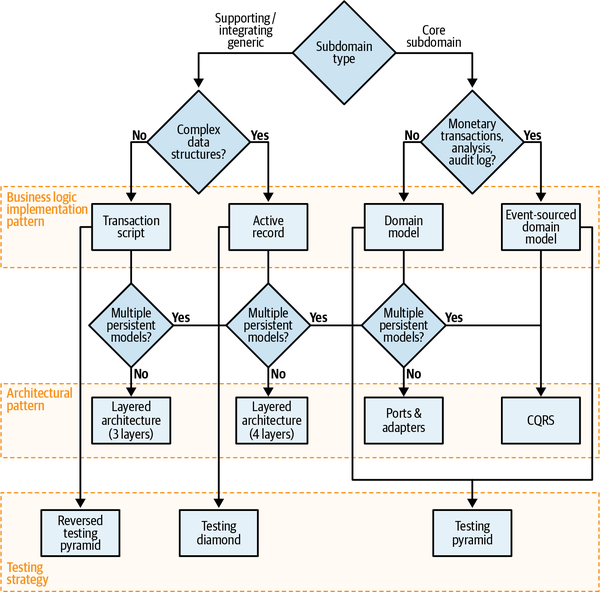

- 10. Design Heuristics

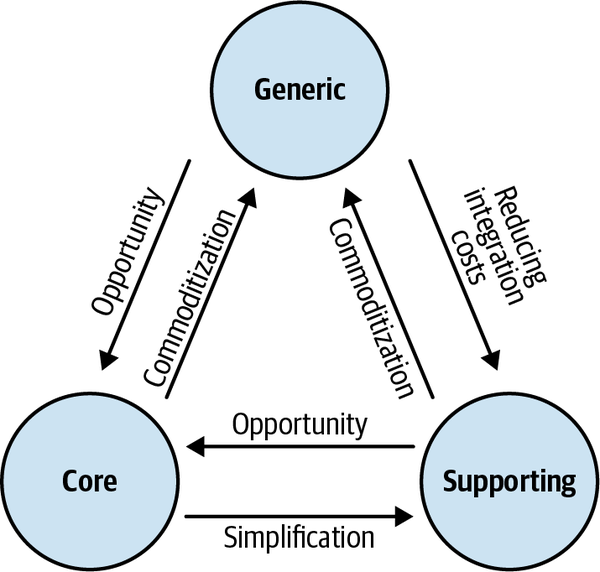

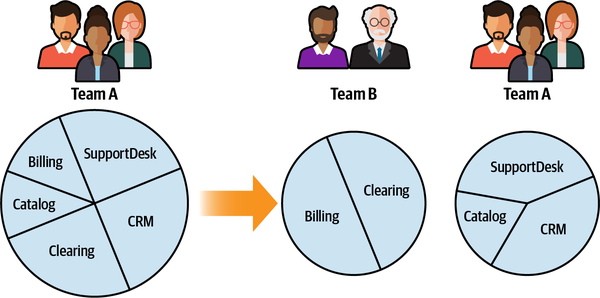

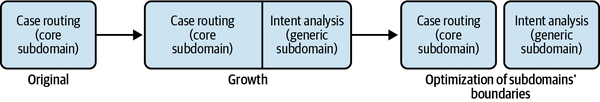

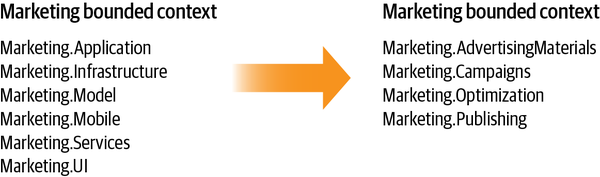

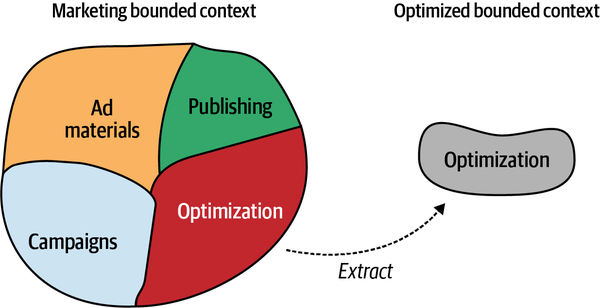

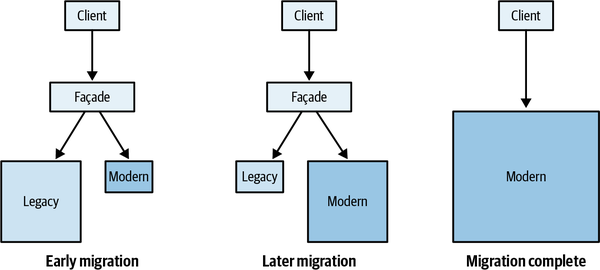

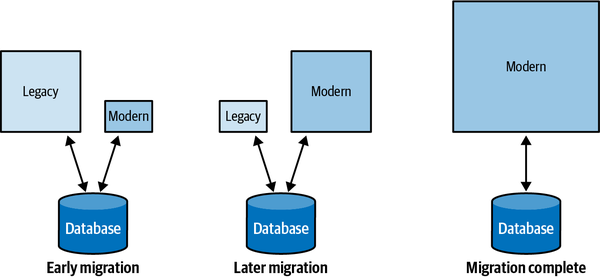

- 11. Evolving Design Decisions

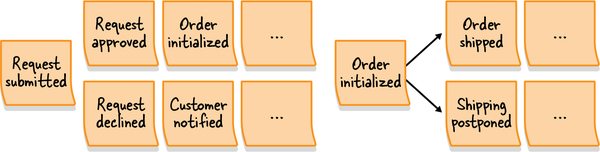

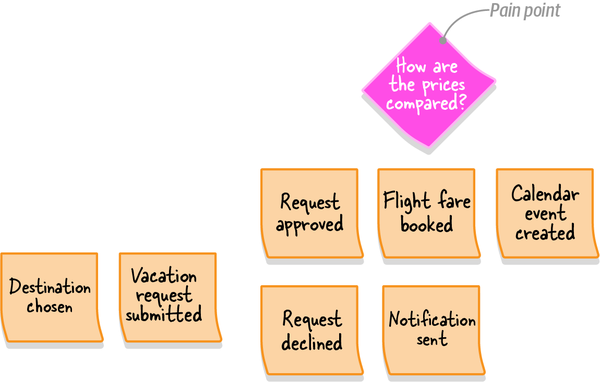

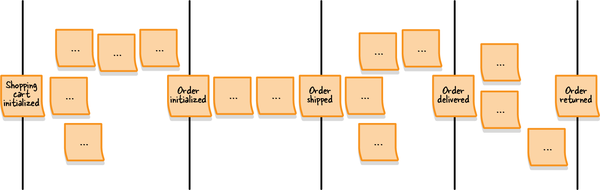

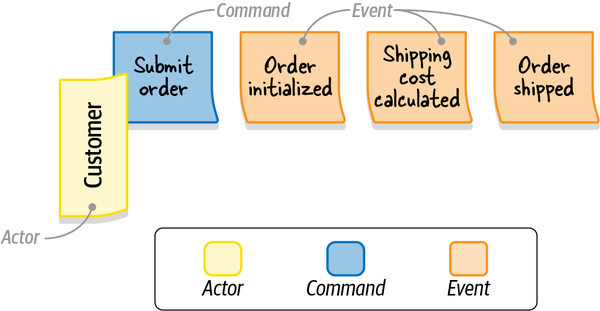

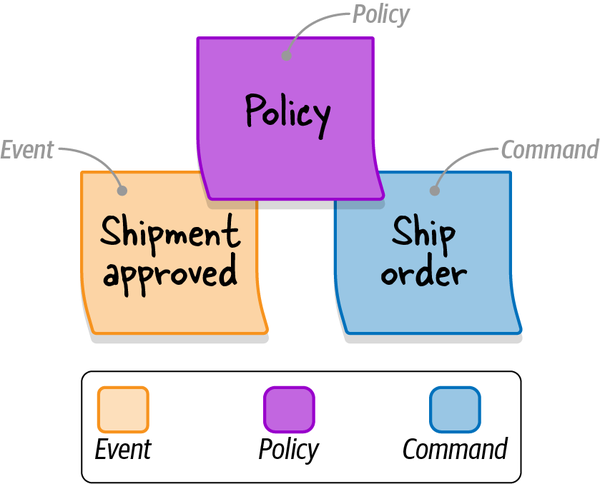

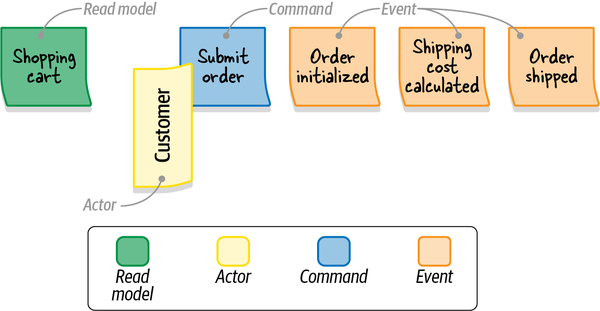

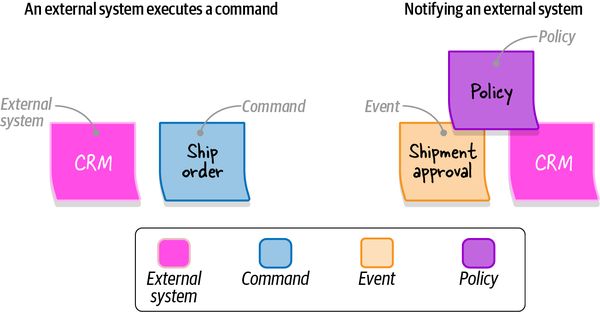

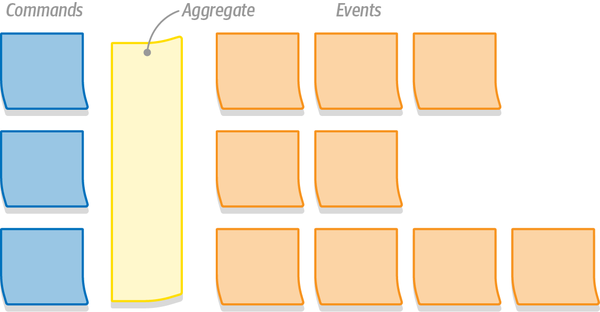

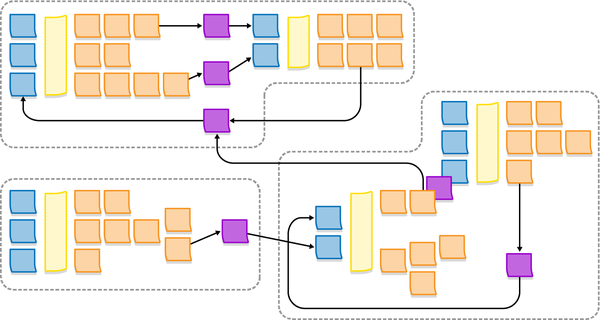

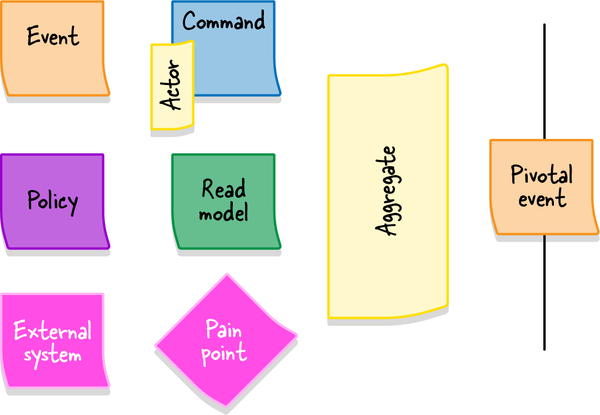

- 12. EventStorming

- 13. Domain-Driven Design in the Real World

- IV. Relationships to Other Methodologies and Patterns

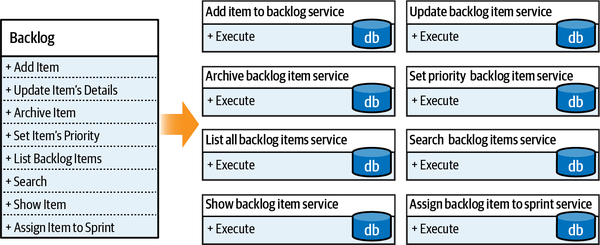

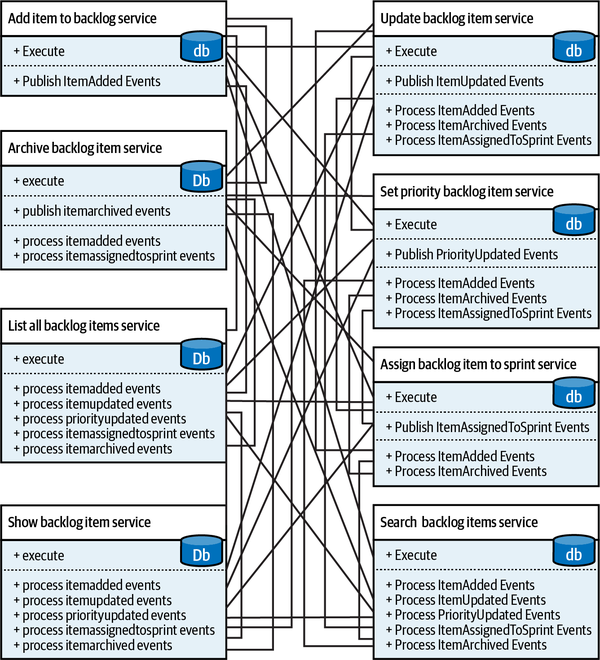

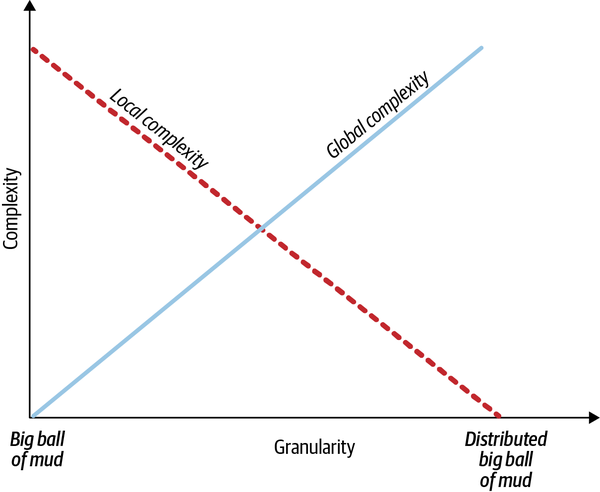

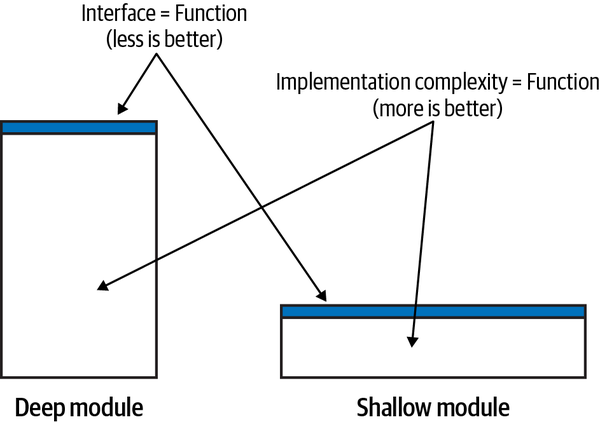

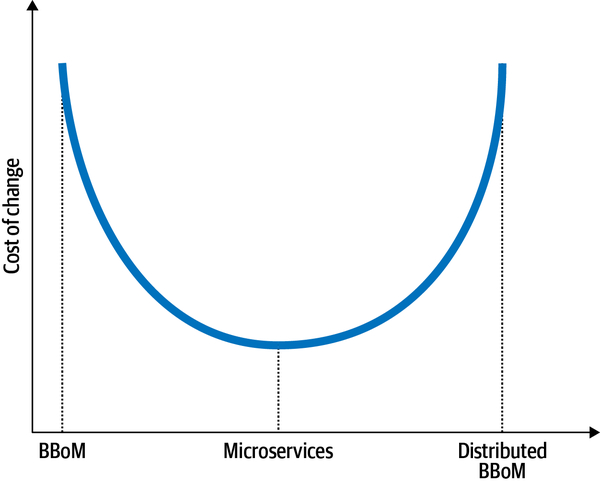

- 14. Microservices

- 15. Event-Driven Architecture

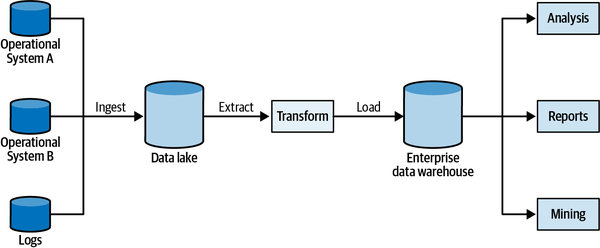

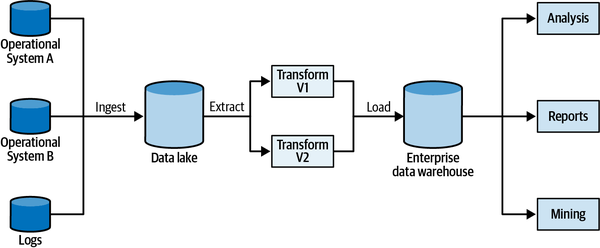

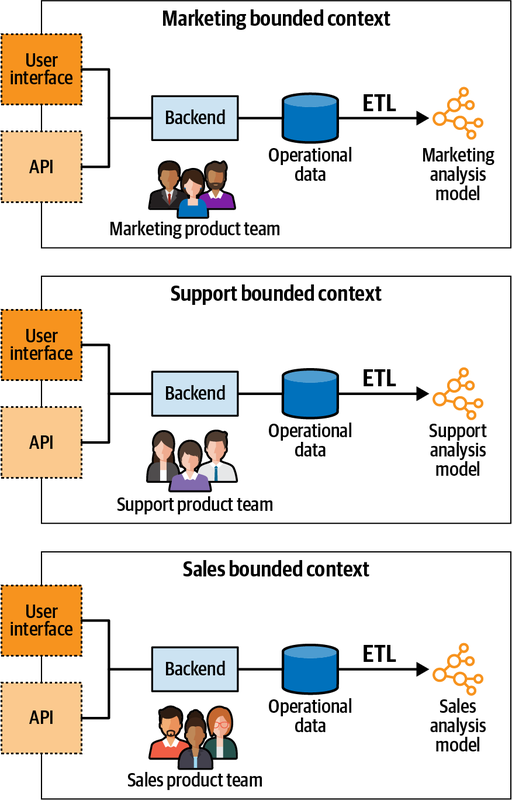

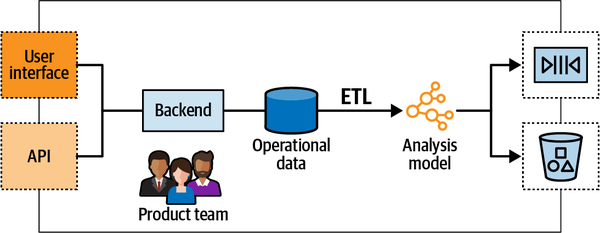

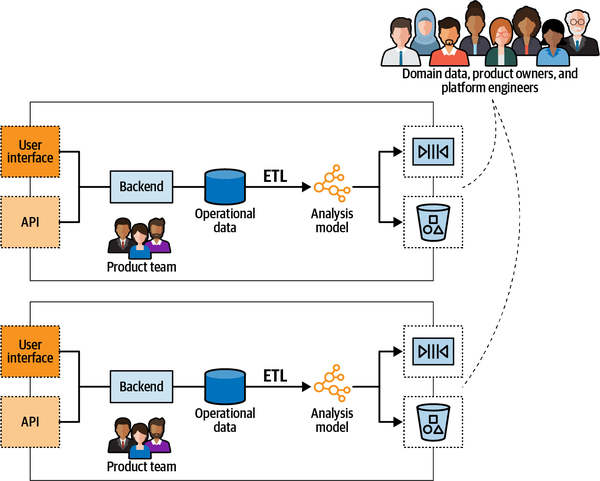

- 16. Data Mesh

- Closing Words

- A. Applying DDD: A Case Study

- B. Answers to Exercise Questions

- References

- Index

Praise for Learning Domain-Driven Design

“Vladik Khononov is a unique thinker who has been applying DDD to solve real business problems for years. His ideas constantly move the whole DDD community forward, and this book will inspire beginning DDD practitioners.”

Nick Tune, Technology Consultant

“Reflecting on my readings of drafts of this book, the thing that comes to mind, with a great deal of joy at the thought, is that it delivers on its title! It is an inviting and informative practice guide, covering the scope of DDD from strategy to technical design. I’ve gained new insight and understanding in areas where I have experience and filled in concepts and practices I’d had less exposure to. Vlad is a wonderful teacher!”

Ruth Malan, Architecture Consultant at Bredemeyer Consulting

“Vlad has a lot of hard-won experience as a DDD practitioner working on some deeply complex projects and has been generous in sharing that knowledge. In this book, he tells the story of DDD in a unique way providing a great perspective for learning. This book is aimed at newcomers, yet as a longtime DDD practitioner who also writes and speaks about DDD, I found that I learned so much from his perspective.”

Julie Lerman, Software Coach, O’Reilly Author, and Serial DDD Advocate

Learning Domain-Driven Design

Aligning Software Architecture and Business Strategy

Vlad Khononov

Learning Domain-Driven Design

by Vlad Khononov

Copyright © 2022 Vladislav Khononov. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472.

O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (http://oreilly.com). For more information, contact our corporate/institutional sales department: 800-998-9938 or corporate@oreilly.com.

- Acquisitions Editor: Melissa Duffield

- Development Editor: Jill Leonard

- Production Editor: Katherine Tozer

- Copyeditor: Audrey Doyle

- Proofreader: James Fraleigh

- Indexer: Sue Klefstad

- Interior Designer: David Futato

- Cover Designer: Karen Montgomery

- Illustrator: Kate Dullea

- October 2021: First Edition

Revision History for the First Edition

- 2021-10-08: First Release

See http://oreilly.com/catalog/errata.csp?isbn=9781098100131 for release details.

The O’Reilly logo is a registered trademark of O’Reilly Media, Inc. Learning Domain-Driven Design, the cover image, and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc.

The views expressed in this work are those of the author, and do not represent the publisher’s views. While the publisher and the author have used good faith efforts to ensure that the information and instructions contained in this work are accurate, the publisher and the author disclaim all responsibility for errors or omissions, including without limitation responsibility for damages resulting from the use of or reliance on this work. Use of the information and instructions contained in this work is at your own risk. If any code samples or other technology this work contains or describes is subject to open source licenses or the intellectual property rights of others, it is your responsibility to ensure that your use thereof complies with such licenses and/or rights.

978-1-098-10013-1

[LSI]

Foreword

Domain-driven design provides a set of practices for a

Over the years since the publication of “The Blue Book,” not only have many organizations benefited from the ideas, but a community of experienced DDD practitioners has evolved. And the collaborative nature of DDD has resulted in this community sharing their experiences and perspective and creating tools to help teams embrace and benefit from these ideas. In a keynote at Explore DDD in 2019, Eric Evans encouraged the community to continue to evolve DDD—not only its practices but in finding ways to more effectively share its ideas.

And this brings me to why I am such a fan of Learning Domain-Driven Design. I was already a fan of Vlad through his conference speaking and other writings. He has a lot of hard-won experience as a DDD practitioner working on some deeply complex projects and has been generous in sharing that knowledge. In this book, he tells the “story” of DDD (not its history, but its concepts) in a unique way, providing a great perspective for learning. This book is aimed at newcomers, yet as a longtime DDD practitioner who also writes and speaks about DDD, I found that I learned so much from his perspective. I was eager to reference his book in my DDD Fundamentals course on Pluralsight before the book was even published and have already been sharing some of this perspective in conversations with clients.

Getting started with DDD can be confusing. Just as we use DDD to reduce the complexity of projects, Vlad presents DDD in a way that reduces the complexity of the topic itself. And he does more than explain the principles of DDD. The latter portion of the book shares some important practices that have evolved from DDD, such as EventStorming, addresses the problem of evolving the business focus or organization and how this might affect the software, and discusses how DDD aligns with microservices and how you can integrate it with a slew of well-known software patterns. I think Learning Domain-Driven Design will be an excellent introduction to DDD for newcomers, and a very worthy read for experienced practitioners as well.

Julie Lerman

Software Coach, O’Reilly Author,

and Serial DDD Advocate

Preface

I vividly remember the day I started my first real software engineering job. I was both ecstatic and terrified. After hacking software for local businesses during my high school years, I was eager to become a “real programmer” and write some code for one of the country’s largest outsourcing companies.

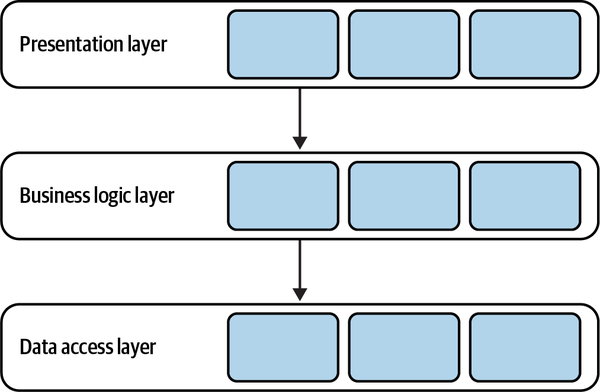

In my first days there, my new colleagues were showing me the ropes. After setting up the corporate email and going through the time-tracking system, we finally moved on to the interesting stuff: the company’s coding style and standards. I was told that “here, we always write well-designed code and use the

“But what about the business logic layer?”

“That one is straightforward. Here is where you implement the business logic.”

“But what is business logic?”

“Oh, business logic is all the loops and ‘if-else’ statements you need in order to implement the requirements.”

That day I began my journey to find out what exactly business logic is and how on earth it should be implemented in well-designed code. It took me more than three years to finally find the answer.

Eventually, though, everything fell into place, and I made peace with the domain-driven design (DDD) methodology. I learned the principles and patterns of DDD, the intricacies of modeling and implementing the business logic, and how to tackle the complexity in the heart of the software that I was building. Despite the obstacles, it definitely was worth it. Getting into domain-driven design was a career-changing experience for me.

Why I Wrote This Book

Over the past 10 years, I have introduced domain-driven design to my colleagues at different companies, conducted in-person classes, and taught online courses. The teaching perspective not only helped me deepen my knowledge, but also allowed me to optimize the way I explain the principles and patterns of domain-driven design.

This book is the result of my efforts. Its goal is to democratize domain-driven design; make it easier to understand and more accessible to employ. I believe that the DDD methodology is absolutely invaluable, especially when designing modern software systems. This book will give you just enough tools to start applying domain-driven design in your day-to-day work.

Who Should Read This Book

I believe that knowledge of domain-driven design principles and patterns will be useful for software engineers at all levels: junior, senior, staff, and principal.

Ultimately, in this book we will discuss not only how to design software, but also how to co-evolve the design with changes in its business context. That crucial aspect of software engineering will help you keep the system’s design “in shape” over time and prevent its degradation into a big ball of mud.

Navigating the Book

Here is a short summary of what you will find in each chapter:

-

Chapter 1 establishes the context of a software engineering project: the business domain, its goals, and how the software is intended to support them.

-

Chapter 2 introduces the notion of a “ubiquitous language”: domain-driven design’s practice for effective communication and knowledge sharing.

-

Chapter 3 discusses how to tackle the complexity of business domains and design the system’s high-level architectural components: bounded contexts.

-

Chapter 4 explores the different patterns of organizing the communication and integration between the bounded contexts.

-

Chapter 5 starts the discussion of business logic implementation patterns with two patterns addressing the cases of simple business logic.

-

Chapter 6 advances from simple to complex business logic and introduces the domain model pattern for tackling its complexity.

-

Chapter 7 adds the perspective of time and introduces an even more advanced way to model and implement business logic: the event-sourced domain model.

-

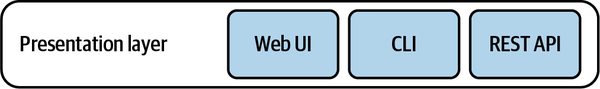

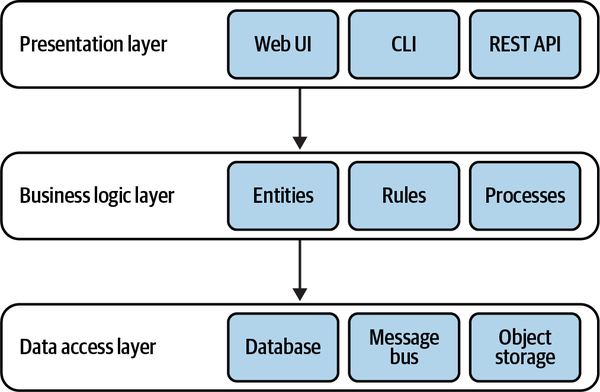

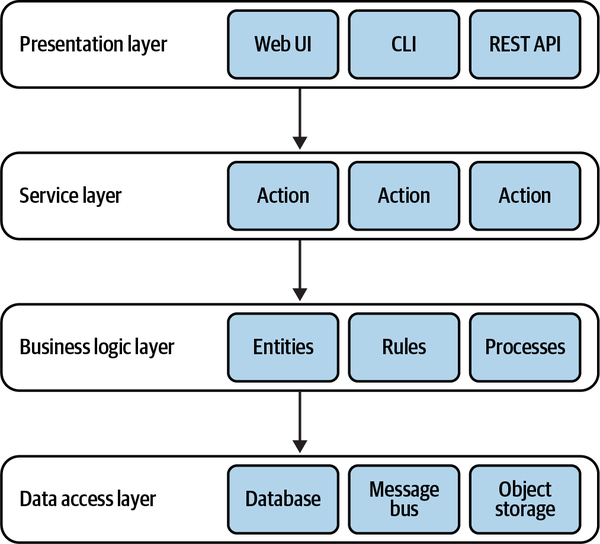

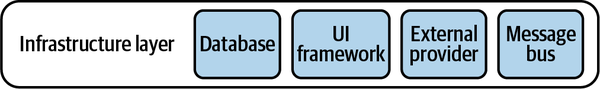

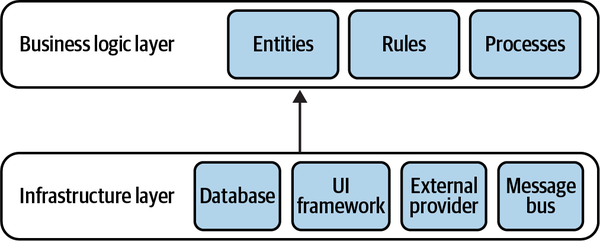

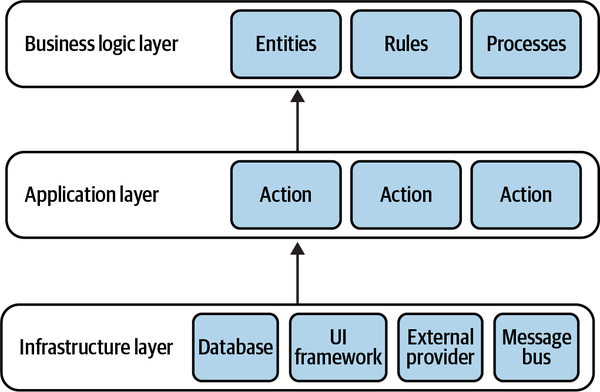

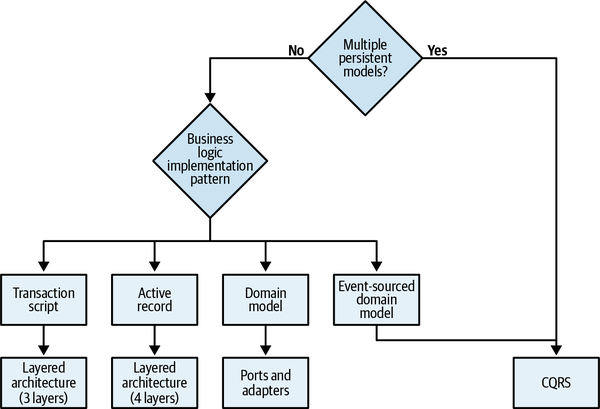

Chapter 8 shifts the focus to a higher level and describes three architectural patterns for structuring components.

-

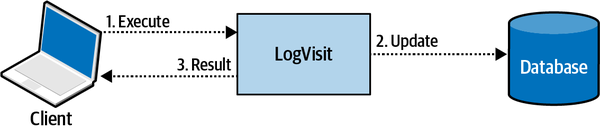

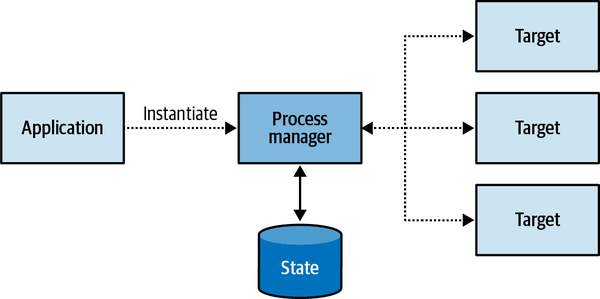

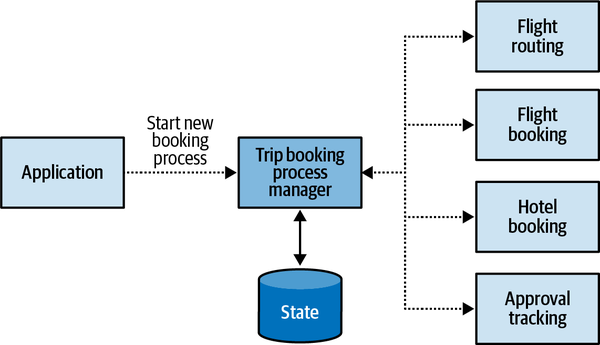

Chapter 9 provides the patterns needed to orchestrate the work of the system’s components.

-

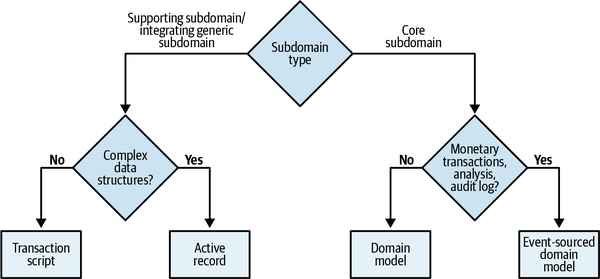

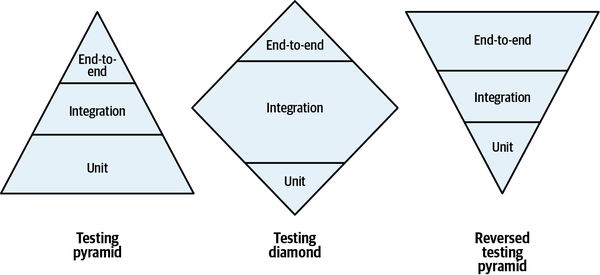

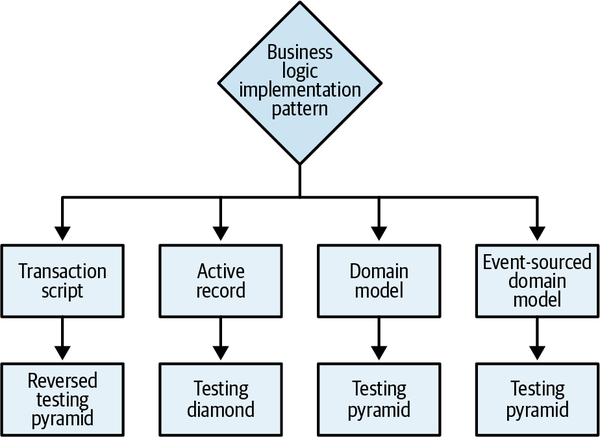

Chapter 10 ties together the patterns discussed in the earlier chapters into a number of simple rules of thumb that streamline the process of making design decisions.

-

Chapter 11 explores software design from the perspective of time and how it is supposed to change and evolve through its lifespan.

-

Chapter 12 introduces EventStorming: a low-tech workshop for effectively sharing knowledge, building shared understanding, and designing software.

-

Chapter 13 addresses the difficulties you may face when introducing domain-driven design to brownfield projects.

-

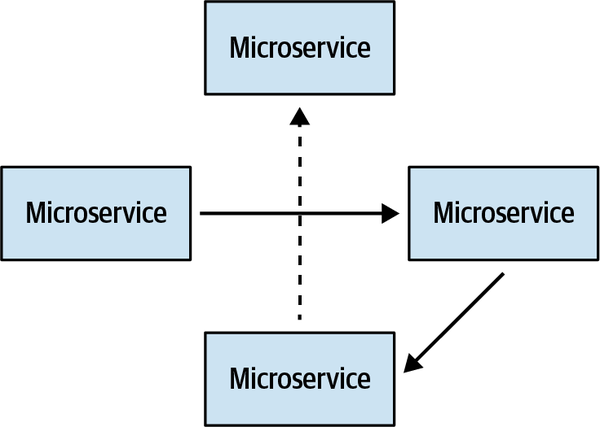

Chapter 14 discusses the relationship between the microservices architectural style and domain-driven design: where they differ and where they complement each other.

-

Chapter 15 explores domain-driven design patterns and tools in the context of the event-driven architecture.

-

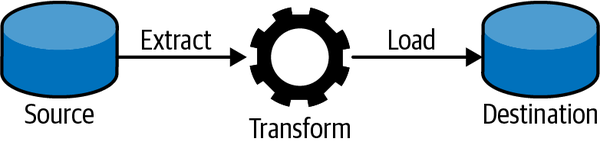

Chapter 16 shifts the discussion from operational systems to analytical data management systems and discusses the interplay between domain-driven design and the data mesh architecture.

All of these chapters end with a number of exercise questions to reinforce the learning.

Example Domain: WolfDesk

WolfDesk provides a help desk tickets management system as a service. If your start-up company needs to provide support to your customers, with WolfDesk’s solution you can get up and running in no time.

WolfDesk uses a different payment model than its competitors. Instead of charging a fee per user, it allows the tenants to set up as many users as needed, and the tenants are charged for the number of support tickets opened per charging period. There is no minimum fee, and there are automatic volume discounts for certain thresholds of monthly tickets: 10% for opening more than 500 tickets, 20% for opening more than 750 tickets, and 30% for opening more than 1,000 tickets per month.

To prevent tenants from abusing the business model, WolfDesk’s ticket lifecycle algorithm ensures that inactive tickets are closed automatically, encouraging customers to open new tickets when further support is needed. Moreover, WolfDesk implements a fraud detection system that analyzes messages and detects cases of unrelated topics being discussed in the same ticket.

To help its tenants streamline the support-related work, WolfDesk has implemented a “support autopilot” feature. The autopilot analyzes new tickets and tries to automatically find a matching solution from the tenant’s ticket history. The functionality allows for further reducing the tickets’ lifespans, encouraging customers to open new tickets for further questions.

WolfDesk incorporates all the security standards and measures to authenticate and authorize its tenants’ users and also allows tenants to configure a single sign-on (SSO) with their existing user management systems.

The administration interface allows tenants to configure the possible values for the tickets’ categories, as well as a list of the tenant’s products that it supports.

To be able to route new tickets to the tenant’s support agents only during their working hours, WolfDesk allows the entry of each agent’s shift schedule.

Since WolfDesk provides its service with no minimal fee, it has to optimize its infrastructure in a way that minimizes the costs of onboarding a new tenant. To do that, WolfDesk leverages serverless computing, which allows it to elastically scale its compute resources based on the operations on active tickets.

Conventions Used in This Book

The following typographical conventions are used in this book:

- Italic

-

Indicates new terms, URLs, email addresses, filenames, and file extensions.

Constant width-

Used for program listings, as well as within paragraphs to refer to program elements such as variable or function names, databases, data types, environment variables, statements, and keywords.

Note

This element signifies a general note.

Using Code Examples

All the code samples presented in the book are implemented in the C# language.

Of course, the concepts and techniques discussed in the book are not limited to the C# language or to the object-oriented programming approach. Everything is relevant for other languages and other programming paradigms. As a result, feel free to implement the book’s samples in your favorite language and share them with me. I’ll be happy to add them to the book’s website.

This book is here to help you get your job done. In general, if example code is offered with this book, you may use it in your programs and documentation. You do not need to contact us for permission unless you’re reproducing a significant portion of the code. For example, writing a program that uses several chunks of code from this book does not require permission. Selling or distributing examples from O’Reilly books does require permission. Answering a question by citing this book and quoting example code does not require permission. Incorporating a significant amount of example code from this book into your product’s documentation does require permission.

We appreciate, but generally do not require, attribution. An attribution usually includes the title, author, publisher, and ISBN. For example: “Learning Domain-Driven Design by Vlad Khononov (O’Reilly). Copyright 2022 Vladislav Khononov, 978-1-098-10013-1.”

If you feel your use of code examples falls outside fair use or the permission given above, feel free to contact us at permissions@oreilly.com.

O’Reilly Online Learning

Note

For more than 40 years, O’Reilly Media has provided technology and business training, knowledge, and insight to help companies succeed.

Our unique network of experts and innovators share their knowledge and expertise through books, articles, and our online learning platform. O’Reilly’s online learning platform gives you on-demand access to live training courses, in-depth learning paths, interactive coding environments, and a vast collection of text and video from O’Reilly and 200+ other publishers. For more information, visit http://oreilly.com.

How to Contact Us

Please address comments and questions concerning this book to the publisher:

- O’Reilly Media, Inc.

- 1005 Gravenstein Highway North

- Sebastopol, CA 95472

- 800-998-9938 (in the United States or Canada)

- 707-829-0515 (international or local)

- 707-829-0104 (fax)

We have a web page for this book, where we list errata, examples, and any additional information. You can access this page at https://oreil.ly/lddd.

Email bookquestions@oreilly.com to comment or ask technical questions about this book.

For news and information about our books and courses, visit http://oreilly.com.

Find us on Facebook: http://facebook.com/oreilly

Follow us on Twitter: http://twitter.com/oreillymedia

Watch us on YouTube: http://youtube.com/oreillymedia

Acknowledgments

Originally, this book was titled “What Is Domain-Driven Design?” and was published as a report in 2019. Learning Domain-Driven Design would not have seen the light of day without the report, and I’m obliged to thank those who made “What Is Domain-Driven Design?” possible: Chris Guzikowski, Ryan Shaw, and Alicia Young.1

This book also wouldn’t have been possible without O’Reilly’s Content Director and Diversity Talent Lead, Melissa Duffield, who championed the project and made it happen. Thank you, Melissa, for all your help!

Jill Leonard was the book’s development editor, project manager, and head coach. Jill’s role in this work cannot be overstated. Jill, thank you so much for all your hard work and help! Extra thanks for keeping me motivated, even when I considered changing my name and hiding in a foreign country.

A huge thanks to the production team for making the book not only writable but readable: Kristen Brown, Audrey Doyle, Kate Dullea, Robert Romano, and Katherine Tozer. For that matter, I want to thank the whole O’Reilly team for the great work you do. It’s a dream come true to be working with you!

Thanks to all the people I interviewed and consulted with: Zsofia Herendi, Scott Hirleman, Trond Hjorteland, Mark Lisker, Chris Richardson, Vaughn Vernon, and Ivan Zakrevsky. Thank you for your wisdom and for being there when I needed help!

Special thanks to the team of reviewers who read through the early drafts and helped me shape the final book: Julie Lerman, Ruth Malan, Diana Montalion, Andrew Padilla, Rodion Promyshlennikov, Viktor Pshenitsyn, Alexei Torunov, Nick Tune, Vasiliy Vasilyuk, and Rebecca Wirfs-Brock. Your support, feedback, and critique helped immensely. Thank you!

I also want to thank Kenny Baas-Schwegler, Alberto Brandolini, Eric Evans, Marco Heimeshoff, Paul Rayner, Mathias Verraes, and the rest of the amazing domain-driven design community. You know who you are. You are my teachers and mentors. Thank you for sharing your knowledge on social media, blogs, and conferences!

I’m most indebted to my dear wife, Vera, for always supporting me in my crazy projects and trying to guard me from things that could distract me from writing. I promise to finally declutter the basement. It is going to happen soon!

Finally, I want to dedicate this book to our beloved Galina Ivanovna Tyumentseva, who supported me so much in this project and whom we sadly lost during the writing of this book. We will always remember you.

#AdoptDontShop

1 Whenever I mention a group of people, the list is in alphabetical order by last name.

Introduction

Software engineering is hard. To be successful at it, we have to learn continuously, whether it’s trying new languages, exploring new technologies, or keeping up with new popular frameworks. However, learning a new JavaScript framework every week is not the hardest aspect of our job. Making sense of new business domains can be far more challenging.

Throughout our careers, it’s not uncommon for us to have to develop software for a diverse range of business domains: financial systems, medical software, online retailers, marketing, and many others. In a sense, that is what differentiates our job from most other professions. People working in other fields are often surprised when they find out how much learning is involved in software engineering, especially when changing workplaces.

Failure to grasp the business domain results in suboptimal implementation of the business software.

Many studies have been conducted to investigate the reasons for the common project failures.2

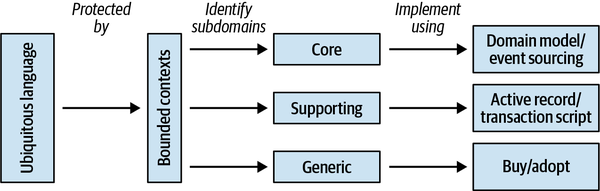

The strategic tools of DDD are used to analyze business domains and strategy, and to foster a shared understanding of the business between the different stakeholders. We will also use this knowledge of the business domain to drive high-level design decisions: decomposing systems into components and defining their integration patterns.

Domain-driven design’s tactical tools address a different aspect of communication issues. DDD’s tactical patterns allow us to write code in a way that reflects the business domain, addresses its goals, and speaks the language of the business.

Both the strategic and tactical patterns and practices of DDD align software design with its business domain. That’s where the name comes from: (business) domain-driven (software) design.

Domain-driven design won’t make it possible to install the knowledge of new JavaScript libraries directly into your brain, like in The Matrix. However, it will make you a more effective software engineer by alleviating the process of making sense of business domains and guiding the design decisions according to the business strategy. As you will learn in the book’s later chapters, the tighter the connection between the software design and its business strategy is, the easier it will be to maintain and evolve the system to meet the future needs of the business, ultimately leading to more successful software projects.

Let’s start our DDD journey by exploring the strategic patterns and practices.

2 See, for example, Kaur, Rupinder, and Dr. Jyotsna Sengupta (2013), “Software Process Models and Analysis on Failure of Software Development Projects,” https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1306/1306.1068.pdf. See also Sudhakar, Goparaju Purna (2012), “A Model of Critical Success Factors for Software Projects.” Journal of Enterprise Information Management 25(6), 537–558.

Part I. Strategic Design

There is no sense in talking about the solution before we agree on the problem, and no sense talking about the implementation steps before we agree on the solution.

Efrat Goldratt-Ashlag1

The domain-driven design (DDD) methodology can be divided into

We will begin our journey by exploring domain-driven design patterns and principles of strategic design:

- InChapter 1, you will learn to analyze a company’s business strategy: what value it provides to its consumers and how it competes with other companies in the industry. We will identify finer-grained business building blocks, evaluate their strategic value, and analyze how they affect different software design decisions.

-

Chapter 2 introduces domain-driven design’s essential practice for gaining an understanding of the business domain: the ubiquitous language. You will learn how to cultivate a ubiquitous language and use it to foster a shared understanding among all project-related stakeholders.

-

Chapter 3 discusses another domain-driven design core tool: the bounded context pattern. You will learn why this tool is essential for cultivating a ubiquitous language and how to use it to transform discovered knowledge into a model of the business domain. Ultimately, we will leverage bounded contexts to design coarse-grained components of the software system.

-

In Chapter 4, you will learn technical and social constraints that affect how system components can be integrated, and integration patterns that address different situations and limitations. We will discuss how each pattern influences collaboration among software development teams and the design of the components’ APIs.

The chapter closes by introducing the context map: a graphical notation that plots communication between the system’s bounded contexts and provides a bird’s-eye view of the project’s integration and collaboration landscapes.

1 Goldratt-Ashlag, E. (2010). “The Layers of Resistance—The Buy-In Process According to TOC.”

Chapter 1. Analyzing Business Domains

If you are anything like me, you love writing code: solving complex problems, coming up with elegant solutions, and constructing whole new worlds by carefully crafting their rules, structures, and behavior. I believe that’s what interested you in domain-driven design (DDD): you want to be better at your craft. This chapter, however, has nothing to do with writing code. In this chapter, you will learn

When I teach this material in my domain-driven design classes, many students actually ask, “Do we need to know this material? We are writing software, not running businesses.” The answer to their question is a resounding “yes.” To design and build an effective solution, you have to understand the problem. The problem, in our context, is the software system we have to build. To understand the problem, you have to understand the context within which it exists—the organization’s business strategy, and what value it seeks to gain by building the software.

In this chapter, you will learn domain-driven design tools for analyzing a company’s business domain and its structure: its core, supporting, and generic subdomains. This material is the groundwork for designing software. In the remaining chapters, you will learn the different ways these concepts affect software design.

What Is a Business Domain?

-

FedEx provides courier delivery.

-

Starbucks is best known for its coffee.

-

Walmart is one of the most widely recognized retail establishments.

A company can operate in multiple business domains. For example, Amazon provides both retail and cloud computing services. Uber is a rideshare company that also provides food delivery and bicycle-sharing services.

It’s important to note that companies may change their business domains often. A canonical example of this is Nokia, which over the years has operated in fields as diverse as wood processing, rubber manufacturing, telecommunications, and mobile communications.

What Is a Subdomain?

Types of Subdomains

Just as a software system comprises various architectural components—databases, frontend applications, backend services, and others—subdomains bear different strategic/business values. Domain-driven design distinguishes between three types of subdomains: core, generic, and supporting. Let’s see how they differ from a company strategy point of view.

Core subdomains

Uber’s core subdomains affect its bottom line. This is how the company differentiates itself from its competitors. This is the company’s strategy for providing better service to its customers and/or maximizing its profitability. To maintain a competitive advantage, core subdomains involve inventions, smart optimizations, business know-how, or other intellectual property.

Complexity

Sources of competitive advantage

Consider, for example, a jewelry maker selling its products online. The online shop is important, but it’s not a core subdomain. The jewelry design is. The company can use an existing off-the-shelf online shop engine, but it cannot outsource the design of its jewelry. The design is the reason customers buy the jewelry maker’s products and remember the brand.

Generic subdomains

Generic subdomains are business activities that

For example, most systems need to authenticate and authorize their users. Instead of inventing a proprietary authentication mechanism, it makes more sense to use an existing solution. Such a solution is likely to be more reliable and secure since it has already been tested by many other companies that have the same needs.

Going back to the example of a jewelry maker selling its products online, jewelry design is a core subdomain, but the online shop is a generic subdomain. Using the same online retail platform—the same generic solution—as its competitors would not impact the jewelry maker’s competitive advantage.

Supporting subdomains

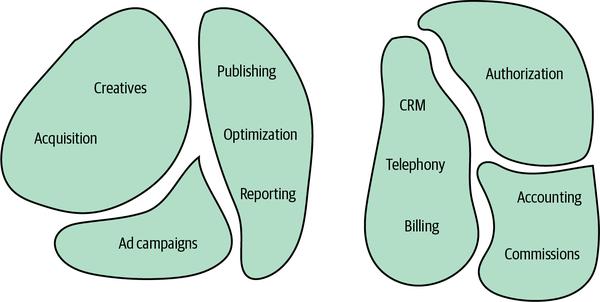

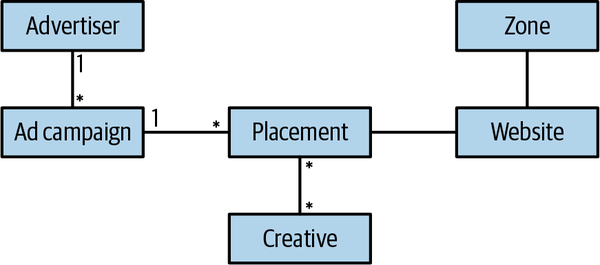

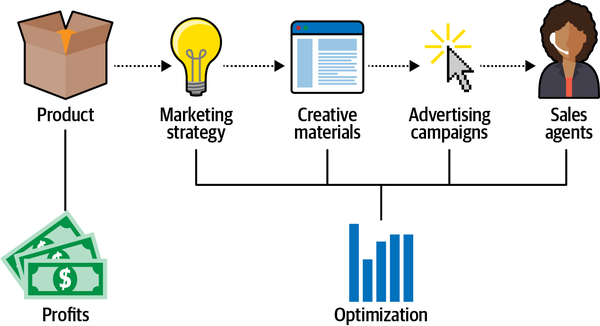

For example, consider an online advertising company whose core subdomains include matching ads to visitors, optimizing the ads’ effectiveness, and minimizing the cost of ad space. However, to achieve success in these areas, the company needs to catalog its creative materials. The way the company stores and indexes its physical creative materials, such as banners and landing pages, does not impact its profits. There is nothing to invent or optimize in that area. On the other hand, the creative catalog is essential for implementing the company’s advertising management and serving systems. That makes the content cataloging solution one of the company’s supporting subdomains.

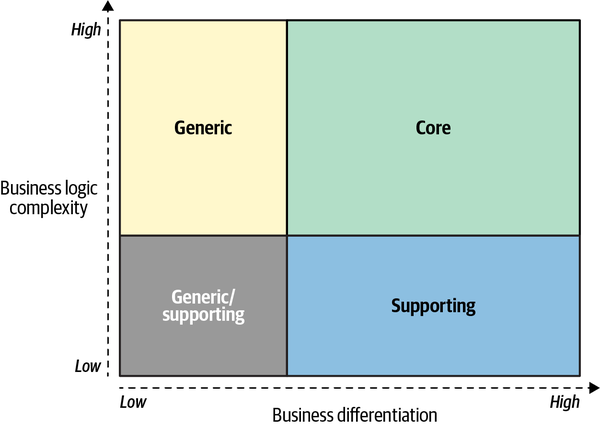

Comparing Subdomains

Competitive advantage

The more complex the problems a company is able to tackle,

Complexity

From a knowledge availability perspective, generic subdomains are “known unknowns.” These are the things that you know you don’t know. Furthermore, this knowledge is readily available. You can either use industry-accepted best practices or, if needed, hire a consultant specializing in the area to help design a custom solution.

At times it may be challenging to differentiate between core and supporting subdomains. Complexity is a useful guiding principle. Ask whether the subdomain in question can be turned into a side business. Would someone pay for it on its own? If so, this is a core subdomain. Similar reasoning applies for differentiating supporting and generic subdomains: would it be simpler and cheaper to hack your own implementation, rather than integrating an external one? If so, this is a supporting subdomain.

Figure 1-1. The business differentiation and business logic complexity of the three types of subdomains

Volatility

As mentioned previously, core subdomains can change often. If a

Despite having existing solutions, generic subdomains can change over time. The changes can come in the form of security patches, bug fixes, or entirely new solutions to the generic problems.

Solution strategy

It would also be unwise to outsource the implementation of a core subdomain. It is a strategic investment. Cutting corners on a core subdomain is not only risky in the short term but can have fatal consequences in the long run: for example, unmaintainable codebases that cannot support the company’s goals and objectives. The organization’s most skilled talent should be assigned to work on its core subdomains. Furthermore, implementing core subdomains in-house allows the company to make changes and evolve the solution more quickly, and therefore build the competitive advantage in less time.

Supporting subdomains do not require elaborate design patterns or other advanced engineering techniques. A rapid application development framework will suffice to implement the business logic without introducing accidental complexities.

From a staffing perspective, supporting subdomains do not require highly skilled technical aptitude and provide a great opportunity to train up-and-coming talent. Save the engineers on your team who are experienced in tackling complex challenges for the core subdomains. Finally, the simplicity of the business logic makes supporting subdomains a good candidate for outsourcing.

| Subdomain type | Competitive advantage | Complexity | Volatility | Implementation | Problem |

| Core | Yes | High | High | In-house | Interesting |

| Generic | No | High | Low | Buy/adopt | Solved |

| Supporting | No | Low | Low | In-house/outsource | Obvious |

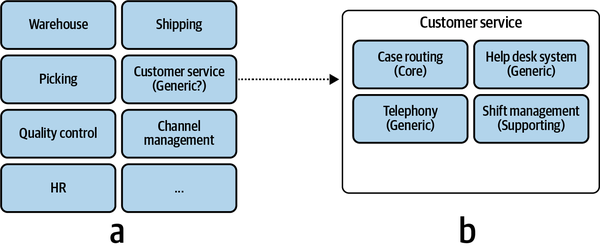

Identifying Subdomain Boundaries

A good starting point is the company’s departments and other organizational units. For example, an online retail shop might include warehouse, customer service, picking, shipping, quality control, and channel management departments, among others. These, however, are relatively coarse-grained areas of activity. Take, for example, the customer service department. It’s reasonable to assume that it would be a supporting, or even a generic subdomain, as this function is often outsourced to third-party vendors. But is this information enough for us to make sound software design decisions?

Distilling subdomains

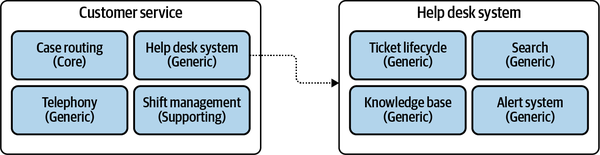

Figure 1-2. Analyzing the inner workings of a suspectedly generic subdomain to find the finer-grained core subdomain, supporting subdomain, and two generic subdomains

On the other hand, we cannot drill down indefinitely, looking for insights at lower and lower levels of granularity. When should you stop?

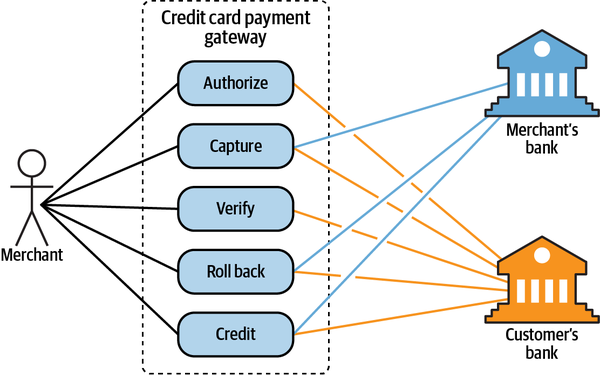

Subdomains as coherent use cases

From a technical perspective, subdomains resemble sets of

We can use the definition of “subdomains as a set of coherent use cases” as a guiding principle for when to stop looking for finer-grained subdomains.

Figure 1-3. Use case diagram of a credit card payment subdomain

Should you always strive to identify such laser-focused subdomain boundaries? It is definitely necessary for core subdomains. Core subdomains are the most important, volatile, and complex. It’s essential that we distill them as much as possible since that will allow us to extract all generic and supporting functionalities and invest the effort on a much more focused functionality.

The distillation can be somewhat relaxed for supporting and generic subdomains. If drilling down further doesn’t unveil any new insights that can help you make software design decisions, it can be a good place to stop. This can happen, for example, when all of the finer-grained subdomains are of the same type as the original subdomain.

Figure 1-4. Distilling the help desk system subdomain, revealing generic inner components

Another important question to consider when identifying the subdomains is whether we need all of them.

Focus on the essentials

Subdomains are a tool that alleviates the process of making

When looking for subdomains, it’s important to identify business functions that are not related to software, acknowledge them as such, and focus on aspects of the business that are relevant to the software system you are working on.

Domain Analysis Examples

Disclaimer: of course, we cannot identify all the subdomains involved in each business domain by reading such a short description. That said, it is enough to train you to identify and categorize the available subdomains.

Gigmaster

Gigmaster’s users are conscious of their privacy. Hence, all users’ personal information is encrypted. Moreover, to ensure that users’ guilty pleasures won’t leak out under any circumstances, the company’s recommendation algorithm works exclusively on anonymized data.

To improve the app’s recommendations, a new module was implemented. It allows users to log gigs they attended in the past, even if the tickets weren’t purchased through Gigmaster.

Business domain and subdomains

Gigmaster’s business domain is ticket sales. That’s the service it provides to its customers.

Core subdomains

Gigmaster’s main competitive advantage is its recommendation engine. The company also takes its users’ privacy seriously and works only on anonymized data. Finally, although not mentioned explicitly, we can infer that the mobile app’s user experience is crucial as well. As such, Gigmaster’s core subdomains are:

-

Recommendation engine

-

Data anonymization

-

Mobile app

Generic subdomains

We can identify and infer the following generic subdomains:

-

Encryption, for encrypting all data

-

Accounting, since the company is in the sales business

-

Clearing, for charging its customers

-

Authentication and authorization, for identifying its users

Supporting subdomains

Finally, the following are the supporting subdomains. Here the business logic is simple and resembles ETL processes or CRUD interfaces:

-

Integration with music streaming services

-

Integration with social networks

-

Attended-gigs module

Design decisions

Knowing the subdomains at play and the differences between their types, we can already make several strategic design decisions:

-

The recommendation engine, data anonymization, and mobile app have to be implemented in-house using the most advanced engineering tools and techniques. These modules are going to change the most often.

-

Off-the-shelf or open source solutions should be used for data encryption, accounting, clearing, and authentication.

- Integration with streaming services and social networks, as well as the module for attended gigs, can be outsourced.

BusVNext

A BusVNext customer can order a ride through the mobile app. At the scheduled departure time, a nearby bus’s route will be adjusted on the fly to pick up the customer at the specified departure time.

From time to time, BusVNext issues special discounts, both to attract new customers and to level the demand for rides over peak and off-peak hours.

Business domain and subdomains

BusVNext provides optimized bus rides to its customers. The business domain is public transportation.

Core subdomains

BusVNext’s primary competitive advantage is its routing algorithm that takes a stab at solving a complex problem (“travelling salesman”) while prioritizing different business goals: for example, decreasing pickup times, even if it will increase overall ride lengths.

We also saw that the rides data is continuously analyzed for new insights into customers’ behaviors. These insights allow the company to increase its profits by optimizing the routing algorithm. Finally, BusVNext’s applications for its customers and its drivers have to be easy to use and provide a convenient user interface.

Managing a fleet is not trivial. Buses may experience technical issues or require maintenance. Ignoring these may result in financial losses and a reduced level of service.

Hence, BusVNext’s core subdomains are:

-

Routing

-

Analysis

-

Mobile app user experience

-

Fleet management

Generic subdomains

The routing algorithm also uses traffic data and alerts provided by third-party companies—a generic subdomain. Moreover, BusVNext accepts payments from its customers, so it has to implement accounting and clearing functionalities. BusVNext’s generic subdomains are:

-

Traffic conditions

-

Accounting

-

Billing

-

Authorization

Supporting subdomains

The module for managing promos and discounts supports the company’s core business. That said, it’s not a core subdomain by itself. Its management interface resembles a simple CRUD interface for managing active coupon codes. Therefore, this is a typical supporting subdomain.

Design decisions

Knowing the subdomains at play and the differences between their types, we can already make a number of strategic design decisions:

-

The routing algorithm, data analysis, fleet management, and app usability have to be implemented in-house using the most elaborate technical tools and patterns.

-

Implementation of the promotions management module can be outsourced.

-

Identifying traffic conditions, authorizing users, and managing financial records and transactions can be offloaded to external service providers.

Who Are the Domain Experts?

Now that we have a clear understanding of business domains and subdomains,

The domain experts are neither the analysts gathering the requirements nor the engineers designing the system. Domain experts represent the business. They are the people who identified the business problem in the first place and from whom all business knowledge originates. Systems analysts and engineers are transforming their mental models of the business domain into software requirements and source code.

As a rule of thumb, domain experts are either the people coming up with requirements or the software’s end users. The software is supposed to solve their problems.

The domain experts’ expertise can have different scopes. Some subject matter experts will have a detailed understanding of how the entire business domain operates, while others will specialize in particular subdomains. For example, in an online advertising agency, the domain experts would be campaign managers, media buyers, analysts, and other business stakeholders.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we covered domain-driven design tools for making sense of a company’s business activity. As you’ve seen, it all starts with the business domain: the area the business operates in and the service it provides to its clients.

You also learned about the different building blocks required to achieve success in a business domain and differentiate the company from its competitors:

- Core subdomains

- The interesting problems. These are the activities the company is performing differently from its competitors and from which it gains its competitive advantage.

- Generic subdomains

- The solved problems. These are the things all companies are doing in the same way. There is no room or need for innovation here; rather than creating in-house implementations, it’s more cost-effective to use existing solutions.

- Supporting subdomains

- The problems with obvious solutions. These are the activities the company likely has to implement in-house, but that do not provide any competitive advantage.

Finally, you learned that domain experts are the business’s subject matter experts. They have in-depth knowledge of the company’s business domain or one or more of its subdomains and are critical to a project’s success.

Exercises

-

Which of the subdomains provide(s) no competitive advantage?

-

Core

-

Generic

-

Supporting

-

B and C

-

-

For which subdomain might all competitors use the same solutions?

-

Core.

-

Generic.

-

Supporting.

-

None of the above. The company should always differentiate itself from its competitors.

-

-

Which subdomain is expected to change the most often?

-

Core.

-

Generic.

-

Supporting.

-

There is no difference in volatility of the different subdomain types.

-

-

What is WolfDesk’s business domain?

-

What is/are WolfDesk’s core subdomain(s)?

-

What is/are WolfDesk’s supporting subdomain(s)?

-

What is/are WolfDesk’s generic subdomain(s)?

Chapter 2. Discovering Domain Knowledge

It’s developers’ (mis)understanding, not domain experts’ knowledge, that gets released in production.

Alberto Brandolini

In the previous chapter, we started exploring business domains. You learned how to identify a company’s business domains, or areas of activity, and analyze its strategy to compete in them; that is, its business subdomains’ boundaries and types.

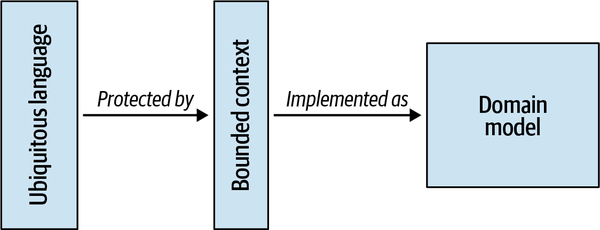

This chapter continues the topic of business domain analysis but in a different dimension: depth. It focuses on what happens inside a subdomain: its business function and logic. You will learn the domain-driven design tool for effective communication and knowledge sharing: the ubiquitous language. Here we will use it to learn the intricacies of business domains. Later in the book we will use it to model and implement their business logic in software.

Business Problems

Subdomains are finer-grained problem domains whose goal

Knowledge Discovery

To be effective, the software has to mimic the

Communication

It’s safe to say that almost all software projects require the collaboration of stakeholders in different roles: domain experts, product owners, engineers, UI and UX designers, project managers, testers, analysts, and others. As in any collaborative effort, the outcome depends on how well all those parties can work together. For example, do all stakeholders agree on what problem is being solved? What about the solution they are building—do they hold any conflicting assumptions about its functional and nonfunctional requirements? Agreement and alignment on all project-related matters are essential to a project’s success.

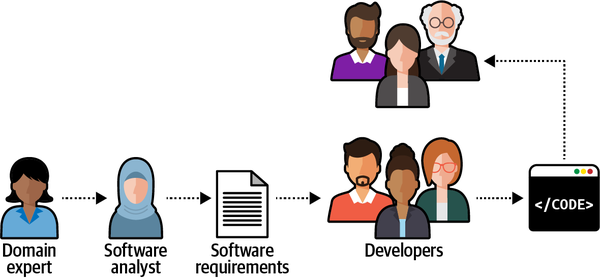

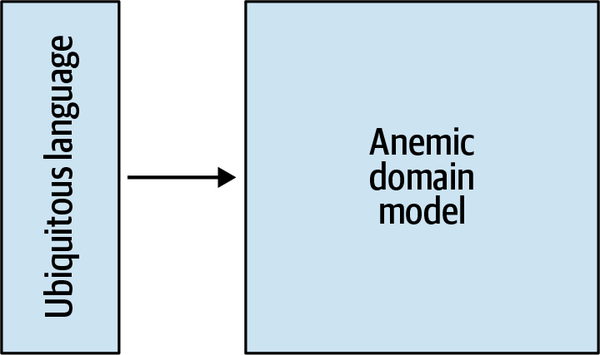

Figure 2-1. Knowledge sharing flow in a software project

During the traditional software development lifecycle, the domain knowledge is “translated” into an

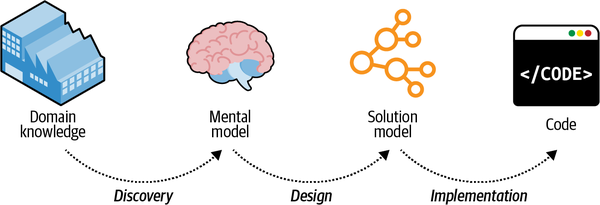

Figure 2-2. Model transformations

Such a software development process resembles the children’s game Telephone:3 the message, or domain knowledge, often becomes distorted. The information leads to software engineers implementing the wrong solution, or the right solution but to the wrong problems. In either case, the outcome is the same: a failed software project.

Domain-driven design proposes a better way to get the knowledge from domain experts to software engineers: by using a ubiquitous language.

What Is a Ubiquitous Language?

Although this notion is borderline common sense, as Voltaire said, “common sense is not so common.” The traditional software development lifecycle implies the following translations:

-

Domain knowledge into an analysis model

-

Analysis model into requirements

-

Requirements into system design

-

System design into source code

Instead of continuously translating domain knowledge, domain-driven design calls for cultivating a single language for describing the business domain: the ubiquitous language.

All project-related stakeholders—software engineers, product owners, domain experts, UI/UX designers—should use the ubiquitous language when describing the business domain. Most importantly, domain experts must be comfortable using the ubiquitous language when reasoning about the business domain; this language will represent both the business domain and the domain experts’ mental models.

Only through the continuous use of the ubiquitous language and its terms can a shared understanding among all of the project’s stakeholders be cultivated.

Language of the Business

It’s crucial to emphasize that the ubiquitous language is the language of the business. As such, it should consist of business domain–related terms only. No technical jargon! Teaching business domain experts about singletons and abstract factories is not your goal. The ubiquitous language aims to frame the domain experts’ understanding and mental models of the business domain in terms that are easy to understand.

Scenarios

Let’s say we are working on an advertising campaign management system. Consider the following statements:

-

An advertising campaign can display different creative materials.

-

A campaign can be published only if at least one of its placements is active.

-

Sales commissions are accounted for after transactions are approved.

All of these statements are formulated in the language of the business. That is, they reflect the domain experts’ view of the business domain.

On the other hand, the following statements are strictly technical and thus do not fit the notion of the ubiquitous language:

-

The advertisement iframe displays an HTML file.

-

A campaign can be published only if it has at least one associated record in the active-placements table.

-

Sales commissions are based on correlated records from the transactions and approved-sales tables.

These latter statements are purely technical and will be unclear to domain experts. Suppose engineers are only familiar with this technical, solution-oriented view of the business domain. In that case, they won’t be able to completely understand the business logic or why it operates the way it does, which will limit their ability to model and implement an effective solution.

Consistency

The ubiquitous language must be precise and consistent. It should eliminate the need for assumptions and should make the business domain’s logic explicit.

Since ambiguity hinders communication, each term of the ubiquitous language should have one and only one meaning. Let’s look at a few examples of unclear terminology and how it can be improved.

Ambiguous terms

Let’s say that in some business domain, the term policy has multiple meanings: it can mean a regulatory rule or an insurance contract. The exact meaning can be worked out in human-to-human interaction, depending on the context. Software, however, doesn’t cope well with ambiguity, and it can be cumbersome and challenging to model the “policy” entity in code.

Ubiquitous language demands a single meaning for each term, so “policy” should be modeled explicitly using the two terms regulatory rule and insurance contract.

Synonymous terms

Two terms cannot be used interchangeably in a ubiquitous language. For example, many systems use the term user. However, a careful examination of the domain experts’ lingo may reveal that user and other terms are used interchangeably: for example, user, visitor, administrator, account, etc.

Synonymous terms can seem harmless at first. However, in most cases, they denote different concepts. In this example, both visitor and account technically refer to the system’s users; however, in most systems, unregistered and registered users represent different roles and have different behaviors. For example, the “visitors” data is used mainly for analysis purposes, whereas “accounts” actually uses the system and its functionality.

Model of the Business Domain

Now let’s look at the ubiquitous language from a different perspective: modeling.

What Is a Model?

A model is a simplified representation of a thing orphenomenon that intentionally emphasizes certain aspects while ignoring others. Abstraction with a specific use in mind.Rebecca Wirfs-Brock

A model is not a copy of the real world but a human construct that helps us make sense of real-world systems.

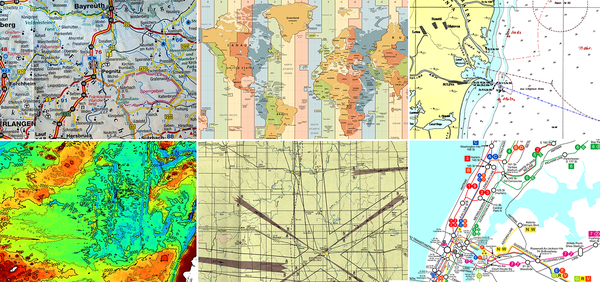

Figure 2-3. Different types of maps displaying different models of the earth: roads, time zones, nautical navigation, terrain, aeronautical navigation, and subway routes.

None of these maps represents all the details of our planet. Instead, each map contains just enough data to support its particular purpose: the problem it is supposed to solve.

Effective Modeling

All models have a purpose, and an effective model contains only the details

Modeling the Business Domain

When cultivating a ubiquitous language, we are effectively

Effective communication between engineering teams and domain experts is vital. The importance of this communication grows with the complexity of the business domain. The more complex the business domain is, the harder it is to model and implement its business logic in code. Even a slight misunderstanding of a complicated business domain, or its underlying principles, will inadvertently lead to an implementation prone to severe bugs. The only reliable way to verify a business domain’s understanding is to converse with domain experts and do it in the language they understand: the language of the business.

Continuous Effort

All stakeholders should consistently use the ubiquitous language in all project-related communications to spread knowledge about and foster a shared understanding of the business domain. The language should be continuously reinforced throughout the project: requirements, tests, documentation, and even the source code itself should use this language.

Most importantly, cultivation of a ubiquitous language is an ongoing process. It should be constantly validated and evolved. Everyday use of the language will, over time, reveal deeper insights into the business domain. When such breakthroughs happen, the ubiquitous language must evolve to keep pace with the newly acquired domain knowledge.

Tools

It’s important to make glossary maintenance a shared effort. When a ubiquitous language is changed, all team members should be encouraged to go ahead and update the glossary. That’s contrary to a centralized approach, in which only team leaders or architects are in charge of maintaining the glossary.

Scenario:Notify the agent about a new support caseGivenVincent Jules submits a new support case saying:"""I need help configuring AWS Infinidash"""Whenthe ticket is assigned to Mr. WolfThenthe agent receives a notification about the new ticket

Managing a Gherkin-based test suite can be challenging at times, especially at the early stages of a project. However, it is definitely worth it for complex business domains.

Finally, there are even static code analysis tools that can verify the usage of a ubiquitous language’s terms. A notable example for such a tool is NDepend.

While these tools are useful, they are secondary to the actual use of a ubiquitous language in day-to-day interactions. Use the tools to support the management of the ubiquitous language, but don’t expect the documentation to replace the actual usage.

As the Agile Manifesto says, “Individuals and interactions over processes and tools.” Challenges

In theory, cultivating a ubiquitous language sounds like a

simple, straightforward process. In practice, it isn’t. The only reliable way to gather domain knowledge is to converse with domain experts. Quite often, the most important knowledge is tacit. It’s not documented or codified but resides only in the minds of domain experts. The only way to access it is to ask questions. As you gain experience in this practice, you will notice that frequently, this process involves not merely discovering knowledge that is already there, but rather co-creating the model in tandem with domain experts. There may be ambiguities and even white spots in domain experts’ own understanding of the business domain; for example, defining only the “happy path” scenarios but not considering edge cases that challenge the accepted assumptions. Furthermore, you may encounter business domain concepts that lack explicit definitions. Asking questions about the nature of the business domain often makes such implicit conflicts and white spots explicit. This is especially common for core subdomains. In such a case, the learning process is mutual—you are helping the domain experts better understand their field.

When introducing domain-driven design practices to a brownfield project, you will notice that there is already a formed language for describing the business domain, and that the stakeholders use it. However, since DDD principles do not drive that language, it won’t necessarily reflect the business domain effectively. For example, it may use technical terms, such as database table names. Changing a language that is already being used in an organization is not easy. The essential tool in such a situation is patience. You need to make sure the correct language is used where it’s easy to control it: in the documentation and source code.

Finally, the question about the ubiquitous language that I am asked often at conferences is what language should we use if the company is not in an English-speaking country. My advice is to at least use English nouns for naming the business domain’s entities. This will alleviate using the same terminology in code. Conclusion

Effective communication and knowledge sharing are crucial for a successful software project. Software engineers have to understand the business domain in order to design and build a software solution.

Domain-driven design’s ubiquitous language is an effective tool for bridging the knowledge gap between domain experts and software engineers. It fosters communication and knowledge sharing by cultivating a shared language that can be used by all the stakeholders throughout the project: in conversations, documentation, tests, diagrams, source code, and so on.

To ensure effective communication, the ubiquitous language has to eliminate ambiguities and implicit assumptions. All of a language’s terms have to be consistent—no ambiguous terms and no synonymous terms.

Cultivating a ubiquitous language is a continuous process. As the project evolves, more domain knowledge will be discovered. It’s important for such insights to be reflected in the ubiquitous language.

Tools such as wiki-based glossaries and Gherkin tests can greatly alleviate the process of documenting and maintaining a ubiquitous language. However, the main prerequisite for an effective ubiquitous language is usage: the language has to be used consistently in all project-related communications.

Exercises

-

Who should be able to contribute to the definition of a ubiquitous language?

-

Domain experts

-

Software engineers

-

End users

-

All of the project’s stakeholders

-

Where should a ubiquitous language be used?

-

In-person conversations

-

Documentation

-

Code

-

All of the above

- Please review the description of the fictional WolfDesk company in the Preface. What business domain terminology can you spot in the description?

-

Consider a software project you are working on at the moment or worked on in the past:

-

Try to come up with concepts of the business domain that you could use in conversations with domain experts.

-

Try to identify examples of inconsistent terms: business domain concepts that have either different meanings or identical concepts represented by different terms.

-

Have you encountered software development inefficiencies that resulted from poor communication?

-

Assume you are working on a project and you notice that domain experts from different organizational units use the same term, for example, policy, to describe unrelated concepts of the business domain.

The resultant ubiquitous language is based on domain experts’ mental models but fails to fulfill the requirement of a term having a single meaning.

Before you continue to the next chapter, how would you address such a conundrum?

1 Brandolini, Alberto. (n.d.). Introducing EventStorming. Leanpub.

2 Sudhakar, Goparaju Purna. (2012). “A Model of Critical Success Factors for Software Projects.” Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 25(6), 537–558.

3 Players form a line, and the first player comes up with a message and whispers it into the ear of the second player. The second player repeats the message to the third player, and so on. The last player announces the message they heard to the entire group. The first player then compares the original message with the final version. Although the objective is to communicate the same message, it usually gets garbled and the last player receives a message that is significantly different from the original one.

4 Edsger W. Dijkstra, “The Humble Programmer”.

5 But please don’t fall into the trap of thinking that domain experts will write Gherkin tests.

Chapter 3. Managing Domain Complexity

As you saw in the previous chapter, to ensure a project’s success

Inconsistent Models

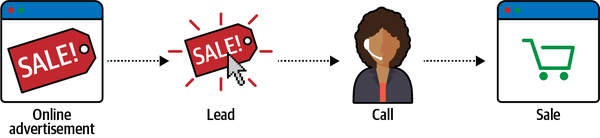

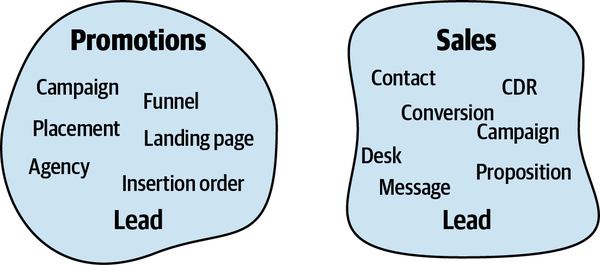

Figure 3-1. Example business domain: telemarketing company

An examination of the domain experts’ language reveals a peculiar observation. The term lead has different meanings in the marketing and sales departments:

- Marketing department

- For the marketing people, a lead represents a notification that somebody is interested in one of the products. The event of receiving the prospective customer’s contact details is considered a lead.

- Sales department

- In the context of the sales department, a lead is a much more complex entity. It represents the entire lifecycle of the sales process. It’s not a mere event, but a long-running process.

How do we formulate a ubiquitous language in the case of this telemarketing company?

On the one hand, we know the ubiquitous language has to be consistent—each term should have one meaning. On the other hand, we know the ubiquitous language has to reflect the domain experts’ mental models. In this case, the mental model of the “lead” is inconsistent among the domain experts in the sales and marketing departments.

This ambiguity doesn’t present that much of a challenge in person-to-person communications. Indeed, communication can be more challenging among people from different departments, but it’s easy enough for humans to infer the exact meaning from the interaction’s context.

However, it is more difficult to represent such a divergent model of the business domain in software. Source code doesn’t cope well with ambiguity. If we were to bring the sales department’s complicated model into marketing, it would introduce complexity where it’s not needed— far more detail and behavior than marketing people need for optimizing advertising campaigns. But if we were to try to simplify the sales model according to the marketing world view, it wouldn’t fit the sales subdomain’s needs, because it’s too simplistic for managing and optimizing the sales process. We’d have an overengineered solution in the first case and an under-engineered one in the second.

How do we solve this catch-22?

The traditional solution to this problem is to design a single model that can be used for all kinds of problems. Such models result in enormous entity relationship diagrams (ERDs) spanning whole office walls. Is Figure 3-2 an effective model?

Figure 3-2. Enterprise-wide entity relationship diagram

As the saying goes, “jack of all trades, master of none.” Such models are supposed to be suitable for everything but eventually are effective for nothing. No matter what you do, you are always facing complexity: the complexity of filtering out extraneous details, the complexity of finding what you do need, and most importantly, the complexity of keeping the data in a consistent state.

Another solution would be to prefix the problematic term with a definition of the context: “marketing lead” and “sales lead.” That would allow the implementation of the two models in code. However, this approach has two main disadvantages. First, it induces cognitive load. When should each model be used? The closer the implementations of the conflicting models are, the easier it is to make a mistake. Second, the implementation of the model won’t be aligned with the ubiquitous language. No one would use the prefixes in conversations. People don’t need this extra information; they can rely on the conversation’s context.

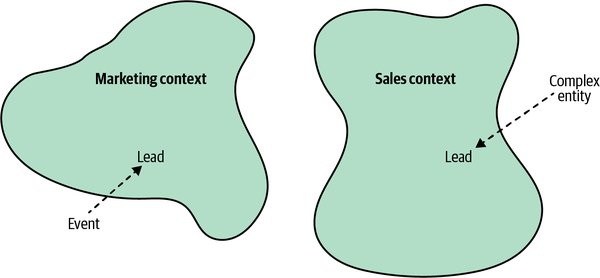

Let’s turn to the domain-driven design pattern for tackling such scenarios: the bounded context pattern.

What Is a Bounded Context?

Figure 3-3. Tackling inconsistencies in the ubiquitous language by splitting it into bounded contexts

In a sense, terminology conflicts and implicit contexts are an inherent part of any decent-sized business. With the bounded context pattern, the contexts are modeled as an explicit and integral part of the business domain.

Model Boundaries

As we discussed in the previous chapter, a model is not a

Let’s go back to the example of maps as models. We saw that each map has its specific context—aerial, nautical, terrain, subway, and so on. A map is useful and consistent only within the scope of its specific purpose.

Just as a subway map is useless for nautical navigation, a ubiquitous language in one bounded context can be completely irrelevant to the scope of another bounded context. Bounded contexts define the applicability of a ubiquitous language and of the model it represents. They allow defining distinct models according to different problem domains. In other words, bounded contexts are the consistency boundaries of ubiquitous languages. A language’s terminology, principles, and business rules are only consistent inside its bounded context.

Ubiquitous Language Refined

Instead, a ubiquitous language is ubiquitous only in the boundaries of its bounded context. The language is focused on describing only the model that is encompassed by the bounded context. As a model cannot exist without a problem it is supposed to address, a ubiquitous language cannot be defined or used without an explicit context of its applicability.

Scope of a Bounded Context

Figure 3-4. Smaller bounded contexts

Defining the scope of a ubiquitous language—its bounded context—is a strategic design decision.

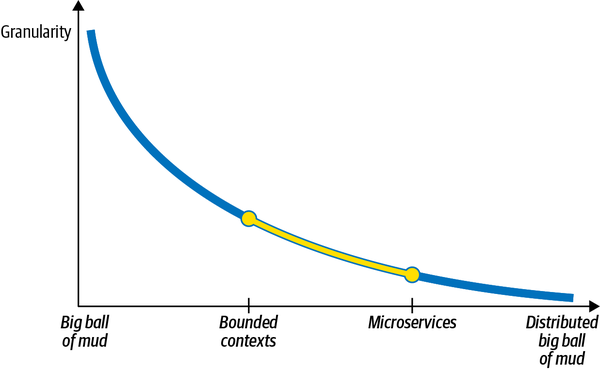

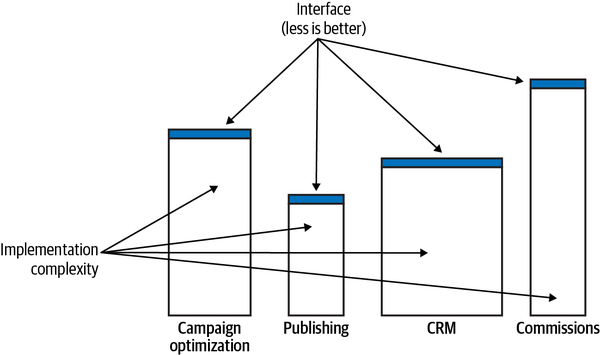

A bounded context’s size, by itself, is not a deciding factor. Models shouldn’t necessarily be big or small. Models need to be useful. The wider the boundary of the ubiquitous language is, the harder it is to keep it consistent. It may be beneficial to divide a large ubiquitous language into smaller, more manageable problem domains, but striving for small bounded contexts can backfire too. The smaller they are, the more integration overhead the design induces.

Hence, the decision for how big your bounded contexts should depend on the specific problem domain. Sometimes, using a wide boundary will be clearer, while at other times, decomposing it further will make more sense.

The reasons for extracting finer-grained bounded contexts out of a larger one include constituting new software engineering teams or addressing some of the system’s nonfunctional requirements; for example, when you need to separate the development lifecycles of some of the components originally residing in a single bounded context. Another common reason for extracting one functionality is the ability to scale it independently from the rest of the bounded context’s functionalities.

We’ll discuss the topic of continuously optimizing the bounded contexts’ boundaries further in Chapters 8 and 10

Bounded Contexts Versus Subdomains

Subdomains

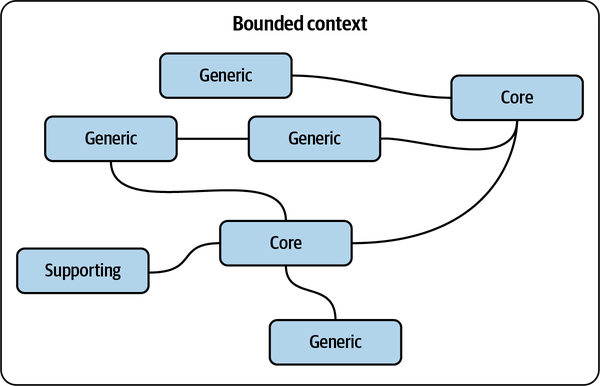

To comprehend a company’s business strategy, we have to analyze its business domain. According to domain-driven design methodology, the analysis phase involves identifying the different subdomains (core, supporting, and generic). That’s how the organization works and plans its competitive strategy.

Bounded Contexts

Bounded contexts, on the other hand, are designed. Choosing models’ boundaries is a strategic design decision. We decide how to divide the business domain into smaller, manageable problem domains.

The Interplay Between Subdomains and Bounded Contexts

Theoretically, though impractically, a single model could span the entire business domain.

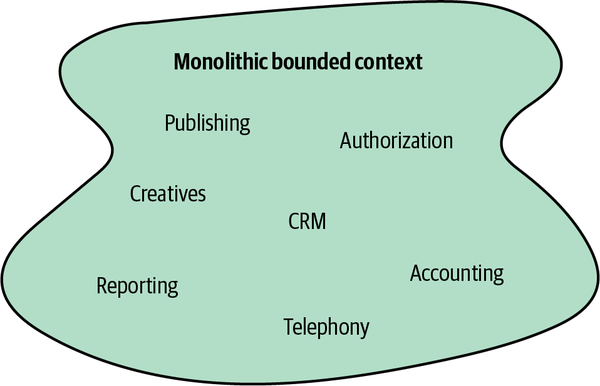

Figure 3-5. Monolithic bounded context

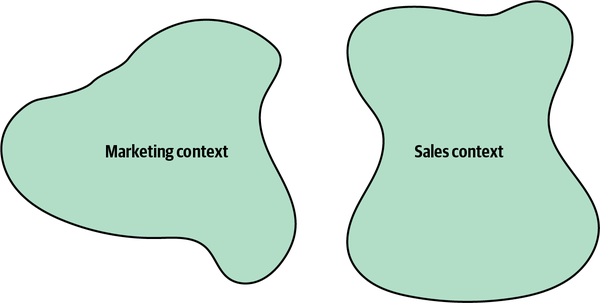

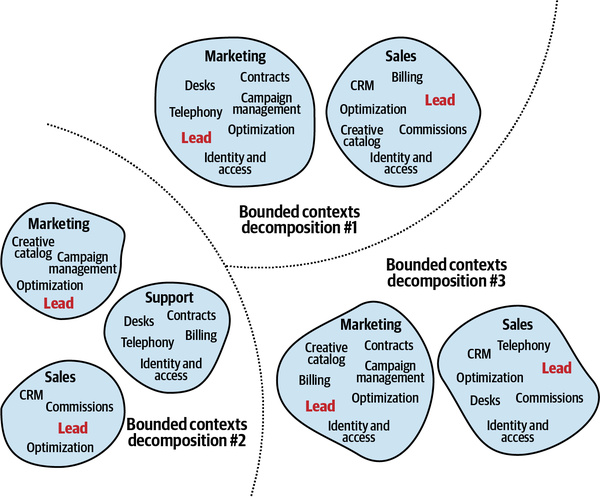

When conflicting models arise, we can follow the domain experts’ mental models and decompose the systems into bounded contexts, as shown in Figure 3-6.

Figure 3-6. Bounded contexts driven by the consistency of the ubiquitous language

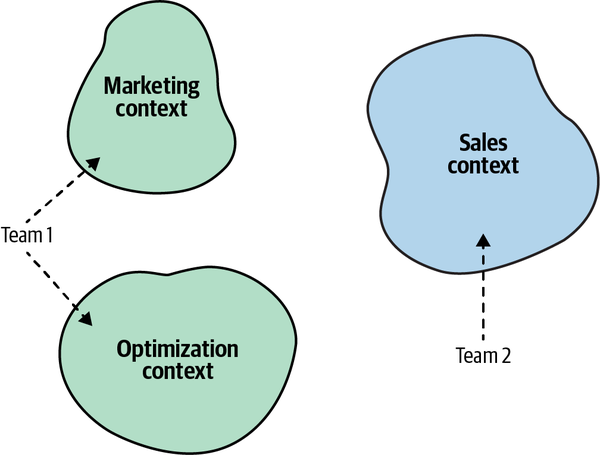

If the models are still large and hard to maintain, we can decompose them into even smaller bounded contexts; for example, by having a bounded context for each subdomain, as shown in Figure 3-7.

Figure 3-7. Bounded contexts aligned with subdomains’ boundaries

Either way, this is a design decision. We design those boundaries as a part of the solution.

Having a one-to-one relationship between bounded contexts and subdomains can be perfectly reasonable in some scenarios. In others, however, different decomposition strategies can be more suitable.

It’s crucial to remember that subdomains are discovered and bounded contexts are designed.1 The subdomains are defined by the business strategy. However, we can design the software solution and its bounded contexts to address the specific project’s context and constraints.

Finally, as you learned in Chapter 1, a model is intended to solve a specific problem. In some cases, it can be beneficial to use multiple models of the same concept simultaneously to solve different problems. As different types of maps provide different types of information about our planet, it may be reasonable to use different models of the same subdomain to solve different problems. Limiting the design to one-to-one relationships between bounded contexts would inhibit this flexibility and force us to use a single model of a subdomain in its bounded context.

Boundaries

Architectural design is system design. System design is contextual design—it is inherently about boundaries (what’s in, what’s out, what spans, what moves between), and about trade-offs. It reshapes what is outside, just as it shapes what is inside.2

The bounded context pattern is the domain-driven design tool for defining physical and ownership boundaries.

Physical Boundaries

Bounded contexts serve not only as model boundaries but also

Clear physical boundaries between bounded contexts allow us to implement each bounded context with the technology stack that best fits its needs.

Ownership Boundaries

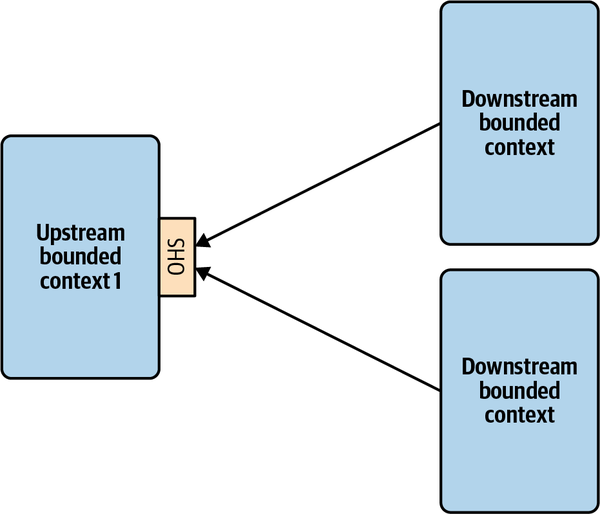

A bounded context should be implemented, evolved, and maintained by one team only. No two teams can work on the same bounded context. This segregation eliminates implicit assumptions that teams might make about one another’s models. Instead, they have to define communication protocols for integrating their models and systems explicitly.

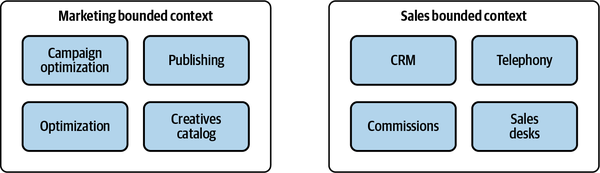

Figure 3-8. Team 1 working on the Marketing and Optimization bounded contexts, while Team 2 works on the Sales bounded context

Bounded Contexts in Real Life

In one of my domain driven-design classes, a participant once

Indeed, bounded contexts are not as evident as business domains and subdomains, but they are there, as domain experts’ mental models are. You just have to be conscious about how domain experts think about the different business entities and processes.

I want to close this chapter by discussing examples demonstrating that not only are bounded contexts there when we are modeling business domains in software, but the notion of using different models in different contexts is widespread in life in general.

Semantic Domains

A rather peculiar example of different semantic domains is the meaning of the word tomato.

According to the botanic definition, a fruit is the plant’s way of spreading its seeds. A fruit should grow from the plant’s flower, and bear at least one seed. A vegetable, on the other hand, is a general term encompassing all other edible parts of a plant: roots, stems, and leaves. Based on this definition, the tomato is a fruit.

That definition, however, is of little use in the context of the culinary arts. In this context, fruits and vegetables are defined based on their flavor profiles. A fruit has a soft texture, is either sweet or sour, and can be enjoyed in its raw form, whereas a vegetable has a tougher texture, tastes blander, and often requires cooking. According to this definition, the tomato is a vegetable.

Hence, in the bounded context of botany, the tomato is a fruit, while in the bounded context of the culinary arts, it’s a vegetable. But that’s not all.

In 1883 the United States established a 10% tax on imported vegetables, but not fruits. The botanic definition of the tomato as a fruit allowed the importation of tomatoes to the United States without paying the import tax. To close the loophole, in 1893 the United States Supreme Court made the decision to classify the tomato as a vegetable. Therefore, in the bounded context of taxation, the tomato is a vegetable.

Furthermore, as my friend Romeu Moura says, in the bounded context of theatrical performances, the tomato is a feedback mechanism.

Science

As historian Yuval Noah Harari puts it, “Scientists generally agree

This notion can be demonstrated by the different models of gravity introduced by Sir Isaac Newton and Albert Einstein. According to Newton’s laws of motion, space and time are absolute. They are the stage on which the motion of objects happens. In Einstein’s theory of relativity, space and time are no longer absolute but different for different observers.

Even though the two models can be seen as contradictory, both are useful in their suitable (bounded) contexts.

Buying a Refrigerator

Figure 3-9. A piece of cardboard

Is it just a piece of cardboard? No, it’s a model. It’s a model of the Siemens KG86NAI31L refrigerator. If you look it up, you may say the piece of cardboard doesn’t look anything like that fridge. It has no doors, and even its color is different.

Although that’s true, it’s not relevant. As we’ve discussed, a model is not supposed to copy a real-world entity. Instead, it should have a purpose—a problem it is supposed to solve. Hence, the correct question to ask about the cardboard is, what problem does this model solve?

In our apartment, we do not have a standard entry into the kitchen. The cardboard was cut precisely to the size of the fridge’s width and depth. The problem it solves is checking whether the refrigerator can fit through the kitchen door (see Figure 3-10).

Figure 3-10. The cardboard model in the kitchen doorway

Despite the cardboard not looking anything like the fridge, it proved extremely useful when we had to decide whether to buy this model or opt for a smaller one. Again, all models are wrong, but some are useful. Building a 3D model of the fridge would definitely be a fun project. But would it solve the problem any more efficiently than the cardboard? No. If the cardboard fits, the 3D model would fit as well, and vice versa. In software engineering terms, building a 3D model of the fridge would be gross overengineering.

But what about the refrigerator’s height? What if the base fits, but it’s too tall to fit in the doorway? Would that justify gluing together a 3D model of the fridge? No. The problem can be solved much more quickly and easily by using a simple tape measure to check the doorway’s height. What is a tape measure in this case? Another simple model.

So, we ended up with two models of the same fridge. Using two models, each optimized for its specific task, reflects the DDD approach to modeling business domains. Each model has its strict bounded context: the cardboard verifying that the refrigerator’s base can make it through the kitchen’s entry, and the tape measure verifying that it’s not too tall. A model should omit the extraneous information irrelevant to the task at hand. Also, there’s no need to design a complex jack-of-all-trades model if multiple, much simpler models can effectively solve each problem individually.

A few days after I published this story on Twitter, I received a reply saying that instead of fiddling with cardboard, I could have just used a mobile phone with a LiDAR scanner and an augmented reality (AR) application. Let’s analyze this suggestion from the domain-driven design perspective.

The author of the comment says this is a problem that others have already solved, and the solution is readily available. Needless to say, both the scanning technology and the AR application are complex. In DDD lingo, that makes the problem of checking whether the refrigerator will fit through the doorway a generic subdomain.

Conclusion

Whenever we stumble upon an inherent conflict in the domain experts’ mental models, we have to decompose the ubiquitous language into multiple bounded contexts. A ubiquitous language should be consistent within the scope of its bounded context. However, across bounded contexts, the same terms can have different meanings.

While subdomains are discovered, bounded contexts are designed. The division of the domain into bounded contexts is a strategic design decision.

A bounded context and its ubiquitous language can be implemented and maintained by one team. No two teams can share the work on the same bounded context. However, one team can work on multiple bounded contexts.

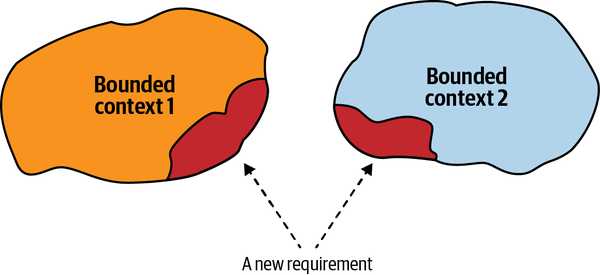

Bounded contexts decompose a system into physical components—services, subsystems, and so on. Each bounded context’s lifecycle is decoupled from the rest. Each bounded context can evolve independently from the rest of the system. However, the bounded contexts have to work together to form a system. Some of the changes will inadvertently affect another bounded context. In the next chapter, we’ll talk about the different patterns for integrating bounded contexts that can be used to protect them from cascading changes.

Exercises

-

What is the difference between subdomains and bounded contexts?

-

Subdomains are designed, while bounded contexts are discovered.

-

Bounded contexts are designed, while subdomains are discovered.

-

Bounded contexts and subdomains are essentially the same.

-

None of the above is true.

-

-

A bounded context is a boundary of:

-

A model

-

A lifecycle

-

Ownership

-

All of the above

-

-

Which of the following is true regarding the size of a bounded context?

The smaller the bounded context is, the more flexible the system is.

-

Bounded contexts should always be aligned with the boundaries of subdomains.

-

The wider the bounded context is, the better.

-

It depends.

-

-

Which of the following is true regarding team ownership of a bounded context?

-

Multiple teams can work on the same bounded context.

-

A single team can own multiple bounded contexts.

-

A bounded context can be owned by one team only.

-

B and C are correct.

-

-

Review the example of the WolfDesk company in the Preface and try to identify functionalities of the system that may require different models of a support ticket.

-