- Preface

- 1. What Happens When There Are No “Best Practices”?

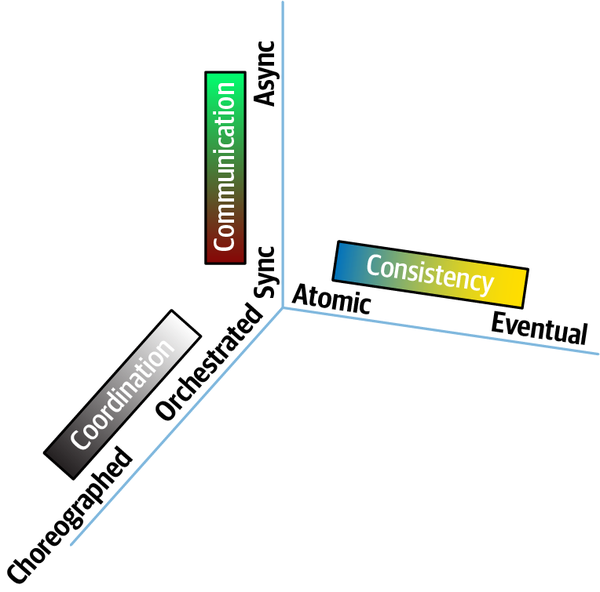

- I. Pulling Things Apart

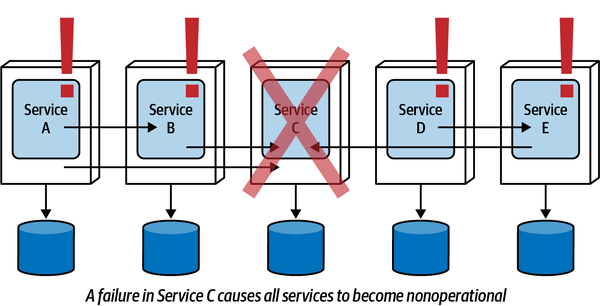

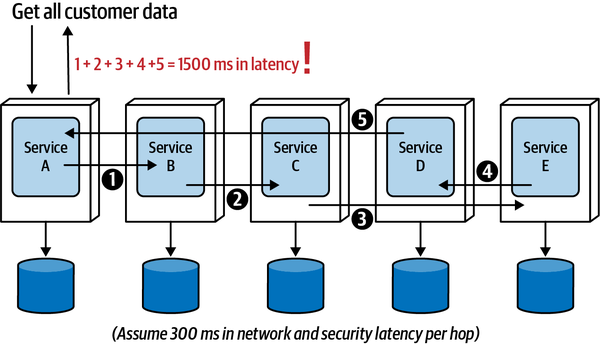

- 2. Discerning Coupling in Software Architecture

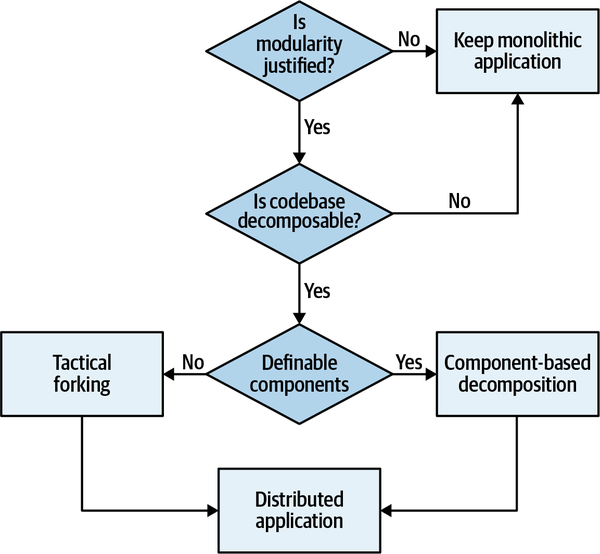

- 3. Architectural Modularity

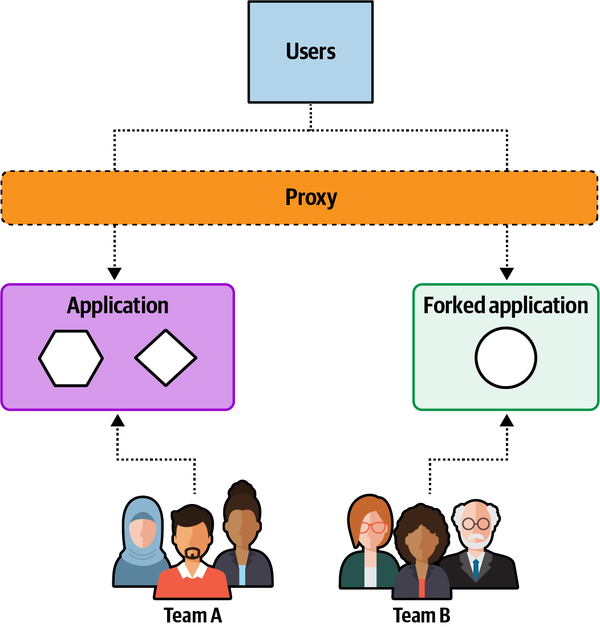

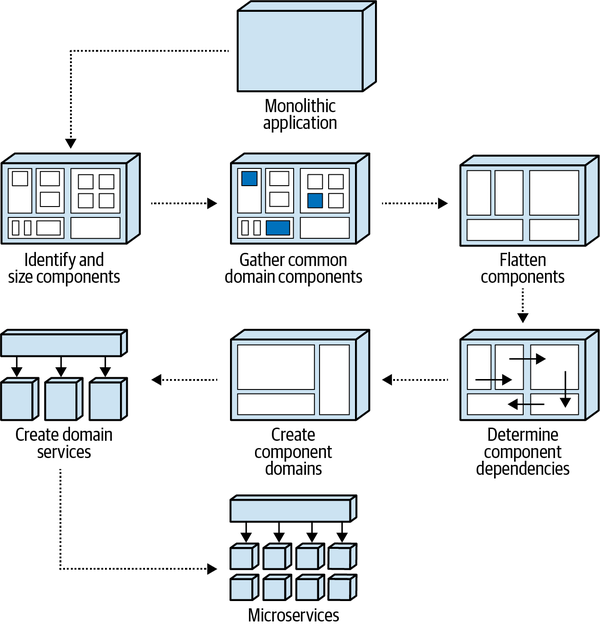

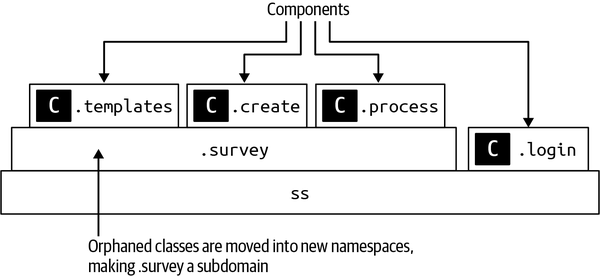

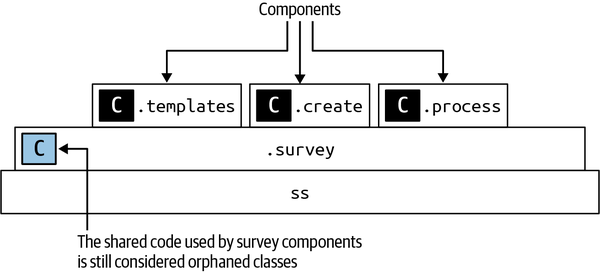

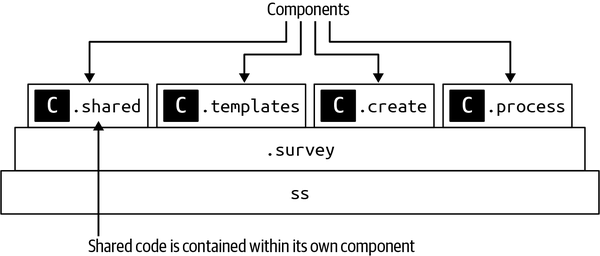

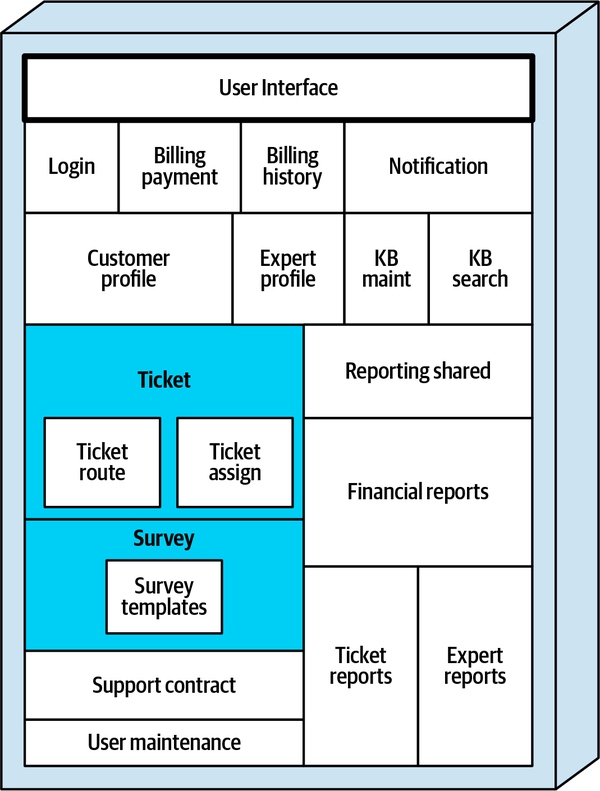

- 4. Architectural Decomposition

- 5. Component-Based Decomposition Patterns

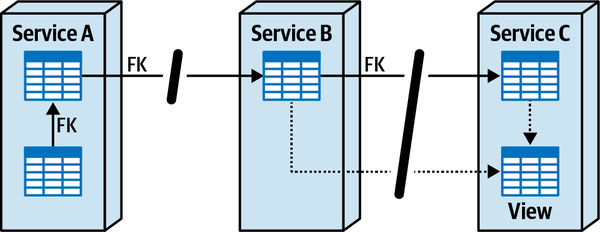

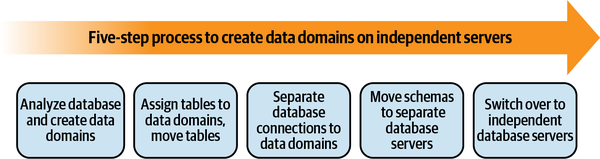

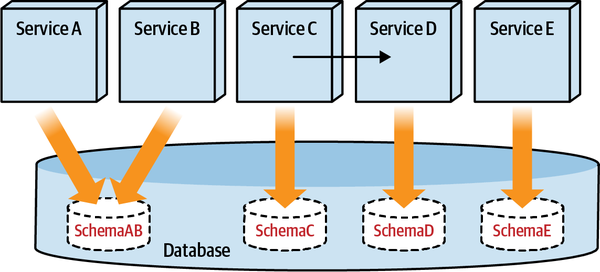

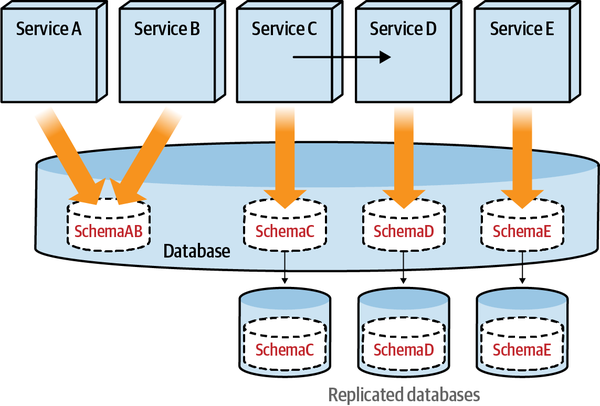

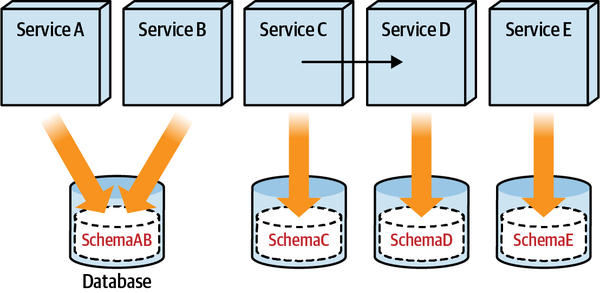

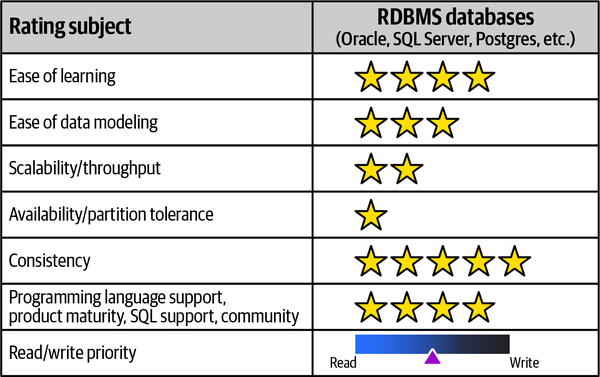

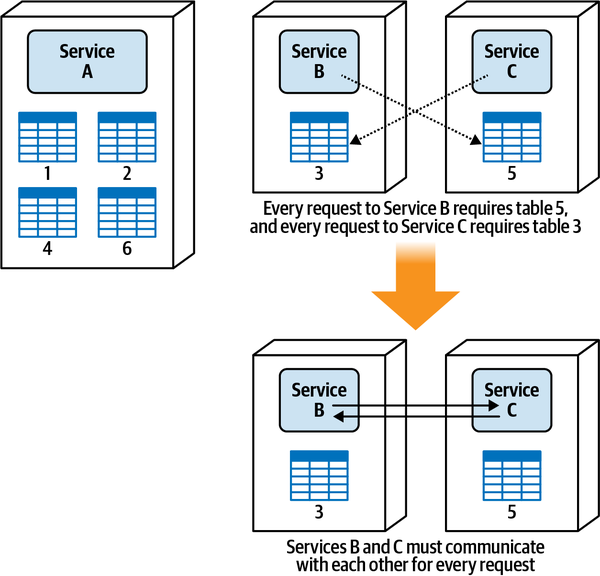

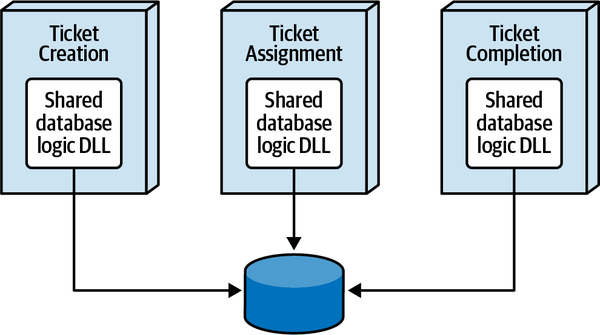

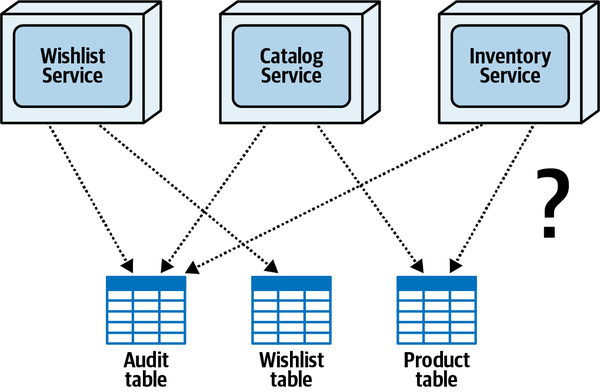

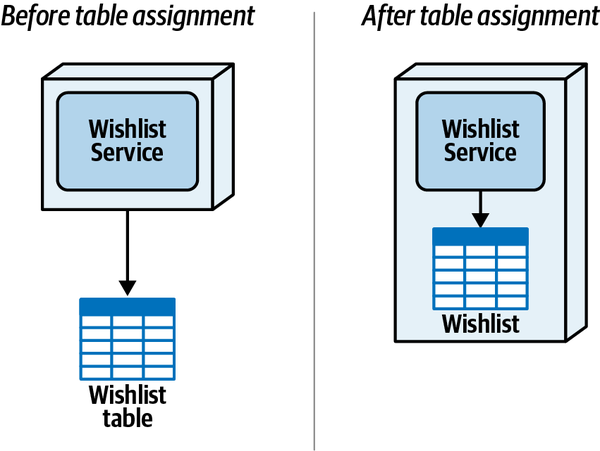

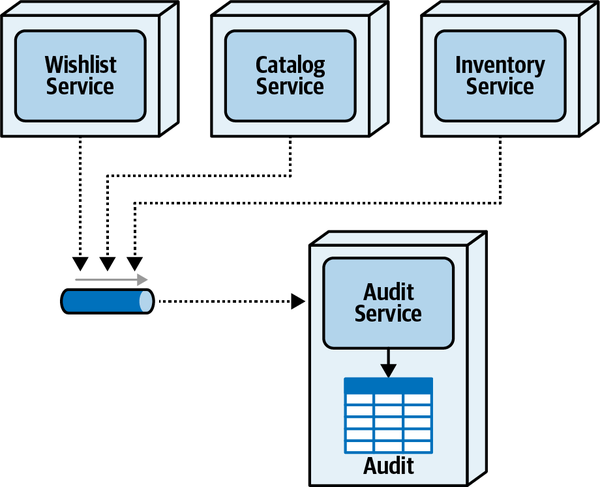

- 6. Pulling Apart Operational Data

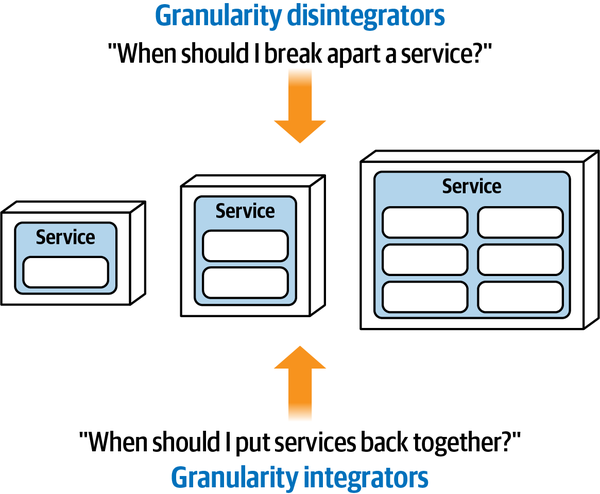

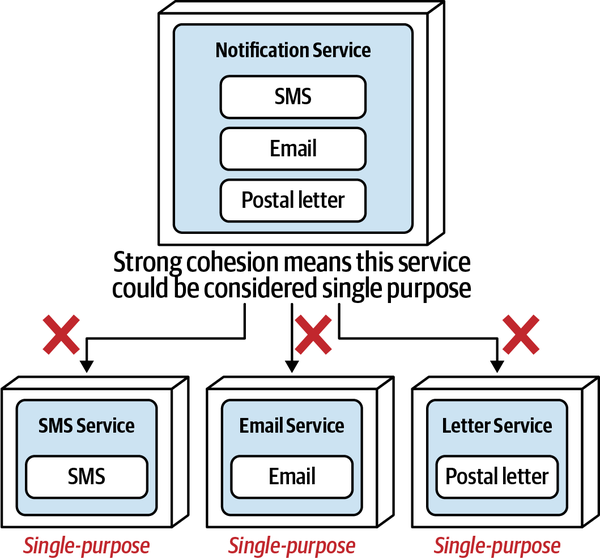

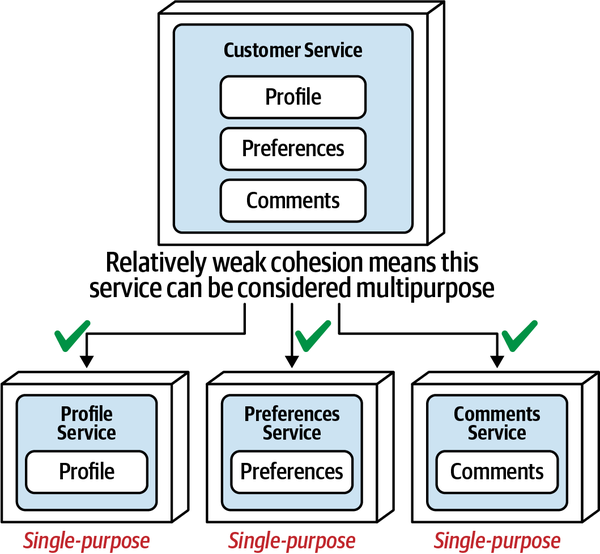

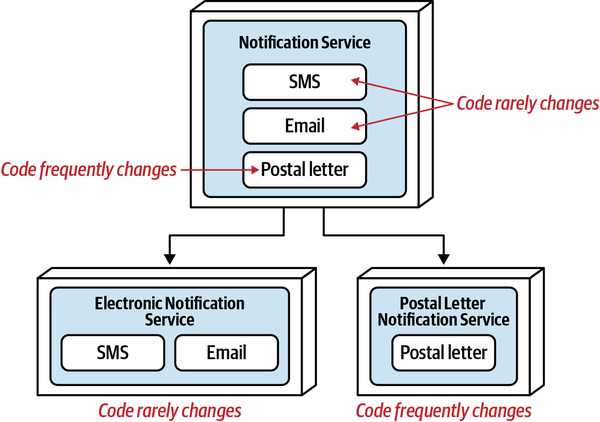

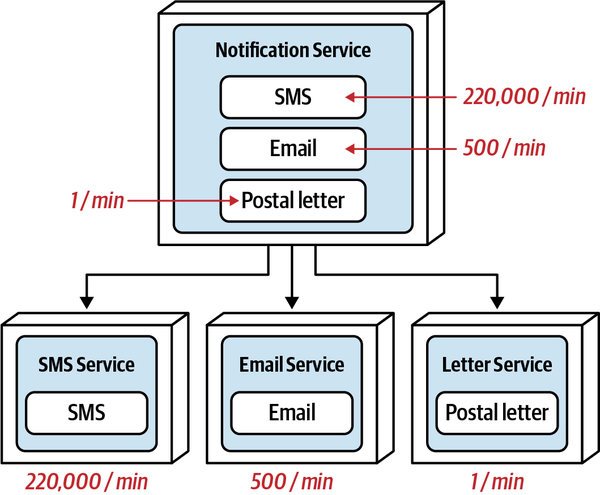

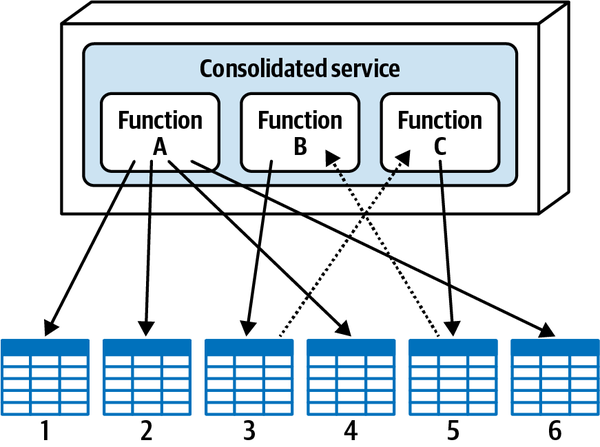

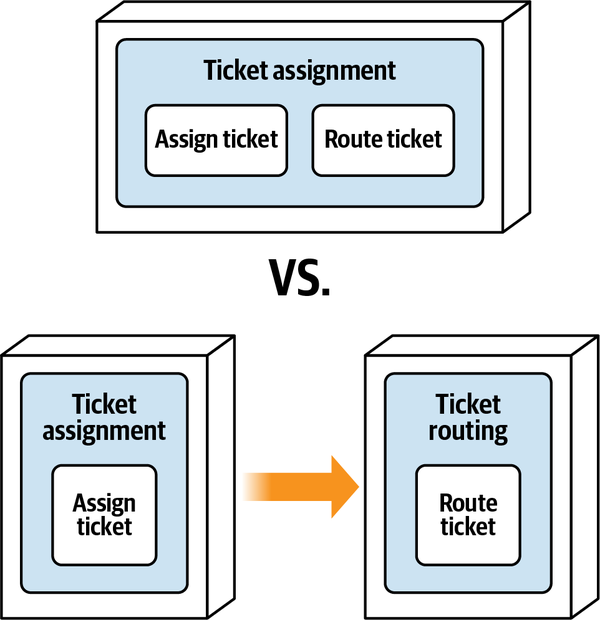

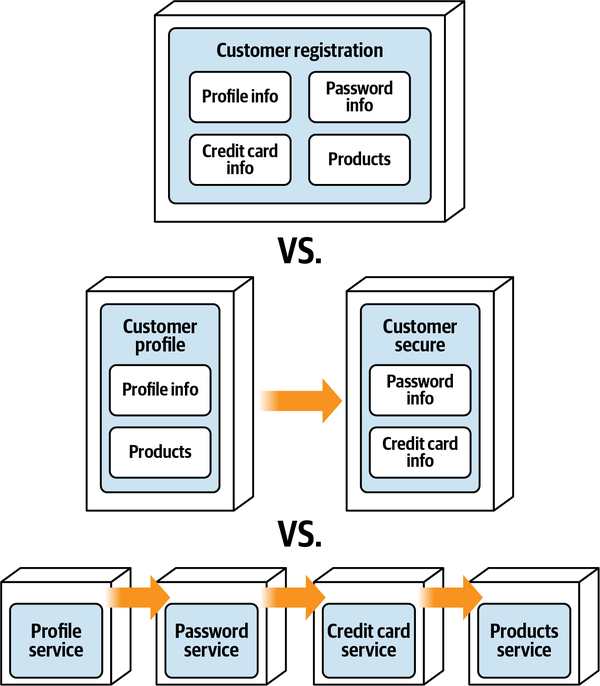

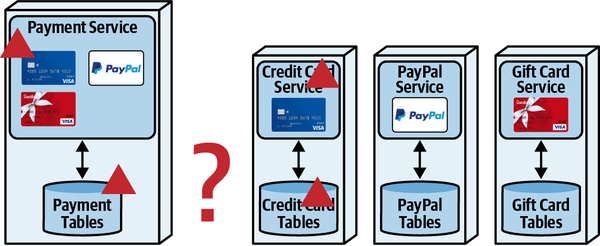

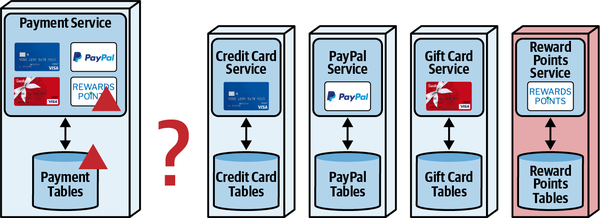

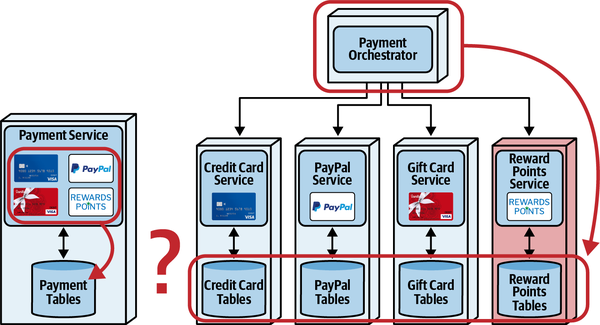

- 7. Service Granularity

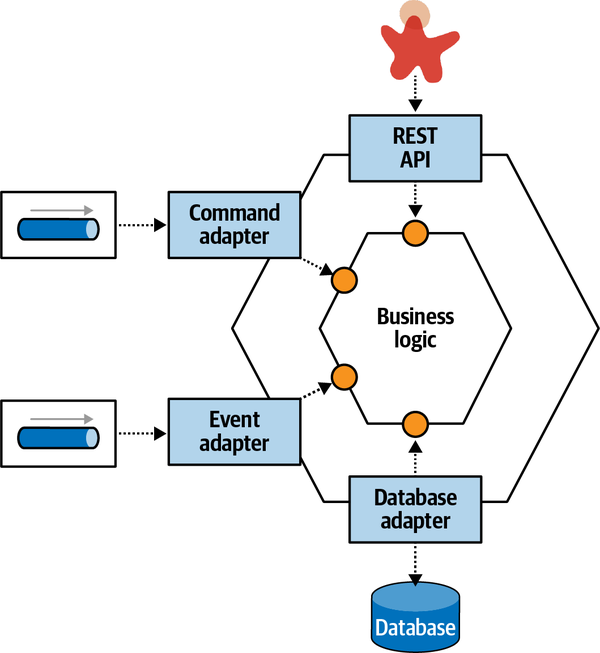

- II. Putting Things Back Together

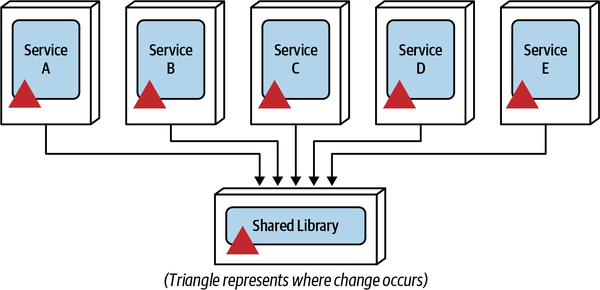

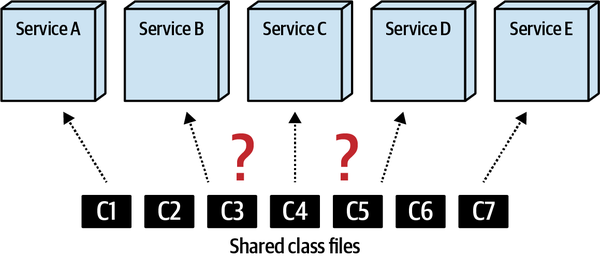

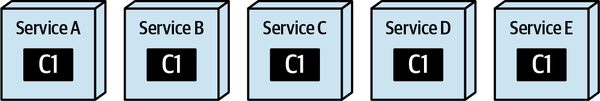

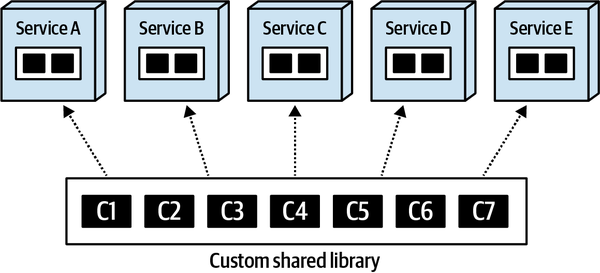

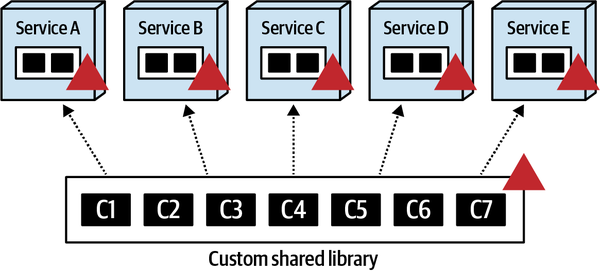

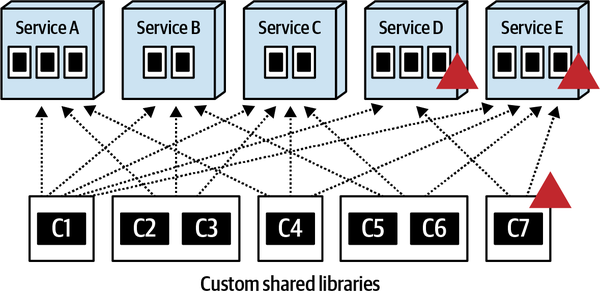

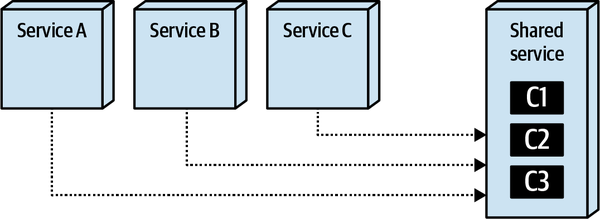

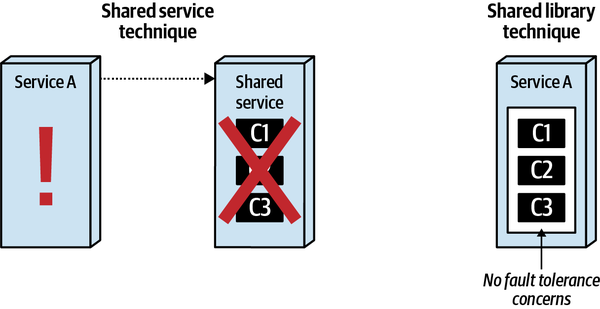

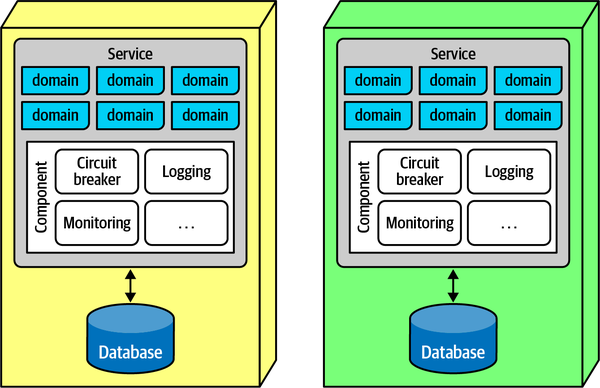

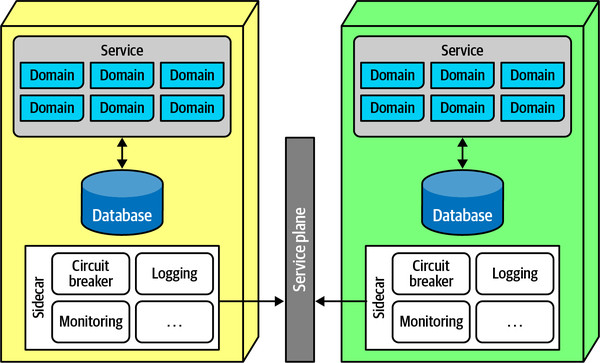

- 8. Reuse Patterns

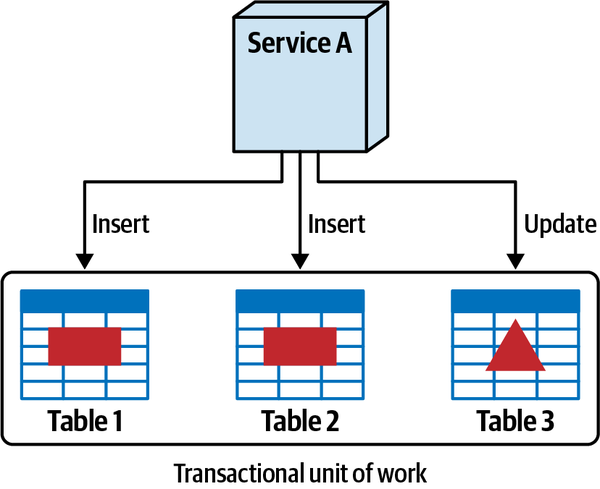

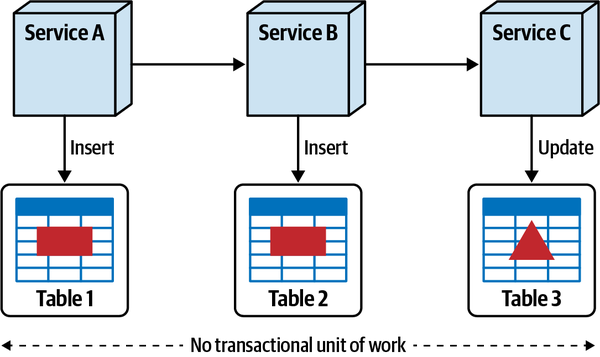

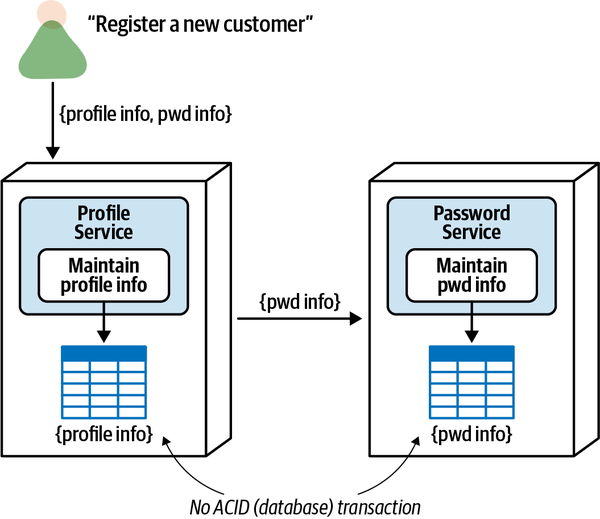

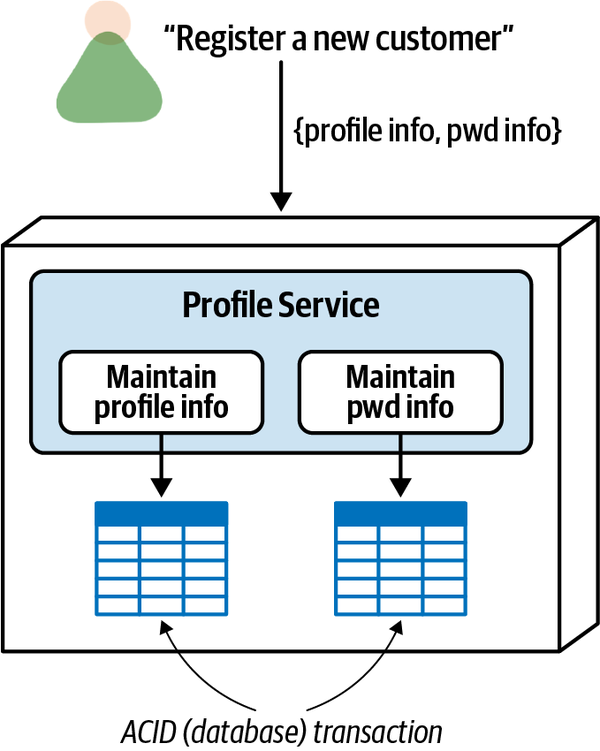

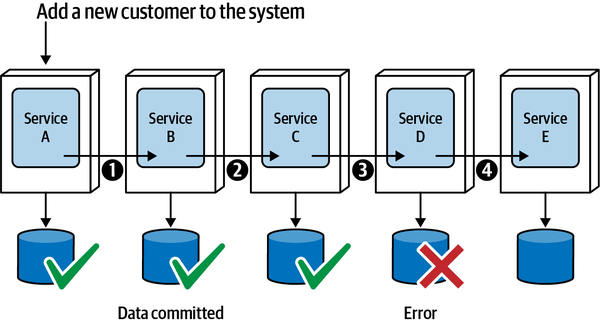

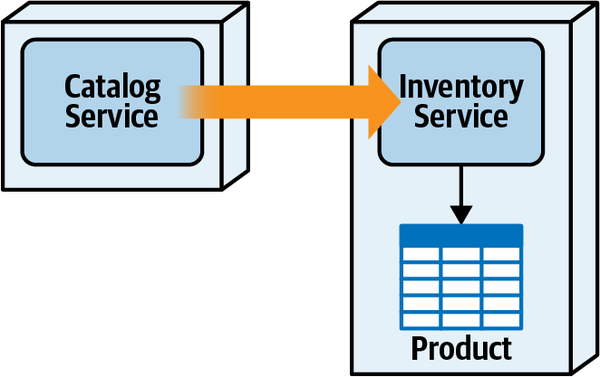

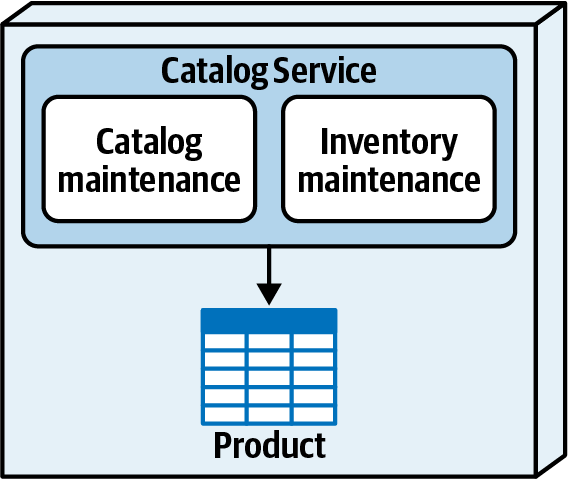

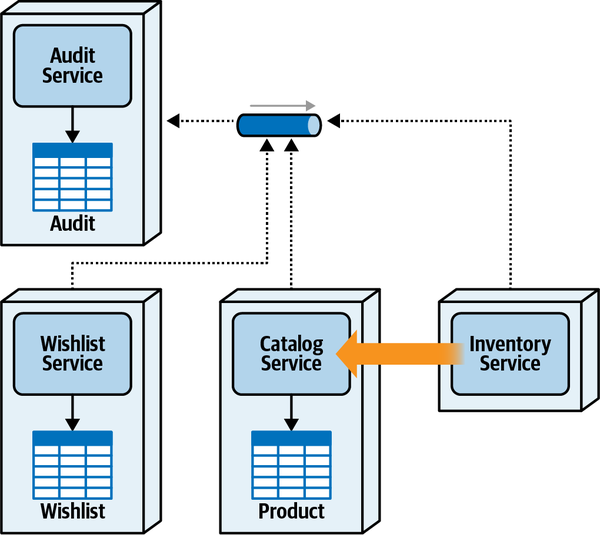

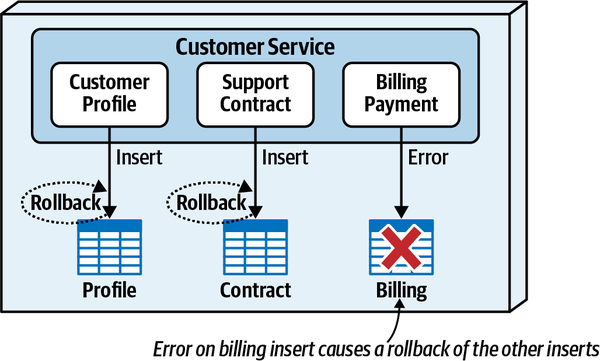

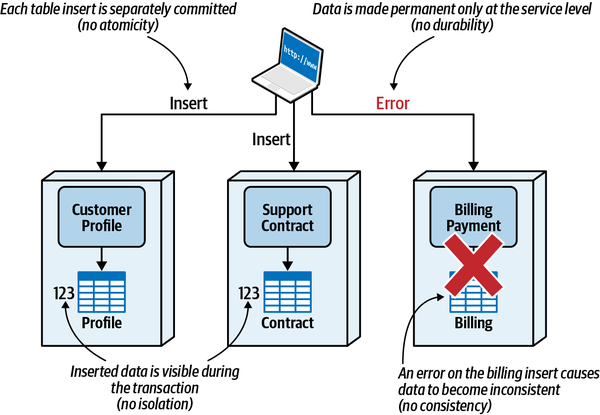

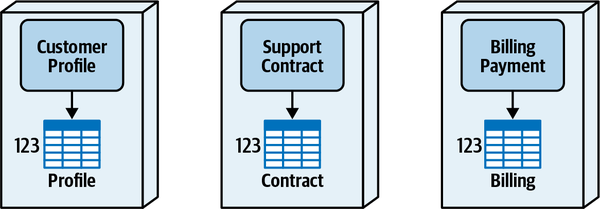

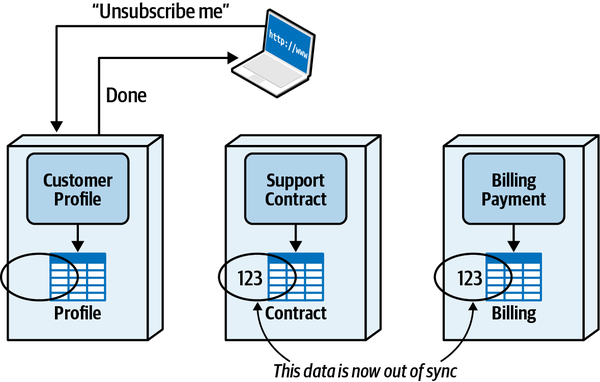

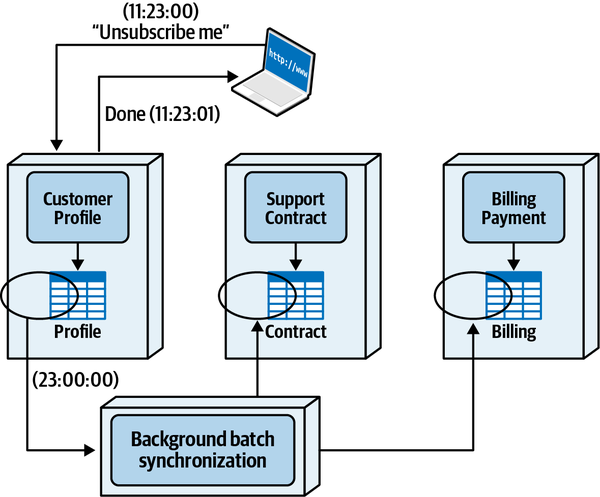

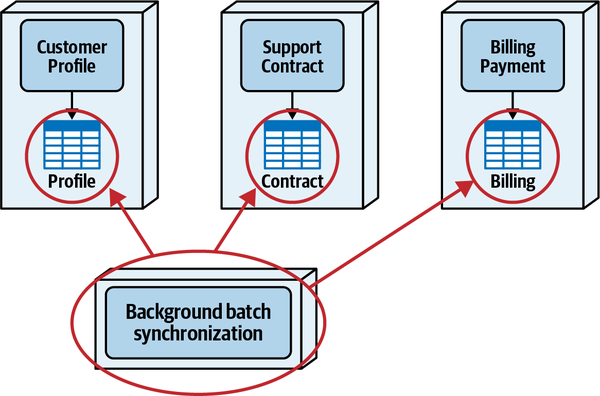

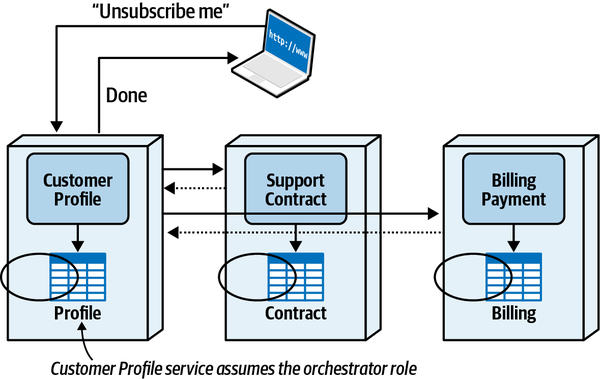

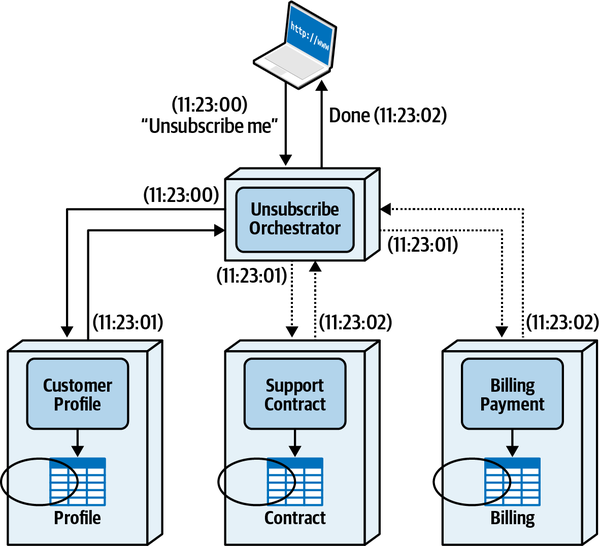

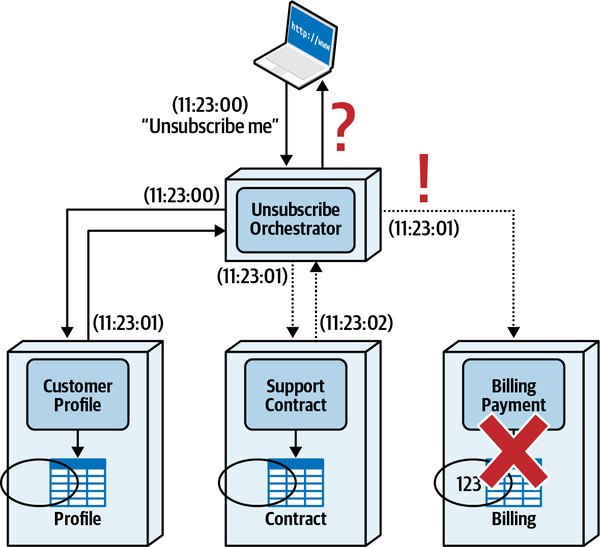

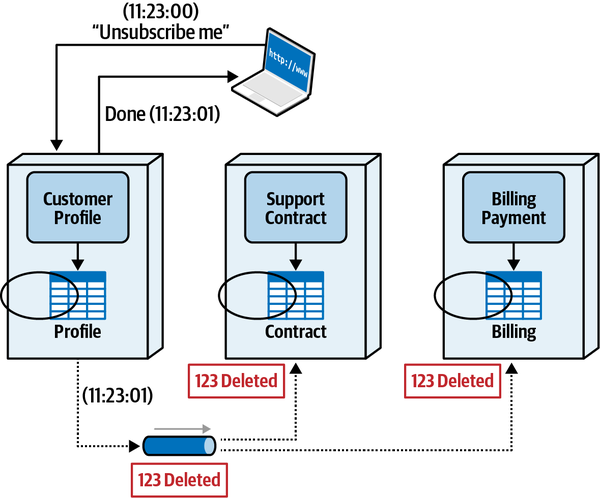

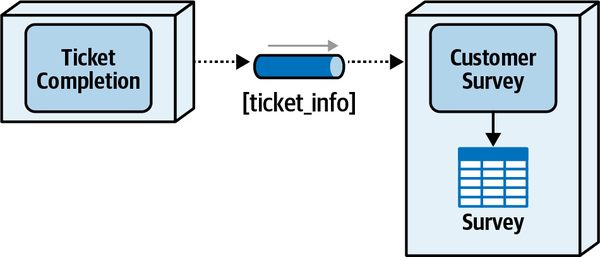

- 9. Data Ownership and Distributed Transactions

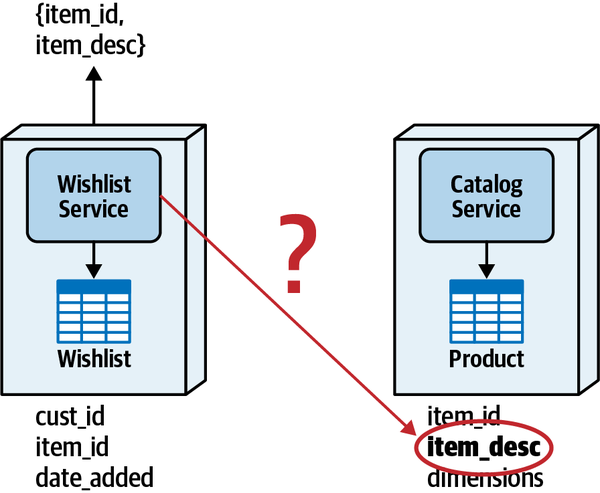

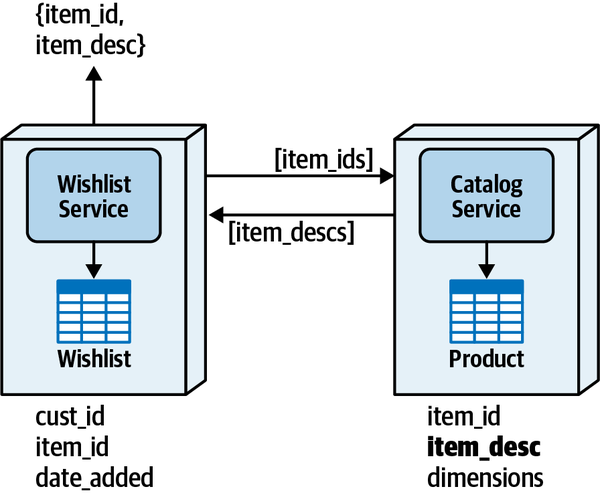

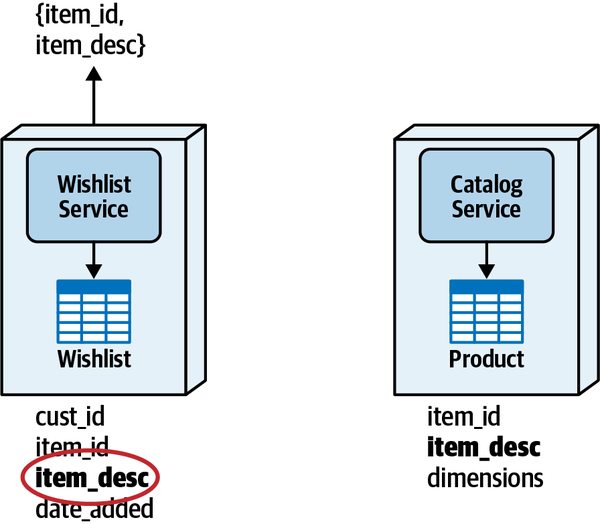

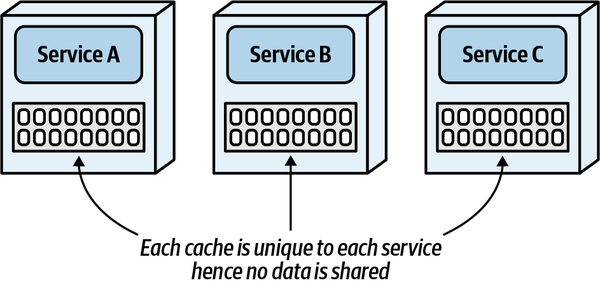

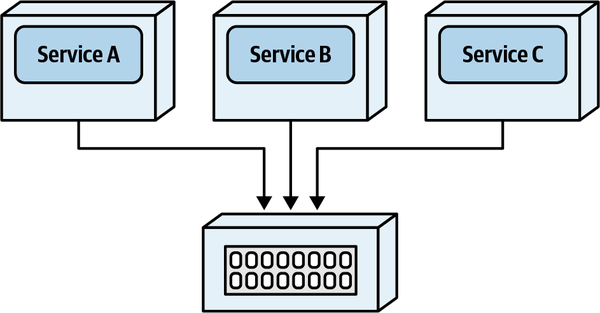

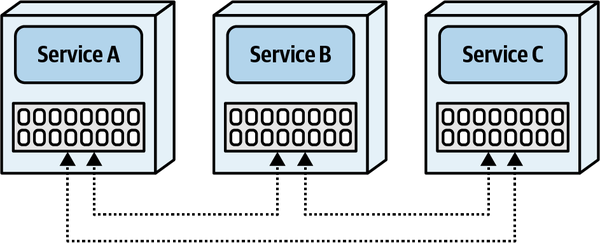

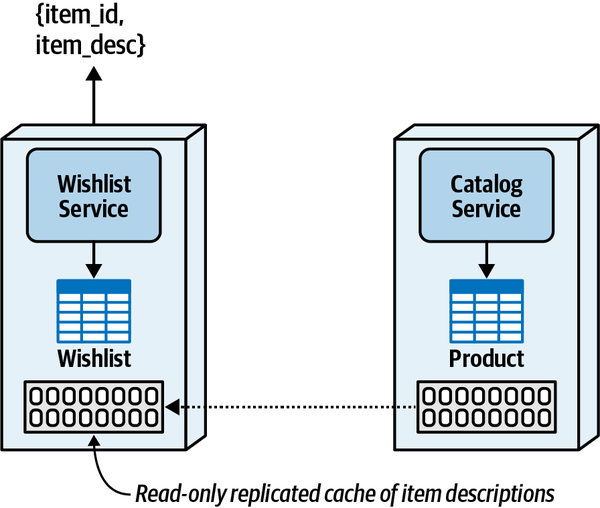

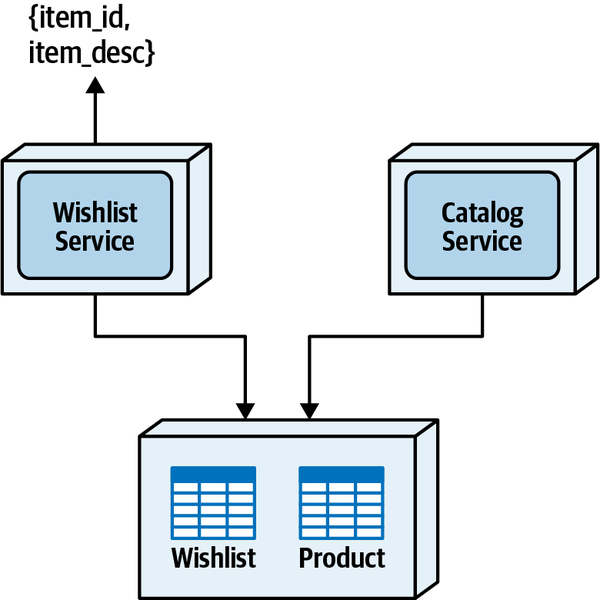

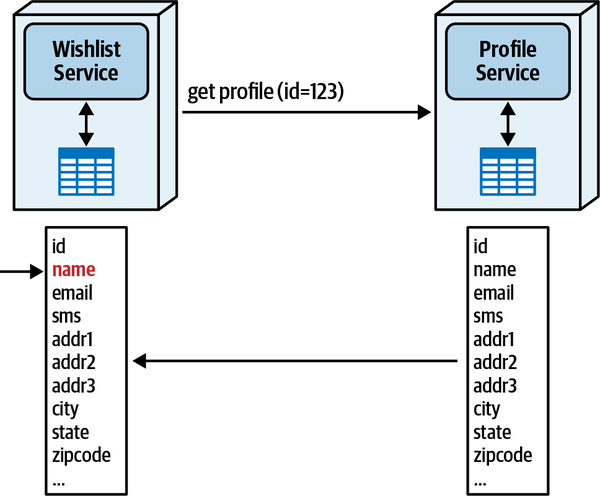

- 10. Distributed Data Access

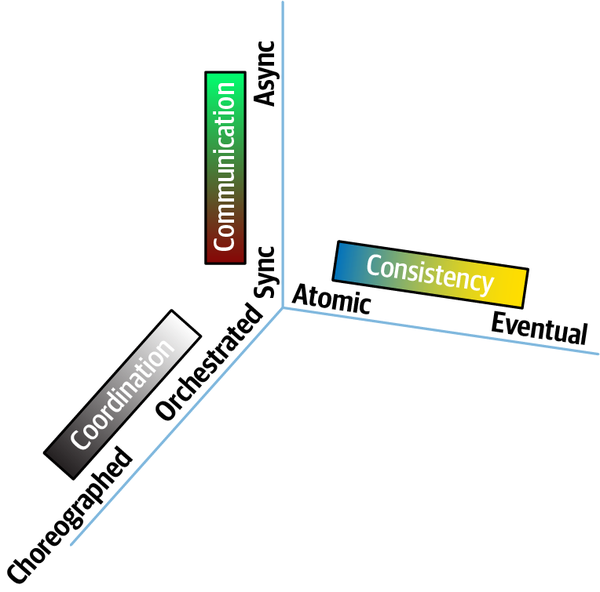

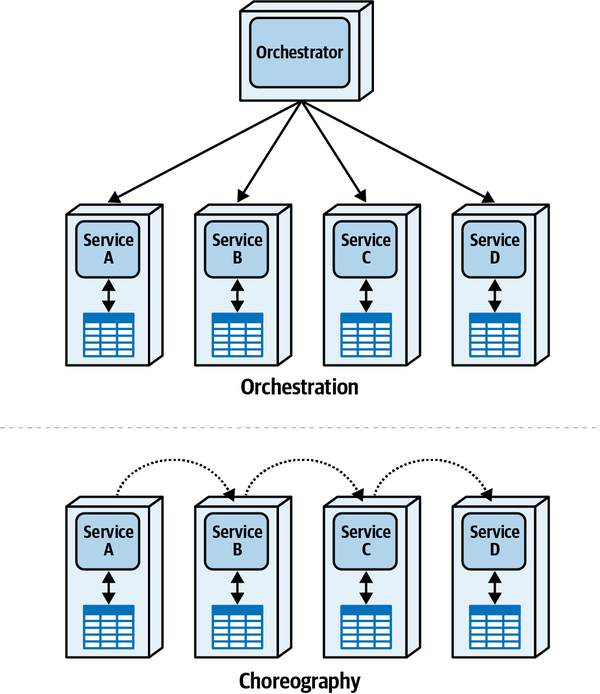

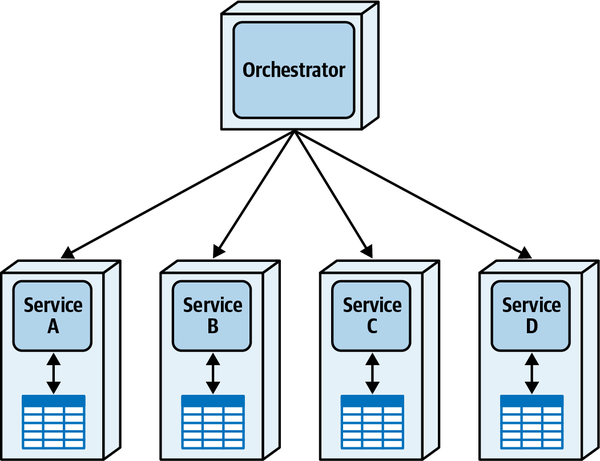

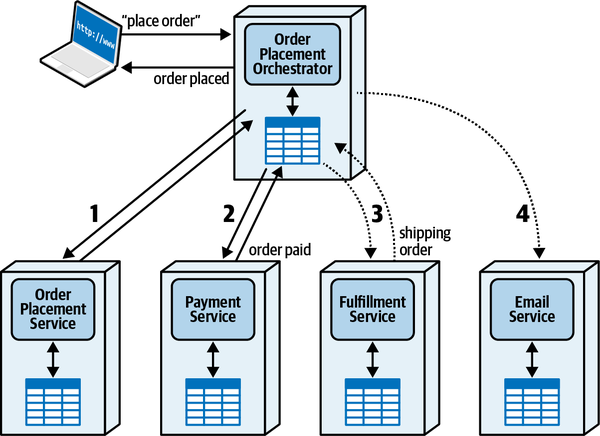

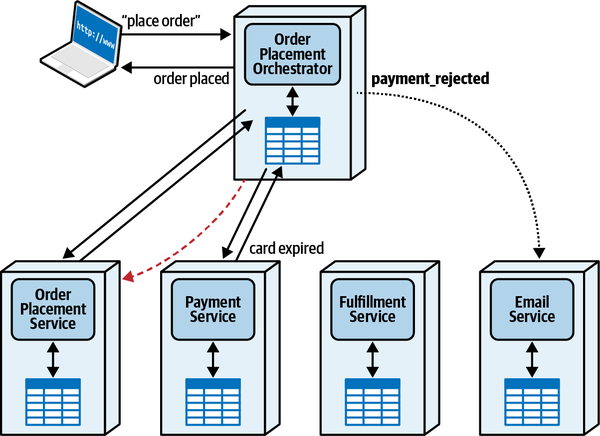

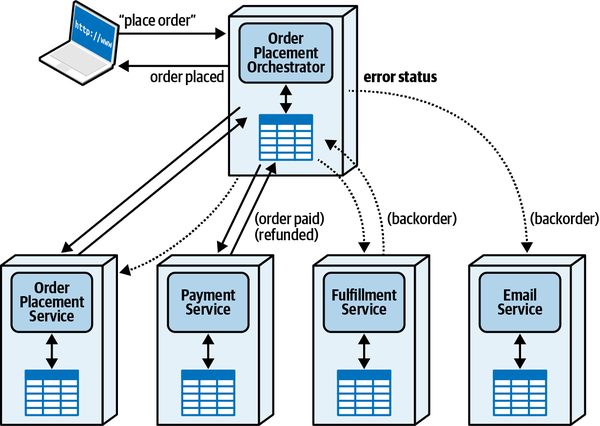

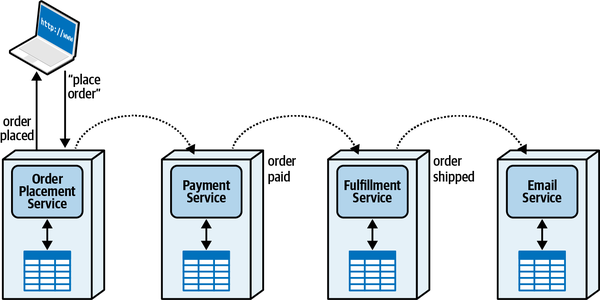

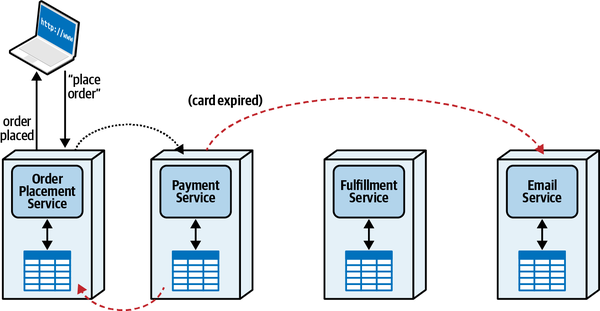

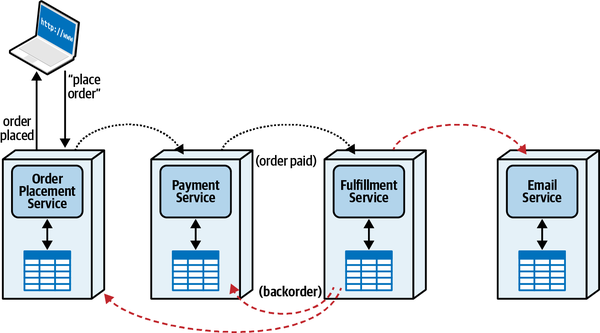

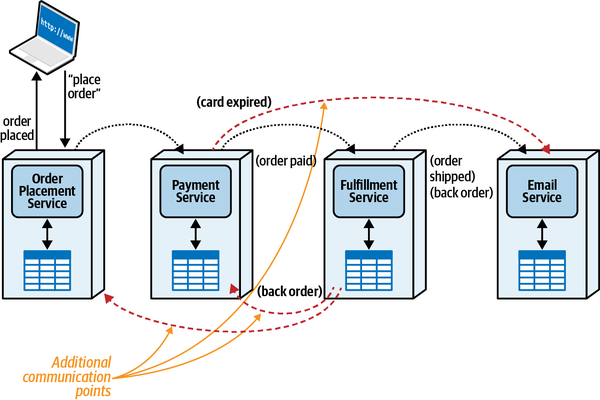

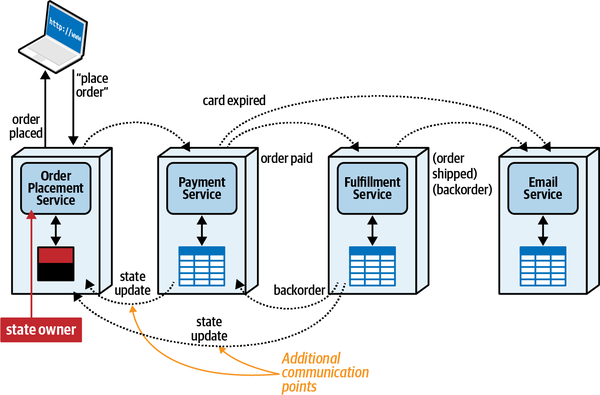

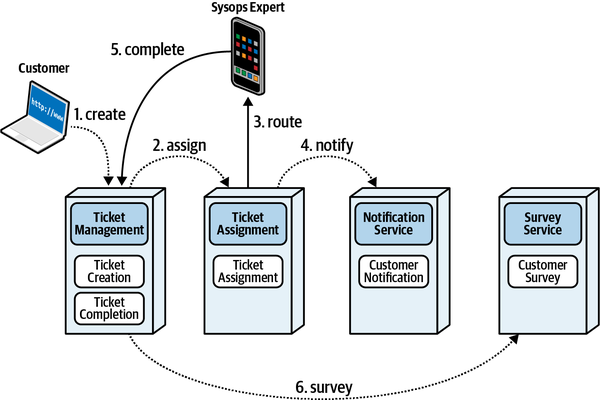

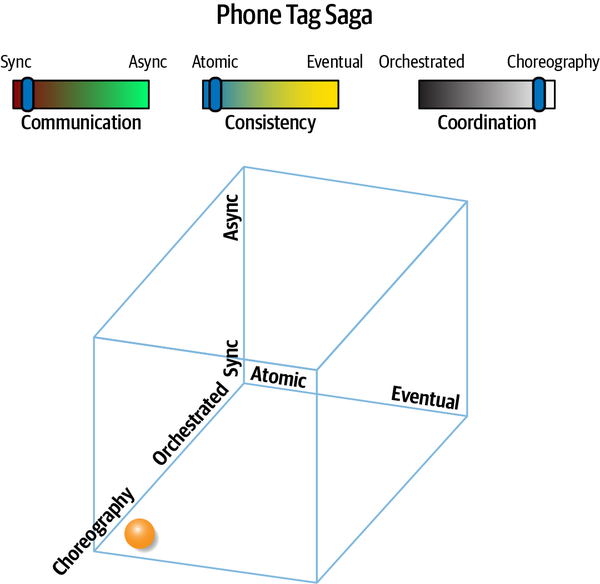

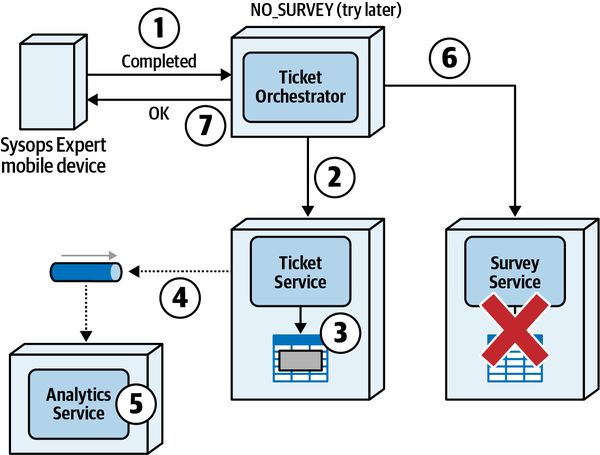

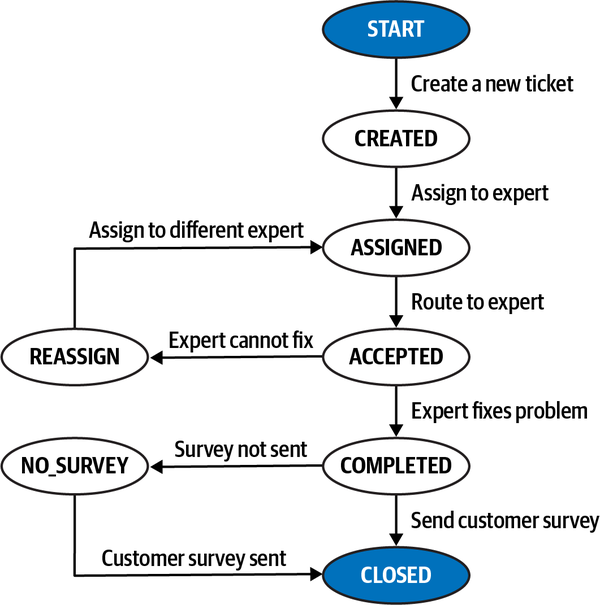

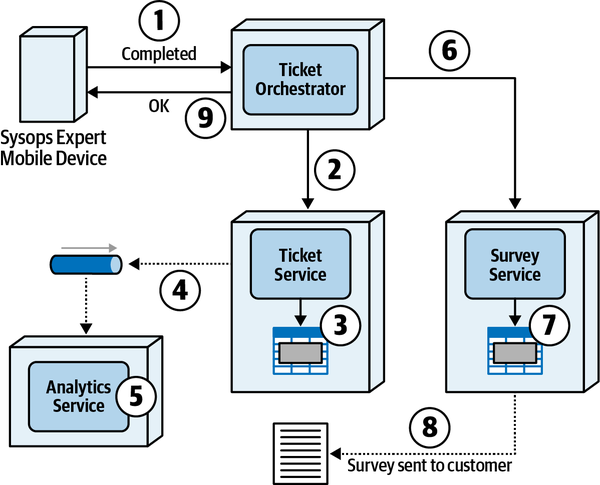

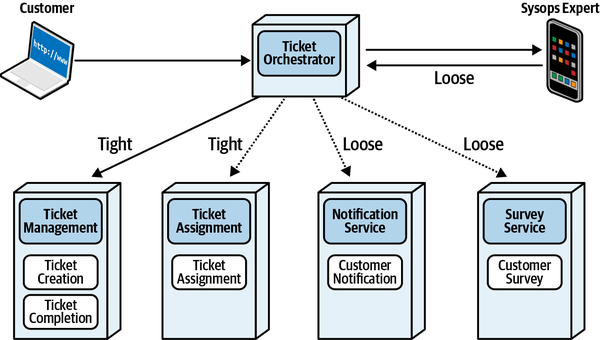

- 11. Managing Distributed Workflows

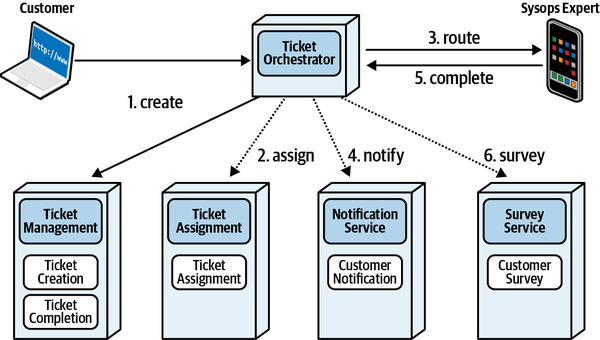

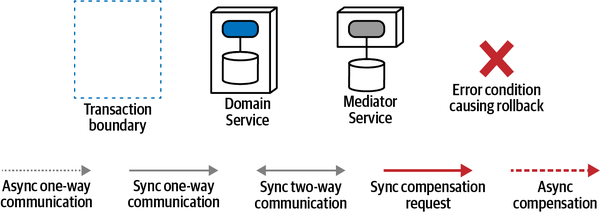

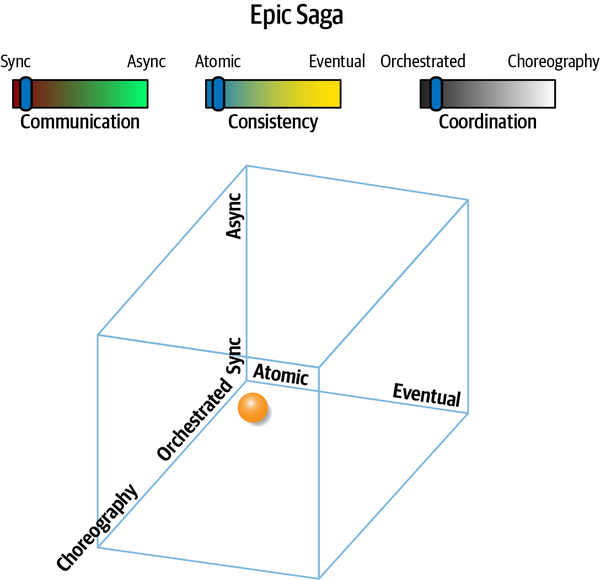

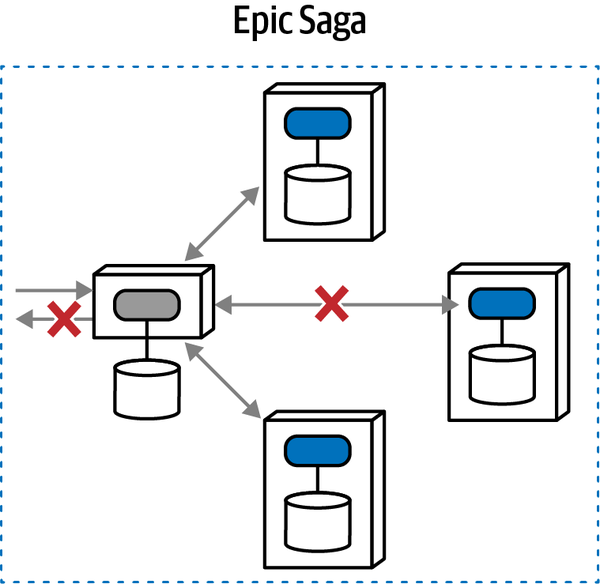

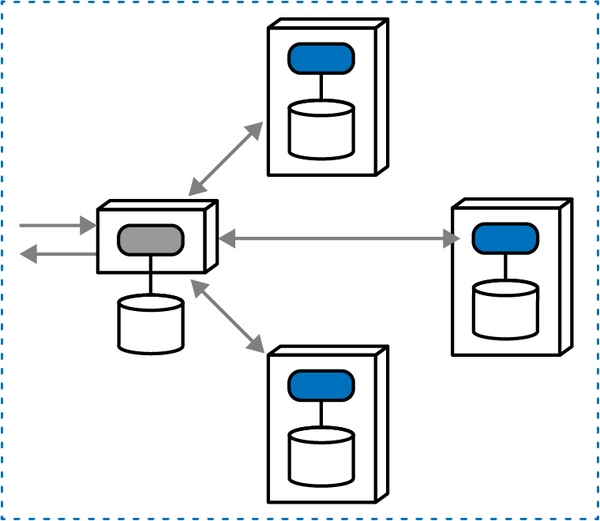

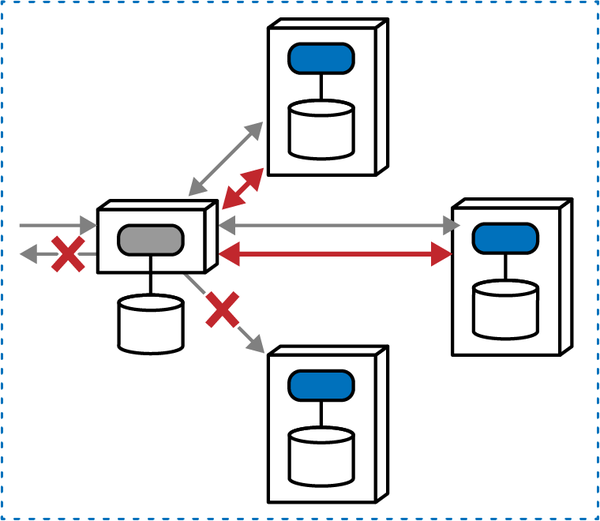

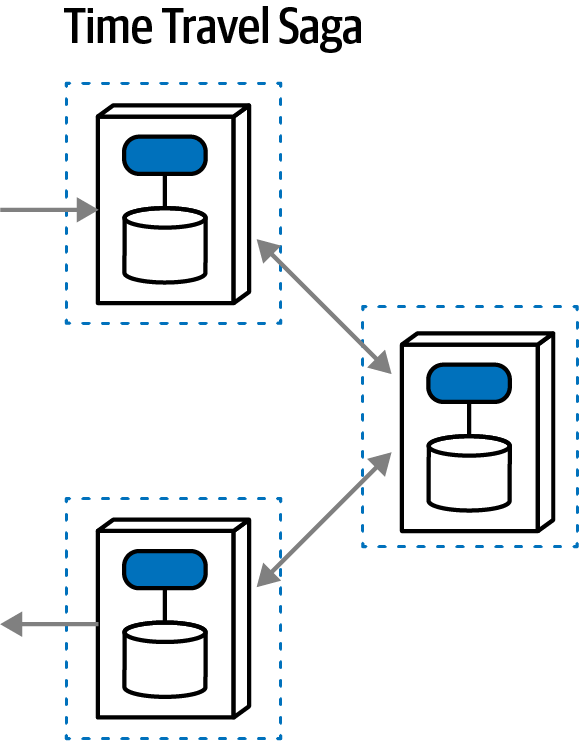

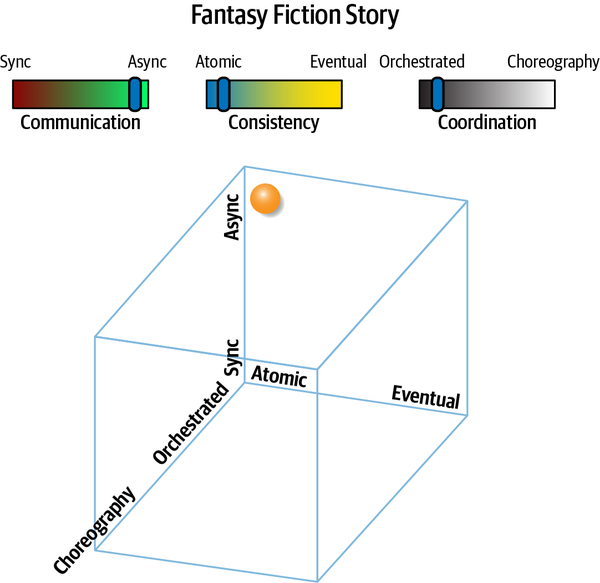

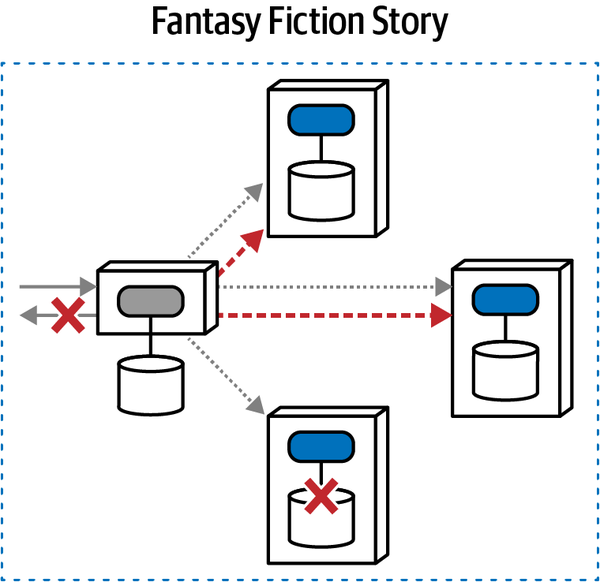

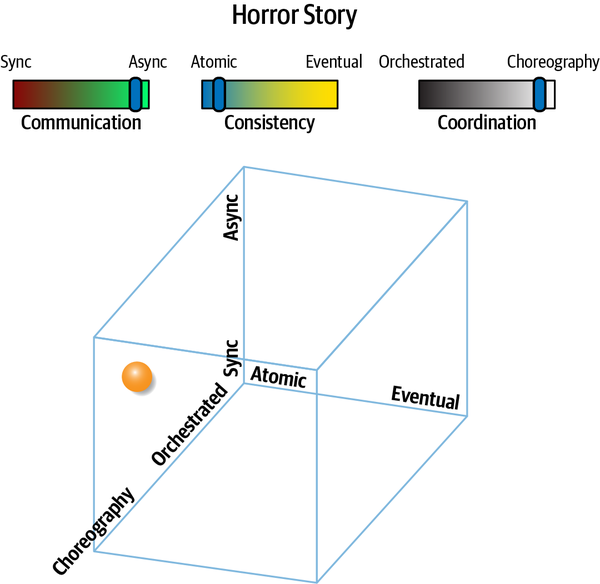

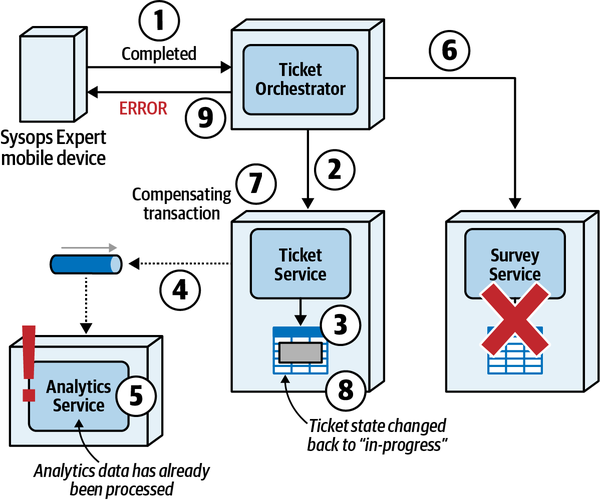

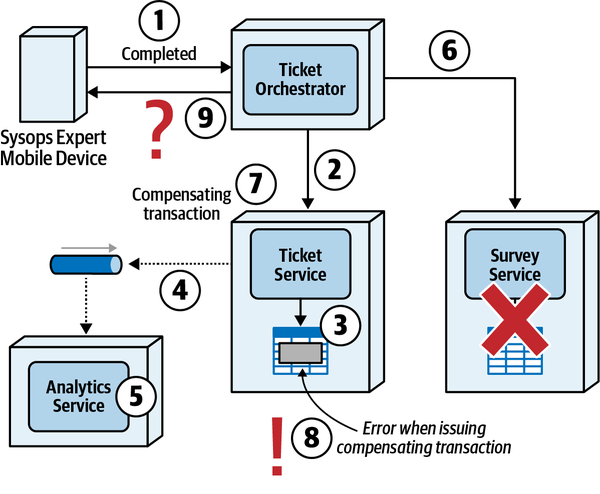

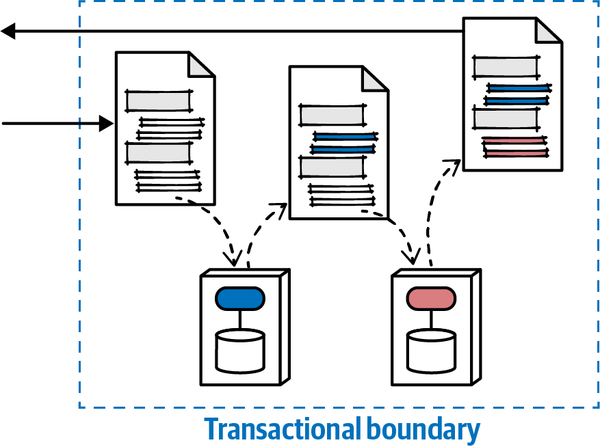

- 12. Transactional Sagas

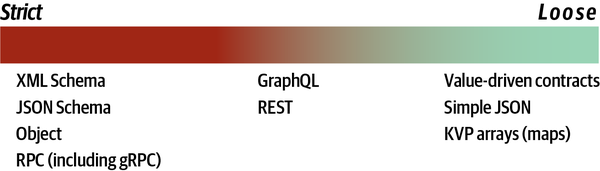

- 13. Contracts

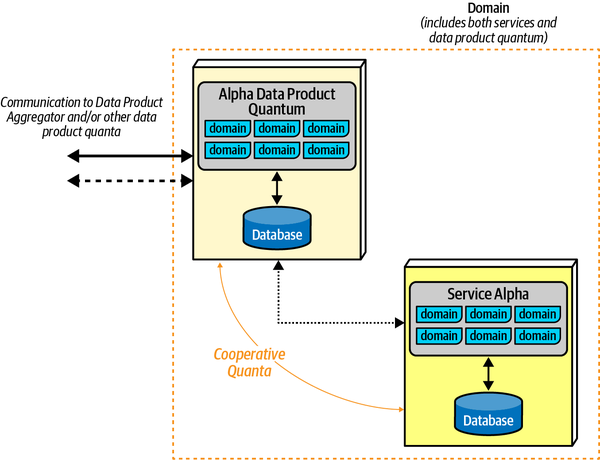

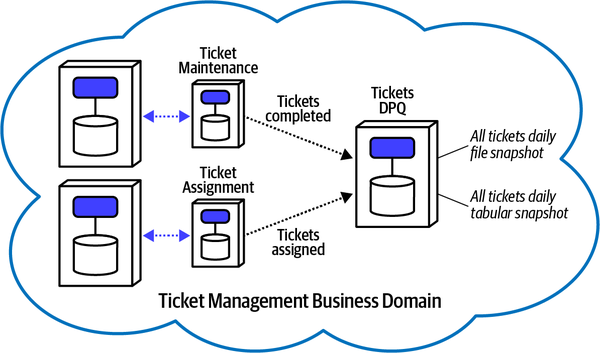

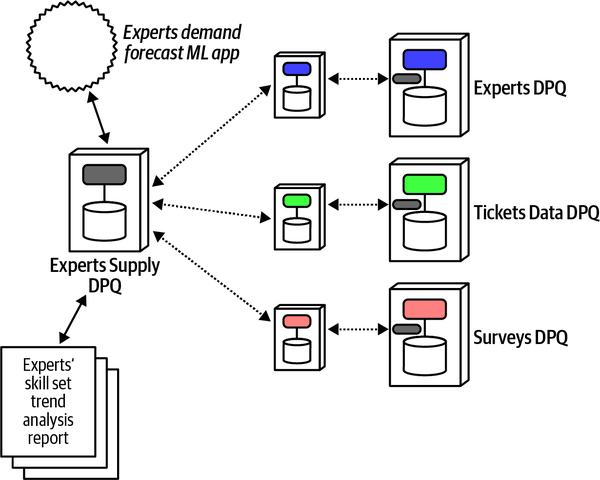

- 14. Managing Analytical Data

- 15. Build Your Own Trade-Off Analysis

- A. Concept and Term References

- B. Architecture Decision Record References

- C. Trade-Off References

- Index

Praise for Software Architecture: The Hard Parts

“This book provides the missing manual around building microservices and analyzing the nuances of architectural decisions throughout the whole tech stack. In this book, you get a catalog of architectural decisions you can make when building your distributed system and what are the pros and cons associated with each decision. This book is a must for every architect that is building modern distributed systems.”

Aleksandar Serafimoski, Lead Consultant, Thoughtworks

“It’s a must-read for technologists who are passionate about architecture. Great articulation of patterns.”

Vanya Seth, Head Of Tech, Thoughtworks India

“Whether you’re an aspiring architect or an experienced one leading a team, no handwaving, this book will guide you through the specifics of how to succeed in your journey to create enterprise applications and microservices.”

Dr. Venkat Subramaniam, Award-winning Author and Founder of Agile Developer, Inc.

“Software Architecture: The Hard Parts provides the reader with valuable insight, practices, and real-world examples on pulling apart highly coupled systems and building them back up again. By gaining effective trade-off analysis skills, you will start to make better architecture decisions.”

Joost van Wenen, Managing Partner & Cofounder, Infuze Consulting

“I loved reading this comprehensive body of work on distributed architectures! A great mix of solid discussions on fundamental concepts, together with tons of practical advice.”

David Kloet, Independent Software Architect

“Splitting a big ball of mud is no easy work. Starting from the code and getting to the data, this book will help you see the services that should be extracted and the services that should remain together.”

Rubén Díaz-Martínez, Software Developer at Codesai

“This book will equip you with the theoretical background and with a practical framework to help answer the most difficult questions faced in modern software architecture.”

James Lewis, Technical Director, Thoughtworks

Software Architecture: The Hard Parts

Modern Trade-Off Analysis for Distributed Architectures

Neal Ford, Mark Richards, Pramod Sadalage, and Zhamak Dehghani

Software Architecture: The Hard Parts

by Neal Ford, Mark Richards, Pramod Sadalage, and Zhamak Dehghani

Copyright © 2022 Neal Ford, Mark Richards, Pramod Sadalage, and Zhamak Dehghani. All rights reserved.

Printed in Canada.

Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472.

O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (http://oreilly.com). For more information, contact our corporate/institutional sales department: 800-998-9938 or corporate@oreilly.com.

- Acquisitions Editor: Melissa Duffield

- Development Editor: Nicole Taché

- Production Editor: Christopher Faucher

- Copyeditor: Sonia Saruba

- Proofreader: Sharon Wilkey

- Indexer: Sue Klefstad

- Interior Designer: David Futato

- Cover Designer: Karen Montgomery

- Illustrator: O’Reilly Media, Inc.

- October 2021: First Edition

Revision History for the First Edition

- 2021-09-23: First Release

See http://oreilly.com/catalog/errata.csp?isbn=9781492086895 for release details.

The O’Reilly logo is a registered trademark of O’Reilly Media, Inc. Software Architecture: The Hard Parts, the cover image, and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc.

The views expressed in this work are those of the authors, and do not represent the publisher’s views. While the publisher and the authors have used good faith efforts to ensure that the information and instructions contained in this work are accurate, the publisher and the authors disclaim all responsibility for errors or omissions, including without limitation responsibility for damages resulting from the use of or reliance on this work. Use of the information and instructions contained in this work is at your own risk. If any code samples or other technology this work contains or describes is subject to open source licenses or the intellectual property rights of others, it is your responsibility to ensure that your use thereof complies with such licenses and/or rights.

978-1-492-08689-5

[MBP]

Preface

When two of your authors, Neal and Mark, were writing the book Fundamentals of Software Architecture, we

We took all the examples and worked through them like architects, applying trade-off analysis for each situation, but also paying attention to the process we used to arrive at the trade-offs. One of our early revelations was the increasing importance of data in architecture decisions: who can/should access data, who can/should write to it, and how to manage the separation of analytical and operational data. To that end, we asked experts in those fields to join us, which allows this book to fully incorporate decision making from both angles: architecture to data and data to architecture.

The result is this book: a collection of difficult problems in modern software architecture, the trade-offs that make the decisions hard, and ultimately an illustrated guide to show you how to apply the same trade-off analysis to your own unique problems.

Conventions Used in This Book

The following typographical conventions are used in this book:

- Italic

-

Indicates new terms, URLs, email addresses, filenames, and file paths.

Constant width-

Used for program listings, as well as within paragraphs to refer to program elements such as variable or function names, databases, data types, environment variables, statements, and keywords.

Constant width bold-

Shows commands or other text that should be typed literally by the user.

Constant width italic-

Shows text that should be replaced with user-supplied values or by values determined by context.

Tip

This element signifies a tip or suggestion.

Using Code Examples

This book is here to help you get your job done. In general, if example code is offered with this book, you may use it in your programs and documentation. You do not need to contact us for permission unless you’re reproducing a significant portion of the code. For example, writing a program that uses several chunks of code from this book does not require permission. Selling or distributing examples from O’Reilly books does require permission. Answering a question by citing this book and quoting example code does not require permission. Incorporating a significant amount of example code from this book into your product’s documentation does require permission.

We appreciate, but generally do not require, attribution. An attribution usually includes the title, author, publisher, and ISBN. For example: “Software Architecture: The Hard Parts by Neal Ford, Mark Richards, Pramod Sadalage, and Zhamak Dehghani (O’Reilly). Copyright 2022 Neal Ford, Mark Richards, Pramod Sadalage, and Zhamak Dehghani, 978-1-492-08689-5.”

If you feel your use of code examples falls outside fair use or the permission given above, feel free to contact us at permissions@oreilly.com.

O’Reilly Online Learning

Note

For more than 40 years, O’Reilly Media has provided technology and business training, knowledge, and insight to help companies succeed.

Our unique network of experts and innovators share their knowledge and expertise through books, articles, and our online learning platform. O’Reilly’s online learning platform gives you on-demand access to live training courses, in-depth learning paths, interactive coding environments, and a vast collection of text and video from O’Reilly and 200+ other publishers. For more information, visit http://oreilly.com.

How to Contact Us

Please address comments and questions concerning this book to the publisher:

- O’Reilly Media, Inc.

- 1005 Gravenstein Highway North

- Sebastopol, CA 95472

- 800-998-9938 (in the United States or Canada)

- 707-829-0515 (international or local)

- 707-829-0104 (fax)

We have a web page for this book, where we list errata, examples, and any additional information. You can access this page at https://oreil.ly/sa-the-hard-parts.

Email bookquestions@oreilly.com to comment or ask technical questions about this book.

For news and information about our books and courses, visit http://oreilly.com.

Find us on Facebook: http://facebook.com/oreilly

Follow us on Twitter: http://twitter.com/oreillymedia

Watch us on YouTube: http://youtube.com/oreillymedia

Acknowledgments

Mark and Neal would like to thank all the people who attended our (almost exclusively online) classes, workshops, conference sessions, and user group meetings, as well as all the other people who listened to versions of this material and provided invaluable feedback. Iterating on new material is especially tough when we can’t do it live, so we appreciate those who commented on the many iterations. We thank the publishing team at O’Reilly, who made this as painless an experience as writing a book can be. We also thank a few random oases of sanity-preserving and idea-sparking groups that have names like Pasty Geeks and the Hacker B&B.

Thanks to those who did the technical review of our book—Vanya Seth, Venkat Subramanian, Joost van Weenen, Grady Booch, Ruben Diaz, David Kloet, Matt Stein, Danilo Sato, James Lewis, and Sam Newman. Your valuable insights and feedback helped validate our technical content and make this a better book.

We especially want to acknowledge the many workers and families impacted by the unexpected global pandemic. As knowledge workers, we faced inconveniences that pale in comparison to the massive disruption and devastation wrought on so many of our friends and colleagues across all walks of life. Our sympathies and appreciation especially go out to health care workers, many of whom never expected to be on the front line of a terrible global tragedy yet handled it nobly. Our collective thanks can never be adequately expressed.

Acknowledgments from Mark Richards

In addition to the preceding acknowledgments, I once again thank my lovely wife, Rebecca, for putting up with me through yet another book project. Your unending support and advice helped make this book happen, even when it meant taking time away from working on your own novel. You mean the world to me, Rebecca. I also thank my good friend and coauthor Neal Ford. Collaborating with you on the materials for this book (as well as our last one) was truly a valuable and rewarding experience. You are, and always will be, my friend.

Acknowledgments from Neal Ford

I would like to thank my extended family, Thoughtworks as a collective, and Rebecca Parsons and Martin Fowler as individual parts of it. Thoughtworks is an extraordinary group of people who manage to produce value for customers while keeping a keen eye toward why things work so that we can improve them. Thoughtworks supported this book in many ways and continues to grow Thoughtworkers who challenge and inspire me every day. I also thank our neighborhood cocktail club for a regular escape from routine, including the weekly outside, socially distanced versions that helped us all survive the odd time we just lived through. I thank my long-time friend Norman Zapien, who never ceases to provide enjoyable conversation. Lastly, I thank my wife, Candy, who continues to support this lifestyle that has me staring at things like book writing rather than our cats too much.

Acknowledgments from Pramod Sadalage

I thank my wife, Rupali, for all the support and understanding, and my lovely girls, Arula and Arhana, for the encouragement; daddy loves you both. All the work I do would not be possible without the clients I work with and various conferences that have helped me iterate on the concepts and content. I thank AvidXchange, the latest client I am working with, for its support and providing great space to iterate on new concepts. I also thank Thoughtworks for its continued support in my life, and Neal Ford, Rebecca Parsons, and Martin Fowler for being amazing mentors; you all make me a better person. Lastly, thank you to my parents, especially my mother, Shobha, whom I miss every day. I miss you, MOM.

Acknowledgments from Zhamak Dehghani

I thank Mark and Neal for their open invitation to contribute to this amazing body of work. My contribution to this book would not have been possible without the continuous support of my husband, Adrian, and patience of my daughter, Arianna. I love you both.

Chapter 1. What Happens When There Are No “Best Practices”?

Why does a technologist like a software architect present at a conference or write a book? Because they have discovered what is colloquially known as a “best practice,”

But what happens for that vast set of problems that have no good solutions? Entire classes of problems exist in software architecture that have no general good solutions, but rather present one messy set of trade-offs cast against an (almost) equally messy set.

Software developers build outstanding skills in searching online for solutions to a current problem. For example, if they need to figure out how to configure a particular tool in their environment, expert use of Google finds the answer.

But that’s not true for architects.

For architects, many problems present unique challenges because they conflate the exact environment and circumstances of your organization—what are the chances that someone has encountered exactly this scenario and blogged it or posted it on Stack Overflow?

Architects may have wondered why so few books exist about architecture compared to technical topics like frameworks, APIs, and so on. Architects rarely experience common problems but constantly struggle with decision making in novel situations. For architects, every problem is a snowflake. In many cases, the problem is novel not just within a particular organization but rather throughout the world. No books or conference sessions exist for those problems!

There is no single development, in either technology or management technique, which by itself promises even one order of magnitude [tenfold] improvement within a decade in productivity, in reliability, in simplicity.

Fred Brooks from “No Silver Bullet”

Tip

Don’t try to find the best design in software architecture; instead, strive for the least worst combination of trade-offs.

Often, the best design an architect can create is the least worst collection of trade-offs—no single architecture characteristics excels as it would alone, but the balance of all the competing architecture characteristics promote project success.

Which begs the question: “How can an architect find the least worst combination of trade-offs (and document them effectively)?” This book is primarily about decision making, enabling architects to make better decisions when confronted with novel situations.

Why “The Hard Parts”?

Second, hard connotes solidity—just as in the separation of hardware and software, the hard one should change much less because it provides the foundation for the soft stuff. Similarly, architects discuss the distinction between architecture and design, where the former is structural and the latter is more easily changed. Thus, in this book, we talk about the foundational parts of architecture.

Giving Timeless Advice About Software Architecture

When architects look at a particular style (especially a historical one), they must consider the constraints in place that lead to that architecture becoming dominant. At the time, many companies were merging to become enterprises, with all the attendant integration woes that come with that transition. Additionally, open source wasn’t a viable option (often for political rather than technical reasons) for large companies. Thus, architects emphasized shared resources and centralized orchestration as a solution.

However, in the intervening years, open source and Linux became viable alternatives, making operating systems commercially free. However, the real tipping point occurred when Linux became operationally free with the advent of tools like Puppet and Chef, which allowed development teams to programmatically spin up their environments as part of an automated build. Once that capability arrived, it fostered an architectural revolution with microservices and the quickly emerging infrastructure of containers and orchestration tools like Kubernetes.

This illustrates that the software development ecosystem expands and evolves in completely unexpected ways. One new capability leads to another one, which unexpectedly creates new capabilities. Over the course of time, the ecosystem completely replaces itself, one piece at a time.

This presents an age-old problem for authors of books about technology generally and software architecture specifically—how can we write something that isn’t old immediately?

We don’t focus on technology or other implementation details in this book. Rather, we focus on how architects make decisions, and how to objectively weigh trade-offs when presented with novel situations. We use contemporaneous scenarios and examples to provide details and context, but the underlying principles focus on trade-off analysis and decision making when faced with new problems.

The Importance of Data in Architecture

Data is a precious thing and will last longer than the systems themselves.

Tim Berners-Lee

It has been said that data is the most important asset in a company. Businesses want to extract value from the data that they have and are finding new ways to deploy data in decision making. Every part of the enterprise is now data driven, from servicing existing customers, to acquiring new customers, increasing customer retention, improving products, predicting sales, and other trends. This reliance on data means that all software architecture is in the service of data, ensuring the right data is available and usable by all parts of the enterprise.

One important distinction that we cover in a variety of chapters is the separation between operational versus analytical data:

- Operational data

- Data used for the operation of the business,including sales, transactional data, inventory, and so on. This data is what the company runs on—if something interrupts this data, the organization cannot function for very long.This type of data is defined as Online Transactional Processing (OLTP), which typically involves inserting, updating, and deleting data in a database.

- Analytical data

- Data used by data scientists and other business analystsfor predictions, trending, and other business intelligence. This data is typically not transactional and often not relational—it may be in a graph database or snapshots in a different format than its original transactional form. This data isn’t critical for the day-to-day operation but rather for the long-term strategic direction and decisions.

We cover the impact of both operational and analytical data throughout the book.

Architectural Decision Records

We will be leveraging ADRs as a way of documenting various architecture decisions made throughout the book. For each architecture decision, we will be using the following ADR format with the assumption that each ADR is approved:

ADR: A short noun phrase containing the architecture decision

Context

In this section of the ADR we will add a short one- or two-sentence description of the problem, and list the alternative solutions.Decision

In this section we will state the architecture decision and provide a detailed justification of the decision.Consequences

In this section of the ADR we will describe any consequences after the decision is applied, and also discuss the trade-offs that were considered.

A list of all the Architectural Decision Records created in this book can be found in Appendix B.

Documenting a decision is important for an architect, but governing the proper

Architecture Fitness Functions

These questions fall under the heading of architecture governance, which applies to any organized oversight of one or more aspects of software development. As this book primarily covers architecture structure, we cover how to automate design and quality principles via fitness functions in many places.

Consider the environments and situations that lead to breakthroughs in automation. In the era before continuous integration, most software projects included a lengthy integration phase. Each developer was expected to work in some level of isolation from others, then integrate all the code at the end into an integration phase. Vestiges of this practice still linger in version control tools that force branching and prevent continuous integration. Not surprisingly, a strong correlation existed between project size and the pain of the integration phase. By pioneering continuous integration, the XP team illustrated the value of rapid, continuous feedback.

The DevOps revolution followed a similar course. As Linux and other open source software became “good enough” for enterprises, combined with the advent of tools that allowed programmatic definition of (eventually) virtual machines, operations personnel realized they could automate machine definitions and many other repetitive tasks.

In both cases, advances in technology and insights led to automating a recurring job that was handled by an expensive role—which describes the current state of architecture governance in most organizations. For example, if an architect chooses a particular architecture style or communication medium, how can they make sure that a developer implements it correctly? When done manually, architects perform code reviews or perhaps hold architecture review boards to assess the state of governance. However, just as in manually configuring computers in operations, important details can easily fall through superficial reviews.

Using Fitness Functions

- Any mechanism

-

Architects can use a wide variety of tools to implement fitness functions; we will show numerous examples throughout the book. For example, dedicated testing libraries exist to test architecture structure, architects can use monitors to test operational architecture characteristics such as performance or scalability, and chaos engineering frameworks test reliability and resiliency.

- Objective integrity assessment

One key enabler for automated governance lies with objective definitions for architecture characteristics. For example, an architect can’t specify that they want a “high performance” website; they must provide an object value that can be measured by a test, monitor, or other fitness function.

Architects must watch out for composite architecture characteristics—onesthat aren’t objectively measurable but are really composites of other measurable things. For example, “agility” isn’t measurable, but if an architect starts pulling the broad term agility apart, the goal is for teams to be able to respond quickly and confidently to change, either in ecosystem or domain. Thus, an architect can find measurable characteristics that contribute to agility: deployability, testability, cycle time, and so on. Often, the lack of ability to measure an architecture characteristic indicates too vague a definition. If architects strive toward measurable properties, it allows them to automate fitness function application.- Some architecture characteristic or combination of architecture characteristics

This characteristic describes the two scopes for fitness functions:

- Atomic

- These fitness functions handle a single architecture characteristic in isolation.For example, a fitness function that checks for component cycles within a codebase is atomic in scope.

- Holistic

- Holistic fitness functions validate a combination ofarchitecture characteristics. A complicating feature of architecture characteristics is the synergy they sometimes exhibit with other architecture characteristics. For example, if an architect wants to improve security, a good chance exists that it will affect performance. Similarly, scalability and elasticity are sometimes at odds—supporting a large number of concurrent users can make handling sudden bursts more difficult. Holistic fitness functions exercise a combination of interlocking architecture characteristics to ensure that the combined effect won’t negatively affect the architecture.

An architect implements fitness functions to build protections around unexpected change in architecture characteristics. In the Agile software development world, developers implement unit, functional, and user acceptance tests to validate different dimensions of the domain design. However, until now, no similar mechanism existed to validate the architecture characteristics part of the design. In fact, the separation between fitness functions and unit tests provides a good scoping guideline for architects. Fitness functions validate architecture characteristics, not domain criteria; unit tests are the opposite. Thus, an architect can decide whether a fitness function or unit test is needed by asking the question: “Is any domain knowledge required to execute this test?” If the answer is “yes,” then a unit/function/user acceptance test is appropriate; if “no,” then a fitness function is needed.

For example, when architects talk about elasticity, it’s the ability of the application to withstand a sudden burst of users. Notice that the architect doesn’t need to know any details about the domain—this could be an ecommerce site, an online game, or something else. Thus, elasticity is an architectural concern and within the scope of a fitness function. If on the other hand the architect wanted to validate the proper parts of a mailing address, that is covered via a traditional test. Of course, this separation isn’t purely binary—some fitness functions will touch on the domain and vice versa, but the differing goals provide a good way to mentally separate them.

Here are a couple of examples to make the concept less abstract.

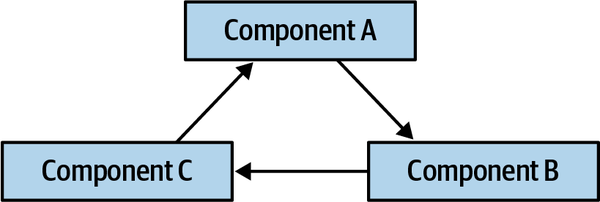

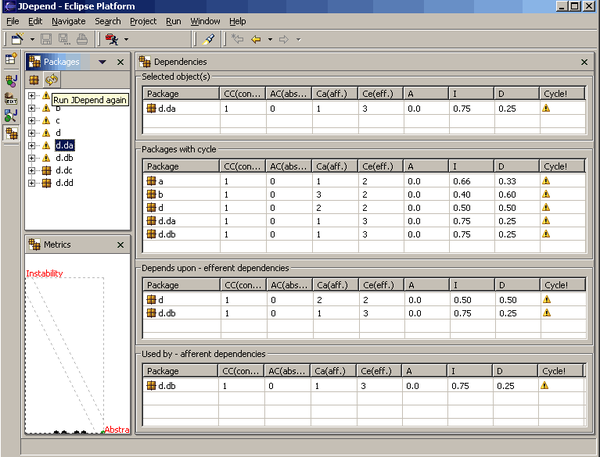

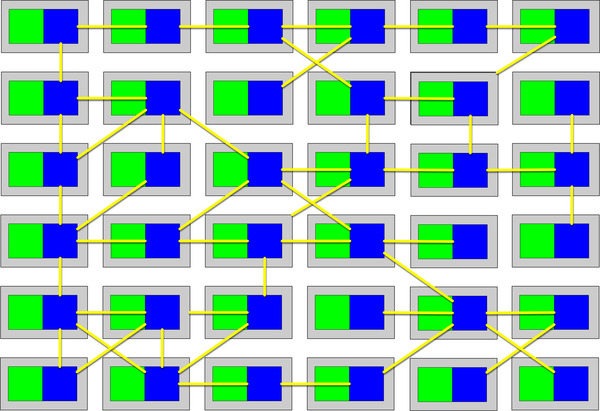

Figure 1-1. Cyclic dependencies between components

In this anti-pattern, each component references something in the others. Having a network of components such as this damages modularity because a developer cannot reuse a single component without also bringing the others along. And, of course, if the other components are coupled to other components, the architecture tends more and more toward the Big Ball of Mud anti-pattern. How can architects govern this behavior without constantly looking over the shoulders of trigger-happy developers? Code reviews help but happen too late in the development cycle to be effective. If an architect allows a development team to rampantly import across the codebase for a week until the code review, serious damage has already occurred in the codebase.

The solution to this problem is to write a fitness function to avoid component cycles, as shown in Example 1-1.

Example 1-1. Fitness function to detect component cycles

publicclassCycleTest{privateJDependjdepend;@BeforeEachvoidinit(){jdepend=newJDepend();jdepend.addDirectory("/path/to/project/persistence/classes");jdepend.addDirectory("/path/to/project/web/classes");jdepend.addDirectory("/path/to/project/thirdpartyjars");}@TestvoidtestAllPackages(){Collectionpackages=jdepend.analyze();assertEquals("Cycles exist",false,jdepend.containsCycles());}}

In the code, an architect uses the metrics tool JDepend to

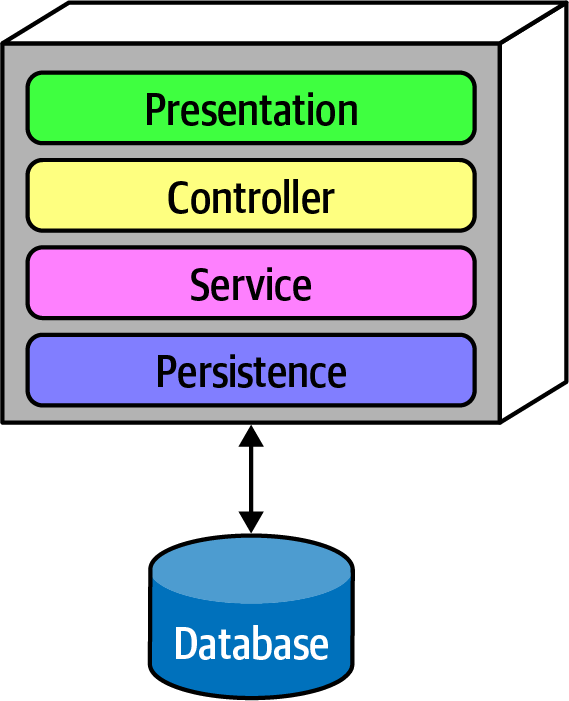

Figure 1-2. Traditional layered architecture

However, how can the architect ensure that developers will respect these layers? Some developers may not understand the importance of the patterns, while others may adopt a “better to ask forgiveness than permission” attitude because of some overriding local concern, such as performance. But allowing implementers to erode the reasons for the architecture hurts the long-term health of the architecture.

ArchUnit allows architects to address this problem via a fitness function, shown in Example 1-2.

Example 1-2. ArchUnit fitness function to govern layers

layeredArchitecture().layer("Controller").definedBy("..controller..").layer("Service").definedBy("..service..").layer("Persistence").definedBy("..persistence..").whereLayer("Controller").mayNotBeAccessedByAnyLayer().whereLayer("Service").mayOnlyBeAccessedByLayers("Controller").whereLayer("Persistence").mayOnlyBeAccessedByLayers("Service")

In Example 1-2, the architect defines the desirable relationship between layers and writes a verification fitness function to govern it. This allows an architect to establish architecture principles outside the diagrams and other informational artifacts, and verify them on an ongoing basis.

A similar tool in the .NET space,

Example 1-3. NetArchTest for layer dependencies

// Classes in the presentation should not directly reference repositoriesvarresult=Types.InCurrentDomain().That().ResideInNamespace("NetArchTest.SampleLibrary.Presentation").ShouldNot().HaveDependencyOn("NetArchTest.SampleLibrary.Data").GetResult().IsSuccessful;

Tools continue to appear in this space with increasing degrees of sophistication. We will continue to highlight many of these techniques as we illustrate fitness functions alongside many of our solutions.

Finding an objective outcome for a fitness function is critical.

Imagine an alternative world in which every project runs a deployment pipeline, and the security team has a “slot” in each team’s deployment pipeline where they can deploy fitness functions. Most of the time, these will be mundane checks for safeguards like preventing developers from storing passwords in databases and similar regular governance chores. However, when a zero-day exploit appears, having the same mechanism in place everywhere allows the security team to insert a test in every project that checks for a certain framework and version number; if it finds the dangerous version, it fails the build and notifies the security team. Teams configure deployment pipelines to awaken for any change to the ecosystem: code, database schema, deployment configuration, and fitness functions. This allows enterprises to universally automate important governance tasks.

Fitness functions provide many benefits for architects, not the least of which is the chance to do some coding again! One of the universal complaints among architects is that they don’t get to code much anymore—but fitness functions are often code! By building an executable specification of the architecture, which anyone can validate anytime by running the project’s build, architects must understand the system and its ongoing evolution well, which overlaps with the core goal of keeping up with the code of the project as it grows.

Architecture Versus Design: Keeping Definitions Simple

Second, by focusing on architecture concepts, we can avoid the numerous implementations of those concepts. Architects can implement asynchronous communication in a variety of ways; we focus on why an architect would choose asynchronous communication and leave the implementation details to another place.

Third, if we start down the path of implementing all the varieties of options we show, this would be the longest book ever written. Focus on architecture principles allows us to keep things as generic as they can be.

- Service

- In colloquial terms, a service is a cohesive collection of functionalitydeployed as an independent executable. Most of the concepts we discuss with regard to services apply broadly to distributed architectures, and specifically microservices architectures.In the terms we define inChapter 2, a service is part of an architecture quantum, which includes further definitions of both static and dynamic coupling between services and other quanta.

- Coupling

-

Two artifacts (including services) are coupled if a change in one might require a change in the other to maintain proper functionality.

- Component

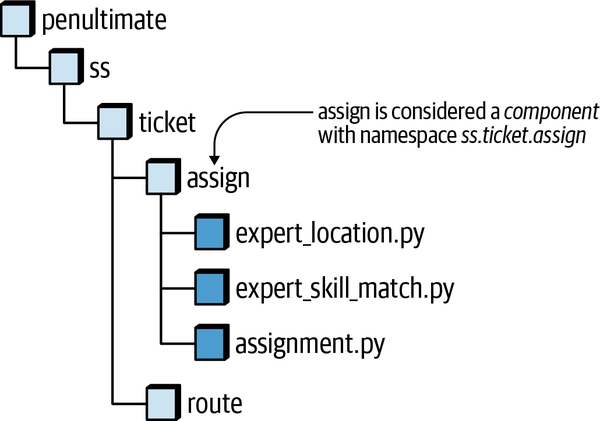

- An architectural building block of the application that does some sort of business or infrastructure function,usually manifested through a package structure (Java), namespace (C#), or a physical grouping of source code files within some sort of directory structure. For example, the component Order History might be implemented through a set of class files located in the namespace

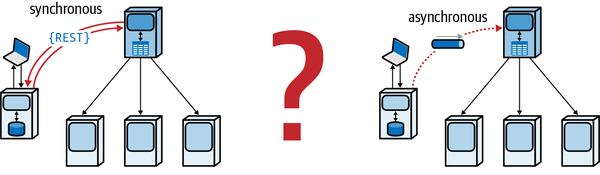

app.business.order.history. - Synchronous communication

- Two artifacts communicate synchronously if the caller must wait for the response before proceeding.

- Asynchronous communication

- Two artifacts communicate asynchronously if the caller does not wait for theresponse before proceeding. Optionally, the caller can be notified by the receiver through a separate channel when the request has completed.

- Orchestrated coordination

- A workflow is orchestrated if it includes a service whose primary responsibility is to coordinate the workflow.

- Choreographed coordination

- A workflow is choreographed when it lacks an orchestrator;rather, the services in the workflow share the coordination responsibilities of the workflow.

- Atomicty

- A workflow is atomic if all parts of the workflow maintain aconsistent state at all times; the opposite is represented by the spectrum of eventual consistency, covered inChapter 6.

- Contract

-

We use the term contract broadly to define the interface between two

software parts, which may encompass method or function calls, integration architecture remote calls, dependencies, and so on. Anywhere two pieces of software join, a contract is involved.

Introducing the Sysops Squad Saga

- saga

A long story of heroic achievement.

Oxford English Dictionary

We use the Sysops Squad saga within each chapter to illustrate the techniques and trade-offs described in this book. While many books on software architecture cover new development efforts, many real-world problems exist within existing systems. Therefore, our story starts with the existing Sysops Squad architecture highlighted here.

Penultimate Electronics is a large electronics giant that has numerous retail stores throughout the country. When customers buy computers, TVs, stereos, and other electronic equipment, they can choose to purchase a support plan. When problems occur, customer-facing technology experts (the Sysops Squad) come to the customer’s residence (or work office) to fix problems with the electronic device.

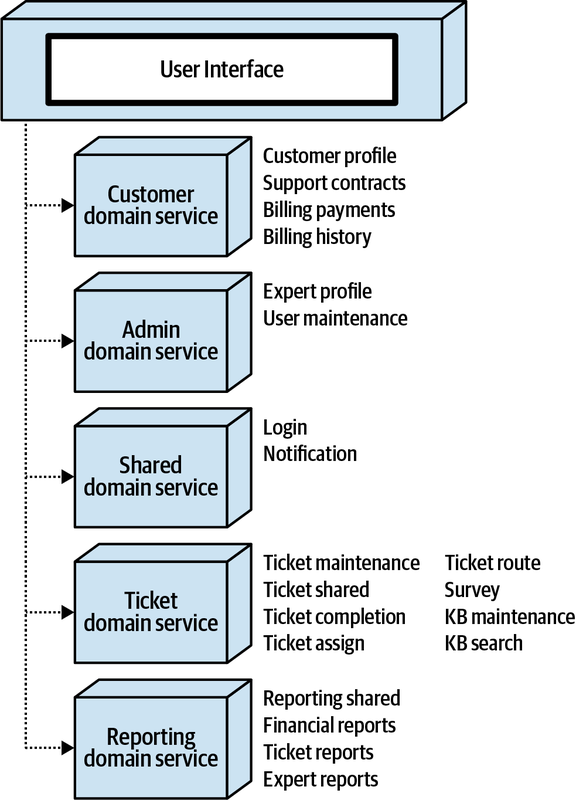

The four main users of the Sysops Squad ticketing application are as follows:

- Administrator

-

The administrator maintains the internal users of the system, including the list of experts and their corresponding skill set, location, and availability. The administrator also manages all of the billing processing for customers using the system, and maintains static reference data (such as supported products, name-value pairs in the system, and so on).

- Customer

-

The customer registers for the Sysops Squad service and maintains their customer profile, support contracts, and billing information. Customers enter problem tickets into the system, and also fill out surveys after the work has been completed.

- Sysops Squad expert

-

Experts are assigned problem tickets and fix problems based on the ticket. They also interact with the knowledge base to search for solutions to customer problems and enter notes about repairs.

- Manager

-

The manager keeps track of problem ticket operations and receives operational and analytical reports about the overall Sysops Squad problem ticket system.

Nonticketing Workflow

-

Sysops Squad experts are added and maintained in the system through an administrator, who enters in their locale, availability, and skills.

-

Customers register with the Sysops Squad system and have multiple support plans based on the products they purchased.

-

Customers are automatically billed monthly based on credit card information contained in their profile. Customers can view billing history and statements through the system.

-

Managers request and receive various operational and analytical reports, including financial reports, expert performance reports, and ticketing reports.

Ticketing Workflow

-

Customers who have purchased the support plan enter a problem ticket by using the Sysops Squad website.

-

Once a problem ticket is entered in the system, the system then determines which Sysops Squad expert would be the best fit for the job based on skills, current location, service area, and availability.

-

Once assigned, the problem ticket is uploaded to a dedicated custom mobile app on the Sysops Squad expert’s mobile device. The expert is also notified via a text message that they have a new problem ticket.

-

The customer is notified through an SMS text message or email (based on their profile preference) that the expert is on their way.

-

The expert uses the custom mobile application on their phone to retrieve the ticket information and location. The Sysops Squad expert can also access a knowledge base through the mobile app to find out what has been done in the past to fix the problem.

-

Once the expert fixes the problem, they mark the ticket as “complete.” The sysops squad expert can then add information about the problem and repair the knowledge base.

-

After the system receives notification that the ticket is complete, it sends an email to the customer with a link to a survey, which the customer then fills out.

-

The system receives the completed survey from the customer and records the survey information.

A Bad Scenario

Change is also difficult and risky in this large monolith. Whenever a change is made, it usually takes too long and something else usually breaks. Because of reliability issues, the Sysops Squad system frequently “freezes up,” or crashes, resulting in all application functionality not being available anywhere from five minutes to two hours while the problem is identified and the application restarted.

If something isn’t done soon, Penultimate Electronics will be forced to abandon the very lucrative support contract business line and lay off all the Sysops Squad administrators, experts, managers, and IT development staff—including the architects.

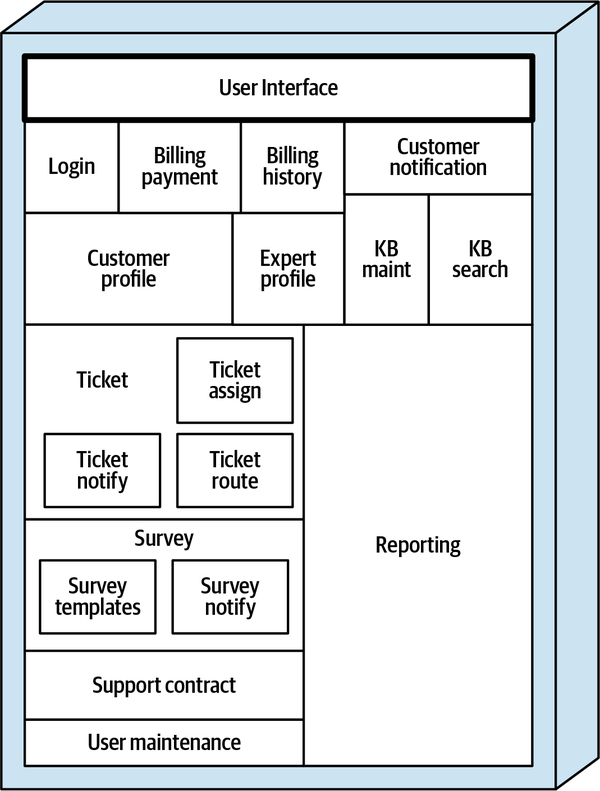

Sysops Squad Architectural Components

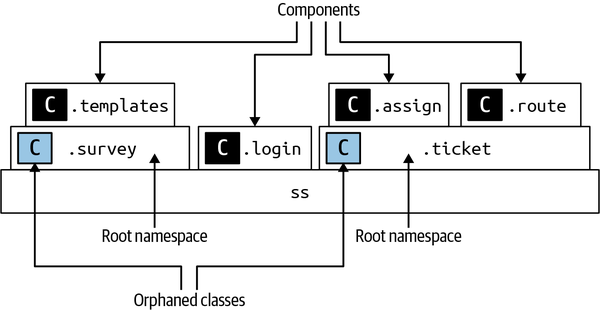

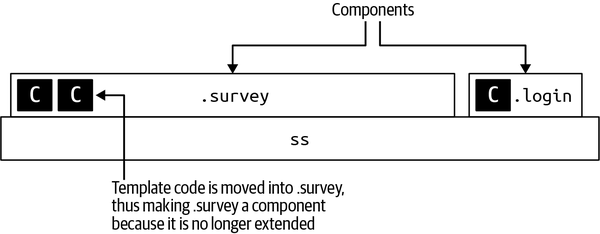

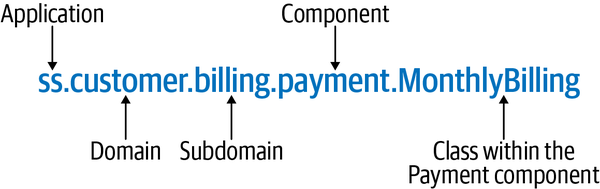

ss. part of the namespace specifies the Sysops Squad application context).

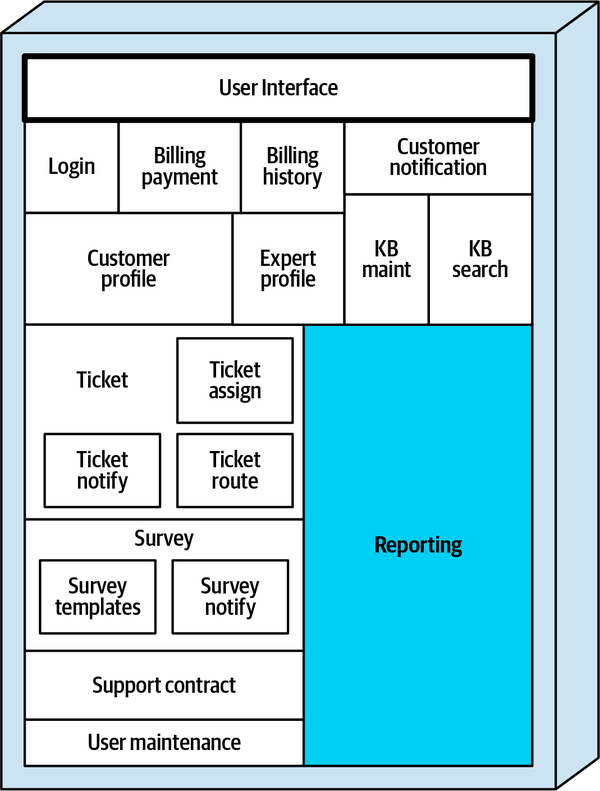

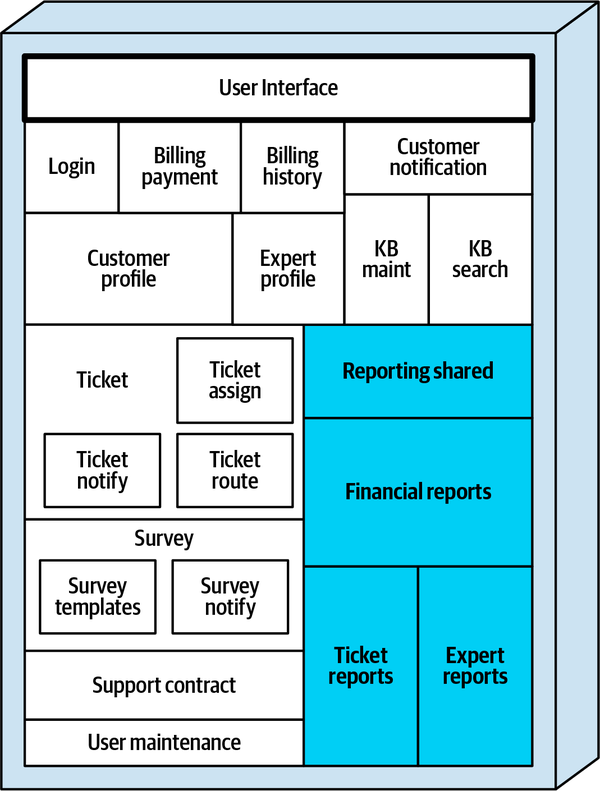

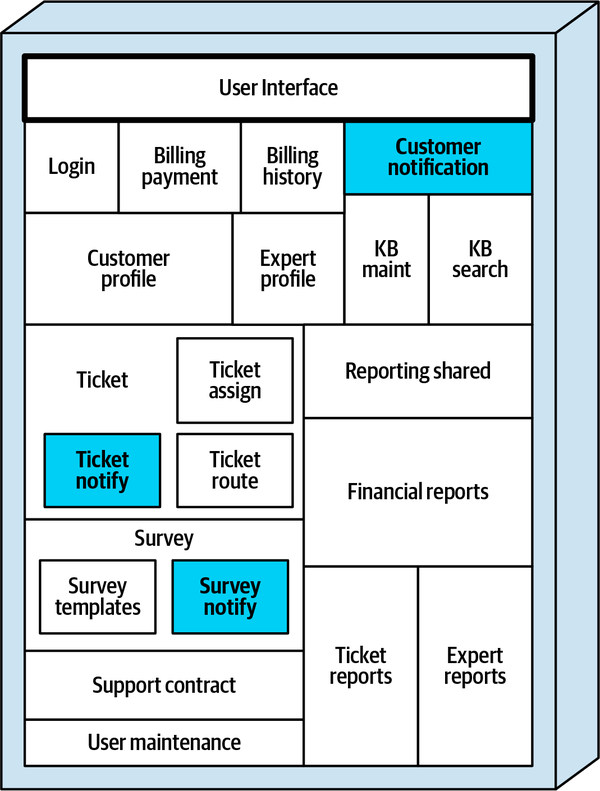

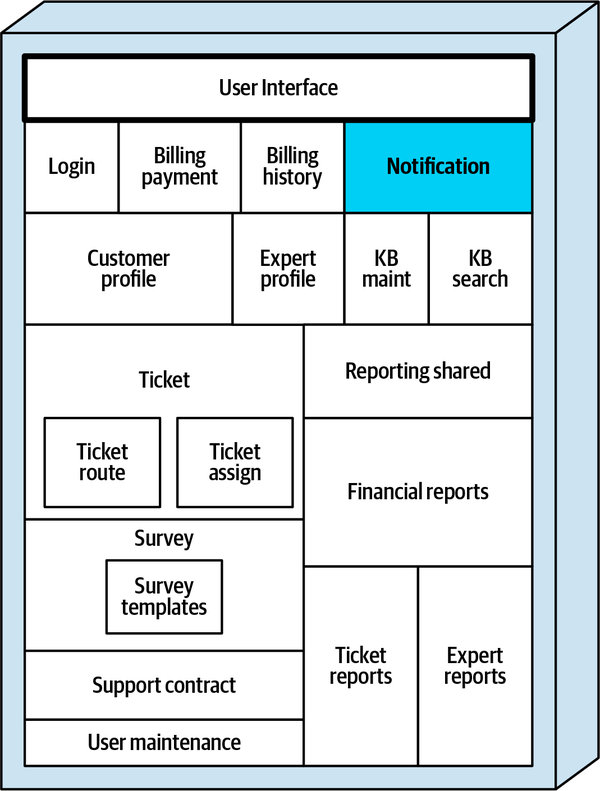

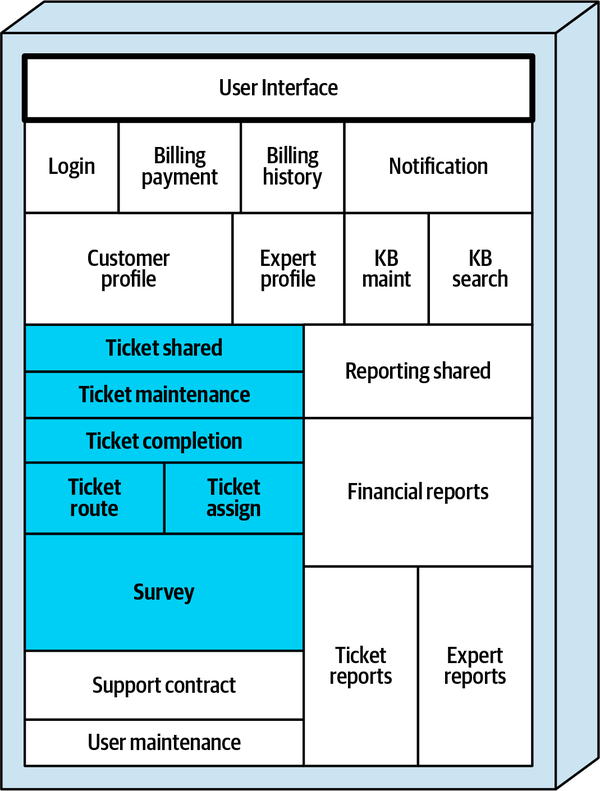

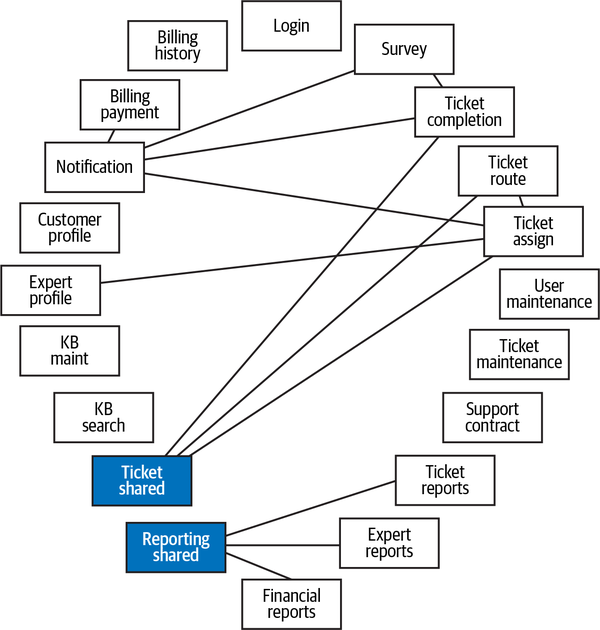

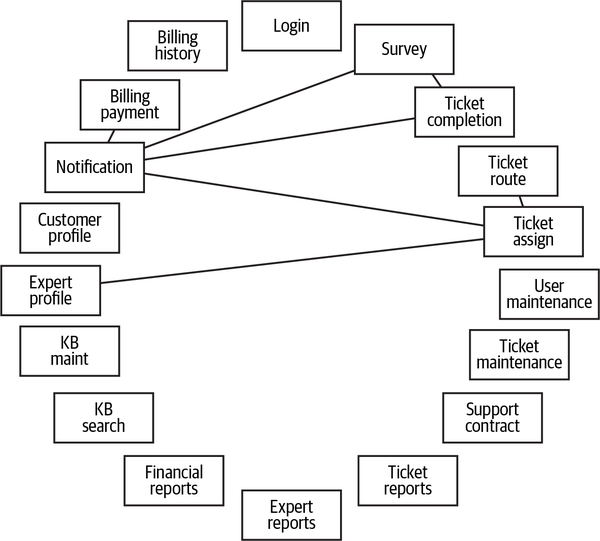

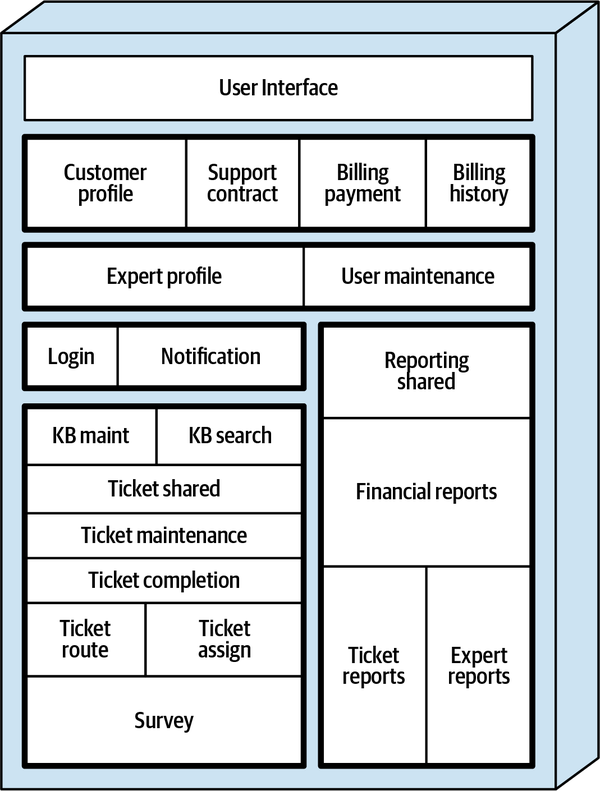

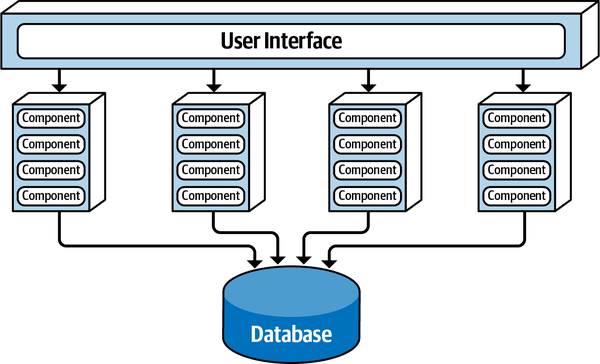

Figure 1-3. Components within the existing Sysops Squad application

| Component | Namespace | Responsibility |

|---|---|---|

Login |

| Internal user and customer login and security logic |

Billing payment |

| Customer monthly billing and customer credit card info |

Billing history |

| Payment history and prior billing statements |

Customer notification |

| Notify customer of billing, general info |

Customer profile |

| Maintain customer profile, customer registration |

Expert profile |

| Maintain expert profile (name, location, skills, etc.) |

KB maint |

| Maintain and view items in the knowledge base |

KB search |

| Query engine for searching the knowledge base |

Reporting |

| All reporting (experts, tickets, financial) |

Ticket |

| Ticket creation, maintenance, completion, common code |

Ticket assign |

| Find an expert and assign the ticket |

Ticket notify |

| Notify customer that the expert is on their way |

Ticket route |

| Send the ticket to the expert’s mobile device app |

Support contract |

| Support contracts for customers, products in the plan |

Survey |

| Maintain surveys, capture and record survey results |

Survey notify |

| Send survey email to customer |

Survey templates |

| Maintain various surveys based on type of service |

User maintenance |

| Maintain internal users and roles |

These components will be used in subsequent chapters to illustrate various techniques and trade-offs when dealing with breaking applications into distributed architectures.

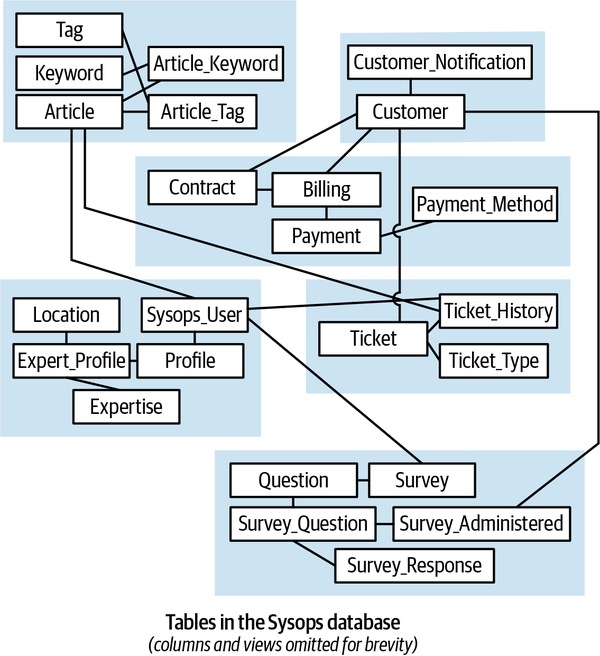

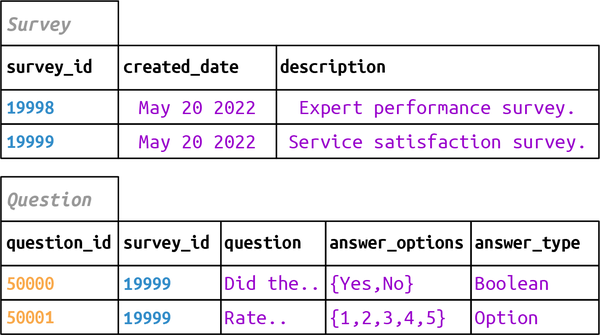

Sysops Squad Data Model

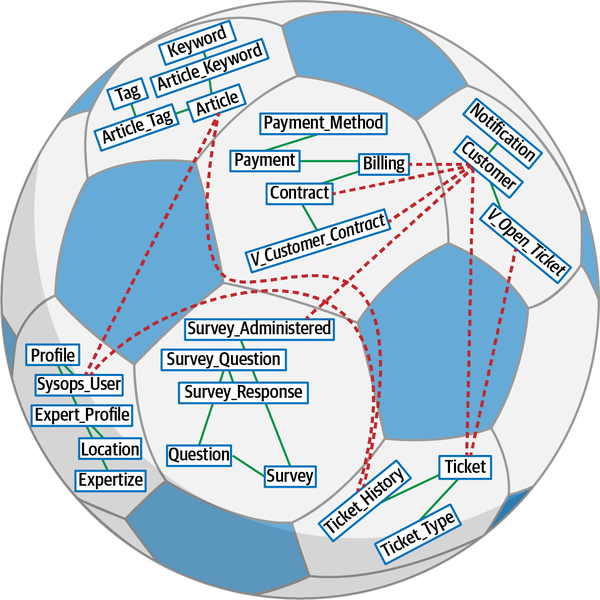

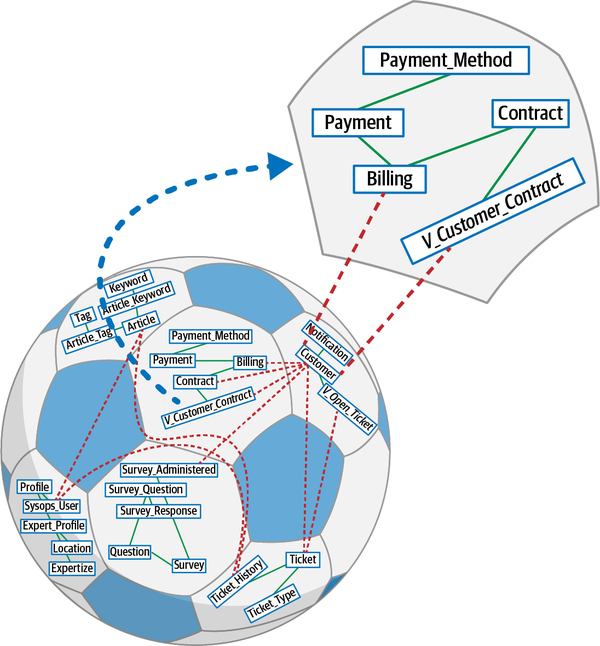

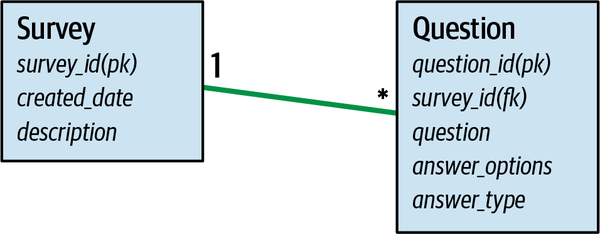

The Sysops Squad application with its various components listed in Table 1-1

Figure 1-4. Data model within the existing Sysops Squad application

| Table | Responsibility |

|---|---|

Customer | Entities needing Sysops support |

Customer_Notification | Notification preferences for customers |

Survey | A survey for after-support customer satisfaction |

Question | Questions in a survey |

Survey_Question | A question is assigned to the survey |

Survey_Administered | Survey question is assigned to customer |

Survey_Response | A customer’s response to the survey |

Billing | Billing information for support contract |

Contract | A contract between an entity and Sysops for support |

Payment_Method | Payment methods supported for making payment |

Payment | Payments processed for billings |

SysOps_User | The various users in Sysops |

Profile | Profile information for Sysops users |

Expert_Profile | Profiles of experts |

Expertise | Various expertise within Sysops |

Location | Locations served by the expert |

Article | Articles for the knowledge base |

Tag | Tags on articles |

Keyword | Keyword for an article |

Article_Tag | Tags associated to articles |

Article_Keyword | Join table for keywords and articles |

Ticket | Support tickets raised by customers |

Ticket_Type | Different types of tickets |

Ticket_History | The history of support tickets |

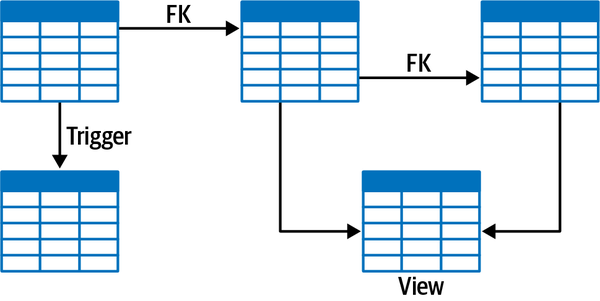

The Sysops data model is a standard third normal form data model with only a few stored procedures or triggers. However, a fair number of views exist that are mainly used by the Reporting component. As the architecture team tries to break up the application and move toward distributed architecture, it will have to work with the database team to accomplish the tasks at the database level. This setup of database tables and views will be used throughout the book to discuss various techniques and trade-offs to accomplish the task of breaking apart the database.

Part I. Pulling Things Apart

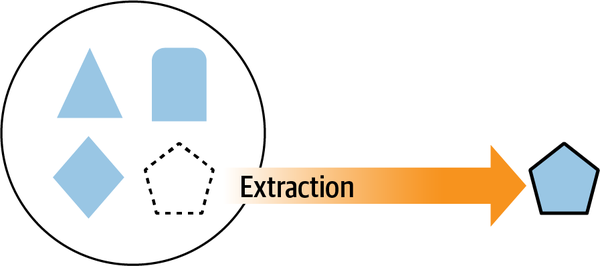

As many of us discovered when we were children, a great way to understand how something fits together is to first pull it apart. To understand complex subjects (such as trade-offs in distributed architectures), an architect must figure out where to start untangling.

In the book What Every Programmer Should Know About Object-Oriented Design (Dorset House), Meilir Page-Jones

Our goal is to investigate how to do trade-off analysis in distributed architectures; to do that, we must pull the moving pieces apart so that we can discuss them in isolation to understand them fully before putting them back together.

Data and transactions have become increasingly important in architecture, driving many trade-off decisions by architects and DBAs. Chapter 6 addresses the architectural impacts of data, including how to reconcile service and data boundaries. Finally, Chapter 7 ties together architecture coupling with data concerns to define integrators and disintegrators—forces that encourage a larger or smaller service size and boundary.

Chapter 2. Discerning Coupling in Software Architecture

Wednesday, November 3, 13:00

Logan, the lead architect for Penultimate Electronics, interrupted a small group of architects in the cafeteria, discussing distributed architectures. “Austen, are you wearing a cast again?”

“No, it’s just a splint,” replied Austen. “I sprained my wrist playing extreme disc golf over the weekend—it’s almost healed.”

“What is…never mind. What is this impassioned conversation I barged in on?”

“Why wouldn’t someone always choose the saga pattern in microservices to wire together transactions?” asked Austen. “That way, architects can make the services as small as they want.”

“But don’t you have to use orchestration with sagas?” asked Addison. “What about times when we need asynchronous communication? And, how complex will the transactions get? If we break things down too much, can we really guarantee data fidelity?”

“You know,” said Austen, “if we use an enterprise service bus, we can get it to manage most of that stuff for us.”

“I thought no one used ESBs anymore—shouldn’t we use Kafka for stuff like that?”

“They aren’t even the same thing!” said Austen.

Logan interrupted the increasingly heated conversation. “It is an apples-to-oranges comparison, but none of these tools or approaches is a silver bullet. Distributed architectures like microservices are difficult, especially if architects cannot untangle all the forces at play. What we need is an approach or framework that helps us figure out the hard problems in our architecture.”

“Well,” said Addison, “whatever we do, it has to be as decoupled as possible—everything I’ve read says that architects should embrace decoupling as much as possible.”

“If you follow that advice,” said Logan, “Everything will be so decoupled that nothing can communicate with anything else—it’s hard to build software that way! Like a lot of things, coupling isn’t inherently bad; architects just have to know how to apply it appropriately. In fact, I remember a famous quote about that from a Greek philosopher….”

All things are poison, and nothing is without poison; the dosage alone makes it so a thing is not a poison.

Paracelsus

One of the most difficult tasks an architect will face is untangling the various forces and trade-offs at play in distibuted architectures.

Architects struggle with granularity and communication decisions because there are no clear universal guides for making decisions—no best practices exist that can apply to real-world complex systems. Until now, architects lacked the correct perspective and terminology to allow a careful analysis that could determine the best (or least worst) set of trade-offs on a case-by-case basis.

Why have architects struggled with decisions in distributed architectures? After all, we’ve been building distributed systems since the last century, using many of the same mechanisms (message queues, events, and so on). Why has the complexity ramped up so much with microservices?

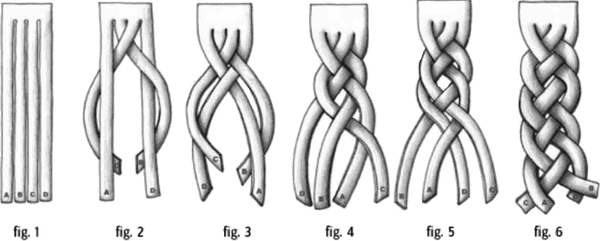

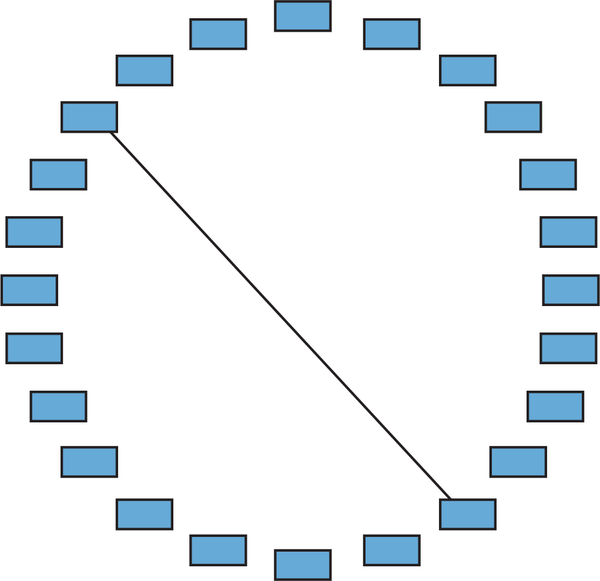

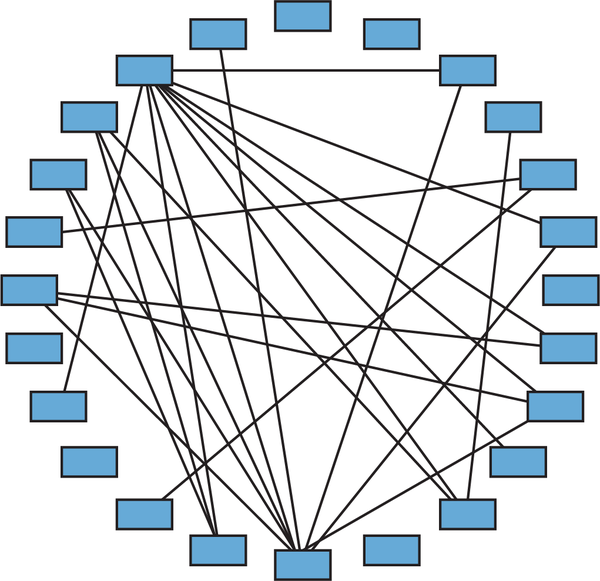

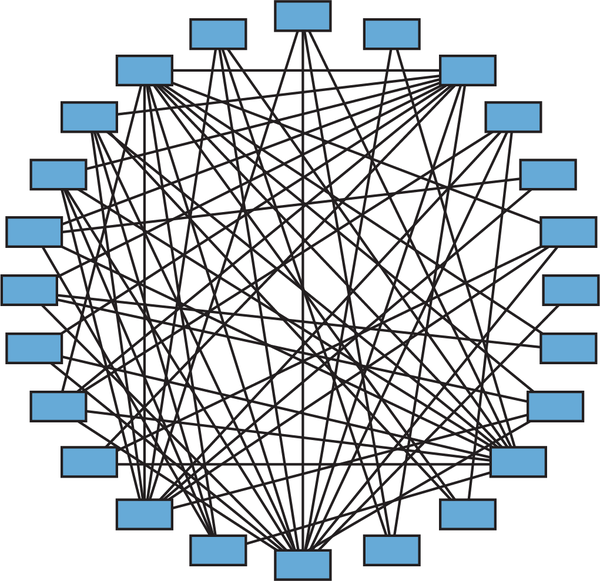

This book focuses on how architects can perform trade-off analysis for any number of scenarios unique to their situation. As in many things in architecture, the advice is simple; the hard parts lie in the details, particularly how difficult parts become entangled, making it difficult to see and understand the individual parts, as illustrated in Figure 2-1.

Figure 2-1. A braid entangles hair, making the individual strands hard to identify

When architects look at entangled problems, they struggle with performing trade-off analysis because of the difficulties separating the concerns, so that they may consider them independently. Thus, the first step in trade-off analysis is untangle the dimensions of the problem, analyzing what parts are coupled to one another and what impact that coupling has on change. For this purpose, we use the simplest definition of the word coupling:

- Coupling

-

Two parts of a software system are coupled if a change in one might cause a change in the other.

Often, software architecture creates multidimensional problems, where multiple forces all interact in interdependent ways. To analyze trade-offs, an architect must first determine what forces need to trade off with each other.

Thus, here’s our advice for modern trade-off analysis in software architecture:

-

Find what parts are entangled together.

-

Analyze how they are coupled to one another.

-

Assess trade-offs by determining the impact of change on interdependent systems.

While the steps are simple, the hard parts lurk in the details. Thus, to illustrate this framework in practice, we take one of the most difficult (and probably the closest to generic) problems in distributed architectures, which is related to microservices:

- How do architects determine the size and communication styles for microservices?

-

Determining the proper size for microservices seems a pervasive problem—too-small services create transactional and orchestration issues, and too-large services create scale and distribution issues.

To that end, the remainder of this book untangles the many aspects to consider when answering the preceding question. We provide new terminology to differentiate similar but distinct patterns and show practical examples of applying these and other patterns.

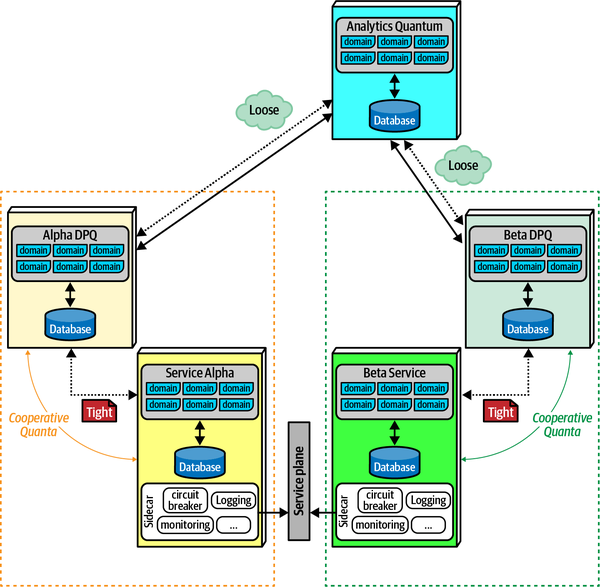

Architecture (Quantum | Quanta)

An architecture quantum measures several aspects of both topology and behavior in software architecture related to how parts connect and communicate with one another:

- Architecture quantum

- An architecture quantum is an independently deployable artifact with high functional cohesion,high static coupling, and synchronous dynamic coupling. A common example of an architecture quantum is a well-formed microservice within a workflow.

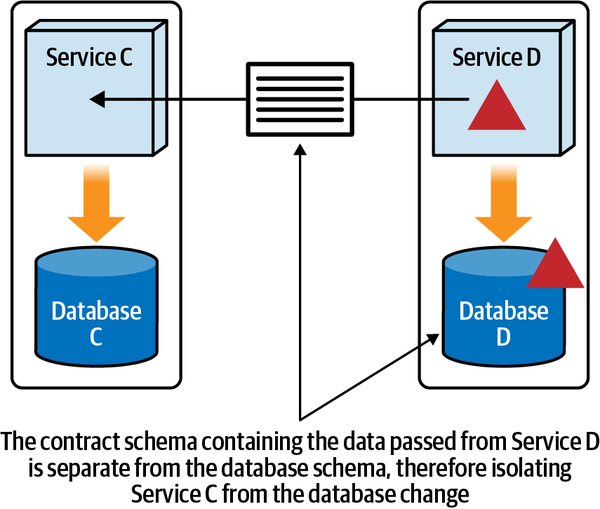

- Static coupling

- Represents how static dependencies resolve within the architecture viacontracts. These dependencies include operating system, frameworks, and/or libraries delivered via transitive dependency management, and any other operational requirement to allow the quantum to operate.

- Dynamic coupling

- Represents how quanta communicate at runtime, either synchronouslyor asynchronously. Thus, fitness functions for these characteristics must be continuous, typically utilizing monitors.

These definitions include important characteristics; let’s cover each in detail as they inform most of the examples in the book.

Independently Deployable

Making each architecture quantum represent a deployable asset within the architecture serves several useful purposes. First, the boundary represented by an architecture quantum serves as a useful common language among architects, developers, and operations. Each understands the common scope under question: architects understand the coupling characteristics, developers understand the scope of behavior, and the operations team understands the deployable characteristics.

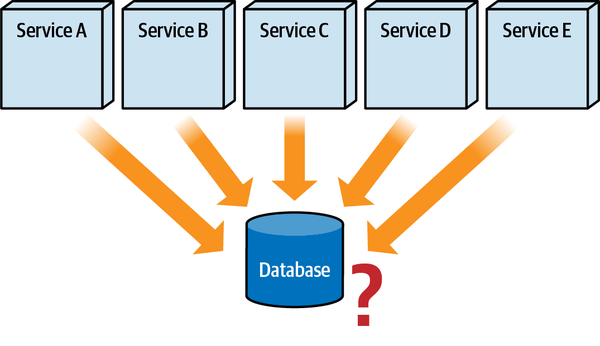

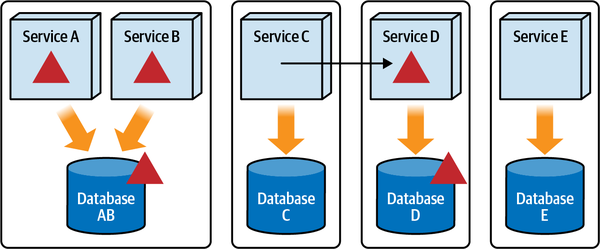

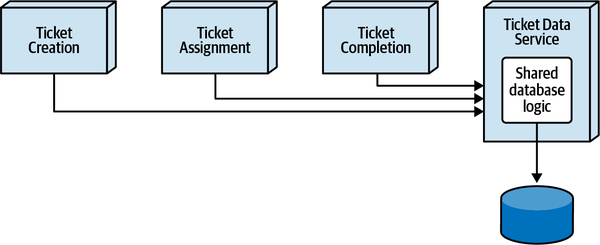

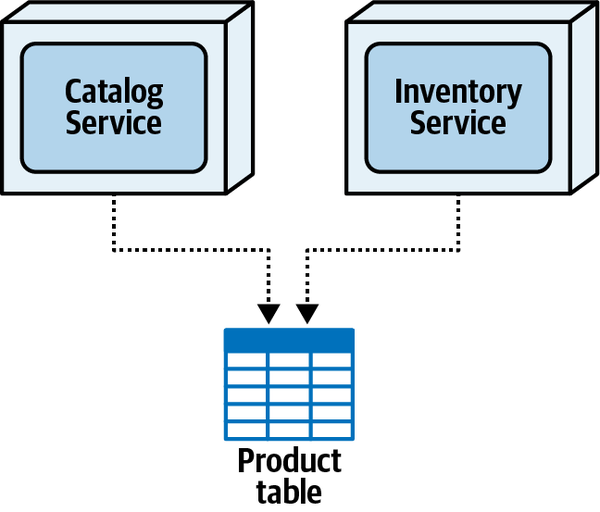

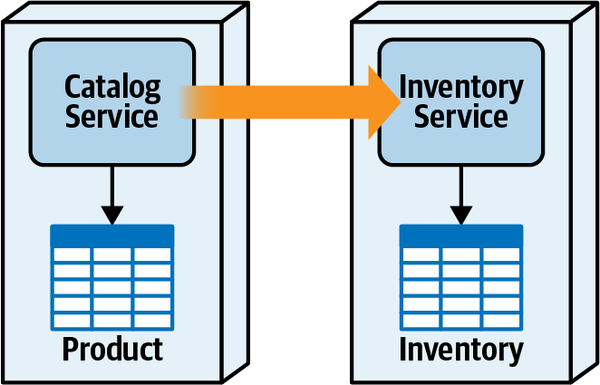

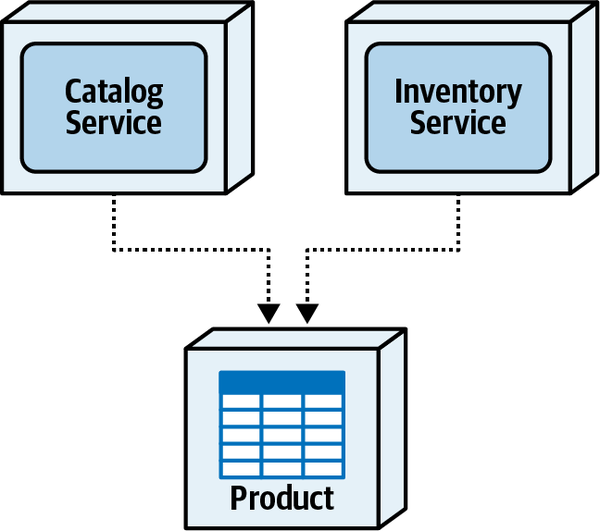

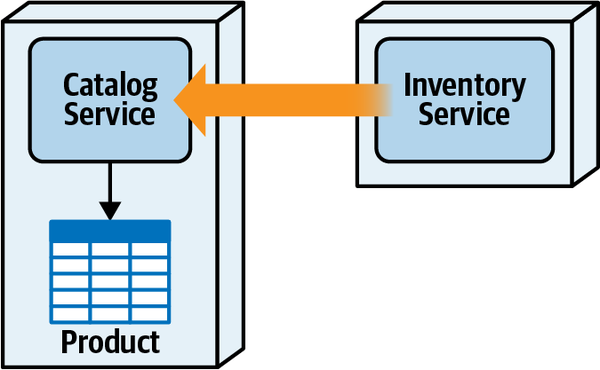

Third, independent deployability forces the architecture quantum to include common coupling points such as databases. Most discussions about architecture conveniently ignore issues such as databases and user interfaces, but real-world systems must commonly deal with those problems. Thus, any system that uses a shared database fails the architecture quantum criteria for independent deployment unless the database deployment is in lockstep with the application. Many distributed systems that would otherwise qualify for multiple quanta fail the independently deployable part if they share a common database that has its own deployment cadence. Thus, merely considering the deployment boundaries doesn’t solely provide a useful measure. Architects should also consider the second criteria for an architecture quantum, high functional cohesion, to limit the architecture quantum to a useful scope.

High Functional Cohesion

High functional cohesion refers structurally to the proximity

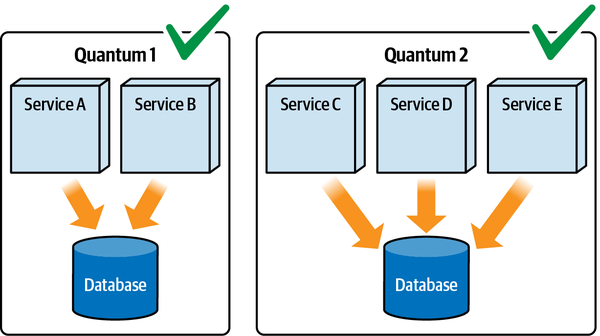

High Static Coupling

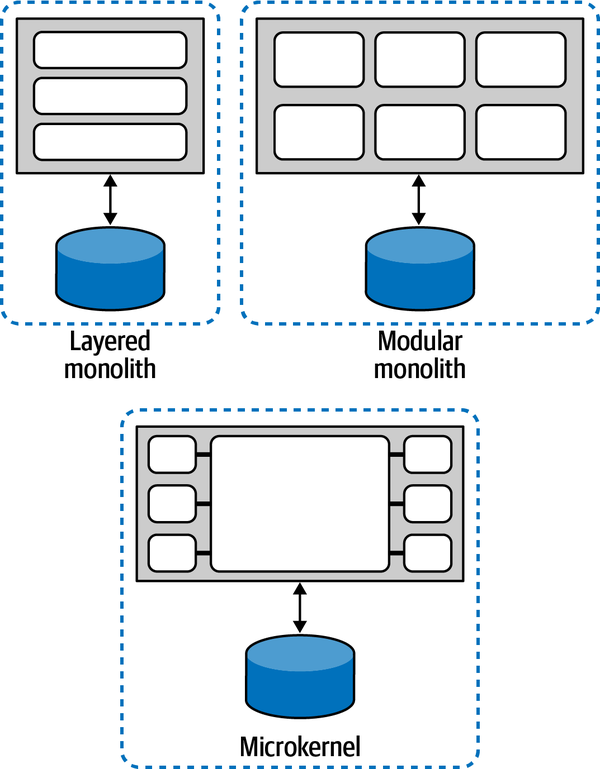

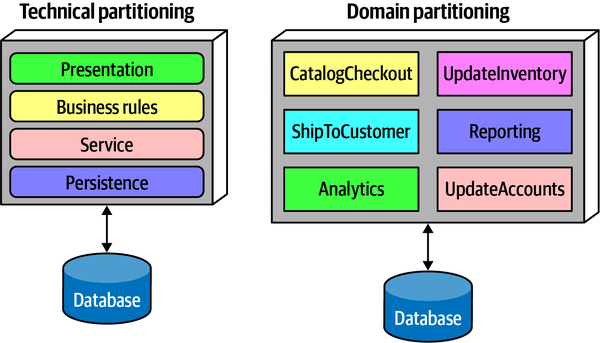

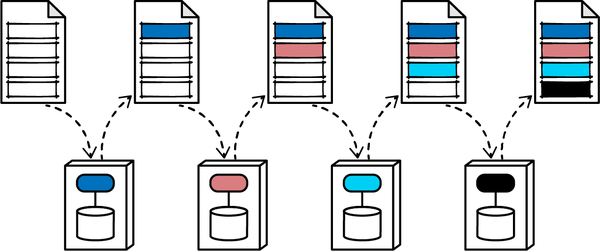

An architecture quantum is, in part, a measure of static coupling, and the measure is quite simple for most architecture topologies. For example, the following diagrams show the architecture styles featured in Fundamentals of Software Architecture, with the architecture quantum static coupling illustrated.

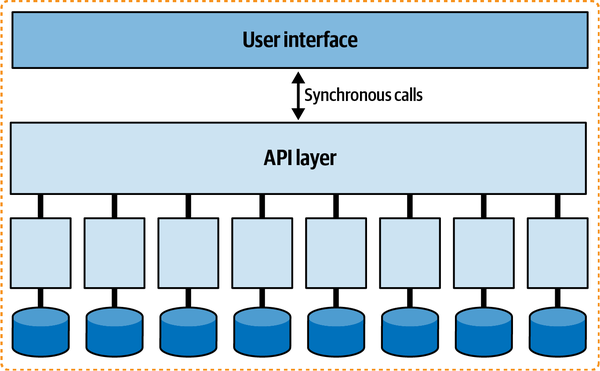

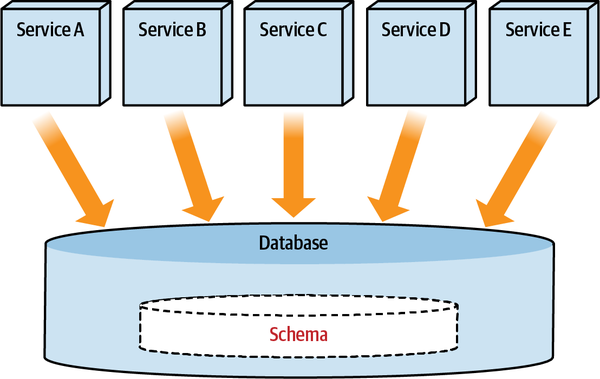

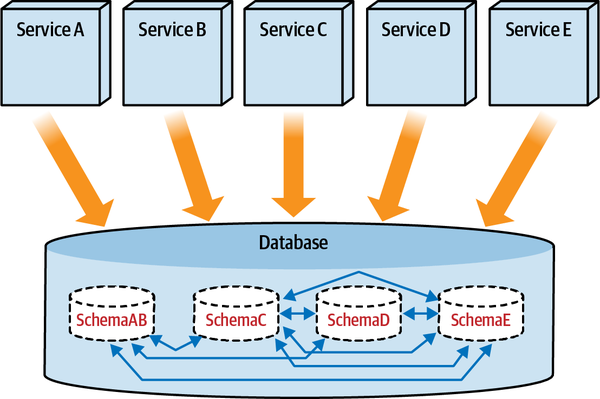

Any of the monolithic architecture styles will necessarily have a

Figure 2-2. Monolithic architectures always have a quantum of one

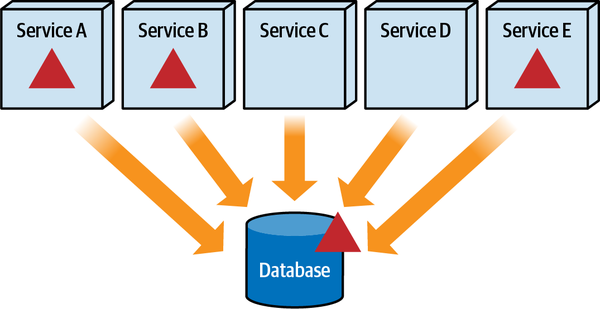

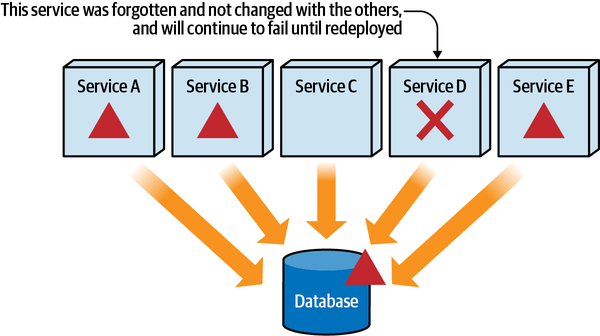

As you can see, any architecture that deploys as a single unit and utilizes a single database will always have a single quantum. The architecture quantum measure of static coupling includes the database, and a system that relies on a single database cannot have more than a single quantum. Thus, the static coupling measure of an architecture quantum helps identify coupling points in architecture, not just within the software components under development. Most monolithic architectures contain a single coupling point (typically, a database) that makes its quantum measure one.

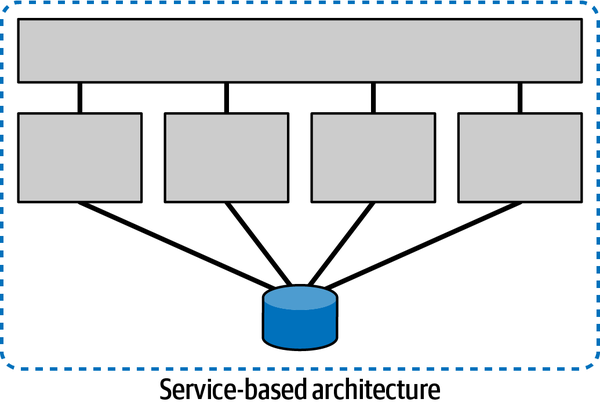

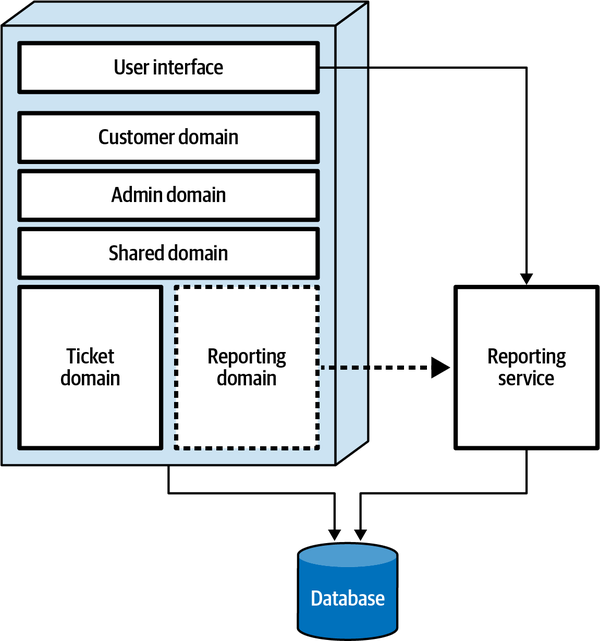

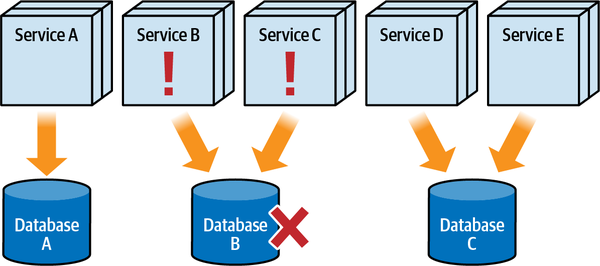

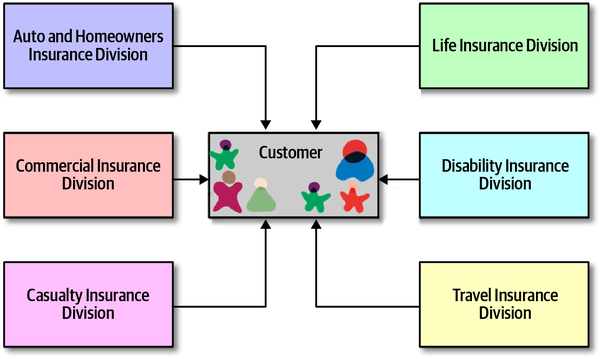

Distributed architectures often feature decoupling at the component level;

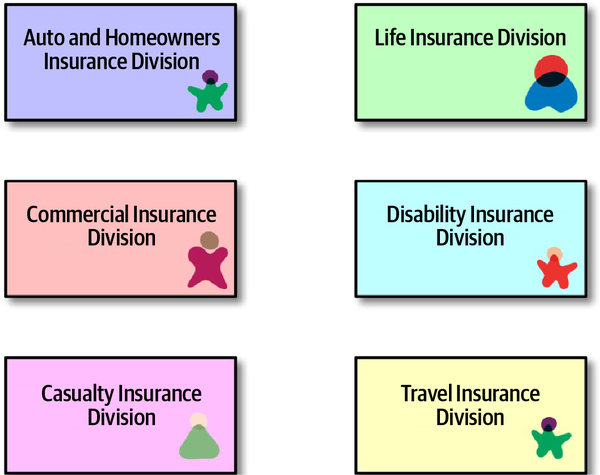

Figure 2-3. Architecture quantum for a service-based architecture

While this individual services model shows the isolation common in microservices, the architecture still utilizes a single relational database, rendering its architecture quantum score to one.

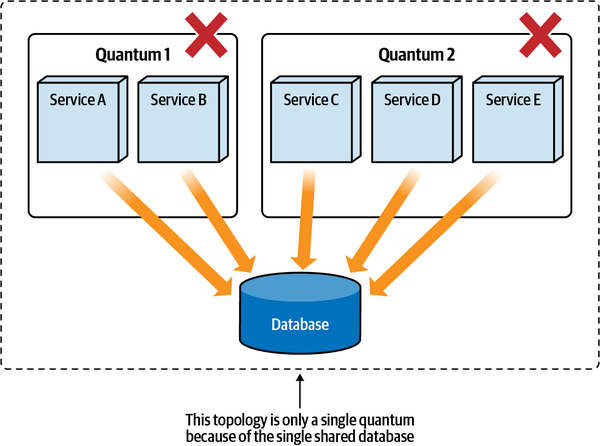

So far, the static coupling measurement of architecture quantum has evaluated all the topologies to one. However, distributed architectures create the possibility of multiple quanta but don’t necessarily guarantee it.

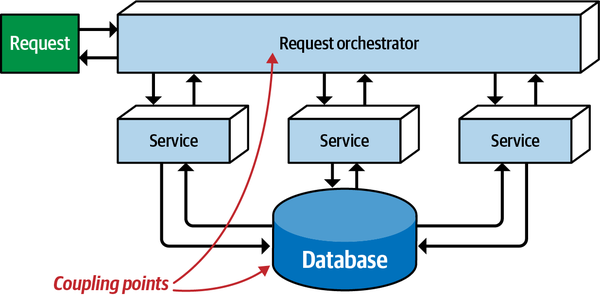

Even though this style represents a distributed architecture, two coupling points push it toward a single architecture quantum: the database, as common with the previous monolithic architectures, but also the Request Orchestrator itself—any holistic coupling point necessary for the architecture to function forms an architecture quantum around it.

Figure 2-4. A mediated EDA has a single architecture quantum

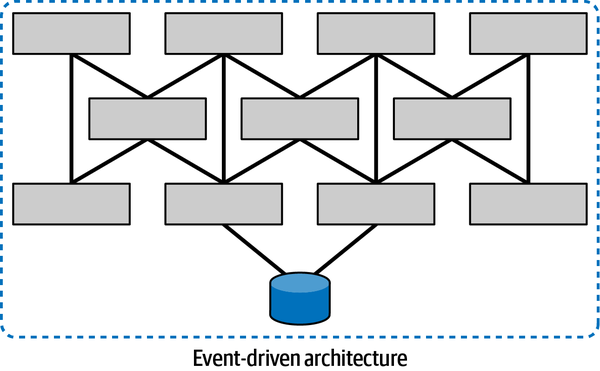

Broker event-driven architectures (without a central mediator) are less coupled,

This broker-style event driven architecture (without a central mediator) is nevertheless a single architecture quantum because all the services utilize a single relational database, which acts as a common coupling point. The question answered by the static analysis for an architecture quantum is, “Is this dependent of the architecture necessary to bootstrap this service?” Even in the case of an event-driven architecture where some of the services don’t access the database, if they rely on services that do access the database, then they become part of the static coupling of the architecture quantum.

Figure 2-5. Even a distributed architecture such as broker-style event-driven architecture can be a single quantum

However, what about situations in distributed architectures where common coupling points don’t exist?

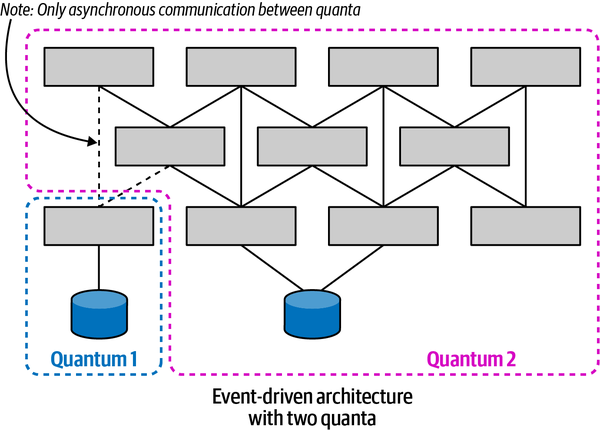

The architects designed this event-driven system

Figure 2-6. An event-driven architecture with multiple quanta

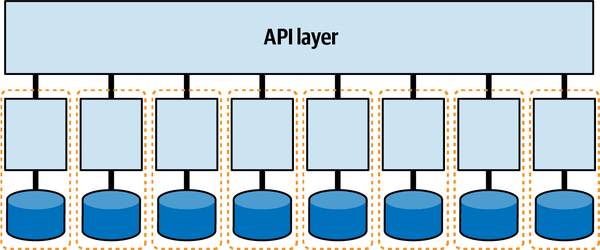

The microservices architecture style features

Figure 2-7. Microservices may form their own quanta

Each service (acting as a bounded context) may have its own set of architecture characteristics—one service might have higher levels of scalability or security than another. This granular level of architecture characteristics scoping represents one of the advantages of the microservices architecture style. High degrees of decoupling allow teams working on a service to move as quickly as possible, without worrying about breaking other dependencies.

However, if the system is tightly coupled to a user interface,

Figure 2-8. A tightly coupled user interface can reduce a microservices architecture quantum to one

User interfaces create coupling points between the front and back end, and most user interfaces won’t operate if portions of the backend aren’t available.

Additionally, it will be difficult for an architect to design different levels of operational architecture characteristics (performance, scale, elasticity, reliability, and so on) for each service if they all must cooperate together in a single user interface (particularly in the case of synchronous calls, covered in “Dynamic Quantum Coupling”).

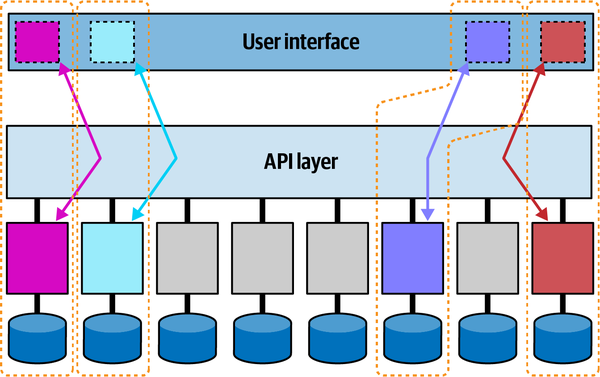

Architects design user interfaces utilizing asynchronicity that doesn’t create coupling between front and back. A trend on many microservices projects is to use a micro frontend framework for user interface elements in a microservices architecture. In such an architecture, the user interface elements that interact on behalf of the services are emitted from the services themselves. The user interface surface acts as a canvas where the user interface elements can appear, and also facilitates loosely coupled communication between components, typically using events. Such an architecture is illustrated in Figure 2-9.

Figure 2-9. In a micro-frontend architecture, each service + user interface component forms an architecture quantum

In this example, the four tinted services along with their corresponding micro-frontends form architecture quanta: each of these services may have different architecture characteristics.

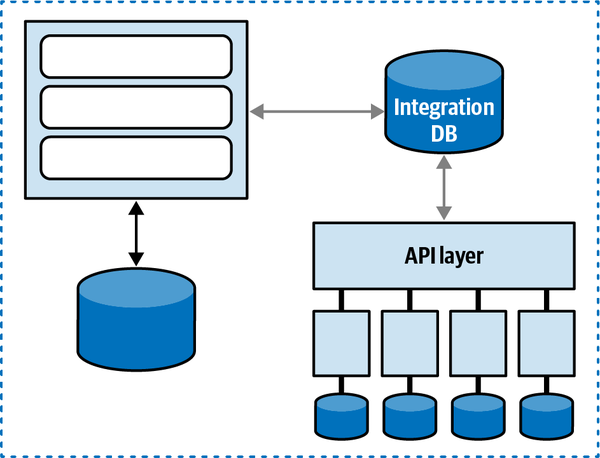

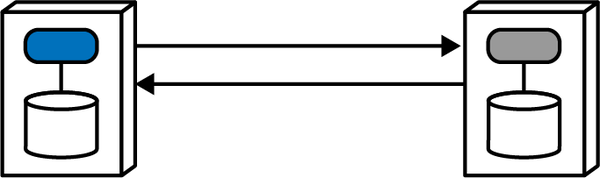

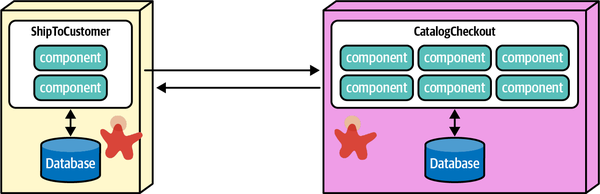

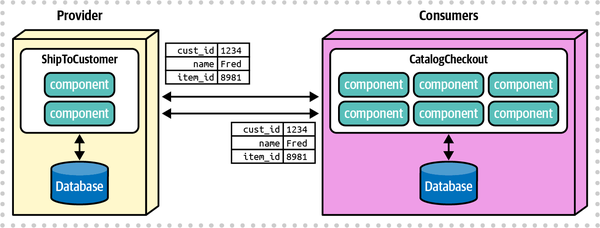

Any coupling point in an architecture can create static coupling points from a quantum standpoint. Consider the impact of a shared database between two systems, as illustrated in Figure 2-10.

The static coupling of a system provides valuable insight, even in complex systems involving integration architecture. Increasingly, a common architect technique for understanding legacy architecture involves creating a static quantum diagram of how things are “wired” together, which helps determine what systems will be impacted by change and offers a way of understanding (and potentially decoupling) the architecture.

Static coupling is only one-half of the forces at play in distributed architectures. The other is dynamic coupling.

Figure 2-10. A shared database forms a coupling point between two systems, creating a single quantum

Dynamic Quantum Coupling

The nature of how services call one another creates difficult trade-off decisions because it represents a multidimensional decision space, influenced by three interlocking forces:

- Communication

-

Refers to the type of connection synchronicity used: synchronous or asynchronous.

- Consistency

-

Describes whether the workflow communication requires atomicity or can utilize eventual consistency.

- Coordination

-

Describes whether the workflow utilizes an orchestrator or whether the services communicate via choreography.

Communication

Figure 2-11. A synchronous call waits for a result from the receiver

The calling service makes a call (using one of a number of protocols that support synchronous calls, such as gRPC) and blocks (does no further processing) until the receiver returns a value (or status indicating a state change or error condition).

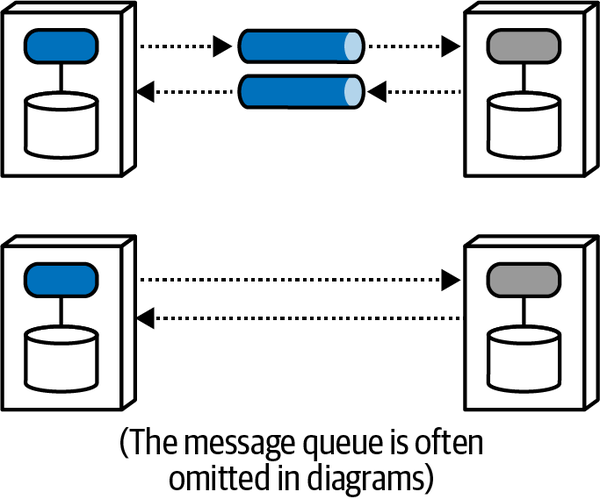

Asynchronous communication occurs between two services when the caller posts a message to the receiver (usually via a mechanism such as a message queue) and, once the caller gets acknowledgment that the message will be processed, it returns to work. If the request required a response value, the receiver can use a reply queue to (asynchronously) notify the caller of the result, which is illustrated in Figure 2-12.

Figure 2-12. Asynchronous communication allows parallel processing

The caller posts a message to a message queue and continues processing until notified by the receiver that the requested information is available via return call. Generally, architects use message queues (illustrated via the gray cylindrical tube in the top diagram in Figure 2-12) to implement asynchronous communication, but queues are common and create noise on diagrams, so many architects leave them off, as shown in the lower diagram. And, of course, architects can implement asynchronous communication without message queues by using a variety of libraries or frameworks. Each diagram variety implies asynchronous messaging; the second provides visual shorthand and less implementation detail.

Architects must consider significant trade-offs when choosing how services will communicate. Decisions around communication affect synchronization, error handling, transactionality, scalability, and performance. The remainder of this book delves into many of these issues.

Consistency

Consistency refers to the strictness of transactional integrity

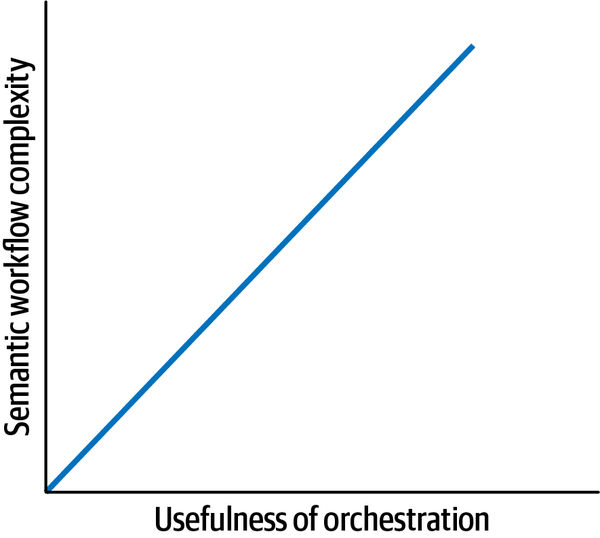

Coordination

Coordination refers to how much coordination the workflow

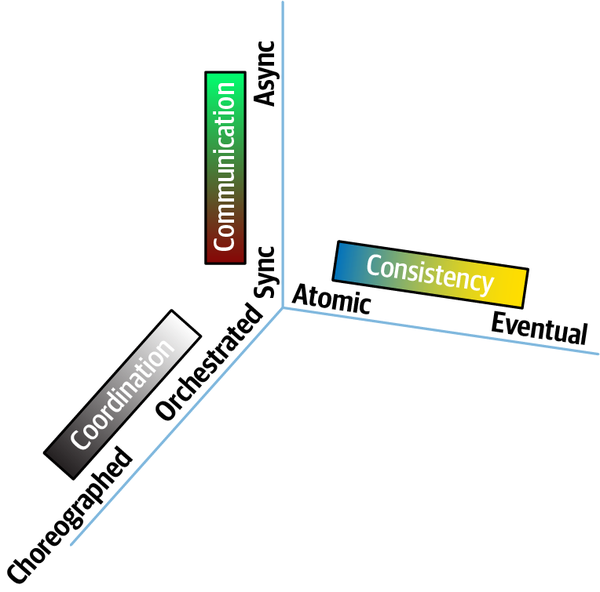

These three factors—communication, consistency, and coordination—all inform the important decision an architect must make. Critically, however, architects cannot make these choices in isolation; each option has a gravitation effect on the others. For example, transactionality is easier in synchronous architectures with mediation, whereas higher levels of scale are possible with eventually consistent asynchronous choreographed systems.

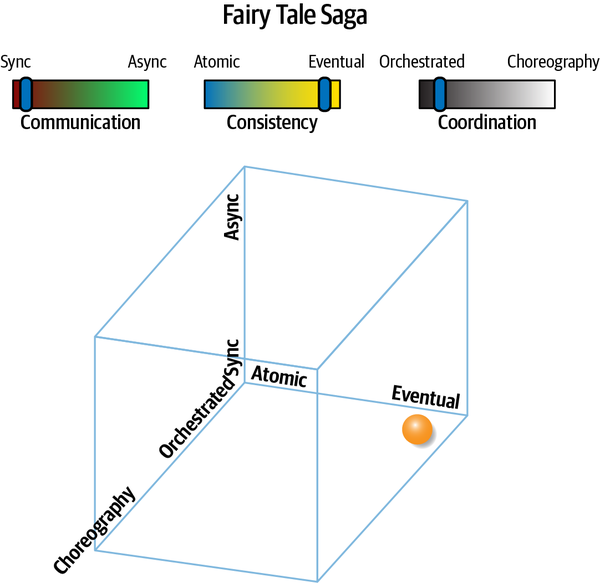

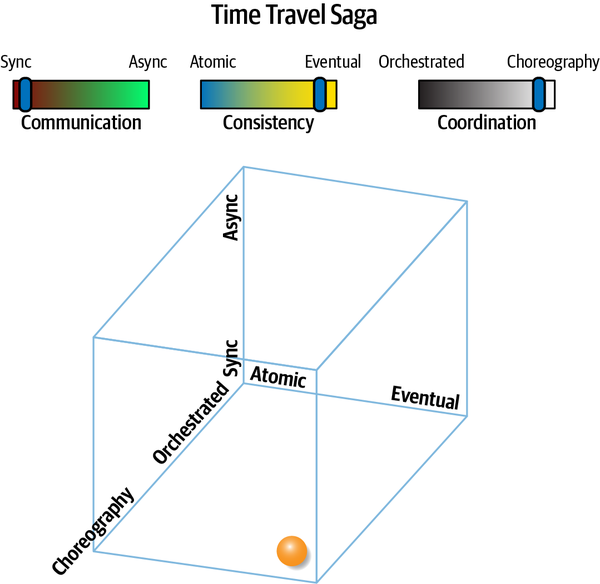

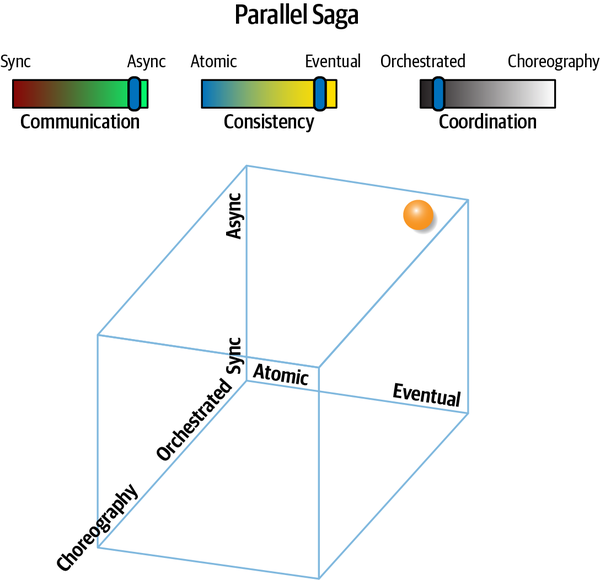

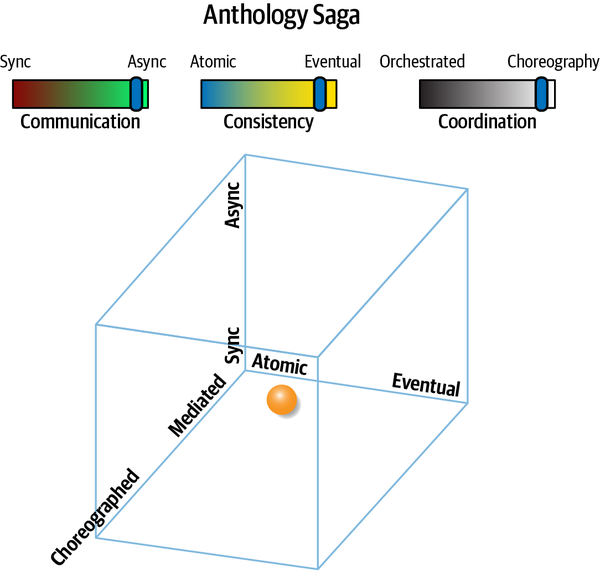

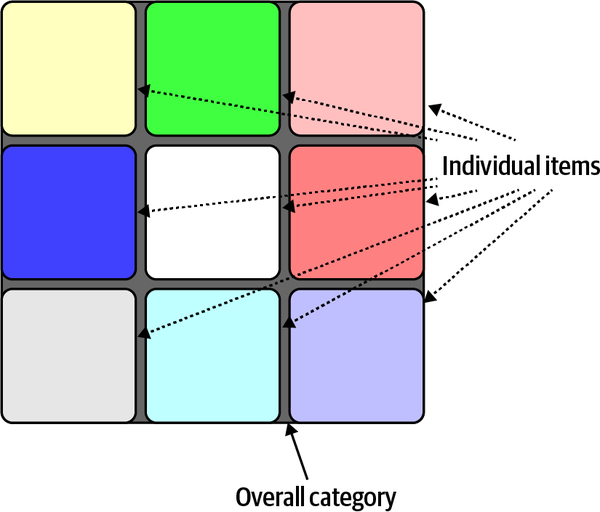

Thinking about these forces as related to each other forms a three-dimensional space, illustrated in

Each force in play during service communication appears as a dimension. For a particular decision, an architect could graph the position in space representing the strength of these forces.

Figure 2-13. The dimensions of dynamic quantum coupling

When an architect can build a clear understanding of forces at play within a given situation,

| Pattern name | Communication | Consistency | Coordination | Coupling |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Epic Saga(sao) | synchronous | atomic | orchestrated | very high |

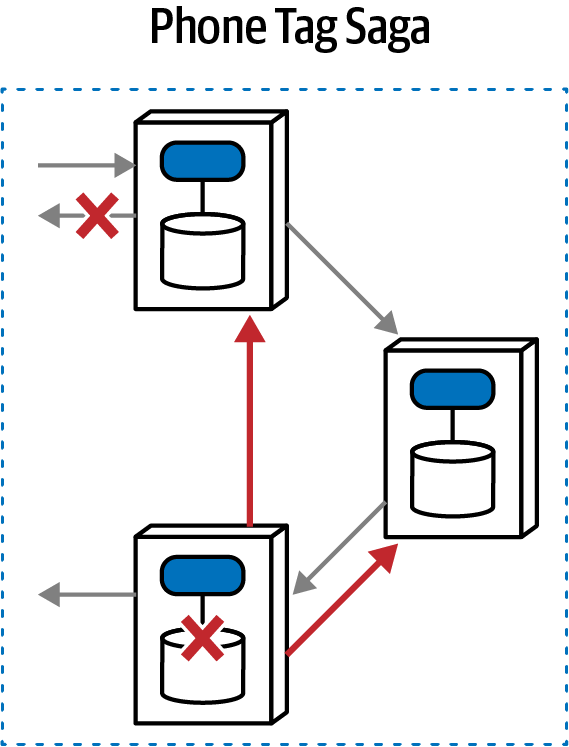

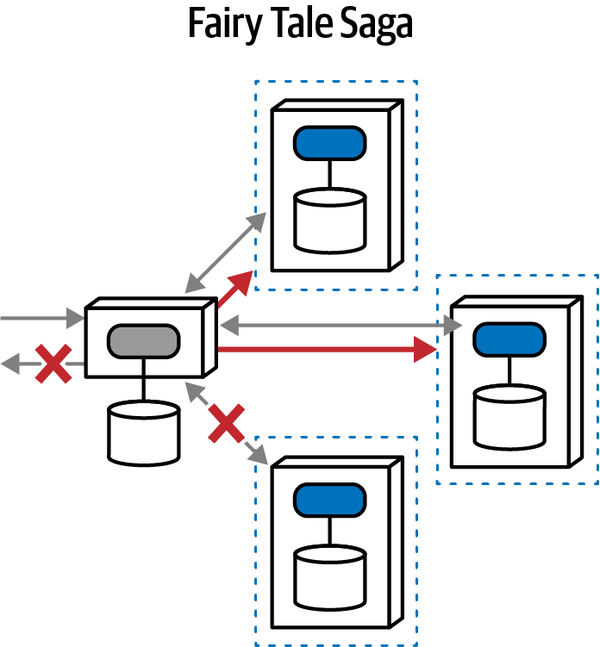

Phone Tag Saga(sac) | synchronous | atomic | choreographed | high |

Fairy Tale Saga(seo) | synchronous | eventual | orchestrated | high |

Time Travel Saga(sec) | synchronous | eventual | choreographed | medium |

Fantasy Fiction Saga(aao) | asynchronous | atomic | orchestrated | high |

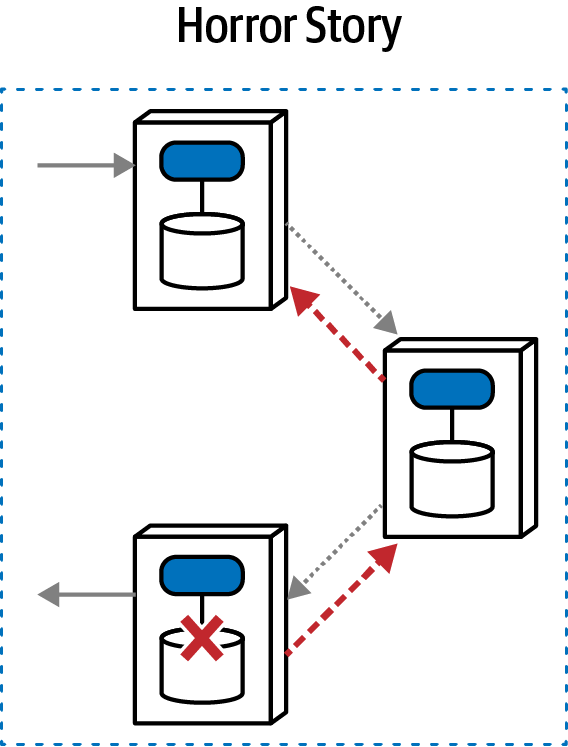

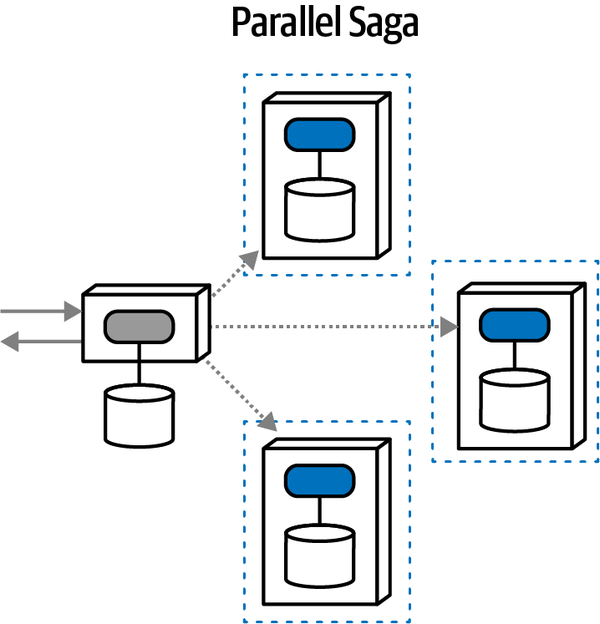

Horror Story(aac) | asynchronous | atomic | choreographed | medium |

Parallel Saga(aeo) | asynchronous | eventual | orchestrated | low |

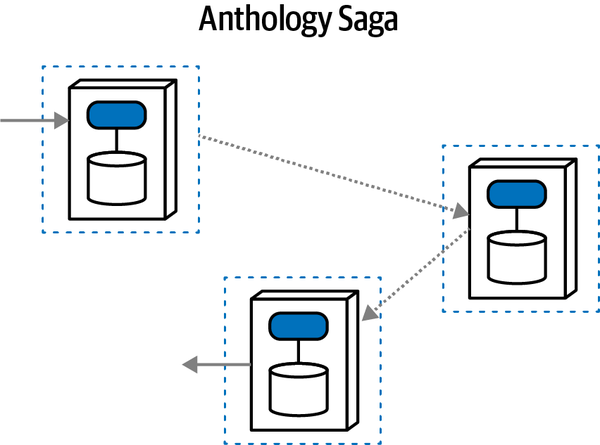

Anthology Saga(aec) | asynchronous | eventual | choreographed | very low |

To fully understand this matrix, we must first investigate each of the dimensions individually. Therefore, the following chapters help you build context to understand the individual trade-offs for communication, consistency, and coordination, then entangle them back together in Chapter 12.

Sysops Squad Saga: Understanding Quanta

Tuesday, November 23, 14:32

Austen came to Addison’s office wearing an uncharacteristic cross expression.

“Sure, what’s up?”

“I’ve been reading about this architecture quantum stuff, and I just…don’t…get…it!”

Addison laughed, “I know what you mean. I struggled with it when it was purely abstract, but when you ground it in practical things, it turns out to be a useful set of perspectives.”

“What do you mean?”

“Why not just use bounded context, then?” asked Austen.

“What is that all about? Isn’t coupling just coupling? Why make the distinction?”

“It turns out that a bunch of different concerns revolve around the different types,” said Addison. “Let’s take the static one first, which I like to think of as how things are wired together. Another way to think about it: consider one of the services we’re building in our target architecture. What is all the wiring required to bootstrap that service?”

“Well, it’s written in Java, using a Postgres database, and running in Docker—that’s it, right?”

“You’re missing a lot.” said Addison. “What if you had to build that service from scratch, assuming we had nothing in place? It’s Java, but also using SpringBoot and, what, about 15 or 20 different frameworks and libraries?”

“That’s right, we can look in the Maven POM file to figure out all those dependencies. What else?”

“But isn’t that the dynamic part?”

“Not the presence of the broker. If the service (or, more broadly, architecture quantum) I want to bootstrap utilizes a message broker to function, the broker must be present. When the service calls another service via the broker, we get into the dynamic side.”

“OK, that makes sense,” said Austen. “If I think about what it would take to bootstrap it from scratch, that’s the static quantum coupling.”

“That’s right. And just that information is super useful. We recently built a diagram of the static quantum coupling for each of our services defensively.”

Austen laughed. “Defensively? What do you…”

“We were performing a reliability analysis to determine if I change this thing, what might break, where thing could be anything in our architecture or operations. They’re trying to do risk mitigation—if we change a service, they want to know what must be tested.”

“I see—that’s the static quantum coupling. I can see how that’s a useful view. It also shows how teams might impact one another. That seems really useful. Is there a tool we can download that figures that out for us?”

“Wouldn’t that be nice!” laughed Addison. “Unfortunately, no one with our unique mix of architecture has built and open sourced exactly the tool we want. However, some of the platform team is working on a tool to automate it, necessarily customized to our architecture. They’re using the container manifests, POM files, NPM dependencies, and other dependency tools to build and maintain a list of build dependencies. We have also instituted observability for all our services, so we now have consistent log files about what systems call each other, when, and how often. They’re using that to build a call graph to see how things are connected.”

“OK, so static coupling is how things are wired together. What about dynamic coupling?”

“Oh, I see, I see! The architecture quantum defines the scope of architecture characteristics—it’s obvious how the static coupling can affect that. But I see now that, depending on the type of call you make, you might temporarily couple two services together.”

“That’s right,” said Addison. “The architecture quanta can entangle one another temporarily, during the course of a call, if the nature of the call ties things like performance, responsiveness, scale, and a bunch of others.”

“OK, I think I understand what an architecture quantum is, and how the coupling definitions work. But I’m never going to get that quantum/quanta thing straight!”

“Same for datum/data, but no one ever uses datum!” laughed Addison. “You’ll see a lot more of the impact of dynamic coupling on workflows and transactional sagas as you keep digging into our architecture.”

“I can’t wait!”

Chapter 3. Architectural Modularity

Tuesday, September 21 09:33

It was the same conference room they had been in a hundred times before, but today the atmosphere was different.

The business leaders and sponsors of the failing Sysops Squad ticketing application met with the application architects, Addison and Austen, with the purpose of voicing their concern and frustration about the inability of the IT department to fix the never-ending issues associated with the trouble ticket application. “Without a working application,” they had said, “we cannot possibly continue to support this business line.”

As the tense meeting ended, the business sponsors quietly filed out one by one, leaving Addison and Austen alone in the conference room.

“That was a bad meeting,” said Addison. “I can’t believe they’re actually blaming us for all the issues we’re currently facing with the trouble ticket application. This is a really bad situation.”

“Yeah, I know,” said Austen. “Especially the part about possibly closing down the product support business line. We’ll be assigned to other projects, or worse, maybe even let go. Although I’d rather be spending all of my time on the soccer field or on the slopes skiing in the winter, I really can’t afford to lose this job.”

“Neither can I,” said Addison. “Besides, I really like the development team we have in place, and I’d hate to see it broken up.”

“Me too,” said Austen. “I still think breaking apart the application would solve most of these issues.”

“I agree with you,” said Addison, “but how do we convince the business to spend more money and time to refactor the architecture? You saw how they complained in the meeting about the amount of money we’ve already spent applying patches here and there, only to create additional issues in the process.”

“You’re right,” Austen said. “They would never agree to an expensive and time-consuming architecture migration effort at this point.”

“But if we both agree that we need to break apart the application to keep it alive, how in the world are we going to convince the business and get the funding and time we need to completely restructure the Sysops Squad application?” asked Addison.

“Beats me,” said Austen. “Let’s see if Logan is available to discuss this problem with us.”

Addison looked online and saw that Logan, the lead architect for Penultimate Electronics, was available. Addison sent a message explaining that they wanted to break apart the existing monolithic application, but weren’t sure how to convince the business that this approach would work. Addison explained in the message that they were in a real bind and could use some advice. Logan agreed to meet with them and joined them in the conference room.

“What makes you so sure that breaking apart the Sysops Squad application will solve all of the issues?” asked Logan.

“Because,” said Austen, “we’ve tried patching the code over and over, and it doesn’t seem to be working. We still have way too many issues.”

“You’re completely missing my point,” said Logan. “Let me ask you the question a different way. What assurances do you have that breaking apart the system will accomplish anything more than just spending more money and wasting more valuable time?”

“Well,” said Austen, “actually, we don’t.”

“Then how do you know breaking apart the application is the right approach?” asked Logan.

“We already told you,” said Austen, “because nothing else we try seems to work!”

“Sorry,” said Logan, “but you know as well as I do that’s not a reasonable justification for the business. You’ll never get the funding you need with that kind of reason.”

“So, what would be a good business justification?” asked Addison. “How do we sell this approach to the business and get the additional funding approved?”

“Well,” said Logan, “to build a good business case for something of this magnitude, you first need to understand the benefits of architectural modularity, match those benefits to the issues you are facing with the current system, and finally analyze and document the trade-offs involved with breaking apart the application.”

It’s difficult in today’s world to manage all of this constant and rapid change with respect to software architecture. Software architecture is the foundational structure of a system, and is therefore generally thought of as something that should remain stable and not undergo frequent change, similar to the underlying structural aspects of a large building or skyscraper. However, unlike the structural architecture of a building, software architecture must constantly change and adapt to meet the new demands of today’s business and technology environment.

Figure 3-1. A full glass representing a large monolithic application close to capacity

One aspect of architectural modularity is

Figure 3-2. Two half-full glasses representing an application broken apart with plenty of capacity for growth

Increased scalability is only one benefit of architectural modularity.

There is one thing that will separate the pack into winners and losers: the on-demand capability to make bold and decisive course-corrections that are executed effectively and with urgency.

Businesses must be agile in order to survive in today’s world. However, while business stakeholders may be able to make quick decisions and change direction quickly, the company’s technology staff may not be able to implement those new directives fast enough to make a difference. Enabling technology to move as fast as the business (or, conversely, preventing technology from slowing the business) requires a certain level of architectural agility.

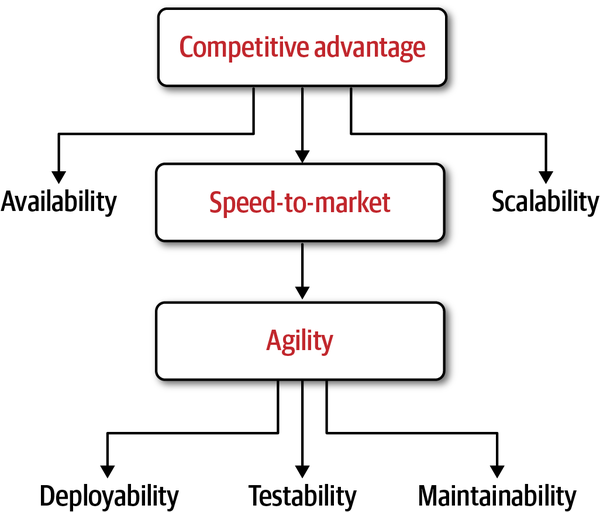

Modularity Drivers

Businesses must be agile to survive in today’s fast-paced and ever-changing

Figure 3-3. The drivers for modularity and the relationships among them

Note that architectural modularity does not always have to

Maintainability

Maintainability is about the ease of adding, changing, or removing features,

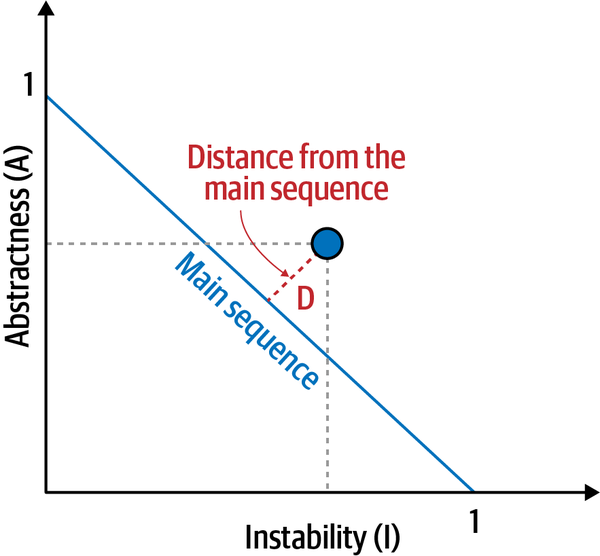

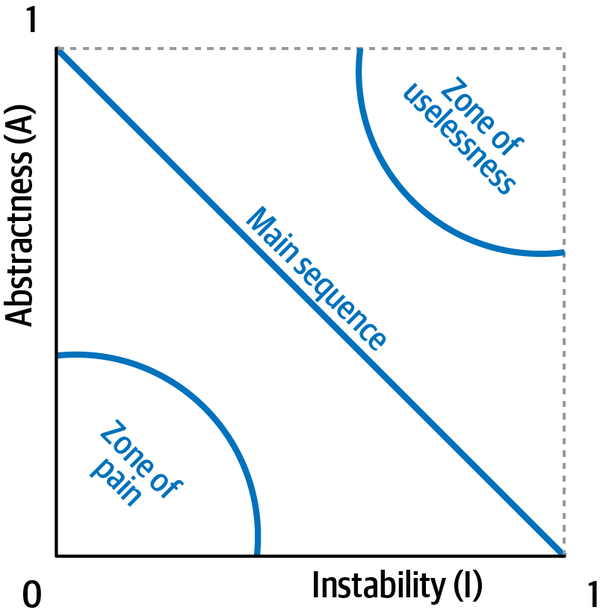

where ML is the maintainability level of the overall system (percentage from 0% to 100%), k is the total number of logical components in the system, and ci is the coupling level for any given component, with a special focus on incoming coupling levels. This equation basically demonstrates that the higher the incoming coupling level between components, the lower the overall maintainability level of the codebase.

Putting aside complicated mathematics, some of the typical metrics used for determining the relative maintainability of an application based on components (the architectural building blocks of an application) include the following:

- Component coupling

-

The degree and manner to which components know about one another

- Component cohesion

- The degree and manner to which the operations of a component interrelate

- Cyclomatic complexity

- The overall level of indirection and nesting within a component

- Component size

-

The number of aggregated statements of code within a component

- Technical versus domain partitioning

- Components aligned by technical usage or by domainpurpose—seeAppendix A

Within the context of architecture, we are

app.business.order.history.

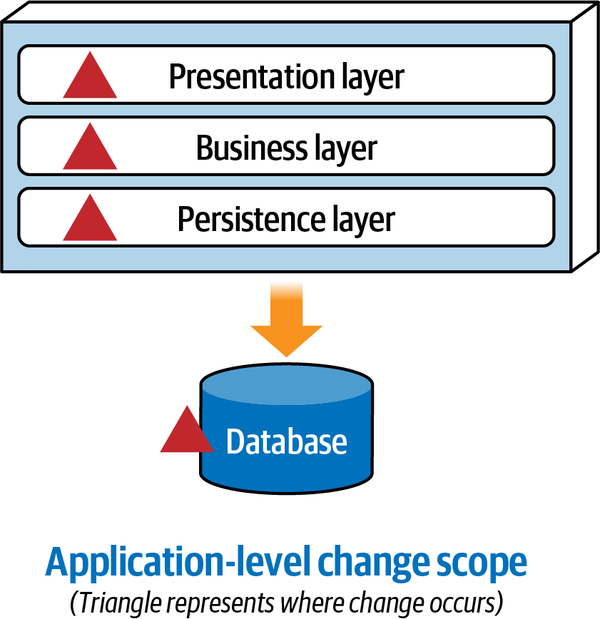

Figure 3-4. With monolithic layered architectures, change is at an application level

Depending on the team structure, implementing this simple change to add an expiration date to wish list items in a monolithic layered architecture could possibly require the coordination of at least three teams:

-

A member from the user interface team would be needed to add the new expiry field to the screen.

-

A member from the backend team would be needed to add business rules associated with the expiry date and change contracts to add the new expiry field.

-

A member from the database team would be needed to change the table schema to add the new expiry column in the Wishlist table.

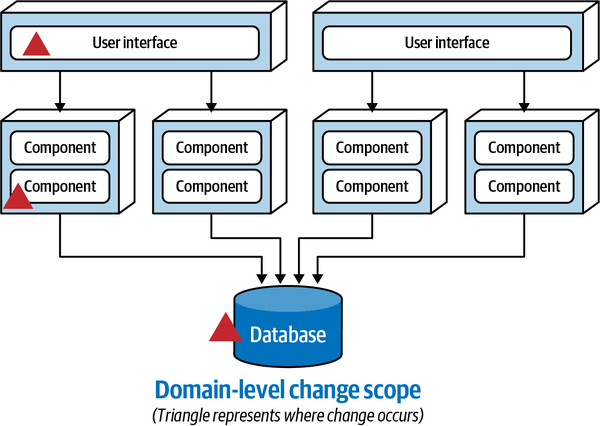

Since the Wishlist domain is spread throughout the entire architecture, it becomes harder to maintain a particular domain or subdomain (such as Wishlist). Modular architectures, on the other hand, partition domains and subdomains into smaller, separately deployed units of software, thereby making it easier to modify a domain or subdomain. Notice that with a distributed service-based architecture, as shown in Figure 3-5, the change scope of the new requirement is at a domain level within a particular domain service, making it easier to isolate the specific deployment unit requiring the change.

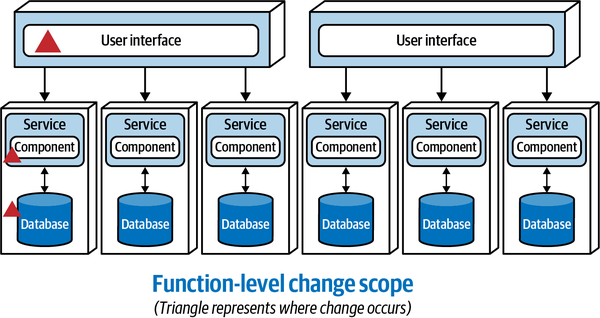

Moving to even more architectural modularity

Figure 3-5. With service-based architectures, change is at a domain level

Figure 3-6. With microservices architectures, change is at a function level

These three progressions toward modularity demonstrate that as the level of architectural modularity increases, so does maintainability, making it easier to add, change, or remove functionality.

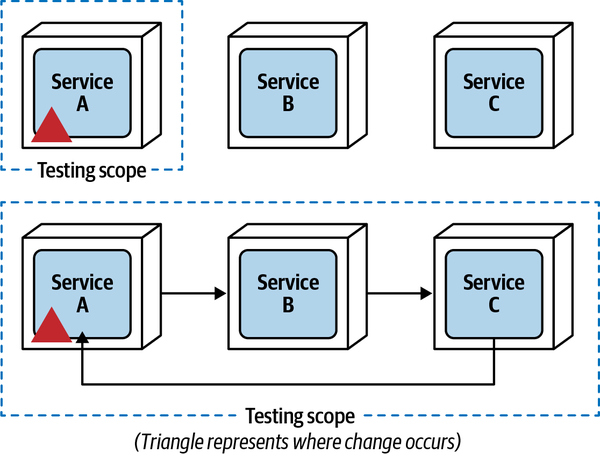

Testability

Making a change to Service A limits the testing scope to only that service, since Service B and Service C are not coupled to Service A. However, as communication increases among these services, as shown at the bottom of Figure 3-7, testability declines rapidly because the testing scope for a change to Service A now includes Service B and Service C, therefore impacting both the ease of testing and the completeness of testing.

Figure 3-7. Testing scope is increased as services communicate with one another

Deployability

Deployability is not only about the ease of deployment—it is also about

If your microservices must be deployed as a complete set in a specific order, please put them back in a monolith and save yourself some pain.

This scenario leads to what is commonly referred to as the “big ball of distributed mud,” where very few (if any) of the benefits of architectural modularity are realized.

Scalability

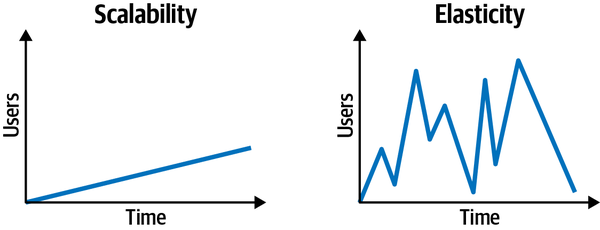

Scalability is defined as the ability of a system to remain

Figure 3-8. Scalability is different from elasticity

While both of these architectural characteristics include responsiveness as a function of the number of concurrent requests (or users in the system), they are handled differently from an architectural and implementation standpoint. Scalability generally occurs over a longer period of time as a function of normal company growth, whereas elasticity is the immediate response to a spike in user load.

A great example to further illustrate the difference is that of a concert-ticketing system. Between major concert events, there is usually a fairly light concurrent user load. However, the minute tickets go on sale for a popular concert, concurrent user load significantly spikes. The system may go from 20 concurrent users to 3,000 concurrent users in a matter of seconds. To maintain responsiveness, the system must have the capacity to handle the high peaks in user load, and also have the ability to instantaneously start up additional services to handle the spike in traffic.

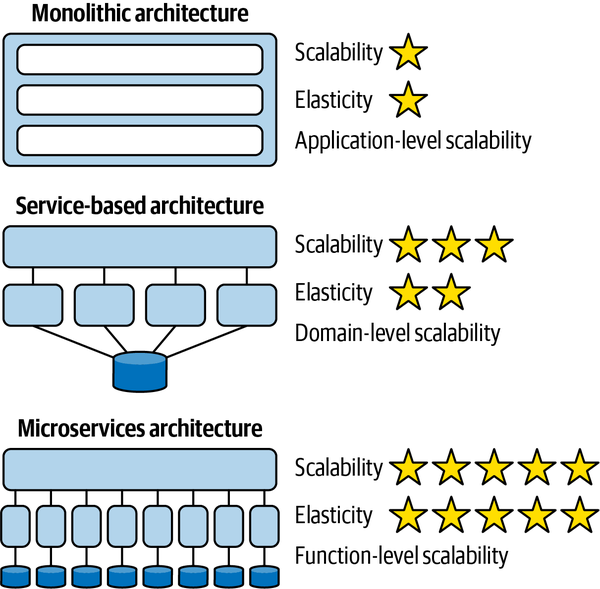

Notice that scalability and elasticity rate relatively low with the monolithic layered architecture. Large monolithic layered architectures are both difficult and expensive to scale because all of the application functionality must scale to the same degree (application-level scalability and poor MTTS). This can become particularly costly in cloud-based infrastructures.

Figure 3-9. Scalability and elasticity improve with modularity

Availability/Fault Tolerance